Several factors favor natural gas when it comes to the future of U.S. power generation. But other forces, such as power demand, energy efficiency, and the impact of renewables, make it a complex fray.

Let’s talk about the obvious. Since 2008, coal-fired generation and coal production in the U.S. have been decimated. Next story.

Is the coal sector dead, merely biding its time before King Coal regains his throne, or left somewhere in purgatory? Well, it’s complicated.

A Brief History Lesson

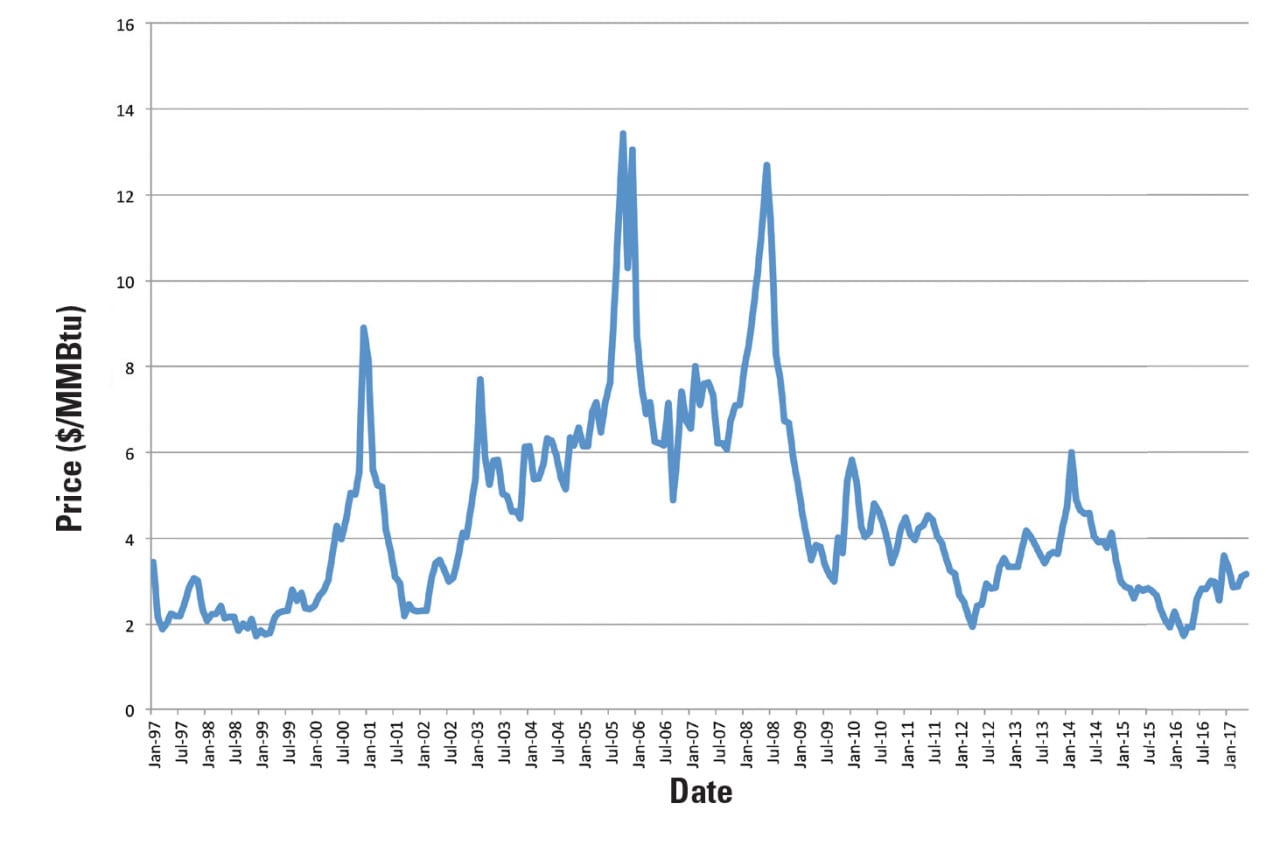

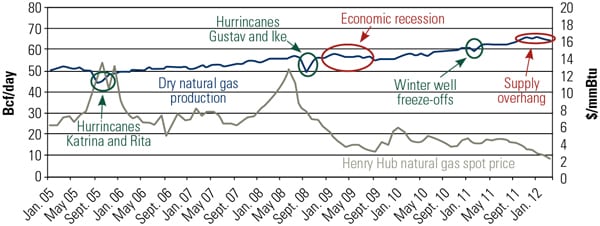

Since the beginning of the shale gas revolution in 2008, wholesale generation competition has favored natural gas-fired combined cycle facilities, resulting in reductions in coal-fired generation, coal production, and coal commodity prices.

Certainly, a portion of the reduction in coal consumption reflects the permanent closure of coal-fired plants. The combined pressure applied by low natural gas prices, environmental regulations, and normal maintenance costs of older coal-fired plants drove these closures—with low natural gas prices being the force driving many, if not most, of the retirements. Suffice it to say had natural gas prices been higher, some of these retiring coal-fired facilities would have limped along in lieu of retirement, albeit with lower operating margins.

However, these coal-fired retirements—a set of plants with relatively high fuel and operating costs—reflect only a small portion of the reduction in coal-fired demand witnessed in the U.S. For example, total 2015 coal-fired generation declined by approximately 555 TWh (or 30%) from 2008 levels. However, only about 185 TWh (or 30%) of this decline was due to retiring coal-fired facilities (Figure 1). In other words, even if all coal-fired retirements could be attributed to environmental control requirements (an aggressive assumption), the clear dominant factor attributable to the coal-fired generation decline is lower natural gas prices (at a minimum, approximately 70% of the decline).

In the wake of this reduction, the generation gap was filled primarily by existing and new natural gas-fired combined cycle facilities and renewable generation. Approximately two-thirds of the decline in coal-fired power output from 2008 to 2015 was shifted to natural gas-fired combined cycle facilities, with the remaining one-third shifted to renewable generation (primarily wind and solar).

How Close Is Close?

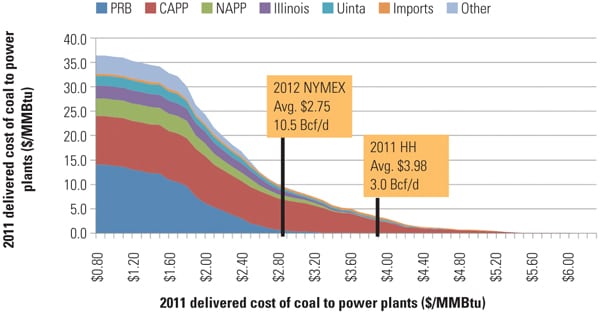

Coal- and natural gas-fired resources are continually competing against one another in day-ahead and real-time wholesale power markets. While unit operational constraints have some effect, these economic tradeoffs primarily distill down to relative fuel costs and operating efficiencies of these respective resources. So, holding relative operating efficiencies constant, as relative coal and natural gas fuel prices change, plant operations will shift.

At higher natural gas prices such as the $8+ per MMBtu average prices seen during 2008, coal-fired facilities were certainly always cheaper to operate as baseload resources relative to natural gas-fired combined cycle options. However, coal- and natural gas-fired resources are very competitive over a range of lower natural gas prices—for example, the $2 to $4 per MMBtu band (Figure 2) in which we currently find the market.

During 2016 the Henry Hub natural gas price averaged about $2.50/MMBtu, low enough that a natural gas-fired combined cycle unit would have been cheaper to operate than almost all U.S. coal-fired units. However, an increase in the delivered gas price of $0.75/MMBtu would make the natural gas-fired combined cycle plant costlier and reverse this short-term decision-making.

This relatively small band of potential natural gas price movement is important if we remember that the system has already “wrung out” less-efficient coal-fired resources due to combined regulatory and commodity pricing pressures. The remaining coal-fired fleet can operate at capacity factors of 70% and higher, as it did in 2008. However, as of 2015, the bulk of the U.S. coal-fired fleet was operating at about a 50% capacity factor. Therefore, assuming relatively small movements in natural gas commodity pricing, there is the potential for these plants to burn about 40% to 50% more coal than they did in 2015.

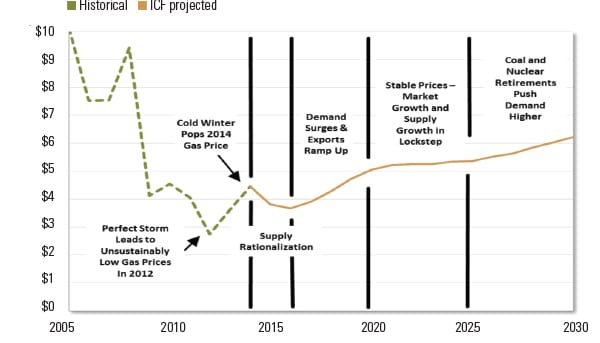

So, What Says the Crystal Ball?

As of May 31, 2017, the New York Merchantile Exchange Henry Hub forward curve sat at $3.03/MMBtu for calendar year 2018, with backwardation down to $2.86/MMBtu by 2021. Alternatively, our bottom-up fundamental view of Henry Hub pricing diverges from the forward curve after 2018, driving to approximately $3.85/MMBtu by 2021 on the back of increasing demand from Mexico, LNG export facilities, and the industrial and power sectors. Ultimately, there are a range of reasonable expectations that one can take by 2021 for natural gas price outcomes and, with it, implications for the coal sector.

The interactions among future market dynamics, including expanded coal retirements, coal and natural gas prices, increased renewable energy, energy efficiency, and myriad other market factors, are complex. PA Consulting Group’s analysis assumes current expectations of slow growth in power demand and continued additions of renewable generation capacity, and utilizes proprietary production cost and market modeling architecture. This modeling captures the effect of the differing regional mixes of generating capacity and operational constraints such as the need to keep some coal plants operating at all times.

Several key assumptions have driven PA’s analysis.

Incremental Coal-Fired Retirements. Since 2012, the U.S. has seen a swath of coal-fired power plant retirements, driven by a combination of low wholesale power prices, increased competition from natural gas-fired resources, and compliance with the Mercury and Air Toxics rule. Slightly more than 40 GW of coal retirements were completed between 2012 and mid-2016. Currently, an additional 10 GW of firm coal retirements are slated in the next five years.

Incremental Natural Gas-Fired Additions. Coal-to-gas switching is limited in regions without much installed gas capacity. In total, about 35 GW of new natural gas-fired combined cycle capacity is slated to come online between today and 2020, with the bulk planned for regions where there is a large amount of installed coal-fired capacity.

Natural Gas Price Scenarios. PA analyzed three alternative cases with Henry Hub prices set at a nominal price of $2.50/MMBtu (the “Low-Gas Case”), $3.00/MMBtu (the “Mid-Gas Case”) and $4.00/MMBtu (the “High-Gas Case”). These cases were compared to a base price of 2017 Henry Hub gas at $3.25/MMBtu.

Coal Prices. For PA’s analysis, delivered coal prices were held constant under each natural gas price scenario, with prices comprised of a commodity price and a transportation charge developed by Hellerworx. The forecast reflects recent upward movements in coal pricing for 2017, as coal prices have already shown some near-term recovery from the lows of spring 2016.

In each case, all model inputs were identical except for differing natural gas prices, in order to evaluate the independent impact on power prices and power-sector coal demand, and incremental coal demand was calculated as total coal burn in each basin under the respective gas case, less the coal demand for that basin from the base for 2017.

As expected, the analysis shows substantial sensitivity of power sector coal demand to natural gas price swings. In summary, coal demand is severely injured when natural gas price levels fall below $3.00/MMBtu. Conversely, at natural gas price breakpoints above $3.50/MMBtu, coal volumes increase substantially. This tight band of prices is smaller than the recent market range. For example, monthly prices in 2016 fluctuated from $1.73/MMBtu to $3.59/MMBtu at Henry Hub.

PA’s analysis of the various price case scenarios resulted in a wide range of coal usage totals.

Low-Gas Case ($2.50/MMBtu). At these natural gas prices (approximately $0.75/MMBtu below 2017 base natural gas pricing), coal volumes across all basins drop by 185 million tons compared to 2017 base levels, or 21% of 2015 production. Powder River Basin (PRB) coal exhibited the largest decline, absorbing 99 million tons of lost tonnage or 24% of 2015 production, while the Appalachian and Illinois basins could see volume declines reaching 14% to 17% of 2015 production. Gas demand would increase by 7.0 billion cubic feet (Bcf) per day.

Mid-Gas Case ($3.00/MMBtu). At these natural gas prices (approximately $0.25/MMBtu below 2017 base natural gas pricing), coal volumes across all basins drop 69 million tons compared to 2017 base levels, or 8% of 2015 coal production. PRB coal would again see the largest decline, losing 38 million tons or 9% of 2015 production, while the Appalachian and Illinois basins could see volume losses comprising 5% to 7% of 2015 volumes. Gas demand would increase by 2.6 Bcf/day.

High-Gas Case ($4.00/MMBtu). At these natural gas prices (approximately $0.75/MMBtu above 2017 base natural gas pricing), coal volumes would increase approximately 129 million tons compared to 2017 base levels. PRB coal would again comprise the lion’s share of swing volumes, with an incremental 68 million tons of demand. Central and Northern Appalachian basins could also see a combined incremental 27 million tons of coal burn as a number of Mid-Atlantic coal units become competitive versus regional gas plants.

Two clear conclusions emerged:

■ Swing coal production potential is big. At current coal price levels, PA’s results reflect a possible maximum swing of 315 million tons of power sector coal burn across the full range of natural gas prices examined.

■ Peak coal is in the past. Even under the High-Gas Case, total U.S. coal consumption would top out at approximately 790 million tons, compared to 1,046 million tons in 2008 (peak historical levels). Even if closed coal-fired facilities could be unretired, those higher-cost facilities would burn much less than the 100 million tons they consumed in 2008 given lower expected natural gas prices in today’s environment. Over this period, the effect of Trump-era loosening of Environmental Protection Agency regulations will be negligible, and incremental natural gas-fired combined cycle additions through 2020 will further constrain any potential growth.

What Role Will the Railroads Play?

The railroad response to the severe decline in coal production and consumption during the 2008–2016 period has been surprising and instructive. Because the railroads often have very limited competition and much higher margins than coal producers, they have more ability, but less market pressure, to reduce margins than do coal producers. There are four major railroads that originate U.S. coal: Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) and Union Pacific (UP) in the West, and CSX Transportation (CSX) and Norfolk Southern (NS) in the East and Midwest. Shortlines and other Class I’s handle U.S. coals as well, but these four are the primary carriers.

While coal prices from the PRB declined substantially during this time period, the railroad response was minimal. BNSF was more responsive than UP, including offering some spot pricing into Texas that was tied to gas prices, but rail rates stayed largely static, and it is unclear how much additional volume the more aggressive BNSF rates generated. The railroads chose to accept major declines in coal tonnage shipped rather than make major reductions in rates.

The effects were similar in the East. Neither CSX nor NS seems to have attempted to compete with natural gas-fired generation on a large scale anywhere in the eastern U.S. Both CSX and NS instead appeared to have accepted large losses in coal volume (totaling about 50% between 2008 and 2016, including a 25% decline during the past two years alone) rather than making major reductions in rail rates. While the carriers probably could not have reduced rates sufficiently to avoid some losses of coal volume to cheap natural gas, their failure to respond seemed to indicate a desire to maintain their rate structures in the belief that when gas prices strengthened, they would be able to achieve higher revenues on the remaining reduced volume levels. CSX did implement a fixed and variable pricing structure to induce generators to dispatch on the lower variable cost component while making up the difference in a fixed charge with no net rate reduction. However, the development of contracts with rail rates that are truly gas price sensitive is a work in progress.

Looking Ahead

Put together, the reduction in coal-fired power generation with falling gas prices indicates that the fall in coal prices was not enough to restore the competitive position of coal. For most power plants in areas outside the Ohio River Valley, rail transportation costs are a large portion of delivered prices and, as illustrated, the railroads mostly chose not to reduce prices as natural gas prices fell and coal consumption dropped, preferring a higher margin on lower tonnage.

In contrast to the rail industry, which failed to reduce rates significantly in response to competition from natural gas-fired generators, coal commodity prices and volumes declined so sharply that bankruptcies and mine closures became pervasive. Since April 2015, huge portions of the U.S. coal industry, including some of the largest publicly traded companies, have experienced bankruptcy.

Operators that did not go bankrupt have closed many mining operations. In addition, many smaller operations ceased production or have gone out of business. The net effect is a U.S. coal production sector with significantly less capacity than it had three years ago, and likely less ability to rapidly respond to market demand fluctuations. Greater price volatility is possible as a result.

Clearly, an increase in natural gas prices from the recent range of $2.00/MMBtu to $3.00/MMBtu, to $4.00/MMBtu would produce a substantial increase in coal burned for power generation. However, at the moment, the forward curve for gas prices is not high enough to permit much increase in coal consumption or prices.

Coal producers are mostly price-takers without much flexibility to influence the market. From their point of view, the opportunity and the danger is the volatility of gas prices. Given the limited surplus capacity in the coal industry, it would not take much increase in coal burn to spike coal prices. If that happens, will producers try to capture the spike or opt for longer-term contracts at somewhat lower prices? And, what then will be the reaction among coal-fired owners regarding the long-term viability of their fleet?

Railroads have more choice about pricing and potentially a substantial influence on the competitiveness of coal versus natural gas. To use their pricing flexibility, railroads must consider the complexity of coal versus natural gas competition in power markets. They must be sensitive to the preservation of a coal transportation pricing structure that has some limited elements of rail-to-rail competition. They are grappling with these questions now.

PA’s analysis shows that the uncertainty facing all parties is remarkably large, given the plausible range of gas prices. In the lower end of that range, the Kingdom of Coal will be a modest and shrinking one. At the higher end, coal producers and railroads could experience a sustainable business. ■

—Mark Repsher is an energy expert at PA Consulting Group; Jamie Heller is founder and president of Hellerworx; Trygve Gaalaas is president of Hawk Consulting Services; and Charlie Mann is director at Energy Investors Advisors.