German Giants Swap Assets and Reshape Energy Sector

Germany’s electricity sector faced a renewed, violent shakeup in March as two of its biggest utilities, E.ON and RWE, announced a complex asset exchange that experts said points to the death of the integrated model.

The deal announced on March 11 will result in E.ON selling its renewable business to RWE in exchange for RWE’s network and retail business. It will be undertaken in steps. First, E.ON will acquire RWE’s 76.8% stake in Innogy—a renewables company created in April 2016 as RWE spun off its renewables, retail, and grid businesses—and RWE will pay E.ON €1.5 billion to take on Innogy’s renewables business, along with E.ON’s minority stakes in two RWE nuclear plants (Emsland and Gundremmingen), Innogy’s gas storage business, and Innogy’s participation in hydro-rich Austrian energy utility Kelag. If the transaction clears antitrust and regulatory approvals and closes by the end of 2019, the deal is expected to create two more-robust energy companies “with a stronger entrepreneurial core,” as E.ON CEO Johannes Teyssen put it.

Both companies will be headquartered in Essen. E.ON will focus on digitized network and customer-oriented solutions, intensifying efforts to roll out charging networks for e-mobility and smart grids. RWE, on the other hand, will add an 8-GW renewables portfolio to conventional assets of about 46 GW, which will make it a European wind behemoth and offer it more prospects for growth.

Stricken by a series of disruptions, including Germany’s 2011 decision to phase out all its nuclear power plants by 2022 in response to the Fukushima disaster, and the ensuing Energiewende—the energy transition that boosted renewables growth through subsidies and sent wholesale power prices tumbling—both companies have already attempted restructuring to stay profitable. In 2016, E.ON spun off its conventional generation business in a new company, Uniper, while keeping its distribution grids, renewables businesses, and retail solutions. That year, RWE also split its business, retaining conventional generation, but spinning off renewables, distributed grids, and retail businesses to Innogy.

The recent rejiggering of their separate focuses is a direct effort to tackle renewed disruptions heralded by decentralization and increasing competition. Germany’s power markets continue to evolve in tandem with supply shifts as a result of Energiewende. In July 2016, the government adopted electricity market rules to help flexible supply, flexible demand, and energy storage compete with conventional generation—one of the biggest market reforms of its electricity market since deregulation in the 1990s.

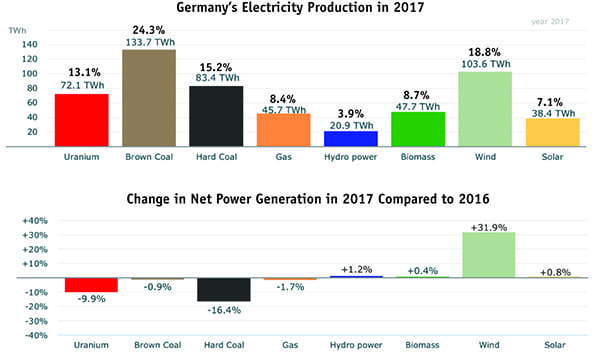

However, coal generation margins under current market conditions have fallen to record lows, and the outlook doesn’t look promising. According to S&P Global Platts data, the clean dark spread—a measure of coal plant profitability calculated as the difference between the baseload power price and the cost of coal needed to produce it—for a 35% efficient coal unit for 2019 is now below –€2/MWh. Hard coal plants are struggling in an environment characterized by low baseload power prices. In 2017, annual hard coal generation output fell 16% compared to 2016, squeezed by rising renewables (Figure 1).

Coal closure announcements keep mounting. On March 2, for example, German coal generator Enervie said it would close the 310-MW Werdohl-Elverlingsen unit—a 1982-built plant in North Rhine-Westphalia that ran only 780 hours last year—by month’s end. On the same day, German generator STEAG filed a legally binding notice with the German Federal Network Agency (BNetzA) to permanently shutter both units at its 507-MW Lünen hard coal–fired power plant by March 2019 (Figure 2). STEAG cited a “persistently difficult marketing environment,” owing to low wholesale prices that “is worsening the profitability of the plants,” for its decision. The company noted it would be forced by market conditions to temporarily take both Lünen Unit 7 and the MKV plant in Völklingen, Saarland, offline for six months beginning in April this year and next year. In March 2017, STEAG shuttered the West 1 and 2 in Voerde, and last summer it took offline Herne 3 in North Rhine-Westphalia.

However, Joachim Rumstadt, chair of STEAG’s Board of Management, noted coal economics weren’t bad throughout the country. “We see good prospects for our efficient power plants in the Ruhr area,” which is a large urban region in North Rhine-Westphalia, he said. Meanwhile, optimism was on the horizon starting in 2022, when Germany completes its nuclear phase-out. “We expect the economic environment to improve significantly after the phase-out of nuclear energy,” he said.

Rolf Martin Schmitz, CEO of RWE, too, sees value in holding on to generation assets, though he noted in early March that renewables are poised to play a sizable role when they evolve away from regulated subsidies and toward a “normal” competitive market. “Significant size is crucial for success in this future-orientated business,” he noted. “At the same time, security of supply remains the beating heart of any future-proofed industrial society.”

For now, Germany’s government appears confident that free price formation on the wholesale electricity market will ensure investment and reliability. Still, it has moved to provide backstop measures, recently establishing a new, 2-GW capacity reserve, strictly separated from the electricity market, to provide an additional safety net for “unforeseeable events.” This February, the European Commission approved the capacity reserve under state-aid rules, and the German government swiftly put rules in place for the reserve to be auctioned under three two-year contracting periods from 2019 to 2025. The first contracting phase is to begin on October 1, 2019. The minimum price paid by suppliers for the reserve is €20/MWh. By comparison, the average wholesale price on the day-ahead market stood at €34/MWh in 2017.

Under the 2016 reforms, the government also agreed with utilities to keep 2.7 GW of inefficient brown coal capacity mothballed for four years as a “very last resort” emergency standby reserve.

—Sonal Patel is a POWER associate editor.