Despite Pollution-Curbing Efforts, Dense Smog Covers Wide Swath of China

Four bouts of dense smog described as the worst air pollution in recent memory enveloped more than half of China in January, from the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei triangle in the north of the country to Nanjing in the south, via the central city of Wuhan (Figure 3). In Beijing—which bore the worst of it—the U.S. Embassy’s monitoring station reported a peak of fine particulates (PM2.5) of 755 micrograms per cubic meter (µg/m3), a level that is off the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Air Quality Index (which is limited to 500 µg/m3). Chinese monitors reported peak PM2.5 levels of 993 µg/m3, which tremendously exceeded the nation’s freshly implemented 24-hour average standard for residential areas of 75 µg/m3 and is almost 40 times more than the World Health Organization’s 24-hour average standard of just 25 µg/m3.

|

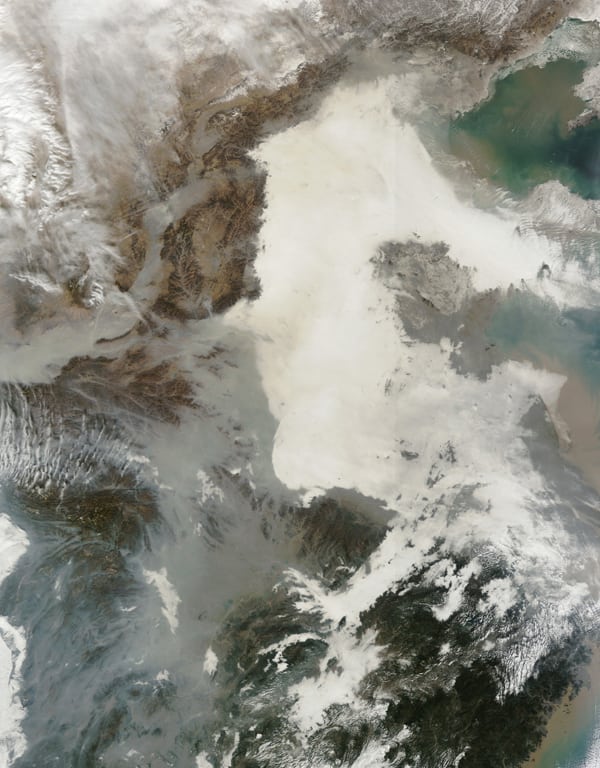

| 3. In a haze. As residents of Beijing and many other Chinese cities were warned to stay inside in January due to the worst periods of air quality in recent history, NASA’s Terra satellite captured this image from space on Jan. 14. It shows extensive haze, low clouds, and fog over northeastern China, when fine particulates peaked at 755 micrograms per cubic meter in Beijing. “The brightest areas tend to be clouds or fog, which have a tinge of gray or yellow from the air pollution. Other cloud-free areas have a pall of gray and brown smog that mostly blots out the cities below,” NASA says. In areas where the ground is visible, some of the landscape is covered with lingering snow from previous storms. Source: NASA |

Beijing is certainly no stranger to smog. Pollution episodes occur routinely; in July 2008, for example, the city forced half of private cars off the road to improve air quality in advance of the Olympic Games. But the smog that descended over the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei area over the periods of Jan. 6–8, Jan. 9–15, Jan. 17–19, Jan. 22–23, and Jan. 25–31 have been described as “much more extreme” and of a longer duration. The Beijing Meteorology Bureau attributed the spike at its worst—between Jan 10 and 13—to “very poor” conditions of dispersal. “With low pressure at the surface, wind speeds fell, humidity increased and an inversion layer formed, causing pollution to accumulate,” a spokesperson said. “It was as if someone had put a lid on the city,” the China Dialogue commented.

Research results issued by the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) in early February suggested that surging fine particulate contributions in January were caused almost 25% by vehicle emissions, 20% by coal combustion, and the remainder by “cooking.” Wang Yuesi, a CAS researcher under a group that studies haze causes and control, called for a focus on limiting industrial pollution and improving the process of coal burning—enhancing desulfurization, denitration, and dedusting in the combustion process. Dust from construction sites should also be brought under control, and more attention should be given to emissions from diesel-powered cars and to fuel quality, he said.

Other experts have gone further, calling for a coal consumption cap policy that would limit the growth of coal usage in air pollution areas. Many cite a recent World Research Institute paper that estimated there are proposals to build up to 558 GW of new coal-fired capacity in China—representing a 73% increase in the energy-intensive nation’s 2011 thermal power capacity. Compared with other Chinese cities, Beijing’s record on replacing coal with cleaner substitutes is sound, however: In 2012, it slashed its coal consumption by 700,000 metric tons.

On the renewables front, China as a whole has also made gains. It has established a goal of increasing its use of nonfossil energy to 15% of primary energy consumption by 2020, and greatly increased wind power over the last several years (see “Renewable Energy Development Thrives During China’s 12th Five-Year Plan” in our December 2012 issue). Meanwhile, the central Ministry of Environmental Protection has already begun planning coal consumption cap pilots for the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei, the Pearl River Delta, Yangtze River Delta, and Shandong city cluster as part of its “12th Five-Year Plan for Air Pollution Prevention and Control in Key Areas.” That document also sets targets for reduction of key pollutants by 2015, such as reducing PM 2.5 in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region and the Yangtze and Pearl River Deltas by 5%.

Over the short term, Beijing and other cities are developing air pollution emergency response measures, such as those taken by Beijing’s Municipal Bureau of Environmental Protection in January. During the four intense bouts of smog, Beijing suspended work at 28 construction sites, clamped down on emissions from 58 factories (that reportedly reduced particulate emissions by 30%), and took 30% of government vehicles off the road.

The haze, which made international headlines, will require longer-term solutions, Li Keqiang, who will replace Wen Jiabao as premier in March, admitted in a state radio broadcast in January. Li, the most senior official to comment on the situation to date, applauded a mandate from China’s Ministry of Environmental Protection that requires 74 major cities to monitor and publically report data for particulates and other pollutants based on new air quality standards that came into effect on Jan. 1. He also highlighted China’s efforts to regulate industry, specifically through two new regulations promulgated in February 2012 (after public outcry) that revised ambient air quality standards, including PM2.5, and developed a new definition of China’s Air Quality index. “Pollution is not a problem that emerged only a few days ago—it’s a long-term issue, and fixing it will take a long time. But we need to do something about it,” he said. “Production, construction, consumption cannot come at the price of hurting the environment.”

—Sonal Patel is POWER’s senior writer