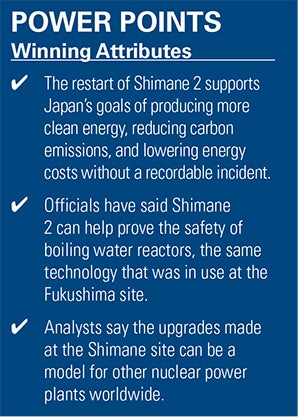

The Unit 2 reactor at the Shimane nuclear power station resumed operation in January 2025, more than a decade after it, and all other reactors in Japan, were taken offline. Japanese officials want restarted nuclear units to help supply needed power and lower the cost of energy across the country.

Japan’s restart of its nuclear fleet following the March 2011 Fukushima disaster has moved slowly. The country had 54 operating reactors at 17 plants prior to the tsunami that devastated the Fukushima plant. To date, officials said just 14 of those reactors have restarted, as Japan has instituted a rigorous safety inspection and licensing process under the auspices of local governments and the country’s Nuclear Regulation Authority (NRA).

The NRA was established in 2012. The agency has oversight of Japan’s nuclear power program, and is working with operators of the country’s reactors as officials again look at nuclear power to meet energy demands and support climate goals. The nuclear power shutdown increased Japan’s reliance on imported fossil fuels, significantly increasing energy costs and carbon emissions.

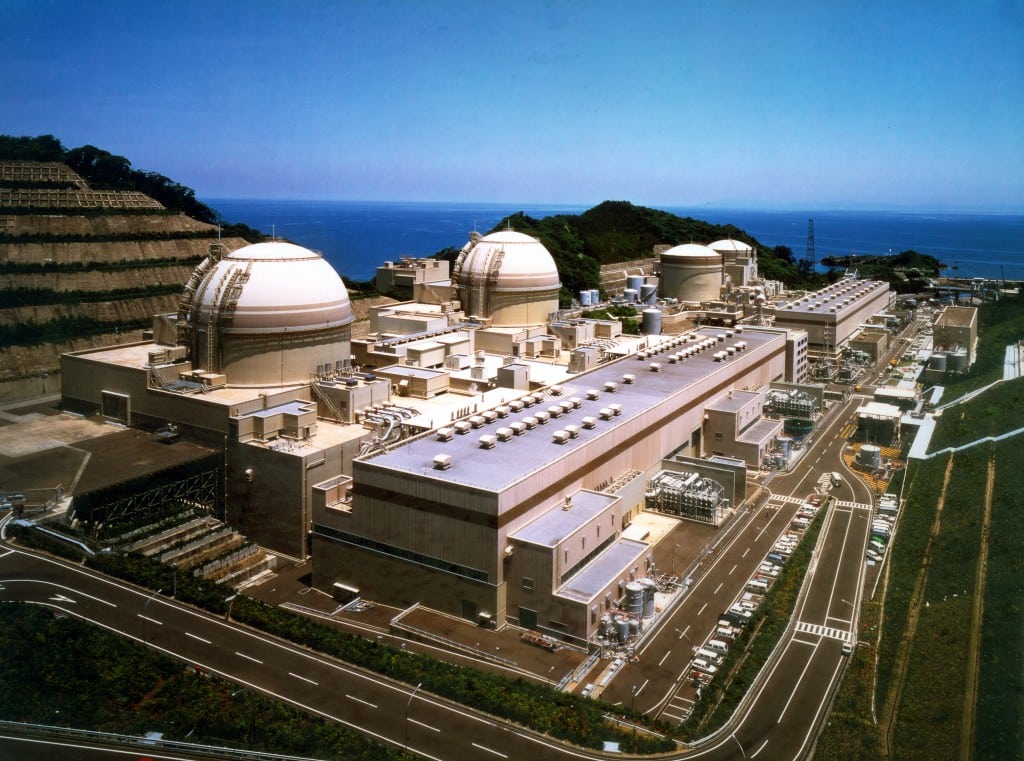

Unit 2 at the Shimane nuclear plant re-entered commercial operation in January of this year, with Japanese officials saying it was the 14th reactor to be brought online as part of the restart program. Shimane 2, with 820 MW of generation capacity according to Chugoku Electric Power, the plant’s operator, is significant because the reactor—along with Unit 2 at the Onagawa plant—is one of the first two boiling water reactors (BWRs) to be restarted. The BWR is the same technology used at Fukushima.

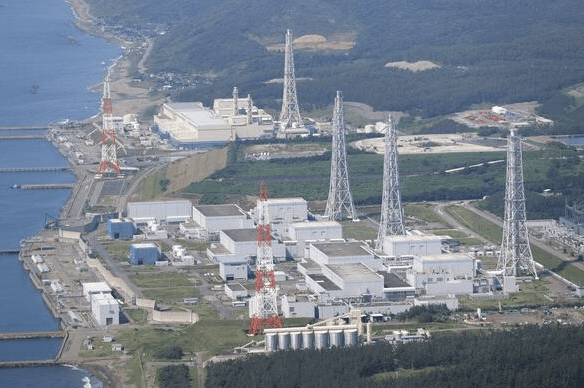

Shimane is located near the city of Matsue in southwestern Japan. The plant is the only one in Japan located in a prefectural capital, and nuclear analysts have said it is evidence of the confidence Japanese officials have in the restart program.

“Shimane 2’s restart is particularly significant because it’s only the second BWR, the same design as Fukushima, to return to operation. This demonstrates that even the most scrutinized reactor designs can meet modern safety standards, which sends a powerful message to the global nuclear community,” said Kevin Kong, CEO and founder of Everstar, a New York-based startup company building artificial intelligence (AI) solutions to accelerate nuclear energy. Kong noted, “The 11- [to] 12-year review timeline for many Japanese restarts highlights a fundamental challenge for nuclear globally: how do we maintain rigorous safety standards while avoiding regulatory processes that make projects economically unviable? Japan is finding that balance, and the industry should study what’s working.”

Francois Le Scornet, president and cleantech and climate tech senior consultant at Carbonexit Consulting, a France-headquartered energy market intelligence group, told POWER: “Japan’s nuclear restart program is progressing in a slow way, shaped by the lessons of the Fukushima event… the Nuclear Regulation Authority has required each plant to comply with very strict safety standards that include new tsunami barriers, reinforced seismic protection, filtered venting systems, or independent emergency control centers, to name a few.”

Le Scornet noted that “each reactor restart always depends on local government consent, but it seems that attitudes are gradually changing as communities see nuclear energy as a ‘stabilizing’ force in view of the current high fuel costs and climate constraints.” He added, “Overall, I believe the recent return of Shimane 2 illustrates a more confident phase. This reactor resumed its commercial operation last January, after nearly a decade of safety and seismic upgrades. Shimane 2 can be seen as a quiet symbol of Japan’s ‘nuclear reset,’ showing that engineering upgrades and transparent communication can gradually rebuild trust. I think that while public opinion remains mixed, Japan’s step-by-step approach is quite successful.”

Shimane’s History

Unit 1 at Shimane, with 439 MW of capacity, was commissioned in 1974 and operated until it was decommissioned in 2015. Unit 2 first came online in 1989, and was taken offline in January 2012—meaning it was shut down for 13 years before being restarted.

A third unit at Shimane was expected to enter service in 2012, but construction was suspended due to the nuclear halt. Unit 3 would be an advanced boiling water reactor, with generation capacity of 1,373 MW, which would make it one of the largest reactors in terms of output in Japan should it be completed. The World Nuclear Association recently said at least 11 more reactors are in the process of being approved to restart. Japanese officials also are looking at deploying small modular reactors.

“Japan’s renewed commitment to nuclear—targeting 20% of generation by 2040, reflects the reality that energy-importing nations face stark choices in an era where decarbonization and energy security are national security imperatives,” said Kong. “These existing reactors are the best bridge to a clean energy future that will eventually include next-generation advanced reactors. You can’t power a modern industrial economy on intermittent renewables alone, and with global energy markets volatile, nuclear becomes essential for energy independence.”

Kong told POWER, “These facilities represent fully paid-for infrastructure with strong operational track records. Japan’s 80.5% capacity factor for restarted plants proves they can deliver always-on, clean electricity reliably. The challenge is ensuring they operate as efficiently and cost-effectively as possible while maintaining safety, and that’s where modern tools including AI can help optimize operations, streamline compliance, and reduce costs without compromising quality.”

|

|

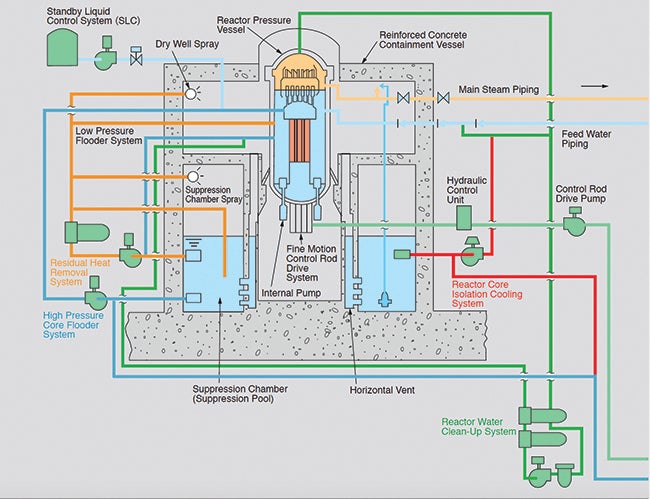

1. This is a graphic of the schematic design of an advanced boiling water reactor (ABWR). Hitachi said the ABWR’s features include a highly economical reactor core; reactor coolant recirculation system driven by internal pumps; advanced control rod drive mechanism; overall digital control and instrumentation; and a reinforced concrete containment vessel. Courtesy: Hitachi |

Hitachi was the main contractor for development of the reactor system for Unit 2 (Figure 1). The company also served as the main contractor, architect engineer, and reactor system supplier for Shimane Unit 1. Hitachi also has served as the main contractor for the development of Shimane Unit 3 prior to construction being halted. Hitachi-GE was the supplier for components for upgrading Unit 2, including the control rod drives, or CRDs, which required a significant time commitment for inspection and cleaning before the restart of the reactor.

The Japanese parliament in 2023 enacted a law to allow nuclear reactors in that country to operate beyond their current limit of 60 years, in order to help cut greenhouse gas emissions and ensure a sufficient energy supply. After the 2011 earthquake and tsunami, and subsequent incident at Fukushima, the country’s reliance on nuclear power was reduced from 25% of the power mix in 2010 to 1% in 2015, though it has since recovered to about 10%.

The public response, along with the regulatory climate, to nuclear power in Japan has been cautious after the Fukushima disaster, as Le Scornet noted. The Japanese government, though, in recent years has been more accepting of nuclear power, as the country wants to boost its energy security and reduce greenhouse gas emissions from its electricity sector.

The Cost of Safety Upgrades

Chugoku Electric, a few years ago at the beginning of the process to upgrade the plant for restart, had estimated that work to bolster safeguards would exceed 100 billion yen (about $656 million today). The safeguards included measures to protect the facility against seismic activity. The company later revised that figure upward to 600 billion yen, which today is about $4 billion.

Chugoku Electric, a few years ago at the beginning of the process to upgrade the plant for restart, had estimated that work to bolster safeguards would exceed 100 billion yen (about $656 million today). The safeguards included measures to protect the facility against seismic activity. The company later revised that figure upward to 600 billion yen, which today is about $4 billion.

The Shimane Unit 2 reactor passed a pre-restart inspection by Japan’s NRA in September 2021. After signoff from the cities of Matsue, Izumo, Yasugi, and Unnan, the governor of Shimane prefecture gave his approval in June 2022, paving the way for the restart. It would be more than two years before fuel was loaded into the core of Shimane 2, which officials said began on December 28 of last year. Chugoku officials said 560 fuel assemblies were loaded, a process completed in November of last year. The reactor began producing power in December of last year prior to resuming commercial operation the following month.

Chugoku President and CEO Kengo Nakagawa in a statement at that time said Shimane would “aim to be a power plant that provides peace of mind to the local community by striving to appropriately disclose information regarding the status and initiatives of the power plant, and providing detailed explanations at various opportunities.” Nakagawa added, “It is essential to support the stable supply of electricity, especially in the Chugoku region [in western Honshu, including Hiroshima], as well as to achieve carbon neutrality and stabilize electricity prices.”

Kingo Hayashi, chairman of the Federation of Electric Power Companies of Japan, in a statement said, “We believe this is the result of the various efforts that Chugoku Electric Power and its partner companies have made to make safety their number one priority, as well as the careful explanation of those efforts to the local community. We would like to express our gratitude and respect to Chugoku Electric Power, the local government where the plant is located, and all those involved in the project.”

“As the U.S. faces its own grid emergency with surging electricity demand from data centers and manufacturing, Japan’s experience offers critical lessons,” said Kong. “We have similar fully paid-for nuclear assets that just need to keep operating well and efficiently. Finding safe ways to maximize these facilities should be a national—and frankly, a national security priority.”

Kong added, “Japan’s nuclear restart program proves that countries can safely return to nuclear power after major incidents if they’re willing to invest in proper safety upgrades, build regulatory capability, and earn community trust through transparency. That’s the playbook for nuclear’s future globally.”

—Darrell Proctor is a senior editor for POWER.