How to Get the Most Out of EPC Contracts

Engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) contracts are agreements in which a contractor is given major project responsibilities under a single contract established with an owner or developer. A significant level of risk transfer characterizes these deals. This article will help you decide if an EPC contract is right for your project, and if so, how best to manage the details.

With long material lead times and a persistent construction labor shortage that is impacting the utility industry, some power project developers and owners are turning to engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) contracts—which transfer some (if not all) design and construction risk to a contractor—as a solution.

For those looking to reduce cost overruns and project delays, EPC contracts may seem like a cure-all: simply demand X, Y, and Z by a target date; set a few project milestones; and leave the rest to a third-party. Yet, many are deploying them hastily, with limited foresight and scant experience—a move that can jeopardize partnerships and cause the very same cost overruns developers and owners seek to avoid.

In what follows, I’ll outline key reasons why developers or owners might want to leverage an EPC contract, a few guiding principles that lead to successful EPC arrangements, and other contract types that power industry players should consider.

When an EPC Contract Makes the Most Sense

In an EPC contract, the contractor typically assumes risks associated with design, procurement, and construction, including workplace accidents, labor and material shortages, critical schedule milestones, and other factors that can impede project success. The tradeoff is that the developer also delegates, or turns over authority of, critical project decisions and cannot make wholesale changes to a project without amending the original contract (through what are called change orders). The cost of those change orders is often higher than if they were included in the original project scope, due to the time and effort to rework or replace completed work.

With a few caveats, this can be an attractive prospect, especially for developers who lack the financial brawn to shoulder unexpected expenses or the internal expertise to see a project through to completion—a situation in which giving up some oversight is actually a wise decision. The cost certainty this model can provide also allows developers to lock in financing and negotiate the contract’s payment schedule, thus enabling them to manage their cash flows throughout the project.

Another common use case is a utility interconnect involving a third-party independent power producer. For instance, let’s say you’re a transmission owner building high-voltage transmission lines for a large solar farm on a strict deadline. If missing that deadline results in steep financial repercussions, you can draw up an EPC contract that requires completion by a certain date and shifts responsibility for late fees to the contractor.

How to Successfully Manage an EPC Contract Project

Once developers or owners have decided on an EPC contract, they should consider the following rules of thumb to effectively collaborate with their contractors and streamline project completion.

Reduce Your Level of Engagement. Developers shouldn’t expect an EPC-based project to operate the same way as other projects on their dockets. If they maintain a similar level of involvement, they’ll have to draft change orders for every alteration, which can run up expenses and cause project delays. Developers should instead capitalize on the benefits of an EPC contract, namely, a partial hands-off approach that can save them time, labor, and resources on a looming deadline.

Developers may also consider investing in the development of design or construction standards that can be provided to EPC contractors prior to contract negotiations. These standards not only give the developer peace of mind that a project will be designed and constructed as they intend, but they can also help the developer limit their involvement throughout the design process, since they will have already provided the appropriate direction.

Use EPC Contracts to Mitigate Risk—Not Transfer All of It. While it may sound great on paper to shift all project risk to the contractor, this approach comes with a substantial premium. That’s because a contractor must factor in all known and unknown contingencies—what lies beneath the project site, for example, or worse, the possibility of another pandemic—and will price those factors into an EPC contract accordingly.

To strike better deals, developers should consider shouldering some responsibility for unforeseen circumstances that are outside of contractors’ control. For example, a developer may consider negotiating into the contract a price per unit for certain materials (steel, copper, etc.) if there is a substantial change in the quantities required. This can give a contractor reassurance that, if there is a change, they will be able to recoup the cost of the additional material (along with some profit) without the need for a prolonged change order negotiation.

Get an Outside Perspective. Developers who lack the in-house capability or bandwidth to review EPC designs should consider enlisting the services of a third-party organization, such as an engineering firm, to provide reviews on behalf of the developer or owner. It’s a safer bet to set aside a couple hundred thousand dollars for an extensive contract review when millions of dollars are at stake.

Ideally, this third-party would have no financial stake or prior involvement in the project; the company’s sole focus would be assessing whether the developer is getting the final site they specified. Developers or owners can leverage their pre-existing relationships with other engineering firms to do this. After all, these companies likely know what a particular developer expects and wants out of a project. These engineering firms can also help the developer or owner identify potential change order items prior to them occurring, so that the developer can determine the best approach for proceeding.

Expect Relationships with Your Contractors to Change. Though not always the case, most developers expect a higher price tag when using an EPC contract. Yet, few anticipate another drawback: strained relationships with contractors.

This can happen for a multitude of reasons. In a traditional time-and-material (T&M) contract, for example, a contractor may reach out to discuss project milestones, targets, or ideas about how to best move a project forward. In contrast, an EPC contractor usually calls a developer or owner to request additional funds, which can strain even the healthiest of partnerships as time goes on. Unfortunately, EPC contractors have a greater incentive to get projects finished on schedule and under budget than to make friends with developers or owners.

This dynamic can be particularly troubling if a developer or owner had a strong relationship with a contractor prior to deploying an EPC contract. Unfortunately, outcomes like these are difficult to avoid—so developers in this situation should consider limiting the use of EPC contracts to specific project types.

Alternatives to Traditional EPC Contracts

There is no one-size-fits-all contract for construction in the power industry. Developers who are drawn to specific aspects of EPC contracts, but wish to remain involved in project design and construction, should also consider the following options.

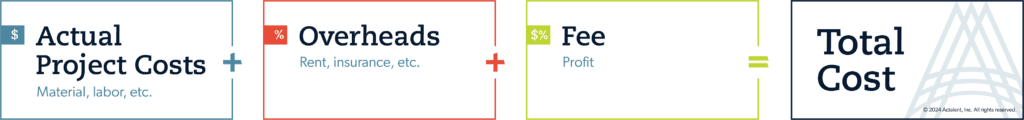

Cost-Plus Contracts. This arrangement (Figure 1) allows contractors and developers to negotiate the appropriate percentages used to cover the contractor’s overhead costs and profit, while providing reassurance to the contractor that all project costs will be paid.

|

|

1. What is a cost-plus contract? Courtesy: Actalent |

By taking this approach, developers can get insight into how an EPC contract works, but still maintain hands-on involvement and final approval in a construction project. Say, for instance, a contractor is seeking subcontracts and garners three bids. One of those bids is from a subcontractor that the developer feels has poor craftsmanship. Under a traditional or fixed price EPC contract, the developer cannot compel the contractor to select one bid over the other, whereas, in a cost-plus contract, the developer can. Since the developer will be paying the higher cost, the contractor isn’t financially incentivized to simply pick the lowest bid.

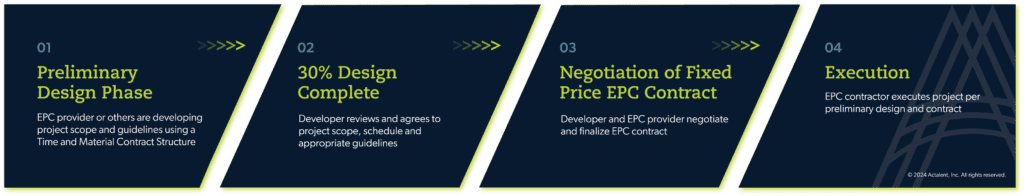

Hybrid EPC Contracts. Some developers have taken a hybrid approach (Figure 2) to crafting EPC contracts, in which the first 30% of a project design is treated as a T&M contract. This means that contractors bill an hourly rate, while developers provide input throughout the development process. Marked by an iterative process of design, this approach is flexible and often requires fewer change orders. But once the project has reached 30% completion, contractors deliver developers a fixed price to finish the project. Developers or owners that are interested in EPC contracts tend to welcome hybrid EPCs conceptually, as many unknown risks are ironed out in the beginning stages of the project.

|

|

2. Engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) contracts: Using a hybrid process. Courtesy: Actalent |

Hybrid EPCs can be a good fit for many developers due to their ability to finalize these unknown risks in the beginning stages of the project. However, they risk getting over-involved after responsibility for the project has shifted to the contractor. Since engineers and other team members often establish collaborative relationships with contractors early on, this can be an easy trap to fall into.

I’ve also encountered developers who, in the later phases of a project, have tried to make sweeping changes—not to amend design flaws, but to align the final product more closely with their preferences. By that point, construction workers have likely begun site grading and pouring concrete, and moving a single piece of equipment can require a complete teardown and rebuild. In this model, the cost for this teardown is covered by the developer since the change was identified after the design was agreed to at the 30% stage. Last-minute moves like these can cost tens of thousands of dollars on a fixed price EPC contract—and many developers become frustrated upon discovering they must pay extra for what they want.

Unfortunately, once developers lock in a price, they essentially give up the right to change their mind without expecting an associated change order for that change. For that reason, they should probably have substantial experience with EPC contracts before jumping into a hybrid arrangement.

EPC Contracts Can Be a Powerful Tool

As industry challenges continue to mount, knowing how, why, and when to deploy an EPC contract can save developers time, money, and headaches. While EPC contracts offer specific advantages, it’s essential to address the specific needs and characteristics of a given project. Ultimately, a developer has to be willing to give up some level of control. With proper preparation, power project developers can make strategic contractual decisions that lead to project success.

—Ryan Cross is senior energy practice manager at Actalent.