Financial and Gas Turbine Blade Troubles Plague GE Power

GE Power’s financials spun out further on a dismal trajectory during the fourth quarter of 2018, plagued by slack market demand for products and services, technical glitches of a flagship gas turbine model, and poor project execution.

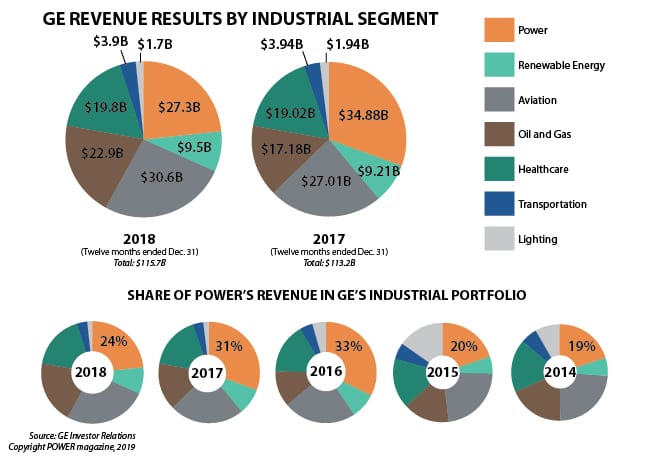

Despite a series of divestments and corporate reshuffles, including of leadership, for the 12 months that ended on Dec. 31, the conglomerate’s Power division recorded revenues of $27.3 billion—22% lower than in 2017, when it first unveiled weak earnings associated with its underperforming $10.1 billion acquisition of Alstom’s Power and Grid business.

For the fourth quarter of 2018, GE said on Jan. 31 revenues for the beleaguered division fell to $6.8 billion—25% compared to the fourth quarter of 2017, but $1 billion higher than in the third quarter of 2018. The business incurred a loss of $872 million primarily related to “continued execution and operational issues on equipment projects and transactional services.”

In an earnings call with investors on Jan. 31, H. Lawrence Culp Jr., who was appointed last October at the conglomerate’s helm to replace John Flannery, lauded GE’s global reach, brand, talent, and long-term customer relationships. But the dismal results had prompted intense scrutiny of every aspect of the Power business, he said. “For Power, we are resetting the baseline. We are reviewing every single project and contract and digging deeper to understand costs and benefits with respect to restructuring, market and commercial execution, improvement opportunities, legacy project issues, and our service operations.”

The efforts, he said, are providing the company with “more meaningful insight into the paths for near and long-term earnings and cash potential of this business.” However, “the work takes time, especially with the new structure and leadership team,” he said.

A Diminished Division

The past two years, in particular, have been transformative for GE, owing largely to worries about revenue misses at Power, the conglomerate’s long-standing and lucrative segment. Power’s combined businesses, along with the company’s Aviation business, have historically raked in the most revenues for the 127-year old company. Last year, the Aviation business charged ahead of Power after a two-year lull, fueled by a surge in orders for LEAP engines and military equipment.

In 2015, the company marked a major milestone as it took over competitor Alstom in a $10.1 billion deal, and integrated the giant global equipment firm’s products and services into its portfolio. And the year before, it launched the HA heavy-duty gas turbine, a new gas turbine technology that GE’s engineers leveraged to achieve a 62.22% combined cycle net efficiency (at EDF’s Bouchain plant in 2016 with a 9HA.01 unit) and 63.08% combined-cycle gross efficiency (at Chubu Electric Power’s Nishi Nagoya plant in 2018 with a 7HA.01 unit).

But cracks in the business were already beginning to show by the end of 2016. GE Power began to shed lucrative assets, framing them as sound business decisions to encourage cash flow. At the same time, GE shook up its leadership, replacing 40% of its executive team, and putting John Flannery at the company’s helm in August 2017 to replace Jeff Immelt, who had been GE’s CEO for 16 years.

At the end of 2017, citing disruptions that were dramatically reshaping the power landscape globally and underperformance of Alstom’s acquired assets, the company signaled GE Power was “challenged” by a “tough market.” Flannery told investors in a November 2017 call that GE had “exacerbated the market situation with some really poor execution.” Russel Stokes, who replaced Steve Bolze as president and CEO of GE Power, then said GE Power’s challenges were rooted in shaky optimism about customer gas turbine utilization and upgrades. Stokes pointed to recent electricity market changes, and initial launch issues for the HA product, for the blow to earnings.

The company immediately embarked on a strong revamp effort to shrink costs. Over 2018, GE Power shed 10,000 jobs—15% of the conglomerate’s total workforce. It also moved to consolidate its footprint by 30% and eliminated $900 million in base costs.

Despite its efforts, the company’s stock price continued to wane through early 2018, and the company received a slap in the face in June when it was removed from the prestigious Dow Jones Industrial Average; GE had been the last original member of the 1896-created blue-chip index, and had continuously been a member since November 1907.

Then, on Oct.1, GE announced that Culp had been named chairman and CEO to immediately replace Flannery. GE’s board of directors voted unanimously on the decision. In a press release announcing the change, GE specifically cited weak performance in the GE Power business for a shortfall in free cash flow and earnings in 2018, suggesting other businesses were generally performing as expected.

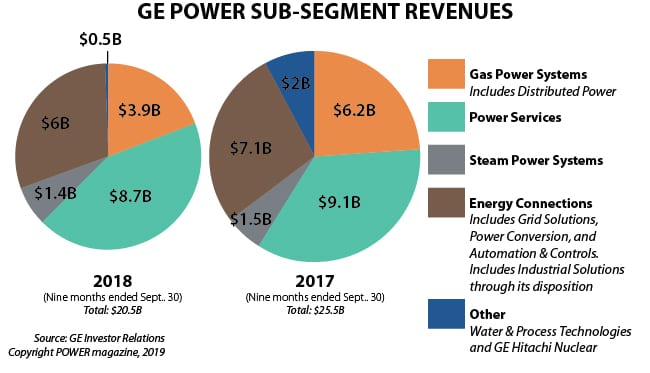

On Nov. 19, the company announced another substantial shakeup at GE Power. The division, freshly stripped of Distributed Power, Water and Process Technologies, Industrial Solutions, and Automation Solutions (see sidebar, “GE’s Power Business Transformation”)—segments that brought in more than $4 billion in revenues in 2016—had been cleaved into two businesses. These are: “GE Gas Power,” composed of GE’s Gas Power Systems and Power Services segments; and “GE Power Portfolio,” which comprises the Steam, Grid Solutions, Nuclear, and Power Conversion segments.

Along with the split came new leadership. Stokes, a 20-year GE veteran and GE Power’s former CEO became CEO of GE Power Portfolio, while Scott Strazik, formerly president of Power Services, was named CEO of the GE Gas Power business. Meanwhile, John Rice, who served at the helms of GE Energy, Transportation, and other divisions before he retired after a 39-year tenure at GE, returned to serve as chairman of GE Gas Power. “The leaders we are announcing today are exceptionally well suited to lead our new Gas Power and Power Portfolio teams in their efforts to deliver better customer outcomes and improve their execution and cost structures,” Culp said in a statement at the time.

In January, meanwhile, GE announced the Renewable Energy business—which reported revenues of $9.5 billion for 2018 (up 4% for 2018 and 28% in the fourth quarter, compared year-over-year)—would absorb GE Power’s Grid Solutions segment, along with sub-segments associated with solar solutions and energy storage.

GE’s Power Business TransformationThough it has been reshaped by countless acquisitions and divestments, GE’s power business has been a flagship name in the global power generating business since 1896, when it became one of the first companies listed on the then newly formed Dow Jones Industrial Average. By 1901, GE had successfully developed a 500-kW Curtis turbine generator, and in 1948, it installed a pioneering heavy-duty gas turbine for power generation at the Belle Isle Station in Oklahoma. Then in 1957, the company connected the first nuclear reactor to a commercial electricity grid. GE’s contributions to power generation technology have continued in a steady stream over the years. A decade ago—as the company’s financial unit flailed during the global financial crisis (and GE famously reached out to Warren Buffet, who made a crucial $3 billion investment to keep the company afloat)—GE’s power businesses were grouped under GE Energy, a division headquartered in Atlanta. In 2010, GE Energy, which in 2009 generated $37.1 billion in revenues, was split into three businesses: GE Energy Services, which included grid-related businesses, power services, industrial solutions, and parts and repair; GE Power & Water, which included its full array of power generation and delivery technologies, including its gas and steam turbines, renewable energy, and nuclear energy (GE Hitachi Nuclear Energy, a joint venture with Hitachi); and GE Oil & Gas, which housed its segments catering to the oil and gas production industry. On Nov. 2, 2015, GE completed the $10.1 billion acquisition of Alstom’s Thermal, Renewables and Grid businesses. Following the deal, GE separated its renewables business and moved the headquarters of the newly created Renewable Energy segment to Paris. Alstom’s gas and steam businesses were absorbed into GE Power and Water. At the end of 2016, GE Power was composed of the following segments: Gas Power Systems, Steam Power Systems, Power Services, Distributed Power, Water & Process Technologies, GE Hitachi Nuclear. Beginning in the third quarter of 2017, the Energy Connections business—and its grid-related businesses—within the former Energy Connections & Lighting segment was combined with the Power segment and presented as one reporting segment called “Power.” The Lighting business became its own segment. In mid-2017, weakened earnings—associated in part with the Alstom acquisition—prompted the giant conglomerate to rejigger its power business and lean more heavily on other segments. To encourage cash flow, GE Power made hard choices and began a series divestments: Sept. 2017: GE Power announced the sale of GE Industrial Solutions—GE’s global electrification solutions business—to ABB for $2.6 billion. The transaction was completed in June 2018. October 2017: GE completed the $3.4 billion sale of the lucrative Water & Process Technologies segment to water management firm SUEZ. July 2018: GE moved to sell its Distributed Power business, which included the company’s Jenbacher and Waukesha engines, to Advent International, a global private equity investment company, in a deal worth $3.25 billion. The company became a stand-alone energy company rebranded as INNIO when the deal was completed in November 2018. Oct. 2, 2018: Emerson announced it would acquire Intelligent Platforms, which was part of GE Power’s Automation & Controls sub-segment. The deal was completed on Feb. 1. The Charlottesville, Virginia—based company, specializes in programmable logic controller (PLC) technologies. GE has since strategically placed other portions of the Automation and Controls segment into Steam Power Systems, Gas Power Systems, and Grid Solutions. Oct. 30, 2018: Weeks after GE introduced newly appointed GE Chairman and CEO H. Lawrence Culp Jr. to replace John Flannery—and announced it expected to take a non-cash goodwill impairment charge of about $23 billion related to the GE Power business—GE announced it planned to divide GE Power into two units: GE Gas Power, which is composed of Gas Power Systems and Power Services; and GE Power Portfolio, comprising Steam Power Systems, Grid Solutions, GE Hitachi Nuclear, and Power Conversion. January 2019: GE announced it would transfer Grid Solutions to GE Renewable Energy. The renewables and grid consolidation would create a $16 billion business with 40,000 employees. GE’s Renewable Energy division had previously employed about 23,000 workers. As of the end of 2017, GE had a total 313,000 employees, about 83,500 of which were affiliated with the Power division. |

Assessing the Damage

In a Jan. 31 earnings call with investors, Jamie Miller, GE senior vice president and chief financial officer, delivered GE Power’s dismal results stoically. Orders for GE Power were down 19% for the fourth quarter. Gas power system orders fell much more dramatically—by 26% for the quarter and by 40% for the year. She said GE ended 2018 with a $9 billion backlog, which was down around 8% year-over-year, but that result was said to be consistent with the company’s outlook. Power services orders also fell by 20%, and grid orders fell 13% for the year. However, she noted, steam orders were up 61%.

The revenue picture was as gloomy. GE hemorrhaged $400 million in charges related to its contractual service agreements (CSA) during the quarter, which further battered the division’s revenues. Those charges, Miller said, stemmed from a critical oxidation issue that affects the lifespan of a single blade component in the first generation of GE’s advanced HA gas turbines.

That issue first came to light in the media last September after a blade broke at Exelon’s 1,088-MW Colorado Bend station in Texas, a facility that began commercial operations in June 2017 equipped with two 7HA combined cycle gas turbines. Three days later, French utility EDF shut down the Bouchain facility—an HA facility that touted the turbine technology’s groundbreaking efficiency when it came online in 2016—to replace blades. Reuters reported on Jan. 25 that Japan’s Chubu Electric learned about the blade issue in October and had since restricted operation time at one of its two HA units for blade replacements, which it expected would be concluded at the end of this month. Several other HA gas turbine owners around the world appear to be affected.

Reuters, which cited two separate GE presentations it had reviewed, reported that GE became aware of a similar blade issue with the GE 9FB turbine—an HA predecessor, and a GE legacy turbine model that it said comprises less than 1% of GE’s global gas turbine fleet—after a blade broke in 2015 at an undisclosed power plant, prompting the company to work on new protective coatings and alter a heat treatment for the parts. “The HA components were in development before the initial 9FB issue occurred, and the HA units began to ship while the root-cause analysis was in process and before it was determined that it was a component issue that impacted the 9FB fleet and the HA,” GE said in a statement to Reuters.

GE is now replacing blades in about 50 9FB and 52 HA turbines.“We are executing the plan we laid out to fix the issue,” a GE spokesperson told POWER on Feb. 6. “The feedback from customers has been positive, and they continue to choose the HA, which remains the fastest growing fleet of advanced technology turbines in the world today,”

Last week, Miller said that the $400 million in charges related to the turbine debacle includes service costs, such as for overtime. In the third quarter, GE also took a hit of $240 million of warranty and other accruals related to the blade issue, she noted. Culp, meanwhile, suggested that the company’s blade troubles are ongoing. Costs related to the issue are “really a function of going out and effectively replacing these blades sooner than we were anticipating … because the useful life is effectively shorter than we had anticipated, unfortunately,” he said last week.

While costly, the blade issue is just one of a handful of banes at GE Power. GE also incurred $350 million in costs related Gas Power System projects. “Similar to the third quarter, we continue to experience project execution issues resulting in liquidated damages as well as partner execution issues,” Miller said. The outlook isn’t much brighter. “[O]verall, we see the heavy duty gas turbine market as flat over the next few years and see significant opportunity to improve our own execution,” she said.

A Fog of Disruption

According to Culp, the much-leaner Power division’s “underperformance” was rooted in several causes—mainly that the company’s outlook had previously been obscured by the fog of disruption, he suggested.

“First, as I said last quarter, we were late to embrace the realities of the secular and cyclical pressures in the business,” Culp said. “Recent data suggest that the market for new generating capacity is settling in to the 25 to 30 GW range for the foreseeable future. We continue to believe gas will play an important role in global electrification, but we have to resize our cost structure, our capital expenses and our supply chains to this new reality now.”

GE will need to stay grounded, he said. “Embracing market reality means a more appropriate revenue outlook, one that is further grounded in the reality of our $92 billion backlog rather than in the hope of new orders not yet won.”

The Power business also faces “a number of nonoperational headwinds,” Culp noted. “These include legal settlements and legacy project erosion, principally driven by the Alstom acquisition. There’s also the runoff of the effects of past long-term receivables factoring and other programs.” Culp appeared optimistic about resolving these issues. “Over the next few years, these effects should come down substantially,” he said.

Echoing Miller’s sentiments, better execution at the Power business was also warranted, and that effort will require “improved daily management in how we sell, make, and service our products,” Culp said. GE Power, for example, previously had separate teams of managers commissioning new plants, owning the warranty period, and overseeing service contracts after the warranty.

“Now we present one face to the customer, who is accountable for the best long-term economic answer, both for the customer and GE. We put the sales organization under one leader with deep domain expertise and we are coordinating better on contract negotiations. We now have more experienced people owning negotiations and responsible for project cost.”

GE is also streamlining contracts. “We performed risk assessments of our existing 400 equipment contracts to identify cost and execution risks. We also performed a similar assessment on the 750 CSA contracts to identify price and utilization risk. We have overhauled our commercial underwriting processes to set more realistic commitments and returns from the start.” Those efforts so far have identified $400 million in charges

Tackling these “root causes” would take time, “but we are improving, and I’m confident that those changes will come,” he noted. GE Power’s customers, too, are confident, he said.

“They’re rooting for us. They want us to succeed, and they want to know how they can help.”

—Sonal Patel is a POWER associate editor (@sonalcpatel, @POWERmagazine)

Corrected (Feb. 7): This version corrects numbers in the third paragraph to reflect GE’s Power business generated revenues of $6.8 billion, and updates percentages to reflect comparisons year-over-year, not by quarter as originally stated. In the third quarter of 2018, Power generated $5.7 billion.