Time to get serious about security

For power plants, the unintended consequence of “going digital” is dealing with cyber security. Almost everything that makes today’s distributed control systems (DCSs) and software so powerful, convenient, and cost-effective also makes them vulnerable to cyber attacks.

For years, the plants themselves were less vulnerable to such attacks than corporate institutions or the public at large because DCSs relied on proprietary protocols. But those systems were pried open to make them more interoperable, remotely accessible, and less costly. Now they use open software standards and protocols.

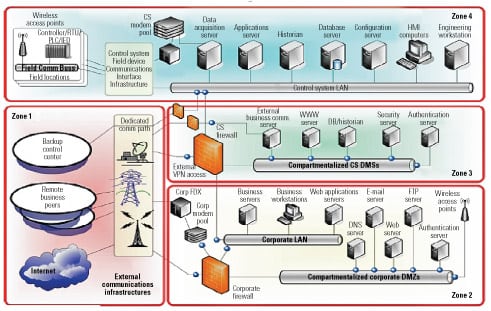

The opening up of plant systems has blurred the distinction between them and corporate information systems. Watching a plant engineer use a cell phone or PDA to call up a plant’s performance data and real-time operating parameters drives home the point. The “lines of communication” are now many and varied (see figure) and therefore vulnerable to intruders.

In the zone. Cyber security experts recommend dividing up the “meta organization” into zones requiring different protection schemes. Source: Trent Nelson, “Cyber Security—Who Needs It?” Idaho National Laboratory, Department of Homeland Security (April 18, 2007)

Crazy cyber quilt

Most plants manage cyber security by making a seemingly endless series of patches and security updates to their control and information systems. However, few plants have the resources to track the rise of viruses, worms, and other threats targeting them. Some plants rely on automated services provided by their DCS or software vendor. That’s convenient, but it also creates additional lines of vulnerability. Another level of complexity is introduced by the many DCS operating requirements that do not support the type of security models used by the rest of the IT industry.

The future, unfortunately, is even more complicated. New cyber security standards for critical infrastructure protection (CIP) that were approved in January by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) have changed the landscape. In short, the new standards (and other business drivers) will force plants to be proactive, rather than reactive, in their approaches to cyber security.

Asset managers seeking to counter the cyber security threat face a multifaceted challenge:

- The realm of plant automation and control is clashing head-on with that of corporate IT (see table). Digital systems may advance rapidly, but they become obsolete just as quickly. Each new technology paradigm, such as the “smart grid,” potentially adds another level of vulnerability.

- Many plant staffs have already been pared to the bone. Site expertise in cyber issues is rare to nonexistent.

- The new CIP standards (see sidebar, "New CIP standards leave much discretion to plant owners/operators")—which were developed by the North American Electric Reliability Corp. (NERC), FERC’s designated national electrical reliability organization—are ambiguous at best and arguably not even standards at worst. FERC’s authority to implement and enforce mandatory reliability standards is being challenged by many lawsuits. (For a listing and summaries of the cases, go to www.ferc.gov/legal/court-cases/pend-case.asp.) The suits don’t lessen the need for CIP projects, even if those suits take years to settle.

- Corporate owners have to meet other obligations, such as “public disclosure in the event of revenue flow disruption as a result of a cyber incident.” That’s the word from “Effective Practices for Securing Distributed Control Systems in Power Generation Facilities,” a white paper published by Symantec Enterprise Solutions and downloadable from https://www4.symantec.com/Vrt/offer?a_id=20174.

- Many plants today are linked, through wired or wireless connections, to centralized performance-monitoring facilities, employees responsible for multiple sites, mobile plant employees, corporate staff, vendors providing outsourced services, and even government agencies that monitor stack emissions. This so-called “meta organization” offers multiple points of vulnerability exploitable by miscreants.

- Plant assets include DCS or control systems of varying vintages, versions, and variations, depending on past modifications at the plant level.

IT systems and plant distributed control systems (DCS) treat aspects of cyber security very differently. Source: Trent Nelson, “Cyber Security—Who Needs It?” Idaho National Laboratory, Department of Homeland Security (April 18, 2007)

Beyond CIP compliance

Although space constraints preclude a deep discussion of the details, the new CIP standards cover the following areas: critical cyber-security asset identification, security management controls, personnel and training, electronic security perimeters, physical security of critical cyber assets, systems security management, incident reporting and response planning, and recovery plans for critical cyber assets. The full texts of the standards are available at www.nerc.com.

Most governmental and quasi-governmental standards become the equivalent of the minimum daily requirement for nutrition. That is, they set the floor, not the ceiling, for compliance. However, for the purposes of actually protecting your revenue-producing assets, you need to think beyond these standards. Security experts note that many of the vulnerability scenarios are not well-understood.

For example, suppose someone secretly installed viruses or worms on DCS systems at multiple plants and synchronized their activation so controls or equipment would be disabled at a specific time in the future. Think of these lines of code as errant Y2K-like tickers lurking in multiple systems. Suddenly, an asset that wouldn’t be considered “critical” becomes critical because it is linked with other assets that would be crippled at the same time. This is the kind of scenario that keeps cyber security experts up at night. Last fall, a video marked “Official Use Only” was obtained by the Associated Press. Thought to have been produced by The Department of Homeland Security and Idaho National Laboratory, it shows an industrial turbine spinning out of control and being destroyed after having been commandeered by hackers in a mock attack.

Another way for plants to approach the new cyber security regime is to “think like a nuke.” Conceptually, managing threats and vulnerabilities, whether physical or cyber, involves the same methodologies. Nuclear plants have decades of experience in this area that could be tapped to improve the security of the U.S. fossil-fueled fleet.

Eventually, the NERC standards may get everyone on the same page. In the meantime, plants need to find some middle path between conducting business as usual and trying to meet the letter of a treaty that hasn’t yet been ratified. Some suggested actions for plant managers to take while the industry waits for more specific instructions from regulatory agencies—or the courts—follow.

Appoint someone to manage or be responsible for cyber security. CIP is no longer something that can be outsourced, treated as a DCS vendor service, or tossed over to corporate. The “responsible entity” (FERC’s jargon) must be given the resources and the budget to get the job done.

Think of cyber security as another function. Treat it as you would environmental health and safety (EHS). Almost every plant has an EHS department or an EHS coordinator. The same should be true for cyber security. At the very least, someone needs to follow what happens to the NERC standards as they wind their way through the legal challenges.

Conduct a security assessment of all of your digital systems and equipment. Also make sure you have the latest cyber security expertise on your team. That could be accomplished in conjunction with a configuration management (CM) program to identify and bridge gaps between the DCS or plant computer and the myriad software and performance applications and communications gateways.

The problem is, many DCS systems either lack a CM tool, or what they provide is incompatible with other constraints facing the plant. CM is the control system equivalent of having updated engineering drawings of physical equipment, as opposed to “as-built” drawings of the original plant design. For most plants, cyber security represents a new functional requirement that wasn’t there when the plant was designed. Note that CM is absolutely essential at nuclear plants, which have used it for years.

Begin to develop a set of written (or documented) policies and procedures to address cyber security issues. It is no longer enough to do things ad hoc or to rely on word of mouth.

—Timothy E. Hurst, PE ([email protected]) is president of Hurst Technologies (www.hcinc.com), a consulting engineering firm specializing in instrumentation and control systems for nuclear and fossil-fueled power stations. He also is a POWER contributing editor.