A Legal Guide to Power Generation Mergers and Acquisitions

A myriad of issues come into play when parties execute power industry mergers and acquisitions. Part 1 of this two-part series examines what dealmakers need to know before making any transactions.

Professionals who participate in mergers and acquisitions (M&A) involving operating electric power generation assets must be well-versed in a wide variety of business and legal issues that are unique to the power generation industry. There are many details involved in the evaluation and negotiation of M&A transactions for operating projects, including key considerations such as potential regulatory approvals, that should be identified at the outset of a potential transaction.

In this two-part series in the November and December 2018 issues of POWER, we will describe the legal due diligence process, the types of agreements, and issues that are frequently encountered in the diligence review of operating electric power generation assets. We also will outline the structure of a typical acquisition agreement for these assets, and highlight typical provisions and issues that are heavily negotiated between buyers and sellers.

2017 Deals

According to a recent report by Ernst & Young, the value of global power and utilities transactions hit an eight-year high of $200.2 billion in 2017. This trend has continued through the first quarter of 2018, with the value of global power and utilities transactions rising to an all-time quarterly high of $97 billion.

In the Americas, 2017 deal value reached $102.2 billion, with the U.S. representing the highest level of activity globally ($87.9 billion). Deal value in the Americas rose to $29.4 billion in the first quarter of 2018, up 32% from the fourth quarter of 2017. Investment in generation assets rose 62% from $14.8 billion in 2016 to $24 billion in 2017.

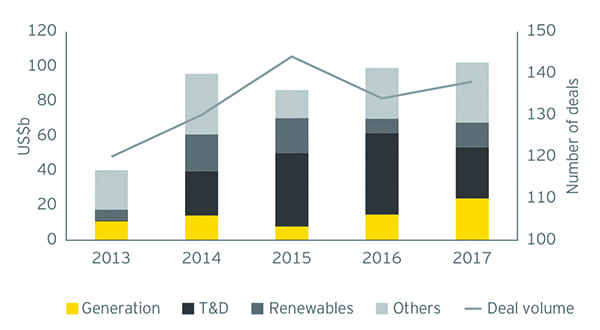

Renewable energy M&A transactions in the U.S. grew 14% in volume and 107% in deal value year-on-year, bolstered by improving project economics and increasing political and regulatory support at a state level. Figure 1 summarizes 2013–2017 deal value and volume in the Americas, by segment.

The Players. In recent years, the types of players in power M&A have expanded beyond the household corporate (strategic) names of power providers into a variety of different types of investors.

The increasing presence of private equity firms, including infrastructure-focused funds, has led to a significant increase in deal activity. Life insurance companies and pension funds have also become key players in recent years, as these investors seek to acquire conventional and renewable power generation assets as a means to improve and diversify their asset allocations.

Despite the growth in interest from financial investors, corporate investors continue to drive the majority of power M&A activity. In 2017, regional deal value contributed by corporate investors was double that of financial investors. Corporate investors acquired transmission and distribution (T&D) and integrated assets worth $57.3 billion, while financial investors acquired generation and renewable assets worth $30.2 billion.

Key Drivers. There are several key drivers of M&A activity in the power sector that motivate the desire to acquire or dispose of power generation assets. Power generation assets derive relatively attractive returns and stable cash flows as compared to many other investment sectors, particularly in the broader energy market as compared to more volatile investments in oil and gas assets.

Highly leveraged strategic companies often commence processes to dispose of noncore assets, attracting financial and other strategic buyers. Additionally, current and expected trends in commodity prices can drive power M&A activity. For example, years of low prices for natural gas in the U.S. attributable to the shale boom created an attractive opportunity for natural gas-fired projects, enabling these projects to acquire their essential fuel at historically low prices.

Regulatory policies and politics also play a key role in driving power M&A. The Obama administration’s Clean Power Plan, and the legislative agendas of several states, sought changes in the U.S. product mix away from coal, and toward natural gas and renewable sources, greatly affecting the market dynamics for power M&A.

The Trump administration has sought to unwind that agenda by withdrawing from the Paris climate agreement, unveiling the proposed Affordable Clean Energy rule, and publicly advocating for greater investment in coal and nuclear projects.

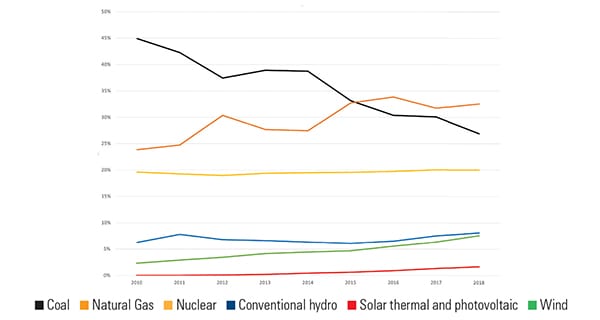

In 2015, POWER reported that natural gas surpassed coal as the U.S.’s leading electricity generation fuel source for the first time ever in April that year. Since that time, coal has continued to decline while gas has held fairly steady as the source of about a third of the nation’s electricity, up from a 16.1% share of the mix in 2000. Coal’s share of U.S. electricity generation fell over the same period from 51.8% to less than 27% through the first six months of this year. Figure 2 summarizes the energy mix in the U.S. during the period from 2010 through June 2018.

Preliminary Considerations

If a power M&A deal comes across your desk, there are several key questions that should be asked (and hopefully answered) at the outset. Some things to consider follow.

Does the Transaction Involve a Single Project or a Portfolio of Projects? Obviously, these are two very different types of transactions, impacting the scale of due diligence, valuation issues, and project-specific operational issues, among other things. In a portfolio transaction, the buyer may ascribe a very large allocation of the valuation to a subset of the largest (by size and/or revenue generation) projects, with little value allocated to the remainder. This can impact the transaction process in a number of ways—for instance, the highly valued projects are likely to be the subject of greater focus in due diligence and in the acquisition agreement, such as project-specific representations and warranties or material adverse effect thresholds. In summation, it is key to identify the value proposition early in the process.

What Types of Projects Are Involved? Different types of projects (such as coal-fired, gas-fired, solar, or wind) present unique diligence concerns (Figure 3). At the most basic level, the inputs are obviously unique to the type of facility, and the buyer must diligence the existing and potential alternative arrangements for any fuel supply, procurement, waste disposal, and more. For renewable energy projects, buyers need to understand any existing tax equity investments, and whether project eligibility for federal tax credits or other tax benefits would be impacted by the transaction.

Is the Project Output Contracted or Merchant? At a basic level, there are two ways for a power project to earn revenues: contracted or merchant (including “quasi-merchant” projects described below). A project company may enter into a long-term (typically between five and 20 years) power purchase agreement (PPA) providing for the purchase and sale of the electricity generated by the project (typically to a utility but there can be other types of off-takers), and sometimes providing for the purchase and sale of capacity and/or ancillary services. The pricing terms may consist of fixed or variable components, and there may be built-in escalation provisions. For transactions involving contracted projects, diligence of the PPA is among the most important aspects of the due diligence undertaking, as the PPA is the key value driver for the project.

Conversely, a merchant project sells its output on the spot market, without any long-term contractual commitments. One type is a “peaker” plant, which generally runs only when there is a high (or “peak”) demand for electricity. Intermittent energy sources such as wind and solar create a corresponding increase in the need for peakers that can operate to fill the demand gap created by the intermittent energy sources.

Diligence review of a merchant project obviates the need to diligence a PPA, but the buyer must have a thorough understanding of the markets and auctions in which the project participates, the seller’s historical bidding strategy, and the buyer’s bidding strategy going forward to ensure that the business plan and financial model for the acquisition are attractive.

“Quasi-merchant” projects also rely on spot electricity market prices (or short-term contracted prices) to derive their revenue streams. These projects utilize financial structures such as:

- ■ Revenue put option. A contract that stipulates if the revenues of the project from the sale of generated power are less than a stated net revenue amount, the counterparty pays the difference to the project owner, but if greater than that stated net revenue amount, the project owner is entitled to keep the difference.

- ■ Heat rate call option. A contract that provides for a swap of variable cash flows for a fixed payment stream that may be paid either to the counterparty or the project owner.

- ■ Virtual PPAs. In the case of a renewable project, a contract pursuant to which the counterparty agrees to pay the renewable project owner an agreed contract price. The project sells the generated power into the local wholesale market on a merchant basis. The project owner pays the counterparty if the generated power is sold into the market above the contract price, and the counterparty pays the project owner the difference if the generated power is sold below the contract price.

What Is the Structure for the Acquisition? Generally, private acquisitions are structured as either stock purchases or asset purchases. In the power M&A space, a typical transaction structure involves the purchase by a buyer of a top-level holding company, which in turn owns one or more project companies, which in turn own the individual projects and related assets. The group of companies that are acquired under such a structure are referred to in this article as the “acquired companies.”

Occasionally, a transaction will be structured as an asset purchase. Some instances where an asset purchase might be utilized include:

- ■ Acquisitions of projects out of a bankruptcy estate.

- ■ Situations where the seller is carving out some subset of projects less than all of the assets owned by the applicable seller entity.

- ■ Situations where the parties desire to negotiate specific assets to be assigned/excluded and specific liabilities to be assumed/retained.

From the buyer’s perspective, in the asset sale context, there is increased pressure on the drafting and the negotiations between the parties to ensure that the buyer is getting all the assets that it will need to operate the projects, that the buyer will not be assuming any unintended liabilities, and that permits and contracts may be transferred. More on this topic will be presented in Part 2 of this series in the December 2018 issue of POWER.

Is There Any Debt Associated with the Projects? A key threshold determination is to identify whether the acquired companies are subject to any indebtedness, and if so, how the parties intend to address that indebtedness as part of the transaction. If there is no debt, several aspects of the diligence and the acquisition agreement drafting can be simplified. If there is existing debt that will be paid off as part of the transaction, the transaction will often be structured as a “cash-free, debt-free” transaction such that the seller keeps all pre-closing cash and pays off all debt (usually by reducing the purchase price payable to the seller and instead using it to repay the lenders) at the time of the sale.

If there is existing debt that will stay in place post-closing (such as financing that the buyer views as favorable and unlikely to be capable of replication under then current market conditions), the buyer will have to review what consents of the lenders will be required and whether there are any structural considerations that might obviate the need for lender consent. The change in control provisions contained in the debt documents might not require lender consent for transferees that meet certain operational and financial criteria. If a goal of the transaction is to “thread the needle” through the change of control parameters, a key part of the due diligence will be matching up the legal provisions of the existing debt documents with the quantitative facts applicable to the buyer.

What Are the Existing Employee, and Operations and Maintenance (O&M) Arrangements? Depending on the seller and the type of assets, the acquired companies may employ few or no employees. A few reasons for that include:

- ■ Some projects require very few human resources for their operations.

- ■ Larger strategic companies may employ people at a higher entity level and dedicate those employees to specific projects in practice.

- ■ Financial investors may have little or no operations personnel, and instead contract with third parties to provide O&M services.

Even if few or no employees come along with the stock purchase of the acquired companies, the seller may negotiate for the buyer to be required to hire certain individuals from affiliates or service providers, and to maintain their compensation and benefits for some period of time.

From the buyer’s perspective, the buyer needs to be sure that it can obtain all the human resources, either by way of acquired employees or replacement O&M services, to operate the projects post-closing of the acquisition. If the buyer will be hiring employees, the buyer needs to identify key employees and make sure they are included in the group of hired employees. If the buyer will agree to maintain certain compensation and benefit levels for the acquired employees, the buyer needs to be aware of any practical issues associated with onboarding new employees into the buyer’s organization.

It is one thing to agree to maintain comparable compensation and benefit levels in a holistic sense, but the buyer needs to investigate exactly how those benefits can be integrated with the buyer’s own benefit plans.

The buyer will also need to identify whether it will need any post-closing transition services from the seller. This need may be particularly acute for financial buyers, who may not have the operational and administrative resources to operate the projects immediately following the closing. Buyers should be aware that although many sellers are willing to provide such transition services (for a price), other sellers are not in the business of providing services to third parties in any form, and thus the buyer will need to make external arrangements.

Are There Any Required Contractual Third-Party Consents? As is the case in any acquisition, a key component of the due diligence exercise is to identify whether any third-party consents are required to close the transaction. The usual suspects for this item include joint venture partners (if any projects are less than 100% owned), lenders (if there is any existing debt), and commercial contract counterparties. The acquisition agreement will likely contain covenants and conditions precedent relating to obtaining material third-party consents, as discussed in Part 2 of this series in the December 2018 issue of POWER.

Are There Any Local Issues that Require Engagement of Local Counsel? The acquisition agreement for a power M&A transaction is often governed by the law of a commonly used jurisdiction, such as New York or Delaware, rather than dependent on the geographic location of the project. Nonetheless, a transaction will often present unique local law issues. From a real estate perspective, a transaction might involve issues around title and zoning of the projects to be acquired, and whether or not state and local taxes are triggered by the transaction.

Many transactions involve specific local issues around allocation of natural resources, such as water use, and the buyer will need to be very familiar with practical and legal constraints impacting the ability to obtain sufficient water and other resources for post-closing operations. A project may have matters pending before a state or local environmental regulator that a buyer will want to understand in valuing and/or consummating a transaction. These are just a few examples of where local counsel can add value to a transaction.

Regulatory Approvals

Power M&A in the U.S. is potentially subject to regulation at several levels of government, and obtaining the requisite governmental approvals is often the gating item for closing the transaction. The following potential approvals often need to be considered.

FPA 203. Section 203(a)(1) of the Federal Power Act (FPA) requires any person owning or operating a facility subject to the jurisdiction of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) to obtain FERC authorization prior to, among other things, disposing of the facility or any part thereof with a value in excess of $10 million. FERC has interpreted FPA Section 203(a)(1) to require authorization for direct or indirect transfers of ownership and/or control of a subject facility. FERC generally considers a transfer of ownership or control to occur when there is a transfer of 10% or more of the ownership in a subject facility.

HSR Act. The Hart-Scott-Rodino Antitrust Improvements Act of 1976, as amended (HSR Act), requires that before certain mergers, tender offers, or other acquisition transactions can be completed, both parties must file a “notification and report form” with the Federal Trade Commission and the Assistant Attorney General in charge of the Antitrust Division of the Department of Justice, and wait a prescribed time period, during which those regulatory agencies will assess whether the proposed transaction violates U.S. antitrust laws or could cause an anti-competitive effect in the parties’ markets. Under the 2018 HSR Act thresholds, notification of mergers or acquisitions will be required if:

- ■ The acquiring party will hold another person’s assets or voting securities valued in excess of $84.4 million, and the transaction involves both one party with annual net sales or total assets in excess of $16.9 million and another party with annual net sales or total assets in excess of $168.8 million.

- ■ The acquiring party will hold assets or voting securities of another person valued in excess of $337.6 million.

PUCs. State public utility commissions (PUCs) regulate the rates and services of public utilities. Power M&A transactions may require state and local approvals under statutes and PUC regulations.

RTOs/ISOs. Power projects are also regulated by regional oversight entities. Categories of these regulators include the following regulatory organizations:

- ■ An independent system operator (ISO) coordinates, controls, and monitors the operation of the electrical power system, usually within a single U.S. state, but sometimes encompassing multiple states.

- ■ A regional transmission organization (RTO) coordinates, controls, and monitors a multi-state electric grid. RTOs typically perform the same functions as ISOs, but cover a larger geographic area.

A key preliminary task will be to identify the geographic location of the projects and the applicable regulators.

FCC Approvals. Power plants often hold Federal Communications Commission (FCC) licenses, and transfers of control of the license (either by asset sale or indirectly by stock sale) may require a filing with the FCC.

CFIUS. The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) is an inter-agency committee of the U.S. government that reviews the national security implications of foreign investments in U.S. companies or operations. During the CFIUS review process, CFIUS will determine:

- ■ Whether the foreign investment is a “covered” transaction (a transaction that would result in foreign control of any person engaged in interstate commerce in the U.S.).

- ■ If the foreign investment does constitute a covered transaction, whether the transaction raises potential U.S. national security or critical infrastructure implications. If a transaction could result in “control” of a U.S. business (including U.S. operations of an international business) by a foreign person, the parties will need to consider whether a CFIUS filing is required.

Due Diligence

As is the case in many other transactions, the due diligence exercise in power M&A transactions will involve a number of parallel work streams. Various groups of people will be looking at financial, technical, and legal due diligence materials. While the technical diligence component might involve site visits and interviews, the legal due diligence exercise will mostly involve document review, and participation in a question and answer (Q&A) process.

Document review includes the review of contracts, permits, court orders, and other legal documents that are provided in a data room or that are publicly available. For the most part, data rooms in recent years have been virtual-only data rooms, where the materials are all available in a controlled, online database. In addition to the document review, there will also typically be an iterative Q&A process where the buyers and their advisors submit diligence questions to the seller.

Below is a list of the typical materials you may encounter in the data room for a power M&A transaction, along with a short description of each type of document.

Existing Financing. The acquired companies may have credit agreements that provide for credit facilities at the project company level or at the portfolio holding company level, along with ancillary financing agreements such as guarantees, security agreements, and other loan documents.

PPA/Hedges. As noted earlier, a PPA provides for the purchase and sale of the electricity generated by the project, and the project may have hedges in place that create or otherwise impact the project’s revenue stream.

Interconnection. The interconnection agreement provides for the interconnection of the project to the electric grid. The interconnection agreement deals with matters such as metering, infrastructure requirements, and access.

O&M. The O&M agreement provides for a contract service provider to provide O&M services to the project for an agreed upon price and duration.

Fuel. Fuel supply and transportation agreements dictate the terms upon which the project will acquire its fuel sources from a supplier, such as supplies of natural gas or coal.

Disposal Agreements. Disposal agreements dictate the terms upon which an off-taker will dispose of byproducts produced from the project, such as coal ash.

Water Management. Water management agreements provide for third parties to provide fresh water and dispose of used water on behalf of the project.

Energy Management. Energy management agreements arrange for a service provider to administer power marketing, scheduling services, fuel management, and portfolio optimization services to a project.

Permitting. The data room will likely contain a number of permits related to the construction, maintenance, and operation of the project, including those related to any historical or proposed expansions, or other modifications to the project.

Environmental. The data room often contains a number of materials related to environmental compliance, including permits, notices of violations, consent decrees, and agreements with regulators. Environmental specialists will also be able to obtain useful materials from publicly available sites maintained by governmental agencies.

Employment and Benefits. The data room may contain materials related to employees and employee benefits, depending on whether employees will transfer to the buyer’s organization as part of the transaction. If employees will be included in the transaction, the data room will likely contain lists of employees and their compensation levels, an organizational structure chart, copies of any collective bargaining agreements, copies of the benefit plans in which those employees participate and summary descriptions of the same, employee policies and manuals, summaries of any potential litigation matters involving employees or benefit plans, and similar items.

Real Estate. The data room will likely contain a number of materials related to real estate matters, including title policies, title commitments, title reports, surveys, plats, vesting deeds, easements, licenses, leases, and other agreements.

Credit Supports. The data room often contains documentation of credit supports that the acquired companies or the seller maintain for the benefit of third parties, such as letters of credit or bonds posted for the benefit of an ISO.

Corporate Materials. The data room will likely contain formation and governance documents for the acquired companies. In situations where the acquired companies are wholly owned directly or indirectly by a single seller, these documents are typically relatively simple. In situations where the acquired companies are not wholly owned directly or indirectly by a single seller, there may be joint venture agreements that are significantly more complex.

Q&A

In the Q&A process, the buyer submits due diligence questions to the seller (typically in a spreadsheet or similar format), in order for the buyer to formulate its bid and understand any risks associated with the transaction. The seller will respond with either discrete factual responses or a reference to where the answer can be found in the data room or elsewhere.

The Q&A process can be a very helpful tool for the buyer to hone its diligence and seek the seller’s view on particular questions (such as the meaning of an ambiguous term in the project agreements, alternative supply arrangements that might be available in the marketplace, potential expansion opportunities, and perspectives on the view of governmental authorities), but ultimately, the buyer should recognize that the information provided as part of the Q&A process is often provided without any express representation or warranty by the seller.

Given the prevalence of non-reliance and exclusive remedy provisions in acquisition agreements, which collectively operate to limit a buyer’s remedies to the indemnification provisions in respect of the express representations and warranties set forth in the acquisition agreement, the buyer must typically rely on information produced from the Q&A process at its own risk. Buyers may also be successful in negotiating for additional operational representations and warranties in the acquisition agreement as a result of these limitations.

What is to be done with the knowledge gleaned from the review of the data room materials and the Q&A process? The output from the legal due diligence process can take a wide variety of forms. On one end of the spectrum, it could be a summary highlighting only “red flags” or the most critical findings of the diligence process. On the other end of the spectrum is a detailed contract summary for each document reviewed. It is critical to establish at the outset what work product will benefit the various constituencies involved, including the buyer’s decision-makers, legal department, and operations team.

Many buyers prefer something toward the middle of this spectrum, with an executive summary of key findings, a detailed listing of documents reviewed, and more in-depth summaries of only the key issues or agreements (as opposed to summaries of all documents reviewed).

Buyers should be aware of the interplay of the roles of external constituencies in preparing their due diligence reports. For example, if a buyer will incur acquisition financing in connection with the transaction, it is likely that the lender will seek to review the due diligence report (in the U.S., typically on a “non-reliance” basis). In addition, if the parties procure representation and warranty insurance in connection with the transaction, as has become increasingly more popular in recent years, it is likely that the insurer will also seek to review the due diligence report. The insurer will also likely conduct a thorough investigation of the buyer’s diligence (including separate calls with the buyer’s subject matter experts, particularly in environmental matters) to make sure that the buyer has undertaken sufficient steps to uncover potential problems, as the insurer seeks to cover the risk of only what is truly unknown. Thus, buyers should expect that insurers will pay close attention to the buyer’s due diligence report to make sure that the buyer has investigated appropriately and that any issues raised in the report have been appropriately “run to ground.” ■

—Jeff M. Dobbs and Robert S. Goldberg are both partners with Mayer Brown LLP in the firm’s Houston, Texas, office. Part 2 of this series will be published in the December 2018 issue of POWER. Additional reference information is available at: http://bit.ly/Part1_MA