Should Investor-Owned Utilities Be Worried About Community Choice Aggregation?

Community choice aggregation (CCA) is only allowed in seven states currently, but recent developments in California have investor-owned utilities there worried. They fear losing up to 80% of their retail load. Could the changes in California ultimately serve as a model for other communities seeking CCA and what does that mean for the future of traditional power utilities? The answers could be unnerving.

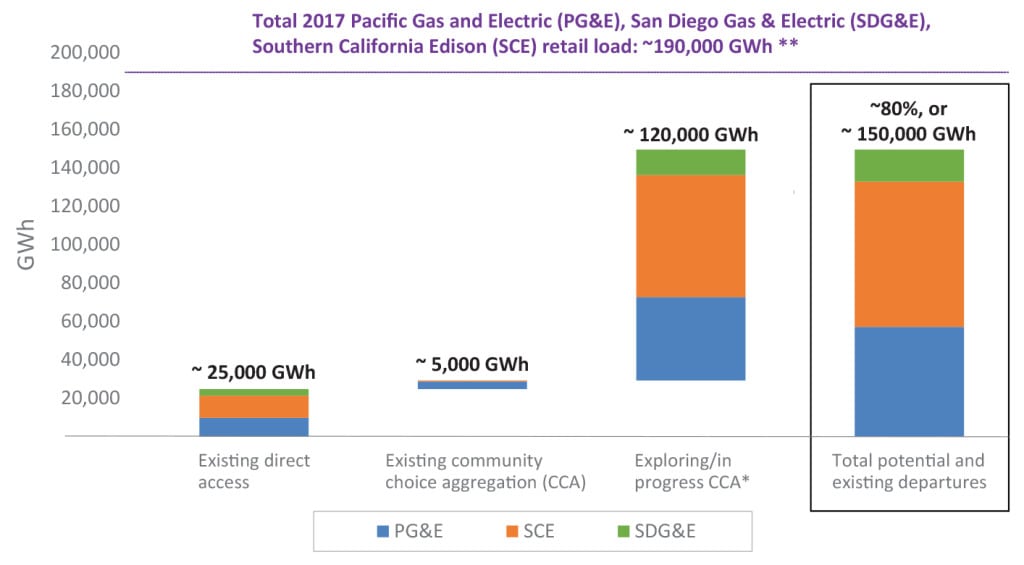

A new wave of competition is coming to California, threatening to steal up to 80% of retail sales from the three big investor-owned utilities (IOUs). In a joint filing in late January, Pacific Gas and Electric Co. (PG&E), Southern California Edison, and San Diego Gas & Electric Co. (SDG&E) said that community choice aggregation (CCA) could cause huge amounts of “load defection.” Without the proper exit fees, the utilities are worried they could suffer big financial losses.

A CCA is like the Costco of energy—a buyers’ club where local government agencies buy power on behalf of their residents. Five CCAs already serve California customers, and many of the state’s biggest cities are phasing in CCA plans. In April, San Francisco, San Mateo County, and parts of Santa Clara County—two counties south of San Francisco—will begin serving hundreds of thousands of new CCA customers.

CCA has had mixed results around the country. California’s experience, so far, has been very different from other states. Illinois, especially, was the center of CCA activity in 2014, with as many as 70% of residential customers served by aggregations. But aggregation seems to have had its day there, as numbers have shrunk in the face of maturing competitive markets.

Cost a Driver in Illinois

The CCA movement began in Massachusetts in 1997. It has been authorized in seven states, typically as part of a move toward competitive markets. In many of the states, it has been a bit player, but it has been a major force in Illinois. The Land of Lincoln had 742 communities approve municipal aggregation by citizen votes, according to the Illinois Commerce Commission. But CCA’s brief moment in the sun may be waning, according to Mark Pruitt, former head of the Illinois Power Authority and now a prominent consultant on CCA.

Illinois’ deregulation deal in 2007 resulted in a transitional period when default utility rates were frozen for six years to allow retail marketers to get started. The 2008 recession knocked down demand and market prices to well below the fixed prices from utilities. CCA was authorized through legislation in 2010, and a wave of aggregation swept through communities eager to save money.

“It was a cost savings opportunity, and it was guaranteed,” said Pruitt. “Aggregators could get 30% below the fixed price.”

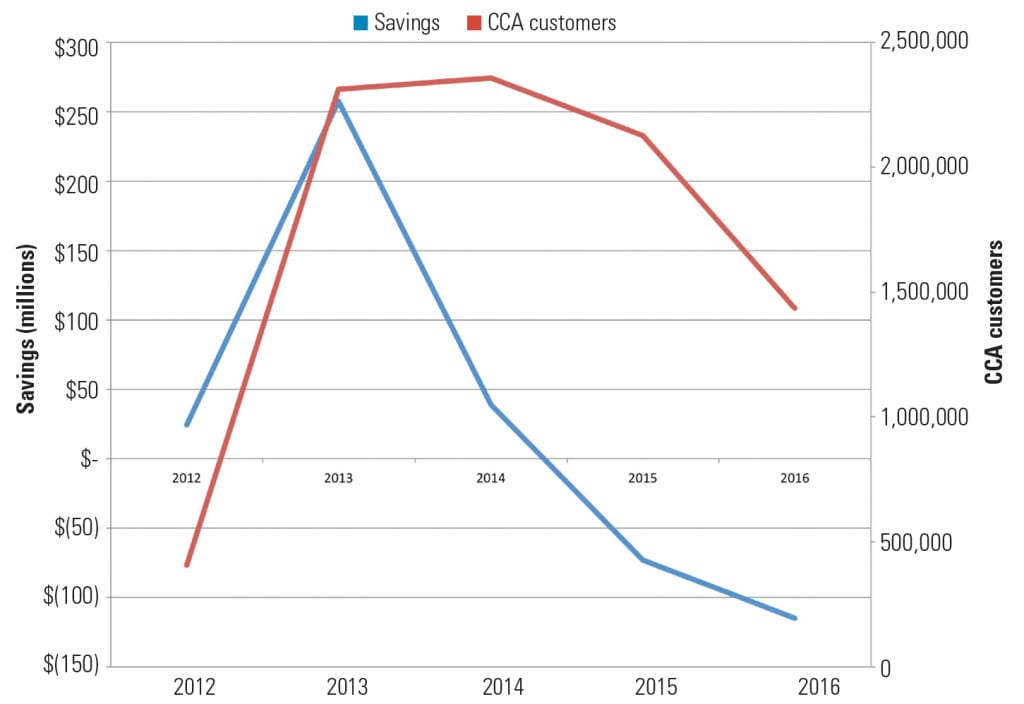

Total bill savings peaked in 2013 (Figure 1), when CCA customers saved $258 million compared to ComEd’s default rate, according to data from the Illinois Commerce Commission. But that year, ComEd’s and Ameren’s fixed price contracts started expiring, and their rates fell closer to market prices. They shifted to short-term contracts at prices similar to competitive energy suppliers. As a result, CCAs were no longer able to save money. CCA customers in ComEd’s territory actually spent $188 million more than the default rate during the past two years.

As of June 2016, 114 communities had ended their programs or put them on hiatus. The most notable change was in Chicago—the biggest CCA in Illinois (and the country). It started serving 750,000 homes and small businesses in 2013, or about two million people. But savings dried up in 2015, and most went back to ComEd.

Pruitt expects more residential load to migrate from CCAs back to utilities. “Most of them are very explicit: ‘We’re only getting into this to save money,’ ” he said. “Is it bad that they are getting out? If their goal is to save money and they can’t do that, then they have served their purpose.”

Javier Barrios, managing partner with Good Energy, disagrees. Good Energy advises 200 CCA communities in Illinois. He points out that CCA numbers are dropping in ComEd’s area, but are holding steady in Ameren’s territory. “It’s all about timing,” Barrios said. “Some of our communities are doing quite well.”

Pruitt sees a potential new use for CCAs. “If you start looking at CCA as a platform instead of a power purchasing agreement, you can see other applications.” He thinks CCAs could deliver energy efficiency programs to residents at a low cost, such as through bulk purchase of smart thermostats.

State Situations Vary

The first CCA in the country was the Cape Light Compact, which started serving Cape Cod and Martha’s Vineyard customers in 1997. So far, the Massachusetts utility commission has approved 97 community aggregation programs, and at least 60 programs are active, mostly in small towns.

CCA has experienced more success in Ohio, with big programs starting in Cincinnati, Cleveland, and the Northeast Ohio Public Energy Council (NOPEC). NOPEC, which has aggregated 500,000 buyers in 200 communities since 1999, recently went through an ugly divorce from its long-term supplier FirstEnergy Solutions, whose credit rating dropped to a perilous CCC+ rating as a result. Their new supplier, NextEra Ohio Services, offers a standard 50% renewable product for the same price. Cincinnati has gone 100% renewable via Dynegy Energy Services.

New Jersey has a handful of communities buying through aggregators like Good Energy, while New York has a pilot project in Westchester County, north of Manhattan, serving 110,000 customers in 20 towns. New York is in the process of authorizing CCA for the rest of the state, with a docket currently open.

The New York State Energy Research and Development Authority said about 70 communities throughout the state are actively considering CCA. A number of towns have already approved CCA plans in anticipation of a state rule, according to Barrios.

A push for CCA legislation in Utah encountered strong opposition from Rocky Mountain Power, but now three cities, including Salt Lake City, are working with the utility to pursue 100% renewable energy goals. Their research includes CCA as a possible vehicle.

Environmental Concerns Foster California’s CCA Growth

Clearly California is the next big thing in CCA, and it could have a bigger impact than any other state on procurement choices and policies. The Center for Climate Protection estimates that currently operational or under-development CCAs could serve 17.7 million of the 29 million people currently served by IOUs (Figure 2). San Diego, Los Angeles County (outside of the city), San Jose, and Oakland are all close to exiting.

San Diego officials have already set a goal of going to 100% renewable electricity by 2035, and they see CCA as the primary vehicle to achieve that goal. SDG&E currently has enough renewable power under contract to meet 45% of its load by 2020.

Unlike Illinois, most of the communities in California are driven by clean energy and climate desires. They want their renewables now, rather than waiting until 2030 for the state to reach its 50% renewables portfolio standard (RPS).

Marin Clean Energy (MCE) was the first of the existing CCA programs, serving 255,000 customer accounts in two counties and six other communities. It has executed 50 contracts with various suppliers, and currently gets 53% of its power from “RPS-eligible” renewable sources—well in excess of the 33% required by the state RPS by 2020. Overall, 75% of MCE’s supply comes from zero-emission sources (including large hydro, which is not an RPS-eligible resource), and it aims to go carbon-free by 2025.

Marin offers three products: a default “Light Green” option of 50% renewables, a “Deep Green” 100% renewable plan, and a new “Local Sol” offering of all locally produced solar. Deep Green power comes from renewable projects located in California, while Local Sol, which is expected to become available this spring, will be sourced entirely from solar projects within MCE’s service territory. Marin plans to increase its Light Green option to 80% renewable by 2025, with the balance coming from large hydro plants. Only 2.6% of MCE’s sales are to Deep Green customers, mostly to small businesses.

Aggregation also allows CCAs to set distributed energy policies. MCE has 9,600 net metering patrons—about 4% of its customers—who own 77 MW of solar capacity and who get paid full retail rate plus 1¢/kWh for surplus energy. It also offers a feed-in tariff for up to 15 MW of small-scale renewables. MCE is building a 10-MW solar project on a brownfield site owned by the Chevron oil refinery in Richmond.

San Francisco is finally rolling out its CCA program after literally a century of debate about public power, dating back to the Hetch Hetchy dam dispute in 1913. CleanPowerSF began serving customers in May 2016. It is enrolling customers in waves over the coming years.

Peninsula Clean Energy (PCE) started serving 80,000 customers in October, and will enroll another 220,000 next month, including tech giants like Facebook, YouTube, and Genentech. It is a joint powers authority of all 20 cities in San Mateo County, on the peninsula south of San Francisco. The CCA was approved by a unanimous vote of all 20 city councils.

Like Marin, PCE has a default product that is 50% RPS-eligible renewables plus 25% big hydro, and a green product that is 100% RPS-eligible renewables. The default product is pegged at 5% below PG&E’s price.

“It’s greener and cheaper, which is a great value proposition,” said PCE spokesperson Dan Lieberman.

Direct Energy and Constellation currently serve PCE, with implementation support from Calpine. Its plan is to build up a portfolio of contracts over time and decrease purchases from marketers. PCE recently announced the development of a 200-MW solar plant (Figure 3) with a 20-year contract at “much less” than $50/MWh, according to Lieberman. Frontier Renewables will develop the project. Frontier’s largest completed project is the 60-MW Five Points Solar Farm in Fresno County (shown in the opening photo).

So far, about 23% of customers in Marin’s cities and counties have opted out, choosing to stay with PG&E. But that rate has been declining. Seven towns joined in September, with 90% of their customers staying with MCE.

Despite these clean energy commitments, MCE has retail rates that are comparable to PG&E. The price it pays for generation is much lower, according to MCE spokesperson Jamie Tuckey, but a power charge indifference adjustment, or PCIA, imposed by PG&E brings the retail rate up to parity with PG&E.

The Exit Fee Debate

The PCIA or “exit fee” reimburses PG&E for power contracted to serve the customers who departed due to the CCA. It has been a source of controversy in California. The charge is intended to reimburse IOUs for long-term contracts previously signed to serve the customers that are now departing with the CCA, leaving remaining IOU customers “indifferent” (see “As Community Choice Aggregation Expands, the Battle Over ‘Exit Fees’ Intensifies” in the Legal & Regulatory section of this issue).

But neither side is happy with the size of the charges and how they are calculated. Utilities have nearly tripled the fee over the past two years, from 1¢/kWh to almost 3¢/kWh.

“The PCIA is flawed and does not prevent cost shifting to bundled service customers,” according to a recent filing by the three IOUs. “The current administratively-set benchmarks used to calculate PCIA rates significantly overstate the market value of the utilities’ generation portfolios.” The IOUs would prefer instead to have a “retrospective true-up to reflect actual costs and benefits.”

CCA managers agree that reform is necessary. “We have to pay our fair share, that makes sense,” said PCE’s Lieberman. “But [the PCIA] is a little bit of a black box. In theory, it should be declining over time, but it’s not.”

“I like the idea of an ‘indifference adjustment’ and not a death spiral,” he added. “PG&E provides excellent [transmission and distribution] and reliability services. But really, how high can this thing go?”

The California Community Choice Association has been exploring a number of reform options, including buying out the existing IOU contracts, or paying the PCIA up front. “Options are on the table,” according to Barbara Hale, assistant general manager for power with the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission.

Exit fee negotiations have not been helped by the utilities’ past opposition to CCAs. PG&E bankrolled Proposition 16, a ballot measure in 2010 that would have required a two-thirds vote of the public to allow a community to start or join a CCA. PG&E spent $46.1 million on the measure, but lost.

PG&E also aggressively opposed the startup of MCE, running ads and phone banks urging customers to opt out. That was likely a big factor in raising MCE’s opt-out rate to 23%, while PCE has less than a 2% opt-out rate.

The fights led to passage of a state law in 2011 that bans the use of ratepayer funds for marketing against CCAs. Sempra Energy, parent company of SDG&E, is so far the only utility to use shareholder funds to oppose CCAs.

The law ordered the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) to develop a code of conduct for utilities, “to provide Community Choice Aggregators with the opportunity to compete on a fair and equal basis with other load serving entities, and to prevent investor-owned electric utilities from using their position or market power to undermine the development or operation of aggregators.”

An Evolving Power Landscape

The growth of CCA is calling into question what the California utility market will look like in the future.

“We need to have a discussion,” Michael Picker, chair of the CPUC, wrote in an email to POWER. “The growth of third party providers—direct access, net energy metered renewables, and CCA’s—point to a growing activist trend on the part of consumers. These alternative sources of energy will likely be serving 40 percent of load by the end of this year.”

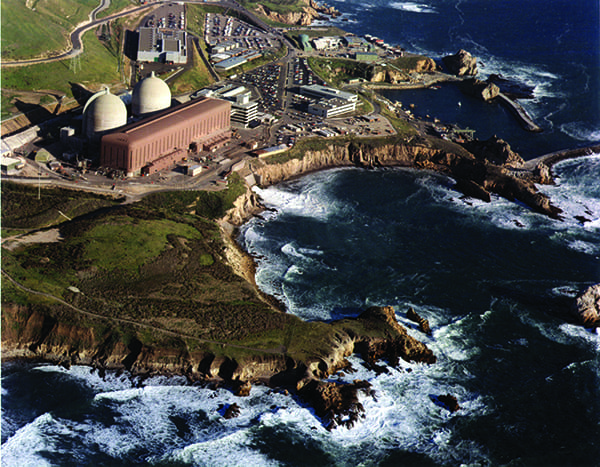

If the utilities’ long-term prediction of 80% load defection bears out, the electric business will look substantially different in California. CCA already contributed to the early demise of the Diablo Canyon nuclear plant (Figure 4). PG&E found that between CCA, energy efficiency, and the growth of distributed energy, its sales are likely to decline by as much as 30% by 2030. That, combined with a 50% RPS, leaves no room for a big baseload nuclear plant.

And the ambitious renewable goals of CCAs may be a factor in pushing legislators to be more aggressive. State Senate President Kevin de León (D-Los Angeles) recently proposed accelerating California’s 50% goal by five years and extending it to 100% by 2045.

A more competitive market—with CCA at its center—could transform IOUs into just transmission and distribution companies. CCA and the desire for clean energy could pick up where deregulation left off in 2001.

According to a recent report from Moody’s, “The growth of CCAs has … caused the California regulatory commission to publicly discuss its desire to revisit expanding retail choice by reopening Direct Access.”

Chairman Picker asked, “What does a shift from a centralized procurement model mean for our greenhouse gas reduction goals, for reliability and capacity, and for funding our public goods programs?” Although Picker didn’t provide the answers, he did note that the CPUC, along with the California Energy Commission and the California Independent System Operator, would convene a joint workshop on May 19 “to begin the exploration.” ■

—Bentham Paulos is a freelance writer and consultant specializing in energy issues.