Technology in Construction: Predicting and Adapting to Change

This is Part I in a series that identifies technology trends in the construction industry, and offers expert advice on how companies can prepare for changes that lie ahead.

Predicting how technology will change and impact the construction job market, even in the near-term of five to 10 years, can be difficult. Moore’s law, which states that transistors per chip doubles every 2 years, combines with social factors, particularly the varying rate at which people absorb and consume new technology, to speed up or slow down adoption. These variables can cause some technologies to be available in half the time that was originally expected, while causing other technologies to be much less available than originally anticipated.

Nevertheless, by examining recent trends and historical patterns, it is possible for companies to develop a solid strategy for choosing and rolling out technology. This first in a three-part series identifies current options, looks at specific examples, and helps companies assess what fits into their own strategic plan.

Understanding Construction Project Dynamics

Before companies can understand which technologies will provide value, they must first understand which jobs are likely to change in the near future and which ones aren’t.

Media and construction technology futurists discuss “the jobsite of the future” at great length. Most of their conversations focus on far off futures where robots do all the work. These visions are informed largely by the manufacturing industry, where the popular delivery methods Lean and Six Sigma focus on assembly lines, quality control, supply chain management, and other methods of standardization. Because of this standardization, robotics has made great inroads in manufacturing.

Construction sites, however, have more variables than manufacturing, reducing the environment’s predictability. For example, no two building designs are exactly the same; project teams are always shifting, causing working relationships to be in a state of flux; and building components are typically sourced by different companies in different geographic locations. Therefore, construction jobs still involve art as well as science.

Industrial bakeries may offer a better comparison for construction sites than manufacturing plants do. Consider the similarities: both are tasked with economically producing comparable products, while facing situations that must be handled responsively. Just as a baker must monitor multiple inputs such as heat, humidity, and differences in sourced ingredients, builders also manage heat, humidity, and material quality—not to mention the engineered outcomes necessary in building systems.

The industries’ markets also share clear differences from the market for mass-produced goods. People are willing to pay more for artisanal-quality baked goods; likewise, they are willing to pay more for a construction team they can trust who is focused on providing the best construction product to meet their needs.

Client interactions for both industries are complex. Special touches may be needed when serving customers at the bakery counter, just as they are needed to keep a project owner happy. Communications are a big part of the construction process, not only for routine updates but especially when there are unexpected surprises—and communication skills are still uniquely human. Because of these considerations, the jobsite of the future may have more in common with producing brioche than ball bearings.

Computers Handle Some Tasks Better Than Others

In general, computers are shifting human work toward two kinds of tasks: ones that involve problem-solving where standard operating procedures do not exist, and flexible roles that need to acquire new information about the world, make sense of it, and communicate it to a broader team. Why is this shift occurring? Computers (and robots) are good at performing routine tasks, both manual and cognitive. In these routine tasks, a set of rules or exact procedures can be laid out.

Applying a known fix to a broken piece of equipment is a routine manual task. Troubleshooting the problem can be a non-routine task. Sizing the required piping for a system based on size and flow rates is a routine cognitive task. Determining the best routing for that pipe based on complex project considerations can be a non-routine task. While routine tasks are easy to complete with computers, non-routine tasks, both manual and cognitive, are more difficult to perform.

Construction is interesting in that it represents a series of routine tasks structured in a very non-routine way. Tradesmen are doing repetitive tasks, but because construction planning, scheduling, and sequencing are often moving targets, those tradesmen need to assemble and reassemble their routine tasks on the fly.

Consider a simple job like a laborer deciding the best way to clean up a jobsite. Complex considerations underlie the seemingly straightforward task. Where do all the materials and tools go? Should they go to the same place today that they did yesterday? How much clearance is needed across the floor? Should piles be stacked low so they don’t fall over or high to increase the clear-floor space? What is the most effective path to sweep in? The complexity of these decisions quickly escalates when considering large-scale planning.

Shifting Job Requirements

For construction companies, future success will go to those who are able to unpack repetitive, routine tasks from the jobsite and send them to offsite facilities where they can build repetitive, routine packages of work under the oversight of fewer staff in a safer way. Computers, robots, and other machinery can be used to augment the work of humans, allowing them to be more productive.

Moving work offsite will translate to productivity gains as labor during extreme weather conditions can be lessened or eliminated; busy traffic and constrained site storage will also be reduced. Eventually, robotics will progress from being relegated to offsite support to being used for on-site tasks. According to an FMI/AGC report titled “Managing Risk in the Digital Age,” 50% of current positions in the construction sector could eventually be automated.

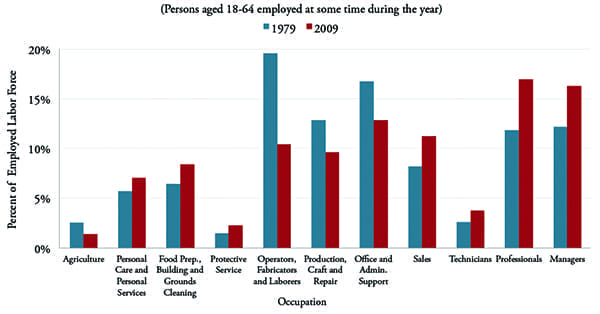

Automation will create challenges as well as benefits. As in other industries, positions will shift away from manual tasks on jobsites to ones that are more highly skilled, such as technicians and managers. A report by Thirdway.org presents data on the 1979 and 2009 U.S. occupational distributions for working men and women, aged 18–64. As is shown in Figure 1, there was significant movement away from traditionally middle-class jobs toward the other end of the spectrum.

|

|

1. There was a large shift in the workforce between 1979 and 2009, with the percentage of workers performing labor and craft jobs decreasing substantially while the percentage of people filling professional and managerial positions increased. Source: Thirdway.org |

Some of the people who are adapting well to change are becoming more technically proficient by learning to work with computers, either by fixing them or using them to become more productive. Other roles at the top of the pay scale are those that work with people, either running teams in managerial roles (Figure 2), or working in sales or customer service. At the lower end of the spectrum, people are being pushed into the non-routine manual jobs that are challenging for computers or robots but are low paying enough that there isn’t a big incentive to automate.

|

|

2. Construction projects require dedicated teams of professionals, with members fully engaged in the process. Courtesy: Graycor |

Hiring and Training Now and in the Near Future

The FMI/AGC report also finds that companies are already facing a limited supply of craft workers and field supervisors—the people at the higher end of the pay scale. As the shift toward more skilled work continues, companies will face increased costs to attract and retain top talent. Hiring and training practices will have to respond to the changes.

Several strategies can help companies adapt. One approach is to focus on youth when hiring. Companies should present to university classes, sponsor student competitions and organizations, develop internship programs, and recruit on campus. It’s also beneficial to work with organizations or programs that target college bound and non-college bound middle and high school students alike, giving them early, pre-apprenticeship training for the skilled trades.

It’s important to identify untapped markets, such as women and disadvantaged students. Many students who are seeking their place in the career world will appreciate the family mentality that exists in trade crews as they travel from jobsite to jobsite. At the same time, companies should be upfront with recruits about the downsides of certain construction jobs. Some are complex and may take place in difficult conditions. In these cases, challenge potential recruits to be “up to the task.” A benefit of the challenges that are inherent to construction is that they can reinforce teambuilding.

The energy a company invests in hiring can bring about loyalty. And the investment should not stop once an employee is hired. Mentorship programs that include in-depth, hands-on experience and candid coaching should be put in place. Company culture should foster growth and career development. All staff members, whether new hires or not, should be trained to be fully literate on any technology the company commits to adopting. Those technologies should be used as the default on projects, with project teams fully utilizing them and, when applicable, conversing intelligently with clients about them.

Companies need to help staff understand that they are a part of the change, not a victim of change. Giving people an environment where a lot is expected from them, but room for personal and professional advancement is also provided, will set companies up for success. Companies should look for new hires who have the ability to search out answers as well as display a drive for personal growth.

While the technology wave is upon us, it must be remembered that creativity and innovation are still uniquely human skills. As technology tools get more and more powerful, a company’s ability to use them to their fullest potential—combined with the ability of its employees to reframe problems and come up with novel solutions—will help them stand out.

Part 2 of this series, titled “Technology in Construction: Choosing and Implementing Solutions,” is scheduled for publication in the July 2020 issue of POWER. It will cover best practices for selecting and adopting technological tools. ■

—Weston Tanner is director of Construction Technology and Innovation with Graycor.