The Trump administration is touting a proposed 9.2‑GW natural gas power complex near Portsmouth, Ohio, as the centerpiece of a new U.S.–Japan trade deal that officials say could steer up to $550 billion of Japanese capital into American energy and industrial projects.

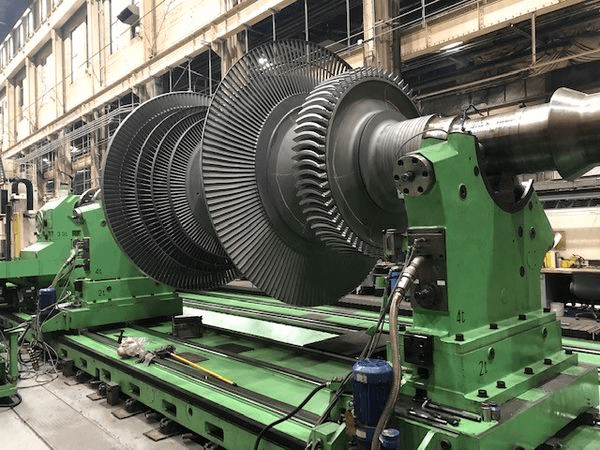

According to a Feb. 17 Commerce Department fact sheet and a statement by Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick, the “Portsmouth Powered Land Project” would be a 9.2‑GW, $33 billion natural gas plant in the vicinity of Portsmouth, operated by Japanese conglomerate SoftBank’s U.S. affiliate, SB Energy.

Billed as one of the “largest natural gas generation projects in the world,” the facility “represents a strategic initiative to create an integrated platform capable of supplying reliable, large‑scale, dispatchable energy,” the Commerce Department said.

But beyond those claims, neither the government nor the developer has released other basic details such as plant configuration, permitting path, interconnection plan, financing structure, or target in‑service date. Some politicians have suggested more details may be forthcoming in President Trump’s State of the Union speech on Feb. 24.

The Ohio mega‑project is one of three deals in a first $36 billion tranche the Trump administration credits to a U.S.–Japan “strategic investment” framework first announced in July 2025 and formally implemented by executive order that September, under which the White House said Tokyo has pledged up to $550 billion for U.S. projects in return for a 15% tariff cap on most Japanese imports. In that EO, the White House noted the “investments” will be selected by the U.S. government.

The second project that will benefit under the $36 billion “commitment” is a $2.1 billion deepwater crude export terminal off Brazoria County, Texas. That project, tied to the Texas GulfLink project, is expected to generate “$20–30 billion in U.S. crude exports annually” and “expand American energy dominance,” Commerce said. The third project is an approximately $600 million high‑pressure synthetic diamond grit facility in Georgia operated by Element Six, which Commerce calls “critical” to U.S. industrial manufacturing and national security because diamond grit is “vital” to the semiconductor, automotive, and oil and gas industries.

A Mega Power Plant—on Paper

SB Energy is a fully integrated U.S. digital‑infrastructure and energy platform founded in 2019 and owned by SoftBank, which describes it as a group company and AI‑infrastructure developer. SoftBank, a Japan‑based technology and investment conglomerate best known for its multitrillion‑yen Vision Funds and major stakes in AI and semiconductor companies, now treats SB Energy as one of its core “AI infrastructure” holdings.

SB Energy says it has raised more than $10 billion in project capital and built a 5‑GW‑plus portfolio of utility‑scale solar, storage, and powered‑land projects that are operating or under construction in Texas and California, including the 900‑MW Orion Solar Belt complex serving Google’s Midlothian data center in Milam County, Texas; the 402‑MW Athos battery storage project in Riverside County, California; and the Pelican’s Jaw solar‑plus‑storage project in Kern County, California.

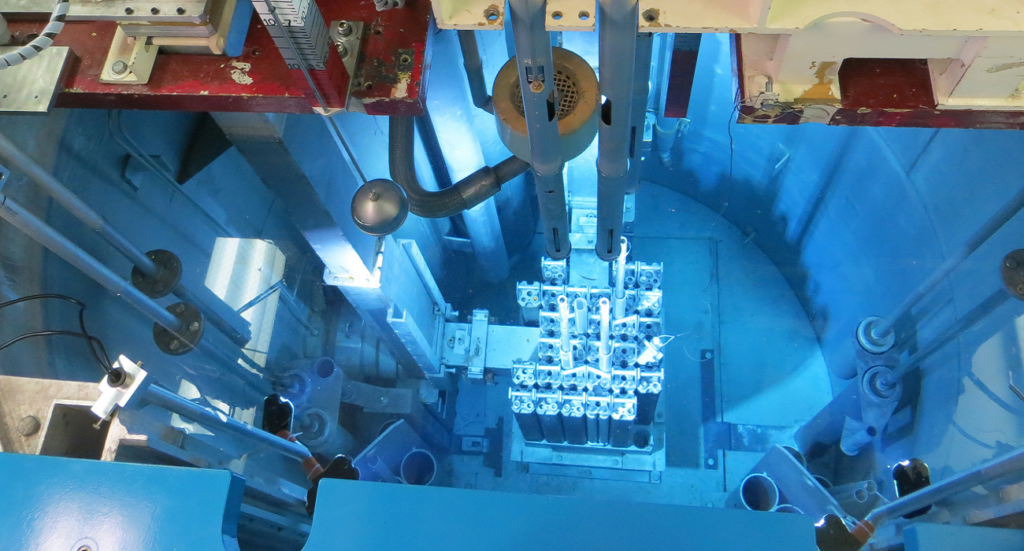

In January 2026, notably, SoftBank and AI research and deployment company OpenAI each invested $500 million of equity into SB Energy and signed a 1.2‑GW data‑center lease in Milam County, Texas, as part of OpenAI’s Stargate initiative, a White House–backed plan to build “next‑generation AI data centers” in the U.S. The deal makes SB Energy OpenAI’s preferred development and execution partner for multi‑gigawatt AI data‑center campuses and their associated generation. It also brings SB Energy into a non‑exclusive “preferred partnership” with SoftBank and OpenAI to roll out a repeatable data‑center design model and builds on an earlier $800 million redeemable‑preferred investment from Ares and SB Energy’s acquisition of Studio 151, a data‑center engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) and operations firm, which has experience on roughly 20 campuses.

While Portsmouth is located in Scioto County, as of February 19, 2026, the Pike County Economic Development Director and Scioto County Commissioners have both reportedly said they have no information on where the touted Ohio site for the Portsmouth Powered Land Project, the deal’s mega gas power project, would actually be sited.

Portsmouth sits in the vicinity of several Department of Energy (DOE) sites. Just up the Scioto River from Portsmouth is the DOE’s 3,700‑acre Portsmouth site in Piketon, a Cold War–era uranium enrichment complex now in long‑term decommissioning. The DOE and its community reuse organization, the Southern Ohio Diversification Initiative (SODI), have spent more than a decade carving the complex into transferable parcels and marketing it as a “PORTS Mega Site” for energy‑intensive industry, backed by up to 4,860 MW of delivery capacity from 765‑, 345‑, and 138‑kV lines and an existing 345‑kV substation tied into both PJM and MISO.

In January, as POWER reported in depth, hyperscaler Meta unveiled an agreement with advanced nuclear firm Oklo that will underpin the development of a 1.2-GW Aurora powerhouse campus in Pike County, Ohio, to support Meta’s regional data centers, including its Prometheus AI supercluster, which Meta is building in the Columbus area in New Albany, about 100 miles away.

The Piketon site, notably, also hosts Centrus Energy’s American Centrifuge Plant, where the company is producing high-assay low-enriched uranium and is preparing for an expansion.

Project Likely to Feed Growing Load in Ohio

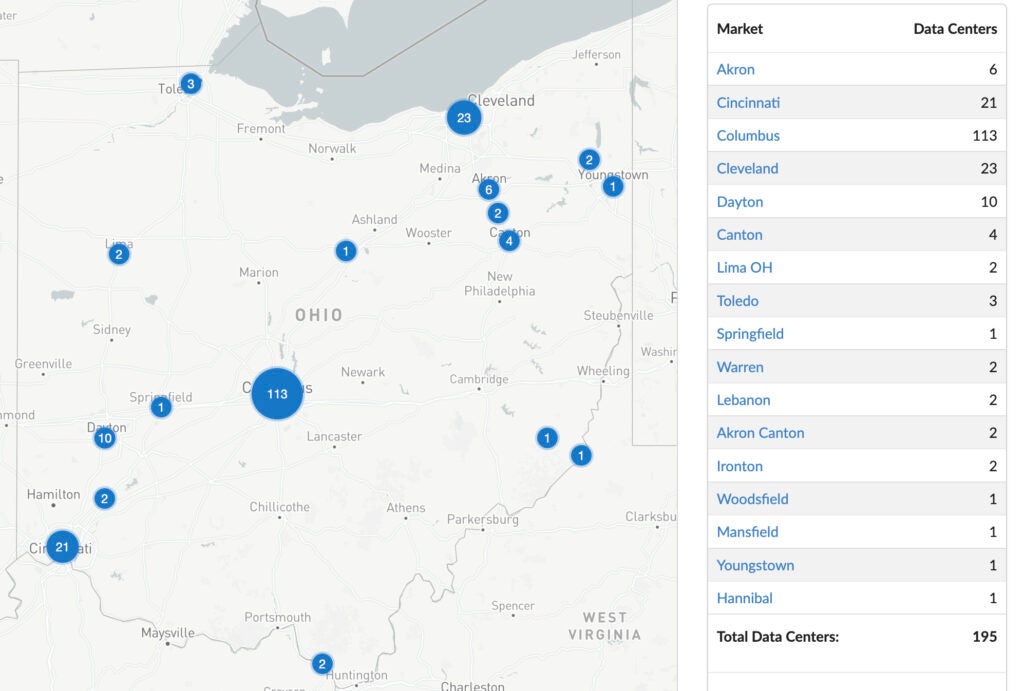

The new 9.2-GW power project will likely feed intense power demand growing in central Ohio, where land availability, transmission access, and proximity to consumers make development attractive for data centers. According to the Office of the Ohio Consumers’ Counsel, Ohio has about 200 data centers, making it the fifth-highest state in the country, though most are in Central Ohio.

AEP Ohio, a utility that serves the region, has suggested that data center load in central Ohio grew from 100 MW in 2020 to around 600 MW in 2024. AEP Ohio forecasts that load could rapidly accelerate to reach 5 GW in Central Ohio by 2030. In July 2025, Ohio regulators approved the utility’s landmark tariff structure requiring large new data center customers to pay for a minimum of 85% of their subscribed electricity usage—regardless of actual consumption—for up to 12 years.

If built, the 9.2-GW Portsmouth gas power complex would likely connect to PJM Interconnection, the nation’s largest regional grid operator, which oversees transmission and wholesale markets across parts of 13 states and the District of Columbia.

However, PJM was not aware of the project before the Trump administration announced it, PJM spokesperson Dan Lockwood told POWER. “But we are excited about its prospects due to the need for new supply to meet burgeoning data center/large load demand growth,” he said. In January, the grid operator suggested that while it adjusted its load growth estimates, it projects unusually steep growth. Summer peak demand is slated to rise about 3.6% a year over the next decade and 2.4% annually over 20 years, driven largely by roughly 30 GW of new data‑center load by 2030 and broader electrification, it has said.

If the project does pan out and needs grid connection, however, it “would be treated like any other interconnection project, and would be welcome to apply with the opening of Cycle 1 in April,” Lockwood noted. Implementing recent reforms, PJM is transitioning from its former first-come, first-served queue to a “clustered” cycle process designed to clear a massive backlog and prioritize projects most likely to get built. In September 2025, PJM announced it had completed Transition Cycle 1 studies, issuing draft agreements for 130 projects totaling about 17.4 GW. Transition Cycle 2 remains in the backlog-clearing phase, with completion targeted by the end of 2026. The first regular window under the fully reformed framework opens in April, with applications due April 27, 2026.

Still, projects accepted into that cluster can expect roughly a one- to two-year study process before receiving a final Generation Interconnection Agreement, PJM noted. That could mean the 9.2‑GW project would need to enter a structured, competitive review and face detailed transmission studies, upgrade cost allocations, and binding terms that determine whether—and at what cost—it can connect to PJM’s grid.

PJM politics, however, continue to evolve. In January, notably, the governors of all 13 states within PJM’s footprint joined Trump’s Energy Dominance Council in a non‑binding “Statement of Principles” that urges PJM to run a one‑off reliability backstop auction offering 15‑year capacity contracts for new plants, create large‑load rate classes so data centers shoulder more of those costs, tighten load forecasts, and cap interconnection studies at 150 days.

PJM’s board has since ordered staff to begin designing the backstop auction and opened stakeholder talks on whether an emergency procurement could be held as early as September, but any changes will still require tariff filings and FERC approval before they can reshape project development. If adopted largely as envisioned, the backstop auction would give projects like Portsmouth a new path to secure long‑term capacity contracts while shifting more of the cost of that new capacity toward large data‑center customers rather than ordinary ratepayers.

At the same time, analysts note that the governors’ Statement of Principles and the proposed backstop auction cover only a subset of PJM’s capacity barriers, given that they would focus mainly on market design, load tariffs, and forecasting, while leaving big structural constraints such as permitting, transmission build‑out, equipment lead times, and broader load‑flexibility issues largely unresolved. They also warn that even if framed as a one‑off, a reliability backstop auction could evolve into a more permanent parallel capacity mechanism if shortfalls persist, which could mean potentially long‑term implications for how projects like Portsmouth compete in PJM’s market.

A Trade Deal With Big—Albeit Murky—Implications for Power Projects

Finally, while details may be yet forthcoming, the trade deal remains unusual. In July 2025, Trump and Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi announced a “strategic trade and investment agreement” under which the U.S. would levy a flat 15% tariff on most Japanese imports instead of the 25% rate Trump had threatened, and Japan would pledge up to $550 billion of investment in U.S. “strategic” sectors. “This amount is equivalent to about 12% of Japan’s 2024 GDP,” analysts at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis noted in November 2025, adding that Tokyo has signaled it will provide “up to $550 billion in financial support” mainly through public financial institutions such as the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC), in the form of subsidized loans, loan guarantees, and other credit mechanisms rather than straight equity.

In September 2025, Trump issued Executive Order 14345 to implement key tariff provisions of the framework, while Washington and Tokyo signed a separate memorandum of understanding (MOU) that lays out how Japan’s $550 billion pledge is to be deployed. The MOU suggests a U.S. Investment Committee (established by Trump and chaired by the commerce secretary) will identify and recommend projects in “strategic” sectors such as semiconductors, critical minerals, shipbuilding, energy and AI. But the president, alone, would decide which “investments” Japan will be asked to fund. For each approved project, the U.S. is to establish a special‑purpose vehicle it controls, and Japan then has at least 45 business days to decide whether to provide the requested “investment amount,” typically via JBIC- or NEXI‑backed loans whose interest spread is capped at levels similar to other long‑dated infrastructure debt.

The MOU specified that cash flows from each investment are paid 50/50 to Washington and Tokyo until Japan has recouped a contractually defined “deemed allocation amount” (principal plus agreed interest), after which the split shifts to 90% for the U.S. and 10% for Japan. If, after consultations, Japan declines to fund a selected project, the U.S. can both tilt the profit‑sharing further in its own favor and raise tariffs on Japanese imports above the framework’s 15% baseline. The $36 billion “first tranche” of three projects—including the proposed Portsmouth gas complex—announced in February 2026 mark the first concrete application of that framework and MOU.

U.S.-Japan Trade Deal: Potential Energy Projects and Investments

However, both sides have since outlined several potential investments and projects that may be considered.

Energy

Westinghouse—Construction of AP1000 nuclear reactors and small modular reactors (SMRs), with possible involvement of Japanese suppliers and operators, including Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Toshiba Group, and IHI (up to $100 billion). (In an October 2025 announcement, Westinghouse, Cameco, and Brookfield Asset Management said they entered into a “strategic partnership to accelerate the deployment of nuclear power” and build “at least $80 billion of new reactors across the U.S.” using Westinghouse technology. While no details have been formally disclosed, Westinghouse has told POWER it is fielding a substantial pipeline.)

GE Vernova–Hitachi—Construction of BWRX‑300 SMRs with participation from Hitachi GE Vernova Nuclear Energy (Hitachi holds 80.01% of the shares in Hitachi GE Vernova Nuclear Energy while GE Vernova holds 19.99%) and other Japanese companies (up to $100 billion). Hitachi in October 2025 said it is committed to supporting SMR construction “through the provision of equipment and engineering services.” The BWRX-300 was developed collaboratively by GE Vernova Hitachi Nuclear Energy and Hitachi-GE Nuclear Energy, and Hitachi-GE Nuclear Energy has been actively involved in the design process of the reactor.

Bechtel—Project management, EPC for large power and industrial infrastructure, including power plants, substations, and transmission systems serving mission‑critical facilities, with Japanese partners under consideration (up to $25 billion).

Kiewit—EPC services for large‑scale power and industrial infrastructure, with possible Japanese participation (up to $25 billion).

GE Vernova—Supply of large gas and steam turbines, generators, and high‑voltage direct current and substation equipment for grid‑electrification and stabilization projects tied to mission‑critical loads, with Japanese firms expected to be involved (up to $25 billion).

SoftBank Group—Specification, design, procurement, assembly, integration, operations, and maintenance for large‑scale power infrastructure (up to $25 billion). SoftBank, through its U.S. affiliate SB Energy, is a lead developer of the 9.2‑GW gas‑fired projectas reported above, is a lead developer of the 9.2-GW gas-fired project in the U.S.-Japan deal that Commerce said will cost $33 billion.

Carrier—Thermal‑cooling systems and solutions, including chillers, air‑handling units, and coolant distribution units for power infrastructure, with Japanese partners contemplated (up to $20 billion).

Kinder Morgan—Natural gas transmission and other power‑infrastructure services, with potential involvement of Japanese companies (up to $7 billion).

Power and AI infrastructure

NuScale / ENTRA1 Energy—Development of large‑scale baseload power plants, including gas‑fired and nuclear projects using NuScale SMR technology, in an AI‑focused initiative aimed at serving data‑center, manufacturing, and national‑defense loads. ENTRA1 in October 2025 said it was positioned to receive up to $25 billion in investment capital.

Toshiba—Supply of electrical power modules, data‑center transformers, and other substation equipment to bolster U.S. power‑equipment supply chains (up to $25 billion).

Hitachi—Along with the BWRX-300 SMR project, Hitachi will be potentially tapped to structure projects for power infrastructure, including HVDC transmission links, substations, and transformers for data centers, to strengthen supply chains.

Mitsubishi Electric—Power‑station systems such as generators and transmission and distribution equipment, plus data‑center gear including UPS units, IT‑cooling chillers, substation systems, and emergency diesel generators (up to $30 billion). In October, Mitsubishi Electric said it would invest $86 billion in advanced switchgear and power-electronics production in the U.S.

TDK—Advanced electronic components and power modules for AI and digital infrastructure, including components for power‑conversion and control systems (up to $25 billion).

Fujikura—Optical fiber cables and related products to support data‑center networks and other AI‑related communications infrastructure (up to $20 billion).

Murata Manufacturing—Electronic components such as multilayer ceramic capacitors, inductors, and EMI filters, along with battery modules and other hardware for backup power and energy‑storage systems, including AC‑DC and DC‑DC converter modules and lithium‑ion products (up to $15 billion).

Panasonic—Energy‑storage systems and other electronics to support U.S. supply chains (up to $15 billion). Panasonic CEO Yuki Kusumi, in January 2026, revealed that Panasonic has agreed to invest up to $15 billion “to supply energy storage systems, other electronic devices and components, and strengthen supply chains in the U.S.”

—Sonal Patel is a POWER senior editor (@sonalcpatel, @POWERmagazine).