Eavor’s Geretsried project marks the first time a closed-loop geothermal system has delivered electricity to a commercial power grid, demonstrating a new pathway for advanced geothermal deployment.

Calgary-based Eavor Technologies on Dec. 4, 2025, became the first company to deliver electricity to a commercial power grid at its Geretsried facility in Bavaria, Germany, using a fully closed-loop geothermal system. The achievement marks what the company calls the world’s first operational deployment of multilateral “Eavor-Loop” wells, which are designed to generate continuous heat and power without fluid interaction with underground formations.

The milestone is significant because it represents the first commercial-scale proof that closed-loop geothermal—using sealed, pump-free, conduction-based well circuits rather than fluid exchange with underground formations—can reliably deliver continuous electricity and heat with high capacity factors across a wide range of geologies.

According to Eavor, the Geretsried project demonstrates a development pathway that removes many of the industry’s historic barriers, including exploration risk linked to reservoir permeability, water sourcing and treatment requirements, and the potential for induced seismicity associated with fluid injection. By decoupling geothermal power production from hydrothermal resources, the closed-loop approach positions the technology as a dispatchable, carbon-free energy option scalable beyond traditional geothermal markets, it says.

“The technological and commercial success at Geretsried validates the project as a blueprint for wider European and global rollout as regions seek stable, locally derived carbon-free energy sources with minimal land and water usage,” Fabricio Cesário, head of project delivery and operations at Eavor GmbH said in December.

A Big Leap for Advanced Geothermal Systems

For most of its commercial history, geothermal power has been dominated by conventional hydrothermal systems limited to geological settings that combine high subsurface temperatures, naturally permeable formations, and producible geothermal fluids capable of sustained circulation. Viable sites are typically concentrated in tectonically active or volcanic provinces and typically require reservoir temperatures of 150C or greater to support commercial power generation. But beyond these limitations, geothermal deployment has remained constrained by drilling risk, uncertain reservoir productivity, water sourcing demands, and regulatory scrutiny tied to pressure-management and fluid-injection practices used to sustain output.

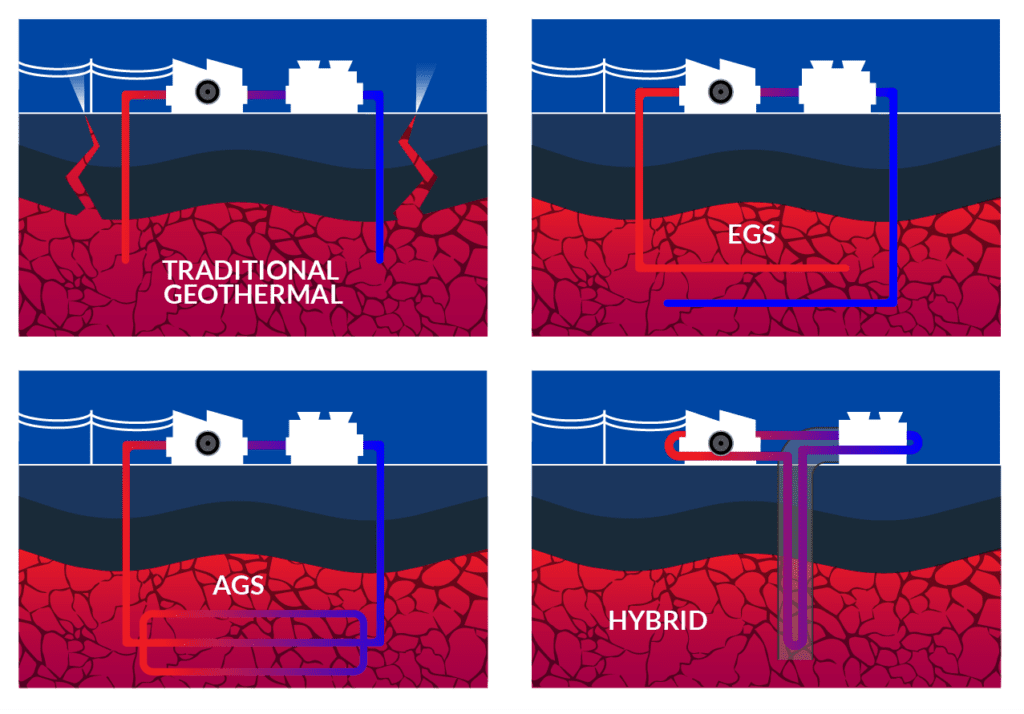

In response to those constraints, industry and government research programs have increasingly pursued engineered geothermal approaches. Enhanced Geothermal Systems (EGS) attempt to overcome low natural permeability by injecting high-pressure fluids to hydraulically stimulate hot rock formations and create artificial reservoirs for heat exchange. Still, despite decades of research—at early pilots at Fenton Hill in the U.S. and projects in Switzerland, South Korea, France, and Australia—EGS commercialization has been hindered by complex drilling and completion requirements, difficulty establishing stable, long-lived reservoir volumes capable of sustained flow, and public concerns over induced seismicity tied to subsurface stimulation.

Over the past several years, research and commercialization efforts have increasingly shifted toward Advanced Geothermal Systems (AGS), a class of technologies defined by the International Renewable Energy Agency as “deep, large, artificial closed-loop circuits in which a working fluid is circulated and heated by sub-surface rocks through conductive heat transfer.”

Like Eavor, San Francisco-based GreenFire Energy is commercializing its GreenLoop system, which retrofits idle geothermal wells with a downbore heat exchanger to harvest heat without extracting fluid. The company in May 2025 launched its first commercial geothermal demonstration at the The Geysers in California, retrofitting a low-output well with its GreenLoop downbore heat exchanger. The company reports that the system achieved sustained flow rates of 300–350 gallons per minute at 310F, completed two seven-day production tests plus step-change testing in forward/reverse flow, and is nearing completion of an industry-standard steady-state test. The California Energy Commission–funded project demonstrates high-performance power from a closed-loop system that preserves reservoir water mass. The company is now targeting 150 MWe of capacity by 2030.

Meanwhile, Houston-based Sage Geosystems is pursuing a geopressured geothermal approach that creates a sealed, fractured reservoir in hot dry rock for both power generation and long-duration energy storage. Sage’s 3-MW/4-6 hour Pressure Geothermal pilot—developed under a land-use agreement with San Miguel Electric Cooperative in Christine, Texas—moved from funding approval to “ready to store” in just 12 months, completing drilling, fracture stimulation, and surface facilities by August 2025. The system achieves 70–75% round-trip efficiency by pressurizing a subsurface fracture that pushes water through a Pelton turbine, with less than 2% water loss and digital automation for real-time ERCOT integration. The project was a POWER 2025 Top Plant.

Unlike EGS, notably, AGS designs do not rely on reservoir stimulation or fluid injection into geologic formations. Instead, they employ sealed well circuits that collect heat primarily through direct conductive contact with surrounding rock, potentially reducing seismic risk and water use requirements while enabling projects to be developed across a much wider range of geologic settings. Historically, however, AGS systems have faced engineering barriers linked to ultra-long wellbores, the need for precise multilateral intersections deep underground, and the overall economics of drilling-intensive construction.

That’s why Geretsried’s first commercial power represents a notable leap. As the first commercial deployment of an AGS system to clear those technical and operational hurdles at grid scale, “we’re more confident than ever that our closed-loop geothermal system, designed for adaptability and suited to the world’s diverse regions, will secure its place as the leading solution for commercial geothermal applications,” said Eavor President and CEO Mark Fitzgerald.

For a deeper technical breakdown of how closed-loop geothermal systems differ from Enhanced Geothermal Systems (EGS) and supercritical geothermal concepts, see POWER’s explainer, “EGS, AGS, and Supercritical Geothermal Systems: What’s the Difference?”

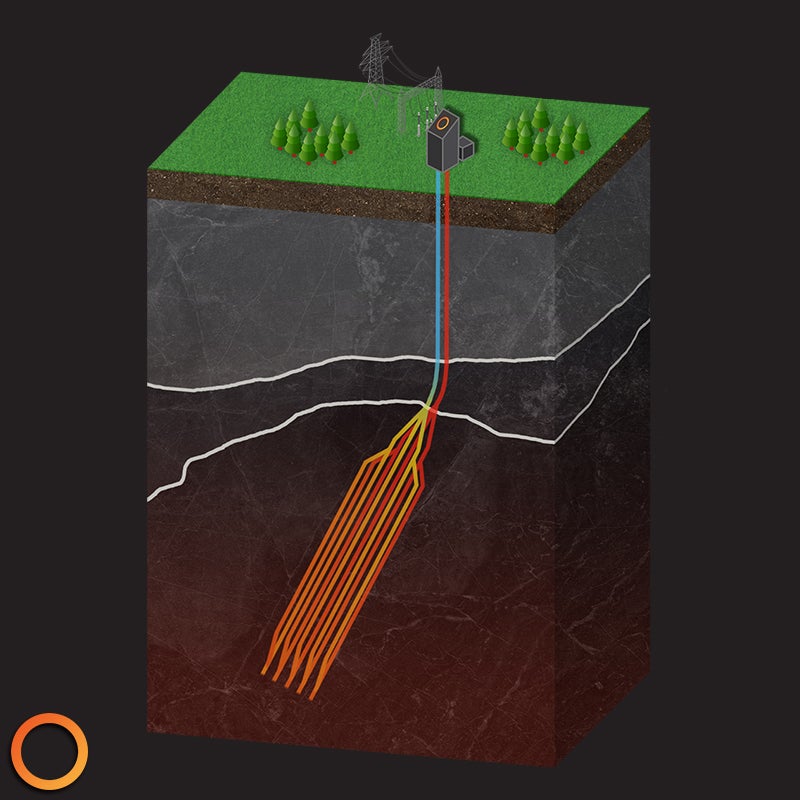

How the Eavor-Loop WorksAs Eavor explains, its closed-loop system applies precision multilateral drilling to construct long, sealed heat-exchange circuits that maximize conductive contact with hot rock while circulating a contained working fluid internally, without interaction with subsurface water or dependence on natural rock permeability. “The Eavor-Loop at Geretsried involved drilling two vertical wells and sidetracking six horizontal wells from each (a total of 12 lateral wells),” Eavor noted. “The laterals were connected toe to toe underground with the help of Eavor’s active magnetic ranging tool (AMR), creating six pairs to form a massive subsurface radiator. These wells represent some of the longest in the world, at a length of 16 kilometres of continuous wellbore per pair.” At its core, the Eavor-Loop operates as a closed geothermal heat-exchange circuit in which a sealed working fluid circulates through the paired vertical wells and extended horizontal laterals, absorbing thermal energy conducted from the surrounding rock and transporting it to the surface for conversion to electricity or delivery into district-heating systems. Eavor notes that “the working fluid in the Eavor-Loop circulates the geothermal heat to the surface,” while flow is sustained because “due to the difference in density between the warm and cold working fluids, it circulates independently in the Eavor-Loop plant,” eliminating the need for continuous pumping. The uncased laterals are “completely and permanently sealed off from the surrounding rock by a patented seal (Rock-Pipe),” ensuring that “deep water is not exchanged and no pressure is exerted on the substrate,” and eliminating induced-seismicity risks associated with reservoir-stimulation methods.

The long-term viability of the Eavor-Loop is rooted in its reliance on conductive heat transfer and the immense thermal mass of surrounding rock formations. As the company explains, “the Eavor-Loop uses conduction instead of convection to retrieve heat from below the earth’s surface,” with wells “in direct contact with hot rock so as cold fluid moves through the system that direct contact transfers heat from the hot rock to the fluid constantly via conduction.” Because “the rock also has a much higher thermal mass than the circulating liquid,” the company explains that “a one degree temperature gain in the fluid corresponds to a much smaller drop in average rock temperature.” Although heat is withdrawn from the immediate rock interface, “that heat is constantly replenished from the outer layers of rock,” resulting in long-term stability such that “the heat production rate of the Eavor-Loop remains nearly constant for over 30 years.” Thermal longevity is preserved through lateral well spacing designed to avoid interference, which Eavor describes as drilling wells “far enough apart so as not to affect the heat draw of each well significantly,” a practice known as “avoiding thermal interaction.” Engineers calculate available thermal energy using reservoir heat-capacity formulas and assess site economics by comparing recoverable heat output to drilling and construction costs. |

From Technical Validation to Commercial Power

Eavor’s first power milestone follows a decade of development, which unfolded through a multi-stage technical validation program. The company first demonstrated core thermosiphon circulation and sealed-loop drilling concepts at its Eavor-Lite prototype facility in Rocky Mountain House, Alberta, which began operations in 2019. The pilot, which comprised two vertical wells connected by 1.7-kilometer (km) multilateral laterals at a depth of 2.4 km, demonstrated “the ability to drill and intersect wells, seal and pressure-test the Rock-Pipe completion system, and validate thermodynamics.” Field results, which showed system performance within 0.5% of model predictions, provided the first real-world confirmation of Eavor’s conductive heat-transfer modeling, the company said.

As its next step, Eavor launched its Eavor-Deepdrilling program in New Mexico, where it drilled one of the world’s deepest and hottest multilateral geothermal wells, reaching a total vertical depth of more than 5,000 meters in granite formations exceeding 200C. That program validated insulated drill pipe performance, Rock-Pipe sealing in hard crystalline rock, precision multilateral intersections, and high-temperature downhole measurement-while-drilling electronics. Those achievements allowed the company to check off milestones that it suggests unlocked full-scale system engineering, helping to bolster follow-on investment from partners including bp and H&P Drilling.

Eavor then moved into full commercial execution at Geretsried, where construction began in October 2022 and drilling began in July 2023. The project is deploying four Eavor-Loops configured for combined heat and power service (64 MWth and 8 MWe) to supply the local municipality. While the site had originally been developed as a conventional geothermal project, it was abandoned after encountering hot, dry rock lacking sufficient natural permeability. The project, notably, was backed by a €91.6 million European Commission Innovation Fund grant, alongside Germany’s Renewable Energy Sources Act (EEG) feed-in tariffs of roughly €250/MWh. Completion of the on-site Organic Rankine cycle power plant and commissioning milestones through late 2024 ultimately enabled first power delivery to the grid in December 2025.

In an October 2025 white paper released at the recent Geothermal Rising Conference, Eavor said drilling at Geretsried has already pushed closed-loop geothermal down the cost and performance curve, documenting a “50% reduction in drilling time per lateral and 3x improvement in bit run lengths, thanks to iterative designs and operational improvements.” The company attributed those gains to enabling technologies including Insulated Drill Pipe (IDP)—“a critical tool for adapting existing oil and gas directional tools to perform in hotter and harsher geothermal environments”—its Eavor-Link Active Magnetic Ranging (AMR) system, which “reduced the time dedicated to wellbore intersection and ranging activities by more than 80% compared to conventional wireline methods,” and its Rock-Pipe sealant, which it used to seal the open-hole laterals and “reduc[e] well construction costs by over 40% compared to cemented casing.”

“The advancements and lessons learned at Geretsried are translating into a competitive Levelized Cost of Heat (LCOH) along with a significant increase in energy output potential for future projects,” said Jeanine Vany, co-founder and executive vice president of corporate affairs at Eavor. “Coming down that initial learning curve and proving the technology at Geretsried provides additional confidence for Eavor-Loop to scale globally as a source of reliable, flexible, carbon-free energy. These advancements bring Eavor closer to fulfilling our mission of enabling local clean energy autonomy, everywhere.”

—Sonal Patel is a national award-winning multimedia journalist and senior editor at POWER magazine with nearly two decades of experience delivering technically rigorous reporting across power generation, transmission, distribution, policy, and infrastructure worldwide (@sonalcpatel, @POWERmagazine).