Power in Mexico: A Regulatory Framework with Little Flexibility

Mexico’s federal government retains almost total control over who builds and owns what electricity infrastructure. But if you know how to work within the strict constraints, it is possible to engage in profitable projects.

Article 27 of the Mexican constitution states that the electricity sector is of strategic importance for national sovereignty and that therefore the state, via the vertically integrated Comisión Federal de Electricidad (CFE), should hold a monopoly over the public service of electricity. Originally, this meant that only the CFE could generate electricity, own transmission lines, and distribute electricity to the general population. During the 1980s, when oil prices fell, Mexico looked at reforming the sector to increase the role of the private sector; however, reform didn’t arrive until the 1990s.

Reforms in the early 1990s allowed the private sector to participate in the power generation industry in four ways:

-

Via the independent power producer (IPP) process, whereby bids are tendered out by the CFE.

-

By cogeneration or self-supply, whereby a company needs to own a stake in the production company or be co-owner of the power production facility to furnish its own electricity needs.

-

Private producers can produce power for export, as do Sempra Energy and Intergen in Baja, California.

-

A rarely used exception for projects less than 20 MW.

The IPP and cogeneration approaches are by far the most important.

Beyond power generation, companies can participate in other aspects of the electricity sector via the Obras Publica Financiada (OPF), which allows private companies to become involved in public works.

Pros and Cons of IPP Projects

In 1992 the Mexican government, then under President Carlos Salinas, amended the Electricity Public Service Law (Ley del Servicio Público de Energía Eléctrica) to allow for further participation of the private sector. The IPP program that he initiated allows private companies to both build and operate power plants in Mexico, on the condition that the resulting electricity must be sold to the CFE.

In Mexico there is no open market; private companies cannot simply come in and build a plant. Instead, they need to wait for a tender by the CFE, bid, and then, if successful, the plants normally sign a 25-year power purchase agreement (PPA). Then, depending on the exact nature of the contract, ownership will normally shift to the CFE. The CFE also retains a call option on the development.

One of the advantages of the IPP program is the CFE’s good reputation in the financial markets — together with the long-term build, operate, and transfer nature — means that the project financing can be spread over 25 years and that companies can be sure that they will be paid on time and in full.

Estefano Conde, communications manager in the CFE, explains that the CFE is rated BBB by Standard & Poor’s. The bidding process normally lasts about six months before the winning bid is declared, and the entire process is generally considered to be extremely competitive. Potential entrants to the sector need to be sure of their financing before submitting a bid and, due to financial conditions and financial institutions’ desire to spread their risk, it is unlikely that a single bank will underwrite the risk; a syndication is more likely. Due to the difficulties of financing in the current climate and the high number of bidders, those who have access to international financial markets will be at an advantage.

Shaving Peaks with Cogeneration and Self-Supply

The cogeneration (co-ownership) and self-supply system allows an enterprise to "opt out" of being supplied by the CFE and instead generate its own electricity. This can be as simple as buying a generator or involve more complicated structures whereby the customers are required to hold a nominal share of a generation company.

The way that the tariffs are structured in Mexico means that peak hour industrial usage is expensive, which encourages many large consumers to move toward generating their own electricity.

Juan Carlos Quintero, country head of Wärtsilä Mexico, a specialized power plant developer, observes that his company has seen an increase in interest in their cogeneration plants specifically for peak hour use.

Francisco Haro, director general of Ottomotores, a subsidiary company of TT Electronics PLC, specialized in manufacturing and distributing generating sets and commercializing uninterruptible energy systems, argues that, rather then being a backup in the case of blackout or brownout, his product can out-compete the CFE on price: "What we have seen is that with the peak cost of energy, many people are using a genset as a way of ‘self consumption’ [sic]. Due to the high cost of this peak energy, we worked out that a genset can actually pay itself back over a period of two to three years." Haro believes that this lack of competitiveness is due to a lack of investment in infrastructure by the CFE.

Fernando Calvillo is CEO of Fermaca, a company with more than 40 years’ experience in the development and construction of infrastructure in Mexico’s key sectors, focusing on natural gas transformation systems, oil product terminals, and power generation plants. He maintains that the CFE has some good intentions in terms of investments — for example, its planned move toward natural gas — however, it needs more resources for investments in pipelines, which would make CFE’s electricity more competitive. For the time being though, cogeneration is an attractive option.

A major barrier to the profitability of cogeneration is, however, the unique nature of the Mexican constitution that decrees that cogeneration schemes cannot sell excess energy to the grid; they must use it or lose it.

High Hurdles for OPF Projects

The OPF is a part of the Proyectos de Impacto Diferido en el Registro del Gasto (PIDIREGAS) scheme, which has been the main mechanism for private sector entry into the energy industry in all tenders except for IPPs. OPF schemes are fixed price construction projects whereby the project developer receives a payment upon completion when ownership is passed to the CFE. Due to the high cost of such projects, most companies cannot manage this off their balance sheets, meaning that they need access to financing to bid for an OPF.

Unlike some contracts issued by Petróleos Mexicanos (PEMEX), the CFE generally issues contracts in U.S. dollars. One of the main criticisms of the PIDIREGAS process is that the CFE sets very high tender conditions for entry, so although it has been successful at attracting world-class companies, it has been considerably less successful at attracting local companies to bid or even in encouraging joint ventures. Critics also argue that the same problem emerges with general contracts with the CFE, which is that there is a selection of "preferred bidders" who remain close to the CFE, and it is difficult for outsiders to join them.

The OPF only generates assets for the bidder once construction of a specific asset is complete, so a very strong balance sheet or access to credit are required. Ygor Guilarte, managing director of Yokogawa Mexico, argues that "The CFE is extremely strong financially speaking. Its strength allows it to execute its own projects without resorting to external funding from suppliers." The CFE’s financial strength allows the company to dictate very tough terms to its would-be suppliers.

Subsidies: A Sacred Cow

The Mexican federal government provides considerable subsidies on the final consumer cost of energy. This strategy was designed to share Mexico’s oil wealth among the population. Traditionally, the resulting CFE deficit on the federal budget has been financed by the huge profits of PEMEX, the state monopoly in the hydrocarbons and petrochemicals sectors.

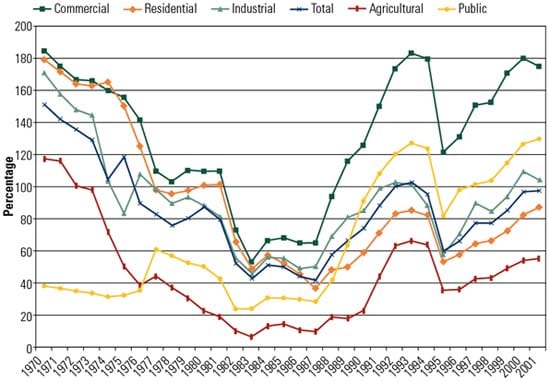

Electricity tariffs are set by the Secretaría de Hacienda (Treasury Department). As the tariff is set so close to the government, it is also very difficult to lower or cancel this tariff due to the political cost associated with doing so. As Figure 1 shows, these tariffs have fluctuated with the price of oil anti-cyclically. The prices for household and for agricultural use, both of which directly affect voters, are the lowest.

1. Mexican electricity rates as a percentage of U.S. rates. Source: CFE-SENER

Potential Reform

While investment opportunities in the energy sector may be limited by the role of the large state monopolies (CFE and PEMEX), there remain opportunities to invest — providing that the investor understands the Mexican market.

Diana Sasse and Alberto Silva, lawyers at Goodrich, Riquelme y Asociados, a full-service legal firm with more than 75 years of experience, argue that although Mexico may have a more closed environment in both electricity generation and oil and gas, the multinational companies that come to Mexico understand this and also see that there nevertheless is money to be made in Mexico.

Guilarte, one of the leading authorities on the Mexican energy sector, as noted above, concurs: "There are still opportunities in Mexico. Sometimes the press overlooks the positive projections and great potential of Mexico in the near future, especially in business, which can be quite profitable. Mexico is a modern nation and one of the best choices to invest in Latin America." He then goes on to specify that the CFE is consistently changing and improving facilities, so despite the regulatory restraints and the absence of a solid reform plan on the table, he remains firmly optimistic.

Despite arguments that the state-owned CFE would struggle to compete in terms of efficiencies with world-leading energy companies and deters private investment, the reality is that, as is the case with PEMEX, there is very little chance of changes being made to the constitution to enable much more private competition in the near future. This is a topic that is considered too dangerous for an administration even to discuss due to the political fallout that such moves would undoubtedly entail. The last major attempt was made in 1999 by President Ernesto Zedillo, who backed a radical bill attempting to privatize the majority of plants and unbundle the sector. Both this and the later attempt by President Vicente Fox to introduce legislation specifying that electricity was a commodity and not a public good, failed and caused considerable political damage to their instigators’ political careers.

There are, of course, voices calling for reform. Juan Carlos Machorro, partner at Santamarina y Steta, speaking in a personal capacity, argues, "Ideally reform of the electricity sector should be part of a deeper structural reform in Mexico. This package should include reform to both the electricity and the oil and gas sectors. Mexico should allow for more direct and free access for the private sector. If we can’t have direct involvement of the private sector within the market, we should at least have increased internal competition, such as splitting up the CFE into regional bodies. This would still be nationally owned, but would add elements of competition and certain elements which it currently lacks such as efficiency and transparency."

Adrián Escofet, consultant at Alesco Consultores, which offers strategic advice to both national and international players wishing to enter the energy market, advises that the CFE will continue to be the dominant force in electricity generation in Mexico in the near future and that anyone who wishes to come into the Mexican market must understand this. Any reform that allows the private sector further market access will not result in the CFE simply disappearing; it is too strong and entrenched for this to take place. It will remain the largest player in the generation market. An addition of private sector players could reduce the necessity of the state to invest in energy generation; however, it is unlikely that it would result in a lower cost for the end consumer.

Escofet’s father, Alberto Escofet, a former director general at the CFE as well as a government minister, argues for the creation of merchant plants. These merchant plants would be privately owned and operated and, rather than have long-term PPAs, they could compete on a free market, only operating when they could compete on price.

Alberto Escofet, CEO, Alesco Consultores; former undersecretary of energy and CEO of Luz y Fuerza del Centro and the CFE

Alternatively, Eduardo Andrade, corporate director for Latin America of Iberdrola, one of the largest players in the IPP market, argues, "I wouldn’t agree with the need for radical reform to this system. It provides a cheap way of financing projects for Mexico while providing the private sector with a role."

At the time of writing, there is no plan for serious reform of the electricity sector. President Felipe Calderón’s loss of a majority in parliament means that it relies on the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI) to pass legislation, and the PRI remains close to the CFE (and SUTERM, the union of the CFE) and is unlikely to back radical changes to the status quo.

— Written and researched by Clotilde Bonetto ([email protected]) and Mark Storry ([email protected]) of Global Business Reports.