Waste-to-Energy Strategies Are Not Dead

Few waste-to-energy (WTE) plants have been completed in the U.S. since the mid 1990s, but the story is different around the world, where WTE technology is seen as a suitable solution to municipal solid waste management challenges. New processes, such as landfill gas collection, could find support everywhere as they provide a more environmentally friendly way to reduce methane emissions.

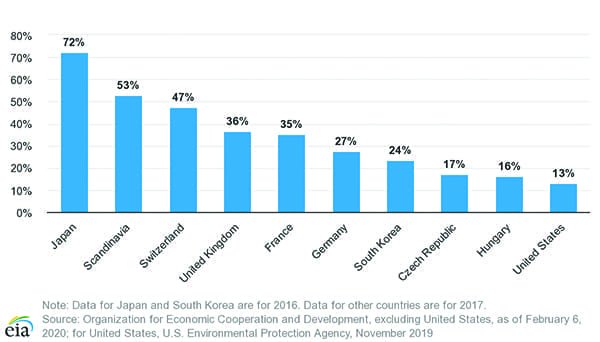

Do you know what happens to garbage after you throw it away? If you’re in a community with a waste-to-energy (WTE) plant, it may be powering your lights. According to the Energy Information Administration’s (EIA’s) Monthly Electric Generator Inventory report from February 2020, there were 83 WTE plants in the U.S. with a total nameplate capacity of more than 2,553 MW. Yet, only about 13% of the municipal solid waste (MSW) generated in the U.S. is burned in WTE plants, according to the EIA.

A World of Opportunity

However, WTE facilities are more popular in other parts of the world. ResearchAndMarkets.com in a March 2020-released report said it expects the world’s WTE market to grow at a compound annual growth rate of about 6.45% through 2025. It claims growing urban populations in the Asia-Pacific region, greater industrialization, and an increase in economic development are driving a surge in MSW. It says the effective disposal of MSW has become a serious environmental challenge in some parts of Asia, and suggests thermal-based WTE plants offer a viable solution to the problem. Meanwhile, countries in Europe and the Middle East are also adding WTE plants to their power mixes.

Japan. Japan leads the world in the percentage of its waste utilized in WTE facilities, burning 72% of its MSW in energy recovery systems (Figure 1). The country has focused on WTE technology since as early as the 1960s. One reason the WTE industry has thrived in Japan is because the country has little room for landfills and burning waste has been considered a better solution.

According to a United Press International (UPI) article published last year, Japan operates more than 380 WTE plants domestically. Now, Japan is looking to export its WTE expertise to other countries. UPI reported that Japan is pursuing agreements to construct WTE plants in Vietnam, Indonesia, and the Philippines. Thailand was also mentioned as a prime target because it has been dumping garbage in the ocean. “Tokyo’s goal is to conclude technical agreements with 10 ‘regions’ and build waste-to-energy plants in the region,” the article says.

Israel. The Times of Israel reported in May that three WTE plants had been greenlighted in central Israel as part of the Environment Ministry’s plan to reduce the amount of waste going to landfills. One of the proposed sites is southeast of Tel Aviv, another is in the northern industrial zone of Ashdod, and the third is east of Jerusalem. Israel’s “Strategic Plan for the Treatment of Waste by 2030” targets recycling 51% of its waste, treating another 23% at WTE plants, and sending 26% to landfill, compared to about 80% that ends up in landfill today.

Russia. A new WTE plant designed to process 720,000 tons of MSW per year is being constructed near Moscow (Figure 2). It is expected to be the first of four plants to be built in the region in coming years. Hitachi Zosen Inova AG is the engineering, procurement, and construction contractor for the project, which will have a thermal capacity of 227.5 MW and an electrical capacity of 75 MW. In May, Valmet announced that it would supply its DNA automation system and an information management system to control the new plant’s boiler and balance of plant. The facility will be owned and operated by Alternative Generating Company-1 (AGC-1) and is expected to commence operation in 2022.

Italy. However, there are other ways to extract energy from MSW than simply by burning it. In May, the European Commission cleared the formation of a WTE joint venture between a unit of Italian oil and gas company Eni SpA and CDP Equity SpA—a holding company of Cassa depositi e prestiti Group that invests in “Italian companies of major national interest.” The agreement establishes a company called CircularIT, which will build plants to produce biofuels and water (both for irrigation and industrial reuse) from organic municipal waste, which the company says is “in line with a circular development model.”

According to Eni, the goal of CircularIT is to help fill the infrastructure investment gap necessary to achieve targets that were set as part of the European Union’s “Circular Economy 2018” initiative, which establishes community objectives for recycling urban waste (55% in 2025, 60% in 2030, and 65% in 2035), and calls for a reduction in the 10% maximum amount of municipal waste that can be disposed of in landfills by 2035. CDP and Eni also formed a company called GreenIT, which “will build plants to produce electricity from renewable sources and will add value to real estate and abandoned public areas,” Eni said.

Methane Capture from Landfills Offers Another WTE Option

In the U.S., at least one waste management company is capturing methane from a landfill site and using the gas to power its garbage trucks. Noble Environmental is an environmental services company headquartered in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. One of Noble’s goals is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from its Westmoreland Sanitary Landfill by up to 90%, and its putting its money where its mouth is by investing $10 million to collect landfill gas and convert it into valuable natural gas to power company vehicles.

In a May interview with newsman Jon Delano, which aired on Pittsburgh’s CBS television affiliate KDKA, Rich Walton, CEO of Noble Environmental, explained, “Noble Environmental is a waste-to-energy business. So, what we do is we have traditional trash collection and we have landfill, but we really think of ourselves as a company that utilizes every bit of resource that we as a collective community provide.”

Walton admitted many people have negative views on landfills, but his company is trying to change those perceptions. He said that by taking trash and converting it to energy, the company has created “an incredibly environmentally friendly closed-system landfill.” One way Noble promotes the message is on the side of its trucks, where decals read: “Your trash is our gas.”

Landfill gas is a natural byproduct of the decomposition of organic material in landfills. The gas is composed of about half methane, which is the primary component of natural gas, half carbon dioxide (CO2), and a small amount of non-methane organic compounds. When MSW is first deposited in a landfill, it undergoes an aerobic (with oxygen) decomposition stage when little methane is generated. Then, typically within less than a year, anaerobic conditions are established and methane-producing bacteria begin to decompose the waste and generate methane. MSW landfills are the third-largest source of human-related methane emissions in the U.S., accounting for approximately 15.1% of these emissions in 2018, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

“We have a myriad of methane collection wells,” Walton said. “We have to collect that gas, and then we clean it. So, what’s produced in a landfill is not 100% pure methane—it’s not like a Marcellus well—we need to remove CO2 and we need to remove nitrogen, which can make for a really complex process and something that’s relatively challenging. But, we’ve worked through it, and it’s something that we’re very proud of.”

When asked if there was really enough gas to fuel Noble’s trucks, Walton said, “Oh yeah, absolutely.” He noted that the company also has the ability to tie into a pipeline and sell its gas as a renewable resource. “But our focus is predominantly on using the gas for our own purposes in various shapes, forms, and fashions.” ■

—Aaron Larson is POWER’s executive editor.