Best Practices for Aligning Safety Metrics, Incentives, and Performance

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration requires certain incidents to be recorded and reported, which generates a set of statistics that many companies use to gauge safety performance. However, other metrics may be better predictors.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) requires all employers with more than 10 employees, and whose establishments are not classified as a partially exempt industry, to report work-related injuries and illnesses. Companies must post statistics annually, such as the total number of deaths, cases with days away from work, cases with job transfers or restrictions, and total other recordable cases.

The numbers are eye-opening—on average, more than 12 people die on the job every single day in the U.S., and more than one million cases each year require days away from work to recuperate. But these statistics don’t tell the whole story. Each number represents people who did not expect to be killed or injured on the job when they went to work. Companies want those numbers to be zero, but how can they get there?

Assessing the Safety Culture

It’s important to understand that OSHA metrics are trailing indicators of safety performance. Once a person is injured and the incident recorded, the only thing a company can do is try not to let something similar happen again. So while OSHA data offers a useful snapshot of historical performance, better, more predictive metrics are needed to gauge safety trends within a company and determine what areas must be improved to prevent future incidents.

Conducting regular safety audits is one option. These often include a standard checklist of safety inspection items, such as: Are workers wearing their personal protective equipment? Have they locked out the system they’re working on? Has confined space monitoring been completed, if necessary? While audits provide a standard method for monitoring safety, some safety experts argue that they rarely do more than verify whether or not workers are meeting the minimum requirements.

According to Gary Higbee, president of Higbee & Associates Inc.—a full-service safety training and consulting firm—and co-author of Inside Out: Rethinking Traditional Safety Management Paradigms, safety culture is not driven by compliance. He says compliance is extremely important—a legal obligation—but employees need training on individual skills that they can use everywhere.

“Do they look before they move? Are they working at a reasonable speed? Are they in a good body position related to the work?” asked Higbee. “Those are behaviors that employees control.”

Behavior Observations

Higbee recommends conducting observations that evaluate employee behaviors. He says that there are four “states”—or conditions—that lead to errors: rushing, frustration, fatigue, and complacency. The significance of an error is a function of luck and the amount of hazardous energy that is present in the vicinity of an incident, but it’s the behaviors that cause it.

Some estimates suggest that up to 90% of workplace accidents are caused by human error. An error may or may not lead to an injury, but if a company can modify employee behaviors to prevent errors from occurring, injury rates are bound to improve.

For example, a worker could lose his grip on a 10-pound sledgehammer. In one instance, the hammer could fall harmlessly to the deck grating directly below, causing no real harm. In another case, the hammer could fall through an opening in the deck grating and strike someone on the ground 50 feet below. The error—dropping the hammer—was the same in either case, but the result of the incident would be considerably different.

The question a company must ask is: Why was the hammer dropped? This is where many people may not consider all of the factors that led to the error. It is easy to say such things as: “It was an accident.” “It slipped.” “It was an act of God.” or “Stuff happens.”

But is it really that simple? If we try to determine which of Higbee’s four states led to the error, we may find that the accident was predictable. Consider the states and some questions that could be asked:

■ Rushing. Did the incident occur near the end of the day as the worker was trying to finish a job so he could go home? Was there time pressure placed on the worker to get a piece of equipment returned to service?

■ Frustration. Had the individual been struggling for an extended period of time on a difficult task with little success? Did he feel that he was not getting the help that he needed?

■ Fatigue. Was the person working an abnormal shift or more hours than normal? Does the individual have a young child who may have interrupted sleep the night before?

■ Complacency. Had the person done the job numerous times before without incident? Was the work considered a simple task that did not require complete focus?

Companies try to compensate for errors in many ways. Personal protective equipment, such as a hard hat protecting an employee from being injured by falling objects, or a lanyard keeping a tool from falling beyond a certain point, can help, but in these examples the errors still happen. One key to preventing injuries is to reduce the number of errors that occur in the first place.

To get a snapshot of a work group’s safety climate, Higbee interviews employees and asks them to rank—from 0 to 10—how they feel in regard to each of the states at that particular moment in time. While individual responses may be somewhat arbitrary, a group’s averages can point to previously unidentified problems, which can then be dealt with to improve the safety climate.

Some examples of issues that could be unearthed include unnecessary time pressure being placed on workers by a supervisor, causing them to rush; overly restrictive policies, resulting in worker frustration; sporadically scheduled breaks, resulting in worker fatigue; or a lack of variety in work assignments, leading to complacency. Survey results can be used in various ways to improve situations and reduce the likelihood of errors.

Safe Work Traits

Higbee suggests that safety inspectors also monitor work habits. By that he means specific behaviors, such as workers having their eyes and mind on the task they are performing, which is important for error prevention. Other factors to check include workers’ ability to recognize where the “line of fire” (a hazardous area with increased risk of injury) is, and where there is the potential for them to lose their balance, traction, or grip. Getting workers in the habit of looking before they move and staying engaged in the job at hand goes a long way toward reducing accidents.

In many cases, safety training will need to include topics on awareness, so that individuals grow more alert to their surroundings. The traits need to become second nature to the point that workers incorporate safe behaviors into their everyday lives, whether at work or at home.

Accurate Guidelines

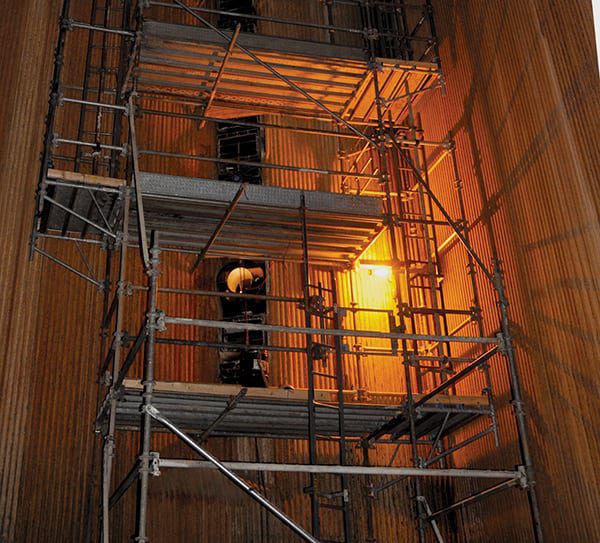

While safe work traits are essential, workers also need good direction. Peter Verhoef, managing director of 12hoist4u, a Netherlands-based staffing firm specializing in hoisting and lifting that in October achieved six consecutive years without a lost time injury while working in a notoriously dangerous field (Figure 1), believes the most important tool available to improve safety performance is well-crafted rules and regulations.

|

| 1. Serious business. According to OSHA archives, an average of 71 fatalities occur each year as a result of crane accidents. Courtesy: 12hoist4u |

He says subject matter experts and technical authorities must be involved in developing the policies and procedures to ensure that they are comprehensive and sound. 12hoist4u works with industry organizations and regulatory bodies to set safety standards, training standards, and operational best practices. Of course, a company must also have workers with a procedure-based mentality, a practical understanding of the guidelines, and dedication to compliance.

Verhoef likens safety statistics to an iceberg. As is the case with an iceberg, what is visible above the surface is often much less than what is lurking below the waterline. When it comes to safety metrics, the number of injuries acknowledged is often far less than the number of close calls falling under the radar (Figure 2).

|

| 2. Eyes and mind on task. Gloves and hard hats are essential safety gear, but staying focused on the job is even more important. Courtesy: 12hoist4u |

Near-Miss Reporting

With that thought in mind, one metric that many safety professionals use to gauge a work group’s safety performance is the number of near misses or close calls they have. Near misses are generally thought to be precursors of injuries. Statistically speaking, the more near misses a group or person has, the more likely it is that one of them will result in a serious incident. Near-miss reporting and investigation allows a company to identify and control hazards before a more serious incident occurs, and, if reported accurately, trends can indicate whether performance is improving or deteriorating.

“I’m very interested in incidents, especially when they look to be of minor importance,” said Verhoef. “Subsequent real in-depth investigation, making use of expert knowledge, might unveil root causes that one had not previously thought of. Seemingly minor incidents might all be signs of that part of the iceberg that is below the surface.”

But near-miss tracking can be very challenging. According to Pat Bray, a 35-year Otter Tail Power Co. veteran who spent the majority of his time as the safety and training coordinator at a coal-fired power plant, most companies are unsuccessful using the near-miss metric. The reason: Few people want to admit their mistakes, especially if doing so may put them at risk for punishment.

“No one wants to stand in front of their peers and say ‘I had a close call. I screwed up and almost got hurt. I want to share that with you,’” Bray said. “Even though it’s a really good leading indicator, it’s one that we really have a hard time capturing.”

Eight Focus Areas

Safway Services LLC—a company that offers access, scaffolding, insulation, fireproofing, surface preparation, and coating solutions to the power industry—has implemented a behavior-based safety program that it believes is improving its safety culture. The system is based on a construction industry initiative fostered by the Center for Construction Research and Training (known as CPWR), the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), and OSHA.

Safway’s program focuses on eight objectives, which are taken from the CPWR-produced booklet, Strengthening Jobsite Safety Climate: Eight Worksheets to Help You Use and Improve Leading Indicators. The objectives include:

■ Demonstrating management commitment.

■ Ensuring safety is aligned and integrated throughout the company.

■ Requiring accountability at all levels.

■ Developing site leadership to facilitate a strong safety climate.

■ Empowering employees to be involved in all safety processes.

■ Communicating all safety matters proactively and reactively.

■ Providing training at all levels, tailored to specific roles and responsibilities.

■ Engaging with owners and/or clients on safety planning, process, and culture.

Each of the objectives is assessed on a five-level scoring scale indicating a maturity ranking for the focus area. The five levels are: uninformed, reactive, compliant, proactive, and exemplary.

Part of the process of becoming exemplary involves periodically assessing if the company’s espoused safety-related values are aligned with other values, such as production and cost reductions. Gathering both quantitative (such as surveys and audits) and qualitative (such as informal interviews and focus groups) safety climate data from workers and managers helps determine if there is a gap between what the company says about its safety values and what its employees perceive.

“First and foremost, we believe that our business leaders—starting with me—own driving great safety,” said Bill Hayes, president and CEO of Safway Group. “We believe positive and constant reinforcement of our key safety messages is critical to fostering a culture of safety.”

Part of that includes publishing its safety metrics across its 95-branch network, because Safway believes visibility of safety results and accountability for safety performance is essential. But Hayes says the most important aspects are training frontline leaders, keeping programs current, and staying up-to-date on leading indicators.

Having the benefit of working with many companies in various industries (Figure 3) gives Safway the opportunity to see and evaluate what other businesses are doing. It says the best companies that it works with are very proactive in task planning (Figure 4) and employee observation processes. They are also very good at ensuring employee accountability.

But in order to hold people accountable, workers have to be properly trained. For that, Safway has its own “Training University” through which it has trained more than 40,000 employees and more than 40,000 customer and partner representatives, including OSHA and other regulatory professionals. Many of the company’s initiatives are designed to involve employees, who it says have the power to stop work any time they feel safety is compromised.

“Safety is in my blood,” says Hayes. “We won’t be near satisfied until we are at zero injuries.” But even then, he suggests, there will be more work to be done.

Bray agrees with Hayes’ sentiment. He says that ownership and top management within companies need to sincerely and objectively make safety a core value and not just give it lip service.

“The bottom line is that if management is not openly and obviously sincere about managing safety within the organization, the workers are going to pick up on that,” Bray said.

For more information about the CPWR safety initiative, see a copy of its booklet online at: bit.ly/1zUrbxA.

Pay for Performance?

Many safety professionals object vehemently when the topic of incentives is discussed. Some say incentives encourage under reporting and, logically speaking, certain types of incentives can create conflicts of interest. If workers receive monetary bonuses or awards based on remaining below a certain number of injuries for example, it is in their pocketbook’s best interest not to report incidents unless absolutely necessary.

“The biggest problem with safety incentive programs is that they do not work the way people expect them to,” said Verhoef. “Programs that reward employees with monetary or tangible rewards for an expected level of performance can become routine, ineffective, and irrelevant with the passing of time.”

Another problem can arise in trying to make the award meaningful. If the workers do not consider the incentive adequate, it can result in discontent and can end up being counterproductive. But is there a way to effectively promote safety with rewards for good performance? The jury is still out on that question, but Bray thinks the spontaneous recognition model could work.

The idea is based on a reward concept Bray learned about in a training session several years ago. The crew leader, or person in charge of the workers, chose one focus area each day unbeknownst to the workers, and then paid particular attention to how the workers were meeting expectations in that area on the given day. If the work group met or exceeded the standard in the focus area, the leader would provide some form of positive recognition on the spot.

The reward could be a heartfelt thank you, a free soda, or ice cream for the group during a break. Another option is for the supervisor to keep an ongoing tally of daily results and provide a more significant reward once a certain threshold is reached.

“It needs to be spontaneous, it needs to be genuine, and it needs to feel significant,” Bray said.

12hoist4u also uses “there and then” rewards to some extent. A small reward, such as a dinner voucher for the employee and a guest, is awarded at times for a single observed safe act. Getting a guest in on the deal can add a very useful supporter of safe working habits to the mix—the employee’s spouse or partner.

“A voucher shows immediate recognition of a safe behavior and good practice from the management that noticed it to the individual receiving the reward and their peers,” said Verhoef.

But safety incentives are often difficult to administer. Some supervisors may believe in the program while others do not, leading to inequity within a facility. There is also the risk for abuse or favoritism in how the awards are distributed. Any perceived bias is sure to disrupt the program.

Upper Management Involvement

One complaint sometimes heard within labor circles is that upper management is not visibly engaged in monitoring and promoting safety in the field. Some people argue that leaders could show more involvement by assuming responsibility for awarding small incentives rather than leaving the task to immediate supervisors.

For example, a $20 bill given out by a plant manager who witnesses a safely performed job while touring a facility not only offers unexpected spontaneous recognition from upper management, but it also demonstrates that the leader is paying attention to safety in the workplace and notices when jobs are performed correctly. Although a small gift, the gesture could leave a lasting impression on a work group.

In the end, however, the best safety incentive is having a safe workplace in which to do one’s job. When workers feel supported in the safe completion of tasks and appreciated for demonstrating safe work behaviors, morale and productivity benefit. Implementing and managing a well-conceived safety program can help a company develop a culture in which safety is truly a top priority. ■

—Aaron Larson is a POWER associate editor.