The rapid rise of data centers has put many power industry demand forecasters on edge. Some predict the power-hungry nature of the facilities will quickly create problems for utilities and the grid. ICIS, a data analytics provider, calculates that in 2024, demand from data centers in Europe accounted for 96 TWh, or 3.1% of total power demand.

“Now, you could say it’s not a lot—3%—it’s just a marginal size, but I’m going to spice it up a bit with two additional layers,” Matteo Mazzoni, director of Energy Analytics at ICIS, said as a guest on The POWER Podcast. “One is: that power demand is very consolidated in just a small subset of countries. So, five countries account of over 60% of that European power demand. And within those five countries, which are the usual suspects in terms of Germany, France, the UK, Ireland, and Netherlands, half of that consumption is located in the FLAP-D market, which sounds like a fancy new coffee, but in reality is just five big cities: Frankfurt, London, Amsterdam, Paris, and Dublin.”

Predicting where and how data center demand will grow in the future is challenging, however, especially when looking out more than a few years. “What we’ve tried to do with our research is to divide it into two main time frames,” Mazzoni explained. “The next three to five years, where we see our forecast being relatively accurate because we looked at the development of new data centers, where they are being built, and all the information that are currently available. And, then, what might happen past 2030, which is a little bit more uncertain given how fast technology is developing and all that is happening on the AI [artificial intelligence] front.”

Based on its research, ICIS expects European data center power demand to grow 75% by 2030, to 168 TWh. “It’s going to be a lot of the same,” Mazzoni predicted. “So, those big centers—those big cities—are still set to attract most of the additional data center consumption, but we see the emergence of also new interesting markets, like the Nordics and to a certain extent also southern Europe with Iberia [especially Spain] being an interesting market.”

Meanwhile, the types of data centers being added to the grid also matter. Computation-focused data centers, which handle tasks related to AI, machine learning, and other scientific simulations, consume much more energy than storage-focused data centers, which simply archive information. Furthermore, there are notable operational differences between data centers used for AI training, the process of teaching an AI model by exposing it to large datasets, and inference, that is, using a trained model to make predictions or generate outputs. While training can be done in remote data centers where resources are abundant, inference is very latency-sensitive and requires proximity to metropolitan hubs to ensure quick response times for user interfaces and applications.

The ICIS report tries to put everything into context. It says, “GPT-3, the LLM [large language model] developed by OpenAI that kickstarted ChatGPT, has 175 billion trainable parameters and consists of 96 layers. By using OpenAI’s documentation, we can estimate that GPT-3 required roughly 1,250 MWh for the training. The training of the GPT-4, with 100 trillion parameters, required 7,200 MWh, five times the electricity consumed for the previous version.

“If we look at the inference side, instead, we have an estimated consumption of 3–5 Wh per query, which multiplied by 10 million daily queries results in a daily consumption of 3,000–5,000 kWh, or 1,100–1,800 MWh per year, equal to the annual consumption of roughly 2,600 European families,” the report says.

“AI is a game changer,” said Mazzoni. “The impact of generative AI is not just that it is going to increase the number of data centers, which is expected to double in Europe and more than double in the U.S. and China, what we’ll do is we’ll substantially increase the amount of power required to run many more data centers.”

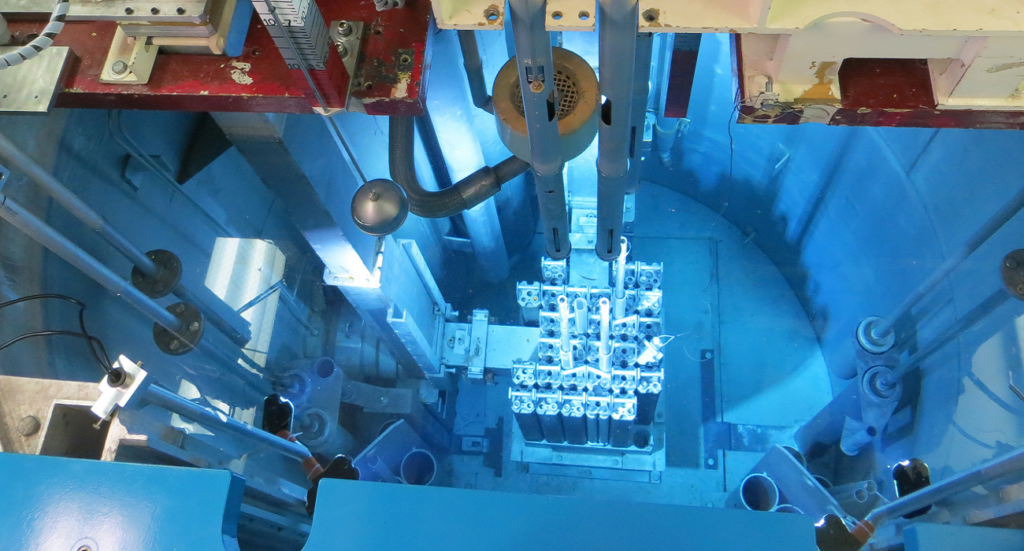

Yet, there is still a fair amount of uncertainty around demand projections. Advances in liquid cooling methods will likely reduce data center power usage. That’s because liquid cooling offers more efficient heat dissipation, which translates directly into lower electricity consumption.

Additionally, there are opportunities for further improvement in power usage effectiveness (PUE), which is a widely used data center energy efficiency metric. At the global level, the average PUE has decreased from 2.5 in 2007 to a current average of 1.56, according to the ICIS report. However, new facilities consistently achieve a PUE of 1.3 and sometimes much better. Google, which has many state-of-the-art and highly efficient data centers, reported a global average PUE of 1.09 for its facilities over the last year.

Said Mazzoni, “An expert in the field told us when we were doing our research, when tech moves out of the equation and you have energy engineers stepping in, you start to see that a lot of efficiency improvements will come, and demand will inevitably fall.”

Thus, data center load growth projections should be taken with a grain of salt. “The forecast that we have beyond 2030 will need to be revised,” Mazzoni predicted. “If we look at the history of the past 20 years—all analysts and all forecasts around load growth—they all overshoot what eventually happened. The first time it happened when the internet arrived—there was obviously great expectations—and then EVs, electric vehicles, and then heat pumps. But if we look at, for example, last year—2024—European power demand was up by 1.3%, U.S. power demand was up by 1.8%, and probably weather was the main driver behind that growth.”

To hear the full interview with Mazzoni, which contains much more about geographic trends, data center architecture redesigns, policy considerations, how data centers could affect renewable energy targets, and more, listen to The POWER Podcast. Click on the SoundCloud player below to listen in your browser now or use the following links to reach the show page on your favorite podcast platform:

For more power podcasts, visit The POWER Podcast archives.

—Aaron Larson is POWER’s executive editor (@AaronL_Power, @POWERmagazine).