Nuclear power is emerging as a key, enabling technology for sustained human presence on the moon. With multiple countries and companies announcing ambitious lunar programs—from space research to mineral development to hotels—there is increasing global competition to establish long-term power supply and other infrastructure on the lunar surface.

Nuclear power has deep historical roots in U.S. space missions and is now central to U.S. lunar policy and goals. As international and commercial competition increases, the legal framework governing inhabitation of the moon and using its resources may be put to the test.

COMMENTARY

Historically, nuclear power has played a key role in U.S. space missions. Transit 4A, a U.S. Navy satellite launched in 1961, was the first spacecraft to use a nuclear power source. Later, the Pioneer, Voyager, Galileo, Ulysses, Cassini, and New Horizons space probes relied on nuclear power, as did the Mars Viking missions and subsequent Curiosity and Perseverance rovers.

Each of these missions employed Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generators (RTGs) that convert heat produced from the radioactive decay of Plutonium-238 into electricity. RTGs provide long-lived, reliable power and enable missions to operate far from the Sun where solar power supplies may be inadequate for mission purposes.

The U.S. also has limited experience with fission-based nuclear reactors powering space missions. In 1965, the U.S. launched the SNAPSHOT satellite which was powered by SNAP-10A, a 500 W sodium-potassium cooled reactor. SNAPSHOT successfully demonstrated that compact reactors could provide reliable nuclear power for space missions. The former Soviet Union also launched nuclear reactor-powered space missions, including the TOPAZ I and II and BES-5 missions.

The U.S. has already used nuclear power on the moon. Multiple Apollo missions deployed Apollo Lunar Scientific Experiments Packages that were powered by RTGs to conduct a variety of scientific experiments. The RTGs used in previous missions, however, could not provide enough power to support a human habitat or mineral exploration and development activities on the moon. An inhabited base station or substantial resource development will likely require a nuclear reactor. To date, neither the U.S. nor any other country has deployed a fission-based reactor on the moon. That may change soon.

On Dec. 18, 2025, President Trump issued Executive Order 14369, “Ensuring American Space Superiority,” which declared numerous U.S. space priorities including returning Americans to the moon by 2028, establishing the initial elements of a permanent lunar outpost by 2030, and laying the foundations for lunar economic development. To enable the next century of space achievements, the order set a goal of “deploying nuclear reactors on the Moon and in orbit, including a lunar surface reactor ready for launch by 2030.”

In response to the order, NASA and the U.S. Dept. of Energy in January of this year renewed their partnership in the Fission Surface Power Program—a collaborative, interagency effort to deploy a fission-based lunar surface reactor that can provide safe, reliable, and abundant power for multi-year lunar missions.

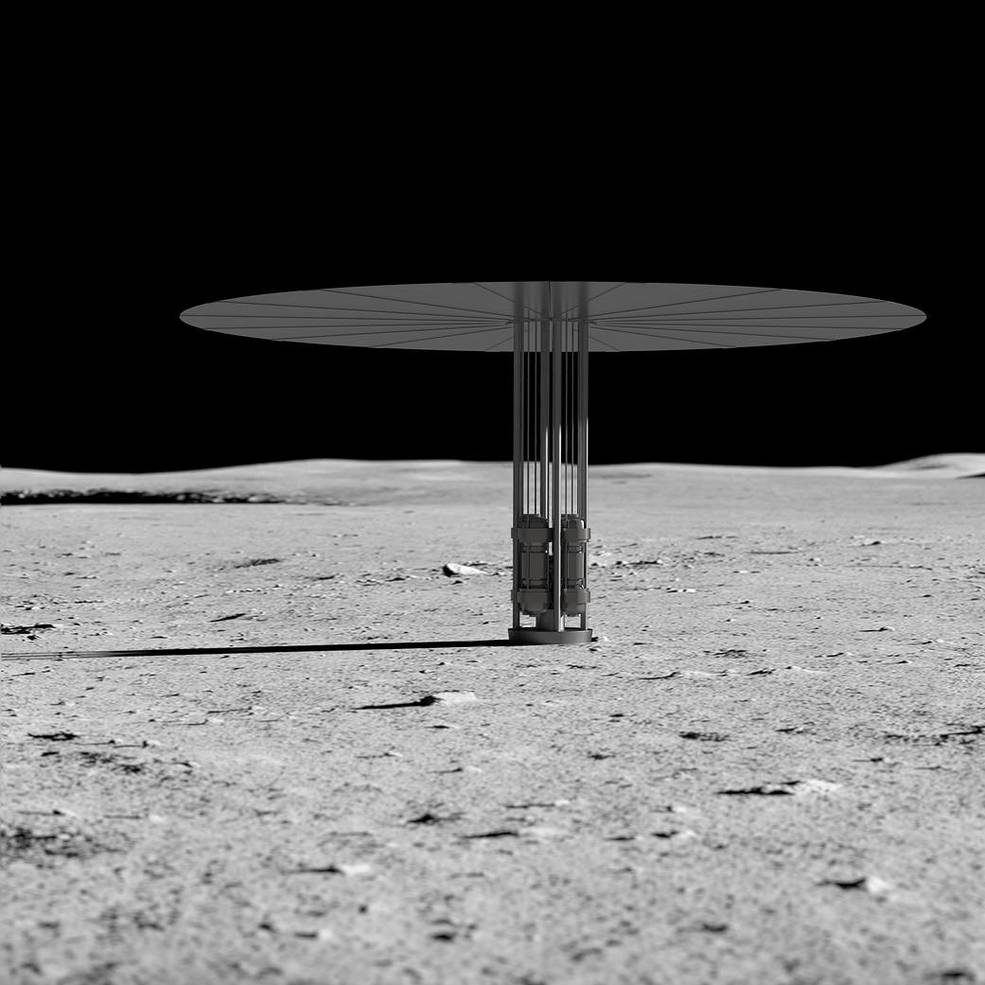

While the specific design of the reactor and the schedule for its deployment are not yet known, an August 2025 NASA Request for Information described expectations for the Fission Surface Power System: operate on the lunar surface in proximity to crewed and uncrewed lunar assets, including human-rated landers, rovers, and pressurized habitats; have a minimum power output of 100 kW(e); have a mass of less than 15 metric tons; utilize a closed Brayton cycle power conversion system (generating power by heating and cooling a mixture of helium and xenon); and be ready to launch by the first quarter of fiscal year 2030. NASA identified the 100 kW(e) system capacity as being needed to support in-situ resource utilization and in-situ manufacturing demonstrations.

NASA’s Artemis program includes collaboration with commercial partners to advance scientific discoveries and technology required to live and work on other celestial bodies. The Artemis Accords, a multilateral agreement drafted by NASA and signed by 56 states, outlines “the vision and principles for a safe, transparent environment that facilitates exploration, science, and commercial activities for all of humanity to enjoy.” The parties to the Artemis Accords intend to establish a lunar base camp, and then expand the base camp to become a more permanent moon base. Surface activities on the Moon will be supported by an orbiting platform, the Gateway, which will allow astronauts to commute between Moon orbit and the lunar surface.

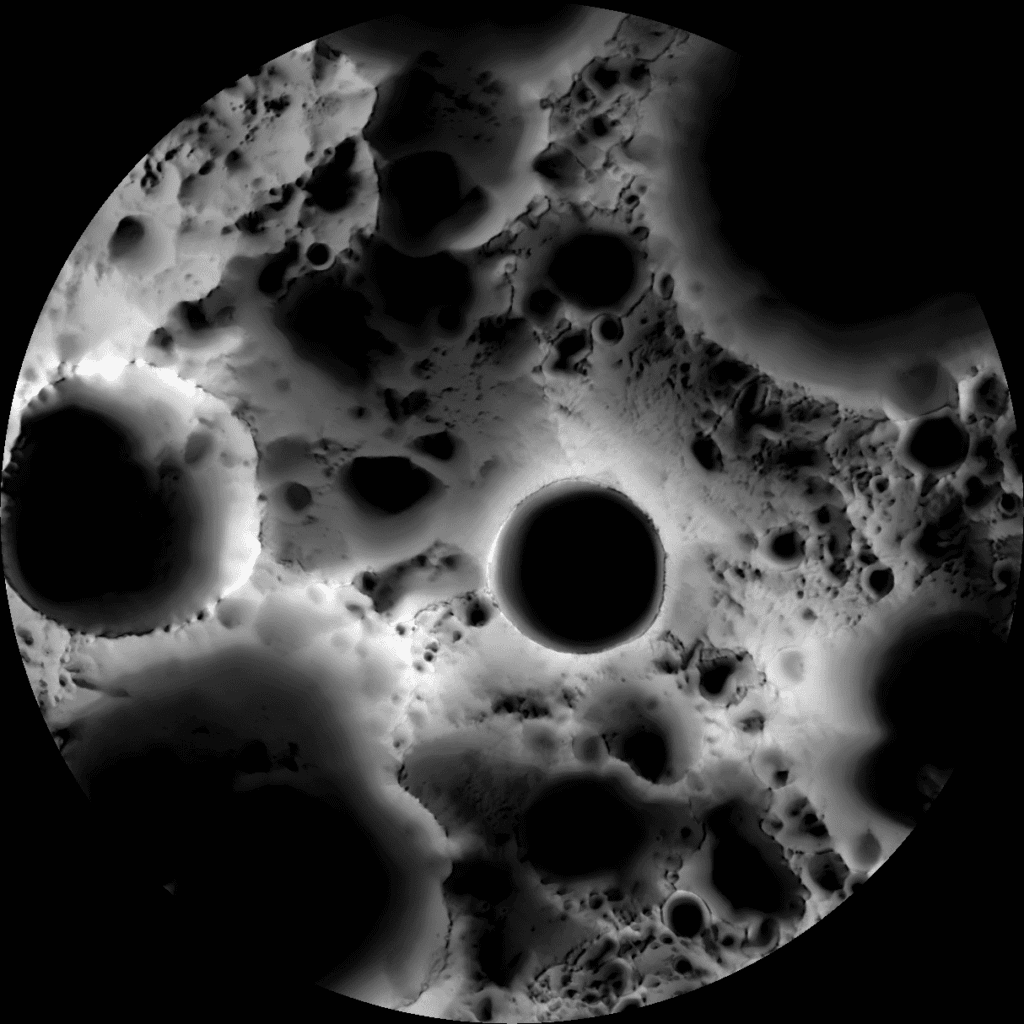

NASA intends to establish the base camp near the moon’s south pole: “Among the many things NASA must take into account in choosing a specific location are two key features: The site must bask in near continuous sunlight to power the base and moderate extreme temperature swings, and it must offer easy access to areas of complete darkness that hold water ice.”

But finding both light and access to ice can be problematic. Locating the base camp at a higher elevation will provide access to light, but the areas with lunar ice are in complete darkness. Also, the moon’s south pole region has a two-week long lunar night when temperatures can drop to -250C. A fission reactor can provide power under those conditions while solar power will struggle to meet the needs of the base camp. Nuclear power would therefore allow more flexibility in locating the Artemis base camp, and nuclear generation would facilitate both the extraction of lunar ice and process the rock holding that ice into water, oxygen, and hydrogen.

Commercial entities are already responding to this initiative. On January 15, NANO Nuclear Energy, a developer of nuclear microreactors, issued a request for information “soliciting potential commercial partner input in support of U.S. Department of Energy and NASA Lunar Surface Reactor Program.” Even more ambitiously, GRU Space, a space tourism company, announced it is taking reservations for the first hotel on the moon, which it plans to deploy by 2032.

The U.S. is not alone in its lunar nuclear ambitions. In 2024, Russia and China announced a joint effort to develop and deploy on the lunar surface a nuclear reactor by 2035 in connection with the proposed International Lunar Research Station (ILRS). The ILRS will adopt an approach similar to the Artemis Project, with research and exploration both in orbit and on the surface.

The ILRS mission will start with the establishment of a command center, including basic energy infrastructure, eventually resulting in in-situ resource utilization. As with the Artemis Project, the ILRS will be located at the lunar south pole. Separately, in December 2025, the Russian space agency Roscosmos announced a contract with aerospace company NPO Lavochkin to build a Russian lunar power plant by 2036. Given the participation of Rosatom and the Kurchatov Institute, two Russian nuclear entities, the power plant would presumably be nuclear.

The first country to successfully deploy a nuclear reactor on the lunar surface will have a power supply that would not only support a human habitat but could also help unlock the moon’s resources. In addition to gaining access to these resources, the first-mover nation could declare an exclusion zone on the lunar surface to minimize exposure to radiation. Such an exclusion zone would also advance that nation’s political and economic objectives.

Any exploration of and habitation on the moon will be regulated by existing international agreements for space and nuclear activities. The Outer Space Treaty (OST) prohibits placing nuclear weapons into orbit but does not address the peaceful use of Nuclear Power Sources (NPS). It does, however, require that states explore celestial bodies in a way that avoids harmful contamination and adverse changes to Earth’s environment.

Additionally, the Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects assigns to the launching state absolute liability for damages caused by its space objects on Earth or in flight. The United Nations has adopted nonbinding Principles Relevant to the Use of Nuclear Power Sources in Outer Space which address, among other things, NPS launch protocols, risk mitigation and safety guidelines in space, and a liability and compensation framework for damage caused by NPS-bearing space objects.

The International Atomic Energy Agency also provides a safety framework for NPS applications in outer space focusing on “protection of people and the environment in Earth’s biosphere from potential hazards associated with relevant launch, operation and end-of-service mission phases of space NPS applications.”

Much of space law has been developed to be broad and relies on “anticipatory regulation” that formulates rules for future events. The OST does not explicitly address the modern complexities of technology and economics in space like nuclear power or moon mining. For example, current treaties lack clarity on their applicability and enforceability against private entities conducting space activities, but rather rely on nation-state supervision of private companies. These ambiguities could be resolved through customary international law, new treaties, and new agreements.

States are broadly guided by existing international law when forming their domestic policies for nuclear-powered missions in space. State policies, however, do not provide a uniform interpretation of the OST because states tend to form domestic policy through self-serving interpretations of existing international laws. No existing treaties, laws, or regulations specifically address the potential issues related to operating nuclear reactors on the moon.

On Earth, radioactive materials can severely disrupt ecosystems and harm humans. Rockets with nuclear payloads can explode during launch or fall back to Earth, potentially disbursing radioactive material. This occurred in 1973, 1978, and 1982, when some of the USSR’s 32 nuclear-reactor-powered Radar Ocean Reconnaissance Satellites (RORSATs) fell back to Earth, leaving some degree of radiation on Earth or in the atmosphere—particularly, the 1978 Kosmos-954 incident that spread radioactive debris across hundreds of miles in northwestern Canada. Similar launch risks will exist when transporting nuclear reactors to the moon, and safety considerations will be important to prevent another Kosmos-954 incident.

On the moon, operating nuclear reactors can create “new environmental and operational hazards[.]” NPSs can create additional radiation concerns for humans and any other living organisms, adding to the already existing harsh radiation on the moon. This risk is further exacerbated for astronauts who may be required to perform maintenance activities on lunar nuclear reactors. There are at present no lunar specific safety protocols, cleanup obligations, or enforcement policies to hold states responsible for nuclear accidents on the moon. The outdated existing international law regime “is inadequate…especially concerning how to attribute responsibility and manage emerging risks.”

Deploying nuclear energy on the moon also presents technical challenges. Nuclear generators are heavy. Lunar temperatures are extreme. Operations may require a robust safety zone or exclusion area that precludes other use of the lunar surface.

All that said, the primary motivating force at present is not technology but rather the commitment of nations to be the first to successfully and continuously operate nuclear power on the moon to “shape the rules of the road and claim first-mover advantage.”

Both the Artemis parties and the ILRS consortium have announced their intention to use nuclear generation on the surface of the moon. These twinned promises will create a race to become the first mover, and as a result nuclear generation on the moon seems inevitable. Both Artemis and ILRS will be working over the next few years to solve the technological hurdles to a lunar nuclear facility and optimize the benefits that can be gained by deploying nuclear power in support of a sustainable moon base. The journey will continue.

—Tom Dougherty leads Womble Bond Dickinson’s Nuclear Sector Team, representing a diverse range of commercial, utility, infrastructure, and government clients in litigation, regulatory, legislative, and public policy matters. Scot Anderson is WBD’s co-office managing partner in Denver, with a background in oil, gas, and mining. Anderson advises clients on commercial transactions, including the acquisition, divestiture, and financing of natural resource projects. Madison Squibb is a law clerk at Womble Bond Dickinson and current J.D. candidate at Washburn University School of Law.

- energy security

- LEU+

- advanced nuclear reactors

- American Centrifuge Operating

- Orano

- domestic uranium enrichment

- nuclear fuel policy

- HALEU

- General Matter

- uranium enrichment

- Global Laser Enrichment

- nuclear fuel cycle

- Louisiana Energy Services

- Laser Isotope Separation Technologies

- DOE

- nuclear fuel supply chain

- NRC

- Centrus Energy