Which Side of the Meter Are You On?

Utilities have achieved success by supplying electricity from central station plants (the supply side) to a grid that carries electricity to customers (the demand side). One way to improve the efficiency of this supply chain is by adopting smart grid technology. The weak link in that chain is convincing customers to use, and regulators to invest in, the smart grid.

Is the electric meter turning out to be the great divide for the utility industry?

On the upstream side, utility executives extol the efficiencies and overall benefits that a smart grid brings to their operations. Downstream, they talk about getting closer to their customers, even though they’re still not sure what their customers want. Customers have not exactly reciprocated in a warm and fuzzy way to let them know—if, indeed, the customers know themselves.

While smart grid programs and technology continue to evolve, different utilities may pursue differing visions for their smart grid programs. Diverse strategies and implementation flavors will emerge from each utility’s particular situation. A more standardized set of smart grid solutions will no doubt gain acceptance over time, as the set of technologies progresses along its maturation curve.

The chief executive officers of some of the largest U.S. utilities, during a panel discussion at the Edison Electric Institute (EEI) meeting last June, spoke highly of the tangible value that smart meters and smart grid initiatives have brought to their companies.

One CEO flat-out said, “Our smart meters pay for themselves.” He pointed out that the company saves on the cost of meter reading, gets an early jump on energy theft schemes, and, because his service area has a large transient customer base, the utility saves a lot of money on service connects and disconnects.

Other executives had the same view; one said that “Operational benefits can justify the system without even looking at the customer side of the meter,” while another, whose company has a major smart grid installation in one city in its service territory, acknowledged that the major benefits that he has seen so far are on the company side (that is, “upstream”) of the meter.

A presentation by Black & Veatch to Wall Street utility analysts in August articulated a similar line of thought, citing a dozen or so benefits that the smart grid can bring to utilities in terms of operations and maintenance, capital expenditures, and revenue, including these:

- Improved forecast processes for power purchasing.

- Improved transformer load management.

- Assistance in rate design.

- Reduced time for resolving billing issues with customers.

- More efficient management of service outages.

- Integration of renewable energy resources (which are either intermittent or highly variable, depending on your point of view).

- Elimination of manual meter reading expenses.

- Faster detection of theft.

Yet, despite these widely acknowledged advantages that yield significant cost savings and have the long-term potential to provide customers with better reliability as the systems evolve, one of the EEI panelists fretted that if his utility did not penetrate the market downstream of the meter to the retail customer level, it could be relegated to being “just a commodity provider” while losing opportunities for new markets to the likes of Microsoft and Google.

This, in turn, generates the question, What is wrong with being the provider of an absolutely essential, ubiquitous commodity if you can do it efficiently and reliably; constrain customer rates; provide thousands of local, high-quality jobs; enable other market services; and provide low-risk returns to shareholders? Beyond-the-meter opportunities may generally be a poor fit for utilities. And, after all, the No. 1 priority for any utility is keeping the lights on, as Exelon CEO John Rowe reminded everyone at the EEI meeting.

Should Utilities Be in the Home Energy Management Business?

Do customers want utility involvement down to the electricity usage level? Do customers even care about being able to finely slice their energy usage? Are utilities better off leaving the day-to-day data management to household-name technology and service providers? And is home energy management such a small part of the future home area network that it does not or should not matter?

The high-tech companies seem to be positioning themselves to achieve large shares of the behind-the-meter technology market by way of smart in-home systems and customer/utility interfaces. To avoid compromising core capabilities, utilities will most likely need to partner with such companies to help improve customer satisfaction and reliability, reduce costs, minimize risk, and increase cash flow, Len Rodman, Black & Veatch CEO, said at the RMEL conference in September. In other words, Rodman said, it’s not a matter of competing with the likes of Google, but rather determining how to team up with these new entrants to deliver higher levels of customer service and reliability, without assuming risks out of proportion to normal utility returns.

Many utilities have little, if any, competitive advantage in these markets—nor should they. Electric utilities didn’t compete, for example, with General Electric when it introduced its full range of then-high-tech home electric appliances in the 1940s and 1950s, or with Carrier and Trane for a share of the air conditioning market. The power industry simply wanted to increase energy sales. Similarly, why should its core business model imply a need to compete with Google and other vendors of behind-the-meter products and services?

Exelon’s Commonwealth Edison unit provides a telling example. Its pilot smart meter project, involving 131,000 randomly selected customers, found that only about 8% of those chosen actually activated their online accounts enabling them to view their usage on a website, a company executive said at the fall 2010 GridWeek conference. The company later noted, though, that the communications program to inform customers about the pilot did not fully get off the ground before the Appellate Court of Illinois nixed the cost-recovery mechanism. A new cost-recovery plan was filed with state utility regulators in October. Before the project was put on hold, the utility had started a smaller pilot in which 5,000 customers were randomly assigned one of several dynamic pricing plans and offered feedback devices for installation in their homes. Customers could opt out; 1,100 (22%) chose to participate.

Many Downstream Benefits of a Smart Grid

A well-executed smart grid project could have beyond-the-meter downstream benefits, to be sure, such as sophisticated pricing schemes to help shift customer loads and trim load during peak periods. Many utilities have used some form of demand management for years that allows them, for example, to shut off residential central air conditioning units for brief periods on critical peak days in return for a discount on the customer’s bill, which applies even if the utility never has to exercise its shutoff option. Downstream smart systems would allow the utility to go further, possibly restricting the use of other household appliances at critical times and collecting data pertaining to patterns of usage.

Utilities should think about whether they even want to go down that road. A host of questions, still largely unanswered, pertain to areas that could expose utilities to liability and business challenges that they have not had to deal with before:

- Who owns the data collected from a customer’s home?

- How intrusive will the data collection be, and how can confidentiality be managed?

- What are the liabilities in cases of misused data or identity theft?

- Will this increase the utility’s exposure to potential breaches in cybersecurity?

In his speech to the RMEL conference, Black & Veatch CEO Rodman said that “by continuing to focus on doing… traditional jobs exceptionally well and doing some routine processes in a more innovative way, you can navigate the rough waters to assure least-cost operations, to attract capital and to deliver an industry infrastructure that is strong and reliable.”

Executives should also consider whether making a deep and costly commitment on the customer side of the market might distract them from resolving the following issues that are critical in the long term to keeping the lights on (see sidebar):

- The push from federal and state governments for substantial reductions in power plant emissions of carbon dioxide.

- The development of economical energy storage, which will be important for the large-scale viability of renewables.

- The added strains on the power distribution network that could come from rapid growth of plug-in electric cars.

- Changing fuel market dynamics brought about by significant new, prolific natural gas discoveries.

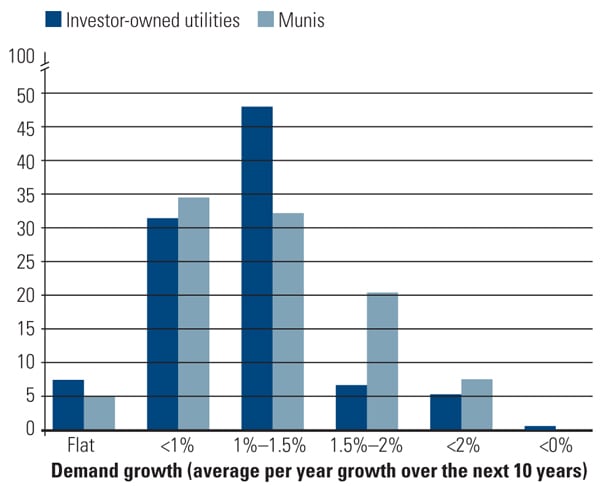

- Uncertain post-recession demand trends for electricity.

Senior management must make major decisions to resolve these basic infrastructure issues before shifting attention to the customer side of the meter. And they do not have a lot of time to figure it out. For the vertically integrated utility, a decision on investing tens of millions of dollars for environmental retrofits at older coal-fired plants or retiring smaller units and replacing that capacity needs to be resolved before jumping with both feet into the home energy management business.

Developing New Relationships with All Stakeholders

How does all this get sorted out in the battle for the hearts and minds of customers, who do need to be cognizant of the way they use energy? Customer benefits downstream of the meter will likely require a new energy services company business model—one that is nonregulated, for profit, and likely to be utility-affiliated. That new energy services company might provide a menu of services relating to conservation, possibly competitive purchasing, and perhaps management of the demand-responsive pricing programs that are coming.

At the same time, however, utilities that want to build a business on the customer side of the meter, whether in partnership or alone, need to realize that the risk profile is significantly different on the downstream side.

For now, though, customers generally don’t think twice about the juice coming from the wall socket. To put it another way, “people don’t desire electricity—they desire the services of the devices,” Carnegie Mellon University economics and engineering Professor Lester Lave told the Carnegie Mellon Conference on the Electricity Industry in March 2010.

Because utilities provide such a critical product, those closest to the mission often think that everyone else also knows its importance, although an ongoing education plan to remind legislators, regulators, and the public at large might not be a bad thing.

Major issues of environmental regulations, fuel supply, and renewable generating technology are facing the utility industry. The way they are addressed will be increasingly critical to maintaining reliable service at a reasonable price. That’s a lot on any manager’s plate. The smart grid has proven benefits on the supply side, and as desirable as it may be to cross through the meter and get close to those who are paying the bill each month, it might be a better use of time, and more cost-effective, to partner with a company that has the expertise, reputation, and market exposure in dealing with customers at the household level.

Years ago, an anti-nuclear activist told a newspaper reporter that the cost of a proposed nuclear plant represented a very expensive way to make toast. It was a glib remark that made good fodder for the popular press. It also missed the point (probably intentionally) that a reliable power supply is of paramount societal importance and cannot be taken for granted. The availability of electricity is never given a second thought—until the lights go out.

— William J. Kemp ([email protected]) is associate vice president for strategy & sustainability services at Black & Veatch Management Consulting. Andrew Trump ([email protected]) is an executive consultant with Enspiria Solutions, a Black & Veatch Company.