Officials in Germany are scaling back their plans to develop more natural gas–fired power plants, as the government wants to continue its path toward decarbonization while also recognizing the need to back up renewable power generation with baseload units. Chancellor Friedrich Merz and his Social Democrat coalition partners in November brokered a compromise between those who want the country to move faster in a transition away from thermal energy—the country is phasing out coal (Figure 1), and shut down its last nuclear reactor in 2023—and industry groups that are concerned about access to a dependable, affordable supply of power. The government in announcing its plan said it will be important for new gas-fired units to be able to burn hydrogen. Merz said any new tenders for power plants “will specify that the new power stations are technically capable of being fired by hydrogen.”

|

|

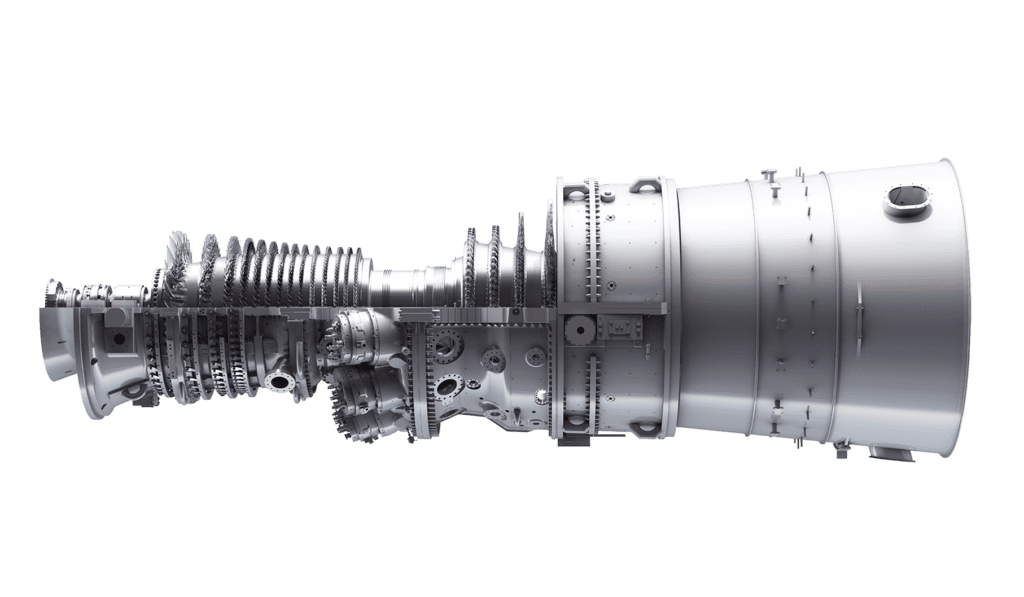

1. The Lünen coal-fired power plant is a 750-MW facility in North Rhine-Westphalia. The station, which received a Top Plant award from POWER in 2014, is Trianel’s main coal-fired power plant in Germany. The facility is facing closure as part of the country’s phase-out of coal-fired generation, and Trianel is looking at developing large-scale battery energy storage projects to replace plants like the Lünen facility. Trianel last summer said it would develop a 900-MW battery energy storage system in Waltrop in North Rhine-Westphalia. Courtesy: Siemens AG |

Merz recently said the European Commission (EC) had indicated it would support Germany’s energy plans. That includes commitments to build at least 2 GW of power generation capacity using any technology, which could include battery energy storage. Officials have said tenders for at least 8 GW of new generation will be issued this year, with an expectation of that generation entering commercial service by 2031. The government has said it wants the power sector to be carbon-neutral by 2045, which means some new units may need to install carbon capture and sequestration technology.

“The German government was forced to reduce its target by the European Commission, affecting the Merz plan for energy security. While these plants are hydrogen compatible, it is important to point out that there is no commercial hydrogen supply at this scale and there is no guarantee that the technology and infrastructure will be ready by 2030 or even 2045,” said Guido Núñez-Mujica, director of Data Science and senior policy advisor at Anthropocene Institute. “This gas is supposed to replace coal, however, even the 20 GW that were denied by the EC are insufficient to replace the approximately 30 GW of coal currently online.” Núñez-Mujica told POWER, “This is an unwelcome development for the German government, and might force them to look into resurrecting some nuclear power plants, keeping coal online for longer, or deepening the de-industrialization of Germany. Add to this the fact the clean energy volume this year is significantly lower than last year and highlighting how volatile this supply can be, and it is clear that Germany will have to face very tough choices in the future and likely a course correction will be forced sooner or later.”

Katherina Reiche, Germany’s economy and energy minister, already has said ensuring new gas-fired plants can run on hydrogen is problematic. Reiche told German media that it’s “unlikely” a sufficient amount of hydrogen would be available to run new units by 2030. Reiche in announcing a hydrogen plan in September of last year said she wants more flexibility when it comes to targets for hydrogen; the minister said the market should be based on a willingness to pay for the fuel. Reiche also said she wants to replace current expansion targets for electrolyzers, which produce hydrogen, with “flexible targets” based on demand-side projects. The minister said projects to produce hydrogen should be launched “as needed.”

Merz, who took office in May 2025, is part of a coalition of the conservative CDU/CSU alliance and the Social Democrats, or SPD. The groups’ campaign platform included pledges to speed a German economic recovery, which included lowering energy prices. Critics have said the government is not doing enough to support the economy, and is lacking in its effort to rebuild old, and construct new, infrastructure, including energy projects. A recent poll showed barely a quarter of the population has a favorable view of his administration after six months in office. The next scheduled election for chancellor is in 2029.

Germany has made strides with renewable energy; the International Energy Agency said more than half the country’s electricity was produced by wind, solar, hydropower, and biomass in the past couple of years, after the shutdown of nuclear power and curtailment of coal-fired units. The industrial sector, though, has cautioned that rising demand for power, particularly tied to a better economy, increases the need for more baseload generation to support intermittent renewable resources. That’s at odds with the country’s climate goals, and has brought calls for other measures—such as those being adopted in other countries—to increase the power supply.

Georg Rute, CEO of Gridraven, a provider of dynamic line rating technology for electricity transmission, told POWER: “Moving away from gas is a geopolitical necessity in Germany. In contrast, solar and wind promise energy security and stable prices. In order to support the strategy of 80% renewable power by 2030, Germany is aggressively strengthening its transmission grid. Much of the planned generation is wind power in the North Sea. TenneT, the grid operator that connects the North Sea to industry in the south [of Germany], recently announced a €65 billion ($75.5 billion) investment plan until 2029 to strengthen the grid. TenneT is also one of the few grid operators that has a long history with grid optimization tools such as dynamic line ratings, since additional capacity translates directly to more affordable power in Germany.”

German officials have supported the expansion and modernization of the power grid, which includes efforts to integrate more renewable energy resources, but there continues to be debate about how to align the demand for power with efforts to decarbonize. Irina Tsukerman, president of Scarab Rising and a political consultant, said the move to reduce the amount of new gas-fired generation “reflects the collision between three pressures: soaring demand for flexible capacity, the fiscal and political hangover from the energy crisis of 2022–2023, and a rapidly hardening European climate and industrial policy environment. The original 20-GW target, floated in the first half of 2025, looked like a classic German compromise: gas as a ‘bridge’ to balance intermittent renewables once coal exits and nuclear is already gone. It was never only about engineering. It was also about buying time for a grid and a political system that had been forced into emergency improvisation after Russian pipeline flows collapsed and prices spiked to historic levels. The November retreat to 10 GW is an acknowledgment that the bridge was becoming too long and too expensive, and that Berlin cannot afford to signal that it intends to anchor its entire balancing strategy in imported gas for another generation.”

Tsukerman, a frequent contributor to POWER, said Germany is facing headwinds when it comes to energy. “The first hard constraint is money. After the 2022–2023 crisis, Berlin poured literally tens of billions of euros into shielding households and industry from gas and power prices, building floating LNG [liquefied natural gas] terminals at record speed, and recapitalizing utilities that had been caught short by the collapse of Russian supply. Those measures were layered on top of an already ambitious climate and industrial support agenda, including large subsidies for green hydrogen, battery factories, and heat pump deployment.”

Tsukerman added: “At the current juncture, the finance ministry officials are staring at structural deficits, courts have pushed back on off-budget climate funds, and every long-term infrastructure signal is being scrutinized, including by the public. Twenty gigawatts of new gas capacity implies tens of billions in capital expenditure, long-term contracts, and capacity payments. Halving the target is an attempt to square the circle: promise enough new dispatchable capacity to calm utilities and heavy industry, while trimming the fiscal and political exposure of locking in that much gas.”

Critics of the plan to build more gas-fired plants, even when they could be converted to burn hydrogen, warn that not having a strategy to produce the needed hydrogen will subvert Germany’s climate goals. Industry analysts have said government subsidies—which are considered unlikely in the current economic climate—would be needed to make hydrogen production viable. Reiche told German media, “We are actively working on ramping up hydrogen production,” while admitting enough hydrogen will not be available by 2030. “We are therefore relying on gas-fired power plants for our security of supply, otherwise coal-fired power plants would have to run longer,” Reiche said.

Germany’s previous government had said it wanted any new gas-fired power plants to be hydrogen-capable, using green hydrogen produced from renewable energy resources. Reiche’s predecessor, Robert Habeck of the Green Party, had said his office would issue requirements for gas-fired plants to switch to hydrogen, but the prior government dissolved before any regulations were issued.

Tsukerman said revisions to Germany’s energy plan put the country in a delicate position. “The country is committing to higher electricity demand as it electrifies heating, transport, and parts of industry, while simultaneously shrinking the pool of firm, dispatchable capacity that can be turned on at will in bad weather years. The choice to halve the gas target is a wager on the speed and scale of the renewables and flexibility buildout. If wind and solar deployment stalls again, if storage remains a niche, or if interconnector upgrades lag behind, Berlin will face hard choices such as whether to extend coal longer than planned, to squeeze industry with higher prices and enforced curtailments, or to revisit the gas cap it has just put in place,” she said.

“There is also a geopolitical dimension,” said Tsukerman, addressing the impact of Germany’s generation portfolio on other countries. “Germany’s reduced appetite for gas capacity changes the long-term expectations of LNG exporters from the U.S., Qatar, and others who had hoped to lock in German buyers for decades. Shorter contracts, smaller volume commitments, and a clearer signal that gas demand is expected to peak and decline make Germany a less attractive anchor customer for new upstream projects. That, in turn, reinforces the global narrative that Europe is transitioning away from fossil fuels more rapidly than many producers hoped, and that gas will face the same structural demand erosion that coal is already experiencing.”

—Darrell Proctor is a senior editor for POWER.