Chernobyl: Twenty-Five Years of Wormwood

Twenty-five years ago last month, engineers and technicians were running low-power tests at the 1,000-MW Reactor No. 4 of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant outside Kiev. They quickly, inexplicably, lost control of the light-water-cooled, graphite-moderated reactor. In an instant, the critical chain reaction flared out of control. The plant exploded like a small, dirty bomb, the graphite caught fire, and the worst catastrophe in civilian nuclear power was under way.

The immediate fallout, using the term broadly, not only killed brave first responders—who faced brutal radiation doses as they flew helicopters over the smoking carcass to drop sand, clay, boron, and lead to suffocate the beast—but also a photographer who documented their bravery and plant workers unlucky to be working the early morning shift when the unit went wild.

How many died? Former USSR President Mikhail Gorbachev was running the Soviet government when the reactor exploded. Writing in the March-April 2011 issue of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Gorbachev’s estimate 25 years later remains imprecise: “Some 50 workers died fighting the fire and reactor core meltdown, and another 4,000 or more deaths may eventually be shown to have resulted from radioactive releases. The radiation dosage at the power plant during the accident has been estimated at over 20,000 roentgens per hour, about 40 times the estimated lethal dosage, and the World Health Organization identified 237 workers with Acute Radiation Sickness.”

|

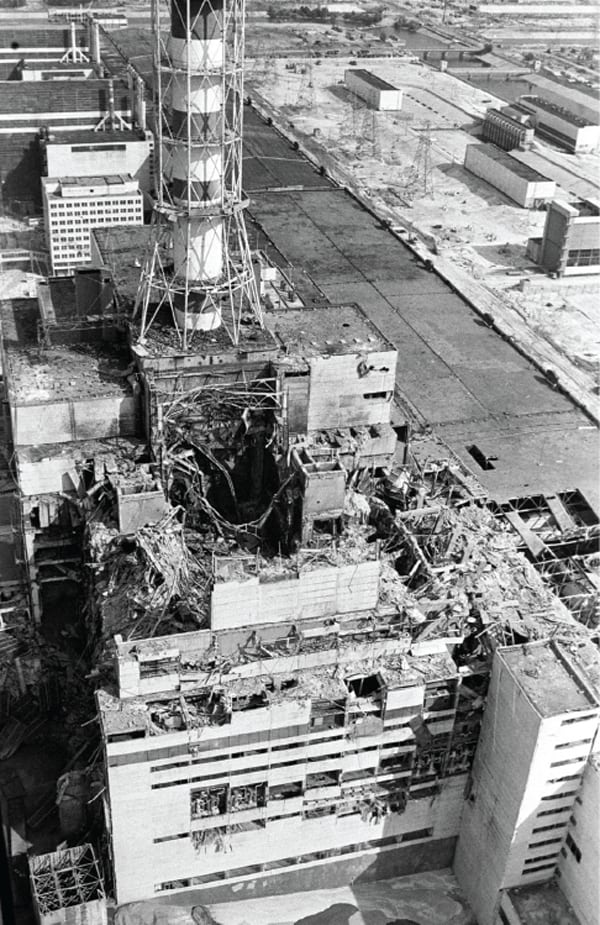

| 1. Days after. This is an aerial view of Reactor No. 4 at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant just days after it caught fire and exploded on April 26, 1986, sending a radioactive cloud of dust over Ukraine, Belarus, Russia, and other parts of Europe. Courtesy: Reuters |

|

| 2. Buried trouble. A concrete sarcophagus was erected by December 1986 to seal off the reactor and halt the further release of radiation into the atmosphere. The heat inside the reactor remains over 200C today, and the concrete structure is showing signs of stress. At the time of the explosion, only 3% of the nuclear material in the plant was expelled, leaving about 216 tons of uranium and plutonium buried in the reactor. Courtesy: Reuters |

The Accident was Local…

A radioactive cloud spread westward over much of Europe. For weeks, the release fell over cities and fields. The atomic industry coined a euphemism to describe the event: “rapid disassembly of the core.”

Chernobyl dominated newspaper, radio, and television news. In countries with nuclear power programs, a political tussle broke out among those who ran—and advocated—nuclear plants and those who sought to shut them down. Opponents of nuclear power sought to make Chernobyl a symbol of the evils of the atom. Proponents stressed the inherently flawed, one-off design of the RBMK plants, unlike the West’s typically water-cooled and -moderated plants.

There was satisfaction for the supporters of civilian atomic power plants that the machines the Soviets provided to their captive satellite countries were similar to, and perhaps stolen from, modern U.S. and European light water reactors. Western engineers, with tongue in cheek, often described the Soviet VVER designs as “Eastinghouse” reactors. The Russians were reluctant to supply their conquered Warsaw Pact allies with units that could make both electricity and weapons-grade plutonium, fearing that Poles and Czechs and Hungarians might get ideas about turning plowshares into swords.

Predictably, the Chernobyl disaster had cultural echoes. In 1988, Marvel Comics produced a “Meltdown” series of comic books, featuring the superhero Wolverine and using the Chernobyl accident a plot device. In 2005, crime writer Martin Cruz Smith, author of the best-selling Gorky Park, wrote Wolves Eat Dogs, which also featured Chernobyl in the back story. For those interested in nuclear energy history, nuclear accidents have figured in popular culture at least since the 1954 Castle Bravo H-bomb test on Bikini Atoll. That incident accidentally exposed a Japanese fishing boat, the Fukuryu Maru, sickening all 23 crew members, one of whom died within seven months of radiation sickness. That episode set off a firestorm of controversy in Japan and inspired the Godzilla monster movies. The 1959 French movie Hiroshima Mon Amour, dealing with the lasting and evanescent qualities of memory, started a motion picture genre known as “new wave.” In 1979, The China Syndrome, starring Jane Fonda, Jack Lemmon, and Michael Douglas, eerily preceded the Three Mile Island accident.

… But Was Felt Globally

Chernobyl ultimately had little impact on worldwide nuclear development. The unique design of the Russian reactors meant that the event had few specific implications for most of the designs employed then and now in the rest of the world. Economics and national politics continued to drive nuclear power development, as they had before Chernobyl.

But the Ukrainian atomic explosion did have important impacts on attitudes within the industry, much as the March 1979 Three Mile Island (TMI) accident had reinforced the message that safety in nuclear power is Job 1. In the U.S., TMI resulted in the formation in December 1979 of the Institute for Nuclear Power Operations (INPO), the industry’s self-policing watchdog. That organization was the forerunner of a dramatic turnaround in performance at U.S. nuclear plants.

In 1989, in the aftermath of Chernobyl, the world’s nuclear nations formed the World Association of Nuclear Operators (WANO). Both INPO and WANO were largely the fruits of efforts made by the late William States Lee III, legendary CEO of Duke Power who worked at Duke for four decades. Bill Lee often said that both TMI and Chernobyl were key events in improving the safety and performance record of nuclear power.

Chernobyl, by many accounts, also played an important role in the demise of the USSR, by undermining much of the mythology behind communist ideology. One of the tenets of Russia’s Bolshevik version of communism was the idea of the “new Soviet man.” This was a doctrine of the perfectibility of mankind, a belief that social and political forces could mold individual behavior. Here’s how Leon Trotsky put it in his 1924 book Literature and Revolution: “Man will make it his purpose to master his own feelings, to raise his instincts to the heights of consciousness, to make them transparent, to extend the wires of his will into hidden recesses, and thereby to raise himself to a new plane, to create a higher social biologic type, or, if you please, a superman.”

One corollary of the “new Soviet man” doctrine was a religious fealty to technology. In that religious pantheon, electricity ranked high. One of the early slogans of Bolshevism reads: “Communism equals Soviet power plus electrification of the entire country.” In his fine 2000 book Red Atom, historian Paul Josephson wrote that in the USSR, technology “had become a panacea for the great economic, social and political challenges facing the nation as it embarked of the path of modernization. Many peasants and workers embraced the new technology, naming their sons ‘Tractor’ ( Traktor) their daughters ‘Electrification’ ( Elektrifikatsiia) or ‘Forge’ ( Domna).”

Chernobyl dashed that technology worship and the concept of the perfectibility of Soviet man. But by April 1986, the foundation of Soviet communism had already begun to crack. Gorbachev had contributed with his policy of “glasnost” or openness, implemented before Chernobyl as an antidote to rampant corruption. Among the fruits of glasnost was an invigorated Russian press that began highlighting the major problems of the Soviet Union, including alcoholism, malingering, food shortages, and environmental destruction.

The events of late April 1986 and their aftermath administered a stern test to glasnost. At first, the Soviets retreated to form, dissembling and covering up events in Ukraine. But soon, probably under Gorbachev’s orders, the Soviet government came clean about the accident. By September, the USSR delivered a full report on the accident to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in Vienna, acknowledging terrible errors in operating the plant. Time magazine described the Soviet accident report as “one of the more startling examples of a new Soviet openness.”

|

| 3. Today. This photograph of the sarcophagus covering the damaged Reactor No. 4 was taken on February 24, 2011. Belarus, Ukraine, and Russia will mark the 25th anniversary of the nuclear reactor explosion in Chernobyl, the place where the world’s worst civil nuclear accident took place, on April 26. Courtesy: Reuters |

In a Chernobyl 20th anniversary assessment, the IAEA commented, “Under heavy pressure from the West to provide open information on the accident, Gorbachev imposed full glasnost, thereby annihilating one of the strongest pillars of the Soviet regime. That regime fell apart soon after. Chernobyl was a major catalyst in triggering the chain reaction of events that would soon lead to the disintegration of the Soviet Union.” (For more on the event and its aftermath, see the multimedia page assembled by the IAEA at http://www.iaea.org/newscenter/focus/chernobyl/.)

A New Perspective

Now, 25 years later, what is one to make of the bitterness of Chernobyl and what it begat? The IAEA’s conclusion of 2006 remains valid. The agency observed that “the public seems to have gradually changed its perception of nuclear energy, against the backdrop of what is often referred to as ‘the nuclear renaissance’. This could be seen as evidence of the maturity of nuclear technology, of the adequacy of the safety culture, of effective regulations etc…. But it may also be proof of loss of memory.”

The IAEA also cautioned, “One single major accident in a power plant could—in a matter of minutes—ruin twenty years of considerable effort.”

— Kennedy Maize is a POWER contributing editor and executive editor of MANAGING POWER.