As a U.S. Business, Nuclear Power Stinks

Regardless of one’s views of the social values of nuclear power — compelling cases can be made all around — as a business proposition nuclear stinks.

The latest evidence comes from the giant Japanese conglomerate Toshiba, which saw a third of its market value vanish in two days of trading (20% in one day, a free-fall stopped only by a limit to trading losses imposed by the Japanese stock market). Credit rating agencies promptly downgraded the company’s debt.

Toshiba’s stock crash was a result of billions in reported losses from its Westinghouse Electric subsidiary and Westinghouse’s ruinous investment last year in nuclear engineering and construction behemoth CB&I Stone & Webster, itself the product of an ill-fated merger. Toshiba’s nuclear business has been hemorrhaging money at its U.S. construction projects in Georgia and South Carolina. Westinghouse is years behind schedule and billions of dollars over budget at its two construction projects: Southern’s Vogtle and Scana Corp.’s Summer units, a total of four Westinghouse AP1000 reactors under construction. Toshiba faces the possibility that its nuclear troubles will lead the company to a negative net worth.

My colleague Aaron Larson describes the gory business details well. The bottom line is that Westinghouse threatens to bring Toshiba to its financial knees, although the firm is too large to fail entirely. It may well require a Japanese government bailout.

Then there is France’s Areva, which has been bleeding red ink for more than a decade and would have expired but for its French government owners, and a recent bailout. The company is far behind schedule and vastly over budget on construction projects in Finland and France. Late last year, discovery of quality control problems in carbon steel forgings from Areva’s Le Creusot Forge shocked the company. The allegations closed 20 of France’s 58 operating reactors, which also could jeopardize regulatory approval for extended operation at the aging plants.

In late December reports surfaced that Areva employees for decades hid problems in reactor parts it manufactured at Le Creusot Forge. Inspectors from the U.S., France,

China, and the U.K. descended on Areva to examine records and investigate the allegations. “I’m concerned that there keep being more and more problems unveiled,” Kerri Kavanagh, who leads the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s unit inspecting Le Creusot, told the Wall Street Journal.

The business case for existing nukes in the U.S. is also ominous. Just last week, an Ohio newspaper reported that Akron-based FirstEnergy will close or sell its long-troubled, 900-MW Davis-Besse nuclear unit this year or next, without counting on a state bailout. “We have made our decision that over the next 12 to 18 months we’re going to exit competitive generation and become a fully regulated company,” CEO Chuck Jones said. “We are not going to wait on those states to decide what they are going to do there.” This comes on top of multiple closings of U.S. nukes unable to compete in competitive markets in recent years, state subsidies in Illinois and New York to keep uneconomic plants open, and threats of even more shutdowns.

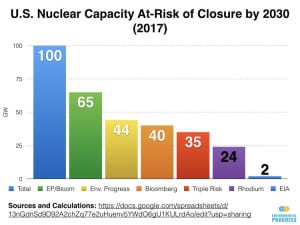

At the same time as the Davis-Besse warning, Environmental Progress, a pro-nuclear group, released an analysis that concluded that a quarter to two-thirds of operating U.S. nuclear plants could face premature closure. If it weren’t for actions by state governments in Illinois and New York, the picture would look worse.

The Environmental Progress analysis counts 35 GW of nuclear capacity as at “triple risk” because “they are in deregulated markets, uneconomical (according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance) and up for relicensing before the end of 2030.” Facing greatest jeopardy for early closure? D.C. Cook in Michigan, Seabrook in New Hampshire, Millstone in Connecticut, and Davis-Besse in Ohio.