In July, the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) announced that for the first time since its record-keeping began, natural gas in April reached parity with coal in electricity generation. With gas prices at inflation-adjusted record lows, utilities have been running gas-fired plants at unprecedented levels. Despite the low prices, dry gas production in the Marcellus shale region continues to grow strongly.

In light of these developments, you might reasonably assume that gas pipeline construction has kept pace with the demand for capacity. But such an assumption would be very wrong.

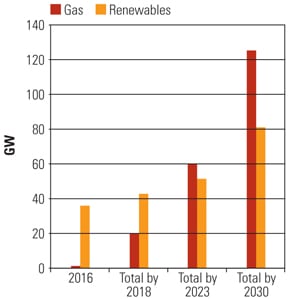

According to EIA data, natural gas capacity additions have actually fallen substantially over the past few years, even as the gas market has heated up. As can be seen in Figure 1, after reaching a peak of over 40 Bcf/d added in 2008, additions have fallen to around 14 Bcf/d in 2011.

1. Pipeline capacity additions show no sign of the growth in the gas market. Source: EIA

Capacity shortages in the Marcellus region have become so bad that the Tennessee Gas Pipeline (TGP) Zone 4 Marcellus and Henry Hub spot prices—in parity for most of early 2012—have diverged sharply in recent months, with the Marcellus price experiencing wild swings amid an overall decline. In large part, this is due to a shortage of available takeaway capacity—the gas keeps coming out of the ground, but there is nowhere to put it.

None of this is to suggest that the pipeline companies have been idle: Four major pipeline projects in the northeast region, comprising 1.5 Bcf/d, came online in 2011. The additions were able to bring Henry Hub and TGP Zone 4 Marcellus prices into parity during the 2011–2012 winter, eliminating a substantial discount that had existed. But as production continued to climb, the prices have diverged again as the newly added capacity is already overtaxed.

A Checkered Past

The roots of this problem go back decades. The natural gas pipeline and electricity markets evolved largely separate from one another, and there are significant differences in the commercial, regulatory, and operational models under which they operate. A 2011 report from the North American Electric Reliability Corp. (NERC) breaks down the key issues and history:

- An electrical generator has relatively little control over the size and location of loads on its system, while a pipeline operator typically has firm contracts in place spelling out how much gas goes where.

- Electrical grids have excess capacity built into them for reliability reasons; pipeline systems are built to serve contracted demand. “Interruptible” (that is, non-firm) pipeline service is available only to the extent that firm contracted capacity is not being used.

- Utilities can bill existing customers for capital investments in new capacity; pipeline operators are prohibited from doing so.

- The deployment of gas-fired power has been highly variable in recent decades because of significant fluctuations in gas prices, while gas pipelines have traditionally been built to serve consumers who can commit to predictable, long-term contracts.

- Day-to-day planning in the two industries operates on different schedules (local midnight-to-midnight for electric and 9 a.m. to 9 a.m. EST for gas), creating a planning gap because generators must estimate their gas needs several hours before they have finalized operational plans for the next day.

- Finally, gas moves much more slowly through a pipeline than electrons can move through a transmission line, so a pipeline operator’s ability to respond to unexpected loads is much more constrained. Sudden electrical demand can create pipeline pressure drops across an entire system, which in turn can create serious problems during peak winter usage periods.

Other, more recent developments have served to exacerbate these differences:

- The dramatic expansion of gas-fired generation capacity in the 2000s was not matched by similar growth in pipeline capacity, nor has it occurred in areas that the long-haul gas distribution system evolved to serve. Power generation has gone from the smallest consuming sector of the gas market to the largest. Interruptible service, once inexpensive and easily obtained, is now often unavailable altogether during periods of peak demand.

- The increasing contribution of wind power has added a new source of uncertainty, as gas-fired plants now need to be able to respond not just to changes in temperature but also wind. Furthermore, while temperatures change over the course of a day, wind can fluctuate up and down over a matter of minutes.

- Unexpectedly large degrees of coal-to-gas switching over the past year have meant plants built and contracted with gas supply as peaking units have been running far above planned capacity factors.

It is worth pointing out that some of these differences exist, or are exacerbated by, the regulatory frameworks that have grown up around each industry’s traditional business practices. (For more on this whole issue, see "Partners in Reliability: Gas and Electricity" in the September issue of POWER.) Though the interdependency between the gas and electric markets has forced some adjustments, such as (expensive) contracts allowing large demand swings with no notice, the consensus of industry regulators, such as NERC, is that much more work needs to be done, especially in areas that are only just now beginning to see large amounts of gas-fired power.

Collision Course?

The growing uncertainty has electric utilities increasingly worried, worries that they are making clear to the pipeline industry. At the July Natural Gas Roundtable put on by the American Gas Association, Alan Armstrong, president and CEO of Williams, reported numerous recent conversations with utility executives about their concerns with the pipeline infrastructure. Unlike coal plants that can stockpile coal on site, plants that use gas have to plan ahead. "Utilities don’t have the luxury to sit back and wait," Armstrong said.

Though the short-term problems stem from excess gas production, the long-term issues are an outgrowth of the pipeline industry’s traditional business model: Pipelines don’t get built until customers sign long-term contracts for delivery. That’s increasingly difficult to do with the growth of competitive electric markets, where substantial revenue comes from hour-by-hour sales of electricity. Poor planning and price fluctuations could put an unlucky generator in the situation of having to pay for gas it can’t use because the plant it was intended for can’t sell its electricity at competitive rates. As a general rule, traditional firm service does not make economic sense in these markets or for plants that will not be running continuously.

The pipeline industry, for its part, is well aware of the problems. “The interstate natural gas system has a long history of financing and constructing the pipeline infrastructure needed to meet its customers’ needs in a timely and cost-effective manner,” said Don Santa, president and CEO of the Interstate Natural Gas Association of America (INGAA), in a statement in June. “Still, we recognize that the gas pipeline and electric industries need to work together with regulators to address and remove any impediments to greater utilization of natural gas for electricity generation.”

FERC Acts

The continued insistence on long-term pipeline contracts in an era when long-term power purchase agreements are frequently no longer the rule is creating substantial tension between the two industries. This problem has not gone unnoticed in Washington.

In February, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) formally requested comments from the industry on ways to improve coordination between natural gas and electricity markets. The request drew a "surprisingly strong" response, FERC Commissioner Phillip Moeller said later, and 77 comments were ultimately filed by gas producers, pipeline companies, public and private utilities, state public utility commissions, independent system operators, and gas consumers across the country.

In early July, FERC announced that it would be holding a series of regional conferences on gas-electric cooperation. In FERC’s view, "The natural gas and electricity industries provide a service that is critical to health and safety in this nation. Yet recent events have illustrated why the interdependence of these industries merits careful attention. In short, this nation must ensure that outages and reliability problems are not the result of the lack of coordination between the electricity and gas industries."

Shortly afterward, on July 20, FERC released updated business standards for interstate gas pipelines that are intended to improve gas-electric coordination. The new standards take effect Dec. 1, 2012.

At the first conference in St. Louis on Aug. 6, several plant operators noted the problems with significantly different operating constraints on their gas supplies from region to region, which means they need to maintain a portfolio of pipeline services from firm commitment to no notice. Though the separation of the gas day and electric day is a challenge, they were not convinced that matching them would immediately address the basic coordination problems. "You could just be trading one issue for another," one said, though a desire to fine-tune the system was common.

Another generator pointed out that as gas replaces coal, the shift to baseload—even though demand is increased—makes fuel management more predictable. "In some respects it makes the job easier, not more challenging."

Though there was a general interest in better communication and coordination, several participants were concerned about confidentiality issues. Said Randall Van Aartsen of upper Midwest generator We Energies, "I would be reluctant to share some of that market-sensitive information, if it was something that could be used by others to their advantage."

Environmental Headaches

Not all the delays in pipeline construction have been the result of roadblocks in gas-electric cooperation. More than a few have been caused by opposition from local and environmental groups.

Inergy’s planned MARC 1 pipeline project in Pennsylvania is intended to serve as a key link from the Marcellus field to several interstate pipelines and Inergy’s storage facility in southern New York (Figure 2). Since it was first proposed in 2010, it has also served as a flashpoint for opposition to hydraulic fracturing in the Marcellus region and to the natural gas industry in general.

2. The MARC 1 pipeline project, currently under construction in central Pennsylvania, has ignited substantial opposition from local landowners and environmental groups. Courtesy: Dura Bond Industries

The 39-mile project would pass through the largely rural and undeveloped Endless Mountains area of central Pennsylvania. Opposition has centered around possible environmental damage, given that the route passes over more than 100 local streams and rivers. Last July, opponents were bolstered by a statement from the Environmental Protection Agency questioning whether the pipeline needed to built given the potential impact and other pipelines in the region. However, in November, FERC ruled that the project could proceed without a full environmental impact statement (EIS) because its initial environmental assessment indicated that the pipeline would have only "limited impact" on landowners and communities along the proposed route.

Several environmental groups, led by the Sierra Club, filed suit afterward, petitioning the Second Circuit Court of Appeals to overturn the FERC ruling on the grounds that an EIS was necessary. In June, the court found that FERC had complied with the EIS rules and rejected the petition.

The Sierra Club’s opposition to the pipeline is not purely focused on the project itself but also on the larger issues of natural gas usage. Its appeal of the FERC order was grounded in part on the alleged environmental impacts of fracking in the Marcellus region, the argument being that the new pipeline would encourage expanded drilling. (Both FERC and the Court of Appeals felt this concern was too speculative and outside the scope of the required review.)

In March, the Sierra Club announced a new initiative, "Beyond Natural Gas," in which it promises to oppose all elements of the gas industry: drilling, pipelines, power generation, and liquefied natural gas exports. This is a marked reversal of its stance from recent years, when it championed natural gas as an alternative to coal, with a project called—naturally enough—"Beyond Coal." The Club did an abrupt about-face on natural gas shortly after it was revealed that Beyond Coal was being funded in large part by more than $26 million in donations from Chesapeake Energy and others in the gas industry.

Uncertainty Ahead

FERC records show that, as of April, applications for approximately 900 miles of pipeline projects representing a total of 14 Bcf/d capacity were pending. EIA data from May, which includes expansions and projects that have not yet applied for permits, shows approximately 4,800 miles of pipeline comprising almost 50 Bcf/d capacity planned or proposed to come online by 2015.

These projects, if completed, would do much to alleviate the current bottlenecks. It is worth noting, though, that the 50 Bcf/d figure is only slightly more than what was added in 2008 alone and would represent very little growth in capacity additions over the 2010–2015 period.

The outcome of this debate will have to wait—at the very least—until FERC completes its regional conferences at the end of August.

INGAA, for its part, is sticking with its policy in favor of firm contracting and argues that it is the electric markets needing reform.

"INGAA believes FERC, together with NERC and state regulators, should establish a mechanism for determining the amount of pipeline capacity (or some other type of firm back up fuel such as oil) needed to ensure electric grid reliability," it said in June. "FERC should use this determination to reform wholesale power market rules to assign responsibility for holding such pipeline capacity and provide a means to recover the costs incurred for this purpose."

—Thomas W. Overton, JD is POWER’s gas technology editor. Follow Tom on Twitter.