The explosive growth of cloud computing, artificial intelligence, and enterprise data storage has transformed data centers into the critical infrastructure of the digital economy. Yet their extraordinary and continuous electricity demands—often exceeding 100 megawatts per site—have made energy access and reliability the single most consequential factor in determining where these facilities are built.

Across the U.S., an unmistakable pattern has emerged: developers are increasingly clustering data centers near abundant natural gas resources. This proximity offers more than just convenience. It provides access to stable, dispatchable energy and leverages existing pipeline and transmission infrastructure already optimized for large-scale industrial use. Still, while this strategy delivers operational and economic advantages, it also introduces a complex legal terrain encompassing energy regulation, environmental compliance, land use, and sophisticated contracting.

Strategic Logic of Locating Near Natural Gas

Natural gas remains the dominant source of electricity generation in the U.S., supplying more than 40% of total power. Its reliability, scalability, and cost predictability make it uniquely suited to the uninterrupted, high-density energy loads demanded by modern data centers.

For developers, the rationale is straightforward:

- Energy Security: Data centers require firm, 24/7 baseload generation, something intermittent renewables cannot yet fully provide.

- Infrastructure Efficiency: Locating near pipelines, gas processing plants, or combined-cycle generation facilities reduces interconnection costs and regulatory delays.

- Transitional Sustainability: Natural gas produces roughly half the carbon emissions of coal, allowing operators to pursue decarbonization goals without compromising uptime.

These factors have fueled intense competition for development sites in gas-rich regions, particularly where existing energy infrastructure and favorable regulatory frameworks intersect with economic incentives.

The pros and cons of the country’s regional hubs of opportunity include:

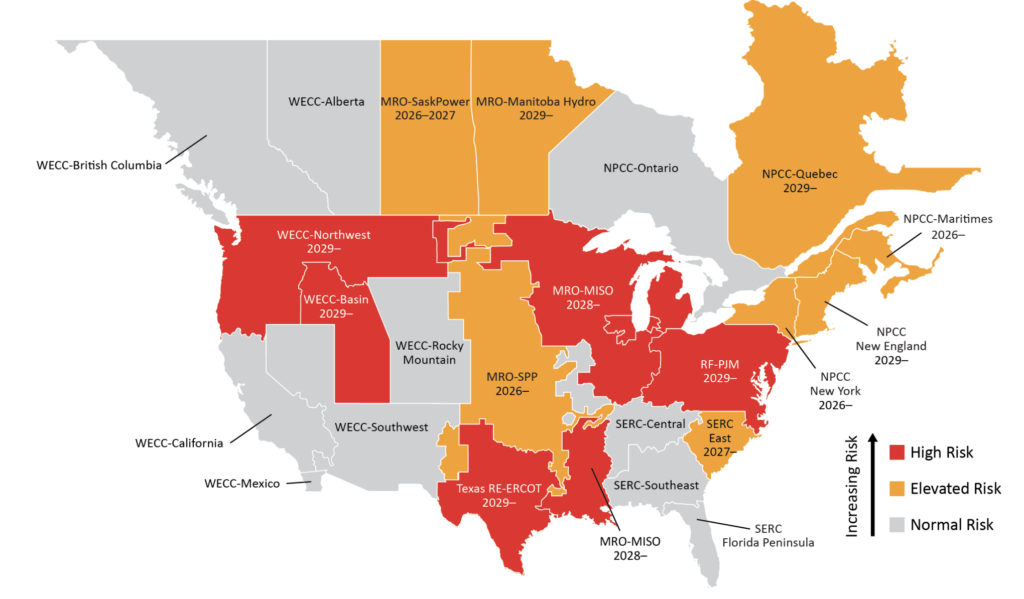

Texas and the Gulf Coast: Anchored by the prolific Permian Basin, Texas offers an unparalleled combination of abundant natural gas, extensive infrastructure, and a uniquely flexible electricity market. Under the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT), energy buyers enjoy direct procurement opportunities and the ability to develop on-site generation without traditional utility oversight.

The state’s deregulated, “energy-only” market structure rewards efficiency but can expose operators to scarcity pricing during peak demand. Nonetheless, Texas’s extensive pipeline networks, dual-fuel facilities, and thriving energy ecosystem—particularly around Midland, Odessa, and the Dallas-Fort Worth corridor—continue to attract hyperscale and colocation developers seeking both capacity and competitive rates.

Appalachian Basin (Pennsylvania, Ohio, West Virginia): Powered by the Marcellus and Utica shales, the Appalachian Basin has become one of the nation’s largest natural gas-producing regions. The area’s industrial heritage, abundant brownfield sites, and extensive pipeline corridors make it a natural fit for data center development.

That said, projects in this region often encounter a patchwork of state-level permitting regimes. Environmental approvals from agencies like Pennsylvania’s Department of Environmental Protection or Ohio’s Environmental Protection Agency are typically required for air emissions and on-site backup generation. Combined with fragmented grid structures and shifting regulatory positions on hydraulic fracturing, these factors demand careful legal and operational planning.

Midcontinent and Great Plains: Stretching from Oklahoma through Kansas and Arkansas, this region offers connectivity to the Permian and Anadarko basins and has emerged as an attractive alternative for developers seeking low land costs and streamlined siting procedures. Favorable zoning, proximity to processing hubs, and supportive local policies contribute to a conducive development environment. Still, operators must navigate state utility commission rules governing self-generation, interconnection, and easements, each carrying distinct compliance and risk considerations.

Rockies and Mountain West: Colorado’s DJ (Denver-Julesburg) Basin and Wyoming’s Powder River Basin are gaining traction as destinations for high-performance computing facilities and specialized data applications. State and local governments in the region have introduced tax incentives and expedited permitting programs designed to attract “energy-adjacent” infrastructure. However, heightened environmental scrutiny—particularly under NEPA and state environmental quality acts—requires detailed environmental due diligence, especially where development touches public lands or ecologically sensitive areas.

Gulf South and Southeastern Corridors: Louisiana and Mississippi, with their dense networks of pipelines and close proximity to liquefied natural gas (LNG) export terminals, offer developers reliable access to dispatchable power. The region’s mature energy infrastructure and alignment with gas-fired generation make it appealing for large-scale operations. Still, regulatory oversight by state public service commissions and interconnection processes managed by regional transmission organizations such as MISO can shape project timelines and economics.

Legal & Regulatory Frameworks

Siting data centers near natural gas assets activates a web of regulatory obligations spanning federal, state, and local jurisdictions. At the federal level, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) governs sales of power that cross state lines or involve independent producers. In vertically integrated states, public utility commissions may require approval for high-load interconnections or special tariff classifications.

Energy procurement structures often hinge on long-term contracts—such as power purchase agreements (PPAs) or gas tolling arrangements—that allocate pricing, supply, and environmental compliance risks between counterparties. The drafting of these agreements demands precision, as they must account for potential volatility in gas prices, interruption contingencies, and evolving regulatory mandates around emissions and carbon disclosure.

Environmental and land use compliance adds another layer of complexity. Projects near gas infrastructure frequently trigger Clean Air Act permitting, Section 401 water quality certifications, and state-level environmental reviews. Local zoning rules may also impose special-use permitting for industrial-scale facilities with on-site generation or high-voltage interconnection points. Meanwhile, growing investor pressure and proposed SEC climate disclosure rules are pushing operators toward greater transparency around carbon intensity and sustainability measures.

Evolving ESG & Carbon Policy

Even when powered primarily by natural gas, many data center developers are incorporating hybrid energy strategies to mitigate carbon exposure. Renewable Energy Credits, carbon offsets, and on-site solar or battery storage are now standard components of many facility portfolios. Others participate in voluntary carbon markets or state-level cap-and-trade regimes, integrating these tools into broader ESG commitments.

As the line between energy strategy and corporate sustainability continues to blur, legal teams must ensure that ESG representations made in financing or public disclosures accurately reflect operational realities. Misalignment between aspirational goals and tangible energy sourcing can trigger regulatory and reputational risks.

Contractual & Transactional Structuring

The co-location of data and energy assets is reshaping traditional deal structures. Site control agreements often include complex rights-of-way for pipelines, fiber networks, and transmission lines, each with unique indemnity and access provisions. Fuel supply contracts may distinguish between firm and interruptible transportation service, an allocation that directly affects both reliability and cost exposure.

Meanwhile, the growing integration of microgrids and combined heat and power (CHP) systems has introduced new partnership and joint venture models between developers, utilities, and private investors. These arrangements, while innovative, require robust allocation of operational risk, environmental liability, and insurance coverage for regulatory noncompliance or emissions-related claims. The intersection of infrastructure and energy law has never been more intricate or more essential to the data center economy.

While proximity to natural gas remains strategically advantageous, the legal environment is shifting under the weight of decarbonization policy. Several states—including Oregon, Virginia, and Illinois—are considering restrictions on fossil-fueled generation for new data centers. At the same time, federal incentives under the Inflation Reduction Act are accelerating investment in renewable energy and storage technologies, subtly realigning the economics of power procurement.

Still, the practical need for uninterrupted baseload power ensures that natural gas will remain a cornerstone of the data center landscape for years to come. Lawyers advising in this space must therefore balance traditional expertise in utility and environmental law with a growing command of carbon accounting, ESG reporting, and the policy frameworks that now influence infrastructure investment.

Conclusion

Locating data centers near natural gas resources represents far more than an energy strategy; it is a convergence of technology, regulation, and law. Texas’s deregulated grid, Appalachia’s shale fields, and the Gulf Coast’s energy corridors each offer opportunity tempered by regulatory complexity.

Success in this evolving environment demands more than engineering foresight; it requires legal fluency in energy markets, permitting, and compliance regimes that span multiple jurisdictions. As the digital economy expands, proximity to natural gas will continue to offer both competitive advantage and regulatory challenge—one that must be navigated with equal parts technical insight and legal precision.

—Warren Koshofer is a partner in the New York office of Michelman Robinson, an international law firm headquartered in Los Angeles, with additional locations in Irvine, San Francisco, Dallas, Houston, Chicago, and London. A member of M&R’s Commercial & Business Litigation Practice Group, Warren is well-versed in sustainability, energy, and related environmental issues impacting stakeholders across industries. He can be contacted at 212-730-7700 or wkoshofer@mrllp.com. Seth Liebenstein is also a partner Michelman Robinson’s New York office. A real estate lawyer who advises owners, developers, family offices, and investors in transactions involving multifamily assets, mixed-use properties, retail centers, and commercial buildings nationwide, Seth can be contacted at 212-730-7700 or sliebenstein@mrllp.com.