The Tennessee Valley Authority’s third coal plant conversion to gas combined cycle generation, at the venerable Allen plant near Memphis, Tennessee, created the most-efficient combined cycle plant in its fleet of natural gas units, and a continuation of the once coal-dominated utility’s conversion to low-emissions technologies, starting with gas.

In April, the Tennessee Valley Authority’s (TVA’s) new, 1,100-MW, three-unit Allen combined cycle gas-fired power plant went into commercial operation five miles southwest of downtown Memphis. It is an iconic plant, as it replaces two elderly, 900-MW nameplate capacity (and 741-MW average generation) coal-fired units, which began commercial operation in 1959. A third unit, still operating, went commercial in 1970.

That’s a story reflecting a decade-long trend in generation at the regional public power giant TVA, where for decades coal was king. At its peak, TVA was the largest coal generating utility in the nation. Since 2007, TVA has built seven gas-fired combined cycle generating plants, with the Allen plant going into commercial operation last April, along with scores of combustion turbines at nine stations.

The Allen project is the third time TVA has directly replaced coal-fired generation with combined cycle gas power. In 2012, TVA built the 880-MW John Sevier combined cycle project, near Rogersville, Tennessee, to supplant four coal-fired generating units. In 2017, the federal power agency replaced two of its legendary Paradise coal-fired units in western Kentucky with a 1,000-MW combined cycle generating system, which earned a POWER Top Plant award in 2017. Omaha-based Kiewit Corp. was the engineer at Sevier, and engineer and constructor at the Paradise and Allen projects.

Dan Langstraat, Kiewit’s project manager for the engineering portion of the Allen and Paradise contracts, told POWER, “TVA is a federal government agency and had to bid the work competitively. We had to win the job.” However, he acknowledged that having a good working history with TVA could have been a benefit.

In late August, TVA announced it is considering closing the 1,150-MW Unit 3 at Paradise, which went into service in 1970. TVA said it will also consider shutting down its 950-MW, circa 1967 Bull Run coal-fired plant in eastern Kentucky.

The announcement by the TVA board came a day after the Trump administration’s Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced its Affordable Clean Energy rule, designed to replace the Obama administration’s Clean Power Plan, which never was implemented. The current administration is taking steps that it hopes will revive the dying U.S. steam coal industry, without much evidence of success.

The Allen site includes a megawatt of solar capacity designed to supply power for the site. The project also involves a deal with the city of Memphis, which was the original owner of the Allen plant, to use methane captured from a wastewater treatment plant located near the combined cycle plant. TVA invested $20 million for equipment to clean, dry, and transport the methane to the generating plant.

Learning Curve

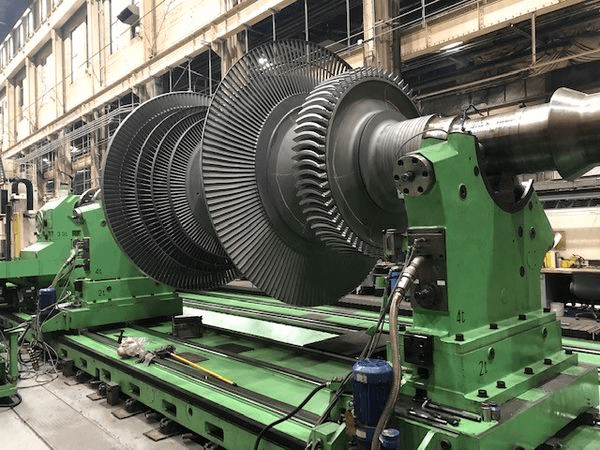

The Allen plant consists of two GE 7HA.02 combustion turbines (Figure 1) and a Toshiba steam turbine. The GE turbines were the fifth and sixth off of the company’s assembly line in Greenville, South Carolina, after the first four were bought by Exelon. The design offers a new combined cycle efficiency of 62% to 65%, according to GE. Construction began in 2015 and came in under budget and ahead of schedule.

The Allen project was designed as a companion to the Paradise work, following it by about a year. Dan Tibbs, TVA general manager for major projects, said, “The Allen project was intentionally co-developed with the similarly-sized Paradise project, such that equipment could be replicated and contracts leveraged.” He said that arrangement allowed TVA and Kiewit “to foresee potential issues a year ahead of time. This allowed us to immediately mitigate risks and very effectively implement a significant number of lessons learned.”

Problem Solving

While the Paradise project gave TVA and Kiewit a head start at the Allen combined cycle plant, the team did have to make some unique adjustments at Allen. Those largely involved the differences between the F-class GE combustion turbines used at Paradise and the newer, more-efficient H-class turbines installed at Allen (and a first for Kiewit). The issue involved the geometry of the generator terminals and the isolated phase bus terminals, which carry the very large currents from the generator to the step-up transformer. They are configured differently on the F-class and H-class generators.

This difference complicated the structural engineering of the plant. Kiewit knew this going into the job, Langstraat said. GE held a meeting with Kiewit and the others involved in the job before it began and provided copious details about the new combustion turbines. “It was not a surprise,” he said.

Dan Ross, GE vice president of North American sales, told POWER, “These projects are incredibly complex. From day one, we involved Kiewit on issues of constructability. Constructability and long-term maintenance are super important to the customer. From the start, the teams knocked down all barriers and worked with an intense focus on the sharing of ideas and information.”

According to Kiewit, the engineering and construction team then met with GE’s structural steel supplier J&G Steel. Kiewit said it and J&G were able to come up with some design tweaks. “The final design was very clean and efficient,” said Kiewit, “with almost no Kiewit-furnished steel columns landing on the foundation, which provides TVA with easy access to the equipment in that area.”

Further differences between the F-class and H-class machines also produced a problem. “The generator of an H-class machine is more similar to a steam turbine-style generator than a typical combustion turbine generator,” said Kiewit. That led to a need for GE to rearrange the generator lube oil and compressed gas piping supply, “which was completed seamlessly.”

Integrating the solar field into the balance of plant’s 6.9-kV switchgear was also a challenge. The trick was successfully converting the solar field’s direct current (DC) voltage to alternating current (AC). The solution was a program that allows more sensitivity in the DC-to-AC inverter, “with the ability to signal the upstream breaker if there is a problem electronically.”

The Roots of the Project

The Sevier, Paradise, and Allen coal-to-gas conversion projects were the result of a 2011 consent agreement with the EPA to close the plants in Tennessee, Alabama, and Kentucky to reduce conventional pollutants, including sulfur dioxide, oxides of nitrogen, and fine particulates. The settlement involved the three states and four environmental advocacy groups, as well as TVA and the EPA. The deadline for compliance was December 2018.

The deal required TVA to either install advanced pollution control equipment or retire Sevier, Allen, and the first two Paradise units. In 2014, TVA announced it would spend $975 million to convert Allen to natural gas. The Paradise conversion was announced in 2013.

The Allen coal plant originated with Memphis Light, Gas, and Water, which began construction in 1956. Commercial generation began in 1959, serving the city’s baseload needs. It was named after Thomas H. Allen, the former president of the municipal utility. In 1964, TVA began operating the plant for the muni. TVA bought the Allen plant outright in 1984.

While the Allen conversion, and the earlier Paradise and Sevier jobs, were driven by environmental regulations, that’s not generally been the case in TVA’s retreat from coal. The engine of change has been pure economics, and the long-term declines in the cost of natural gas and renewable generation. “The moves we have made in the generation fleet have been driven by economics more than environmental regulation,” TVA CEO Bill Johnson told his board in August.

In addition, TVA’s electric demand has not grown, even though the region’s population has increased. That’s a result of more-efficient electric appliances and customer conservation. Johnson has said that situation is “real” and, most likely, “permanent.” At TVA’s quarterly board of directors meeting in Knoxville in August, Johnson said that TVA’s remaining baseload coal fleet was not well-suited to follow load rapidly, a characteristic that gas offers.

In 2007, TVA’s generating mix consisted of 58% coal, 26% nuclear, 10% gas, and 6% hydro. This year, the mix is 40% nuclear; 26% coal; 20% gas; 10% hydro; and 4% wind, solar, and energy efficiency. Today, TVA has six coal-fired stations operating 26 generating units: the Bull Run unit; the 2,600-MW, two-unit Cumberland station in Tennessee; the 988-MW, four-unit Gallatin station in Tennessee; the 1,700-MW, nine-unit Kingston station in Tennessee; the 1,750-MW, nine-unit Shawnee station in Kentucky; and Paradise Unit 3. Closure of the final unit at Paradise and the Bull Run station would reduce TVA’s coal portfolio to four stations and cut its coal-fired generating capacity by some 2,100 MW, or more than 20%.

In addition to regulatory and economic pressures, TVA’s shift from coal to gas and renewables is a product of the giant federal power agency’s integrated resource plan (IRP). In 2015, TVA adopted a major IRP, a first for the system, which charted its course for the next five years. “I’ve been reading IRPs since the mid-1990s,” Johnson, a veteran utility executive, said at the time. “This is a unique IRP because it treats efficiency and renewables as resources,” not as afterthoughts.

The 2015 IRP states, “We paved new ground by developing a unique way to measure and model the financial costs of energy efficiency and renewable resources as if they were traditional power plants. This method is a more disciplined approach than ever before that we believe creates a much better picture of how all resources can be best utilized to support load growth in the Valley.”

Today, TVA is working on an update to the 2015 plan. It said, “The 2019 IRP will explore various scenarios related to expansion of distributed energy resources (DER) in the Tennessee Valley. We will also seek to improve TVA’s understanding of the impact and benefit of system flexibility with increasing renewable and distributed resources.”

The American Public Power Association commented that the big picture for TVA is “that demand in TVA’s territory has been essentially flat over the past five years, and that trend is expected to continue as technological advances, consumer demand for generation and energy management technologies, and distributed energy increase.”

That suggests even more pressure on the existing coal-fired units, and the continuing possibilities for conversions to gas combined cycle projects similar to the Allen conversion. Should TVA decide on more combined cycle projects, expect Kiewit to be among the bidders. Over the last several years, “combined cycle has been our bread and butter,” said Langstraat. ■

—Kennedy Maize is a long-time energy journalist and frequent contributor to POWER.