Analysts still see multi-year deficits in U.S. transformer supply, even as equipment manufacturers invest billions in new factories and advanced manufacturing processes. But some brokers suggest there is no real shortage and that, if there is a crisis, it stems from procurement blinders.

The electrical transformer “shortage” seems to have become the defining supply chain story of the 2020s, and it has factored into utility capital plans, renewable deployment timelines, and even how grid resilience is discussed at the policy level. As POWER reported in 2024, over the past few years, what started as a squeeze has gradually morphed into a crisis, furnished by years of underinvestment in domestic manufacturing, a sudden surge in post-pandemic construction and electrification, and volatility in grain-oriented electrical steel (GOES) and copper markets, which steadily pushed lead times for large power and generator step-up (GSU) transformers beyond historical norms.

At POWER’s Experience POWER conference in October 2025, concerns remained centered on procurement of the critical components, which are used to step voltage up for transmission, step it back down for safe distribution, and protect every major interface between generation, the bulk grid, and end-use systems.

Utilities, prominently, have begun treating early transformer and switchgear procurement as a competitive lever in an era of accelerated build timelines to accommodate large new loads such as data centers, while engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) firms report being forced to redesign schedules, reorder work sequences, and lock in equipment earlier than ever as access to scarce grid components increasingly determines which projects can advance and which are pushed into multi-year limbo. In 2025, several consulting firm assessments continued to warn of persistent transformer shortages and an overstretched supply chain. However, some market participants go further, arguing that there is no real shortage and that procurement practices—not manufacturing capacity—are the bottleneck.

The Shortage by the Numbers

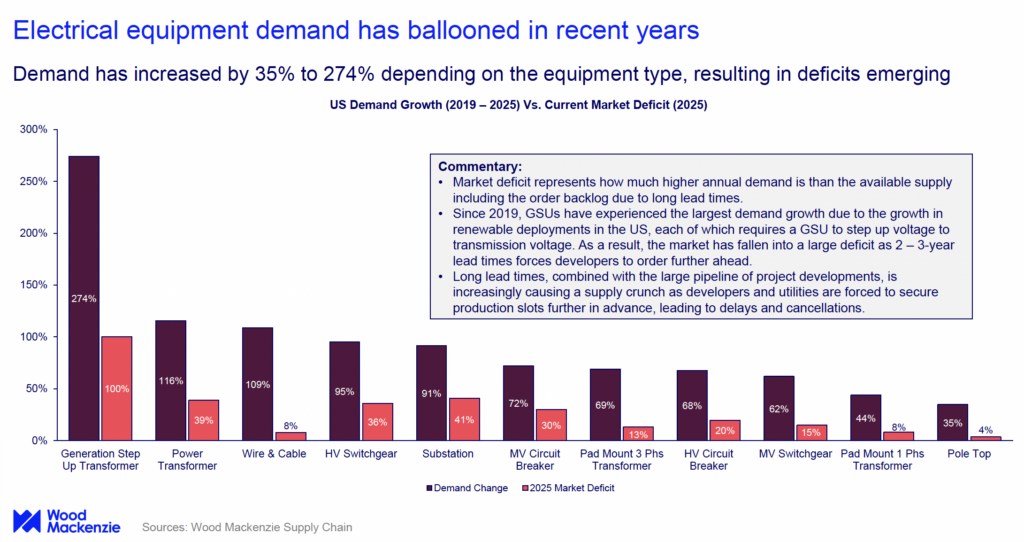

In an August 2025 analysis, consulting firm Wood Mackenzie warned that the U.S. transformer market remains structurally out of balance, and that demand continues to outpace any realistic near-term increase in manufacturing capacity. The firm noted that power-transformer demand has risen 119% since 2019, and distribution-transformer demand is up 34%, driven by faster-than-expected load growth, an expanding clean-energy pipeline, and a wave of end-of-life replacements. One of the summary findings put it bluntly: “Supply shortage persists as demand growth remains robust.”

Aging infrastructure is a major contributor, the report notes. According to the analysis, more than half of U.S. distribution transformers—roughly 40 million units—are already beyond their expected service life, adding a steady replacement burden on top of rising new-build requirements. That cumulative pressure helps explain the persistent deficits Wood Mackenzie models for 2025: an estimated 30% shortfall for power transformers and 10% for distribution units across the national fleet.

However, the tightening is most severe in higher-voltage classes. Since 2019, demand for generator step-up units has grown 274%, and substation power transformers are up 116%, reflecting both grid modernization needs and the acceleration of large-scale generation and data center development. Lead times mirror that imbalance. While distribution transformer availability has improved, large units remain locked above two years, with power transformers averaging 128 weeks and GSUs 144 weeks in WoodMac’s second quarter 2025 survey. Meanwhile, costs have also climbed. Since 2019, unit prices have increased 77% for power transformers and 45% for GSUs, with some classes of distribution transformers rising as much as 95%.

|

|

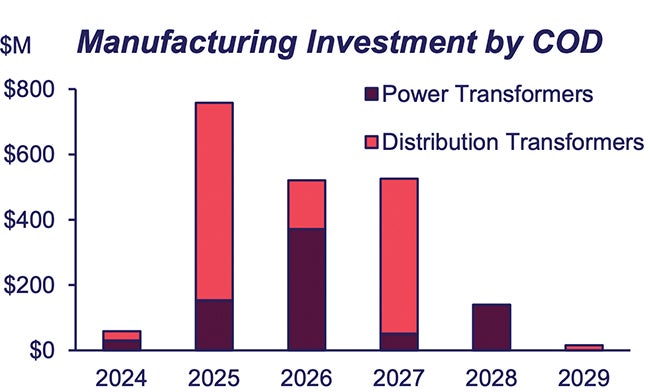

1. Market impacts identified by Wood Mackenzie include escalating competition for factory slots, rising equipment prices, and multi-year lead times for large transformers—conditions that have triggered nearly $1.8 billion in new North American manufacturing investments, shown here by expected commercial operation date (COD). Courtesy: Wood Mackenzie, Making the Connection: Meeting the Electric T&D Supply Chain Challenge (Sept. 2025) |

For now, even with nearly $1.8 billion in announced North American manufacturing expansions (Figure 1), Wood Mackenzie expects that while some deficits may ease, the “pad-mount three-phase transformer shortage is likely to worsen due to surging industrial demand from data centers, manufacturing facilities, and EV [electric vehicle] charging infrastructure.” The report concludes that without intervention, “extended lead times and elevated costs will become the new normal, potentially derailing grid modernization efforts.”

A Solid Effort to Expand Manufacturing

Still, the severity and duration of the transformer crunch appear to have finally forced a reckoning across the supply chain, prompting the most significant manufacturing buildout the sector has seen in decades. As a historically low-margin, capital-intensive industry, transformer manufacturing is responding to sustained demand growth and a policy environment, despite its vacillation, that prioritizes grid modernization and domestic manufacturing. Over the past year, policy signals around transformer manufacturing have been notably mixed but potentially disruptive.

On one hand, Washington has doubled down on trade measures: copper now faces tariffs of up to 50%, Section 232 steel and aluminum duties have been expanded to hundreds of additional tariff lines, and new “Liberation Day”–style actions have ratcheted up rates on imports from key suppliers such as Brazil, India, and China.

Those moves raise costs for both imported transformers and domestic manufacturers that rely on foreign electrical steel, transformer cores, and copper wire. At the same time, a budget package widely dubbed the “One Big Beautiful Bill” has begun phasing down investment and production tax credits for renewables while tightening foreign‑entity‑of‑concern (FEOC) rules, effectively curbing the use of Chinese‑linked transformer content in projects that depend on federal incentives. But, countering those headwinds, federal and state economic development agencies have leaned into reshoring with tax breaks, loan guarantees, and site selection support for new plants in Virginia, the Carolinas, Tennessee, and elsewhere, signaling that long‑term policy risk now favors North American manufacturing—if companies can navigate the near‑term tariff and demand volatility.

|

|

2. Hitachi Energy’s Varennes, Quebec, facility, shown here in a post-expansion rendering, is undergoing a CA$270 million buildout to nearly triple output of large power transformers amid surging demand. Courtesy: Hitachi Energy |

Since 2023, manufacturers have committed nearly $2 billion to new or expanded transformer capacity, spanning everything from pole-mount units to 765-kV transmission-class equipment. Hitachi Energy (Figure 2) leads the surge with more than $1 billion in continental investments, including a $457 million facility in South Boston, Virginia—which is set to become the nation’s largest large power transformer plant by 2028—and a $106 million expansion in Alamo, Tennessee, focused on critical components. Siemens Energy is building its first U.S. large power transformer plant in Charlotte, North Carolina, a $150 million project expected to begin production in early 2027. Eaton has committed $340 million to a three-phase transformer facility in South Carolina, also targeting a 2027 start.

Mid-sized and specialized manufacturers are scaling aggressively as well. Prolec GE is investing more than $300 million across new and expanded sites, including a medium-power facility in Goldsboro, North Carolina, and additional pad-mount capacity in Louisiana and Mexico. Virginia Transformer Corp. is undertaking a $40 million expansion in Georgia to boost output by 70%, while WEG is adding transformer capacity in Missouri. Distribution-class expansions include ERMCO’s $70 million-plus investments in Tennessee and Wisconsin, Central Moloney’s new $50 million Florida plant, and MGM Transformer Co.’s 430,000-square-foot facility in Waco, Texas. Even HD Hyundai Electric is enlarging its Alabama footprint, aiming to increase U.S. production by 30% by 2026.

The Transformer Shortage Is Systemic, Not IsolatedWhile transformers draw the most attention, the transformer shortage is really a transmission and distribution (T&D) equipment shortage. Demand across nearly every major category of electrical infrastructure has surged since 2019—by 35% to 274% depending on the equipment type, according to Making the Connection: Meeting the Electric T&D Supply Chain Challenge, a September 2025 report co-authored by Wood Mackenzie and American Clean Power. Generation step-up transformers appear to be the most stressed, but high-voltage (HV) switchgear and medium-voltage (MV) circuit breakers are running short, too. Lead times reflect the pressure: switchgear averaged 44 weeks in Q2 2025, while pad-mount transformers, reclosers, and wire and cable all recorded quarterly increases. Prices for these components are also climbing: circuit breakers have jumped 47% since 2021, with medium-voltage switchgear up 50%, as multiple markets compete for scarce manufacturing slots. The underlying demand drivers remain relentless. Data center expansion, manufacturing construction spending increases of 96% over three years, and a pipeline of renewables projects all push competing demands on the same equipment base. Aging infrastructure adds to the burden: roughly 55% of in-service distribution transformers are more than 33 years old and approaching end-of-life, triggering replacement demand on top of new construction. For now, tariffs appear to be making matters worse. Evolving trade policy is expected to put “additional upward pressure on both imported and domestically produced equipment,” according to the report, even as expanded Section 232 steel and aluminum duties inflate costs for U.S.-made components. One result may be that utilities and developers cannot solve the constraint by sourcing around one bottleneck. A project team securing transformers on a 12-month timeline may still find switchgear, breakers, or wire in equally tight supply, the report suggests.

|

Is There Really a Shortage?

Against the prevailing narrative of deficits, long lead times, and constrained factory capacity, some market participants argue that the shortage is overstated. One of the most forceful voices is Patrick Tarver, owner of Bolt Electrical LLC, who describes his firm as “a middleman for different transformer companies throughout the U.S and the world and Mexico.” He characterizes the company as “small, personnel-wise; midsize, money-wise,” and says he serves customers “anywhere in the world that you need to transform.”

Tarver’s central claim challenges the core assumption of the transformer crisis. “There is not a shortage,” he said when asked about the widely cited 30% supply deficit. He asserted that for a standard substation power transformer, once “the initial engineering drawings were approved,” he could have a unit “delivered within 12 to 14 months.” He added that this applies to “all voltage classes” and emphasized, “I’m not the only person that can do this.”

On pricing, Tarver said he typically adds 12% to 15% to factory cost for his services, including staying involved through warranty support. Even with that margin, he argued, “our prices are a lot cheaper than the big four manufacturers, the large manufacturers.” When discussing materials constraints, he rejected much of the industry’s framing: “It’s all exaggerated to drive pricing. I’m telling you that we can get the supplies they need, but they don’t ask.”

For Tarver, the real constraint is access to decision-makers. He contends that the bottleneck lies beyond factory output and more in the structure of utility and EPC procurement, including layers of qualification rules, vendor lists, and internal hierarchies that prevent alternative suppliers from ever reaching the people who could authorize a different approach. In his view, utilities default to familiar equipment manufacturers because their internal processes are designed in ways that reinforce existing relationships rather than evaluate whether faster or more cost-effective options might be available.

If that dynamic is as widespread as he suggests, it implies a supply environment more varied than headline lead times indicate. But it remains difficult to validate without broader engagement from manufacturers and buyers: large power transformers are highly customized, heavily regulated assets, and many utilities face legitimate constraints tied to standards, testing protocols, cybersecurity requirements, and domestic-content rules.

—Sonal Patel is a POWER senior editor (@sonalcpatel, @POWERmagazine).