In early 2020, the prevailing narrative in the power sector was a continuation story of the developments from the decade before: renewable buildout will keep compounding, thermal capacity will keep retiring (albeit at a slower rate), markets will evolve to compensate for flexible generation products, capital will keep moving earlier in the development value chain and the grid will gradually transition to a cleaner fuel mix.

But soon enough, this “straight-line” version of that story started losing strength. COVID-era supply chain disruptions and the start of the U.S.-China economic decoupling across strategic industries exposed how fragile “just-in-time” global energy supply chains really were. Interest rates reset the cost of capital, changing what penciled out and what didn’t. Project development has become a riskier proposition. Reliability concerns around dispatchability and extreme events moved from theoretical to visible. The energy transition didn’t fizzle out but instead slowed down and stopped being linear.

COMMENTARY

As we reach year-end 2025, the narrative of the U.S. power sector has shifted drastically. Power is no longer just one chapter of the energy transition; it has become a strategic constraint on nationwide economic growth. Artificial intelligence (AI)-driven data center loads are now arriving fast and in clusters and require strict reliability. In that sense, this new race for “power for compute” resembles prior historic industrial and infrastructure turning points (e.g., the 19th century buildout of railroads, early 20th century mass electrification, the telecom network rollout) rather than the prior decade’s slow incremental load growth and thermal generation attrition. And because leadership in AI has significant geopolitical consequences, the electricity abundance needed to catalyze the new data center economy is now part of the great power competition between the U.S. and China.

Data centers represent a once-in-a-century demand shock. Demand growth from U.S. data centers is hard to fathom. Data centers are expected to represent up to 12% of total U.S. electricity consumption by 2028 (up from ~4.4% in 2023). They are the key driver for forecasted 5.7% annual energy demand growth in the U.S. over the next five years (compared to a sluggish 0.2% annual average in the 2010s).

The challenge is not just the absolute scale of growth, but the speed of incremental demand additions; each new data center can be akin to adding a large city’s electricity demand to the grid, often within just one to two years. This puts enormous pressure on power infrastructure. This pressure is often local before it is national: Pew Research notes extreme regional concentration already (e.g., data centers consuming more than 25% of Virginia’s electricity in recent years).

This is why the AI load wave may feel like a national story but behaves operationally like a regional story. It shows up as a reliability and deliverability problem in specific places where power, fiber, land, incentives and workforce overlap. This is often not where interconnection is easiest.

PEI expects that as premium locations are exhausted, data center demand will start moving to the next best alternative locations and will become more geographically spread in the mid-term. Tier II markets such as Austin-San Antonio in Texas, and Las Vegas-Reno in Nevada, are already displaying increased momentum, as well as rural locations like Louisiana and North Dakota.

This is a “once-in-a-century” industrial demand shock: AI and data center growth is reshaping energy infrastructure in ways comparable to prior waves of large-scale infrastructure expansion and geostrategic races. Electricity is at the core of compute competitiveness because large-scale AI requires highly reliable baseload-like supply.

The AI race turns electrons into a strategic input. AI’s role in demand means that the power sector is once again a national priority. As compute depends on electricity, U.S. AI competitiveness hinges on reliable electricity infrastructure to support data centers. Moreover, supply chains are no longer “just economics.” U.S. policy and trade enforcement have increasingly constrained reliance on certain China-linked energy inputs.

The Department of Energy’s “Speed to Power” initiative is framed as a federal effort to accelerate large- scale generation and transmission development “to win the AI race.” This is a direct signal that electricity abundance is now being treated as a matter of global economic competitiveness and national security interest. This laser-focused federal action echoes the same catalysts behind prior large scale industrial buildout efforts in the U.S., supplementing private capital with strong policy directions and financial support.

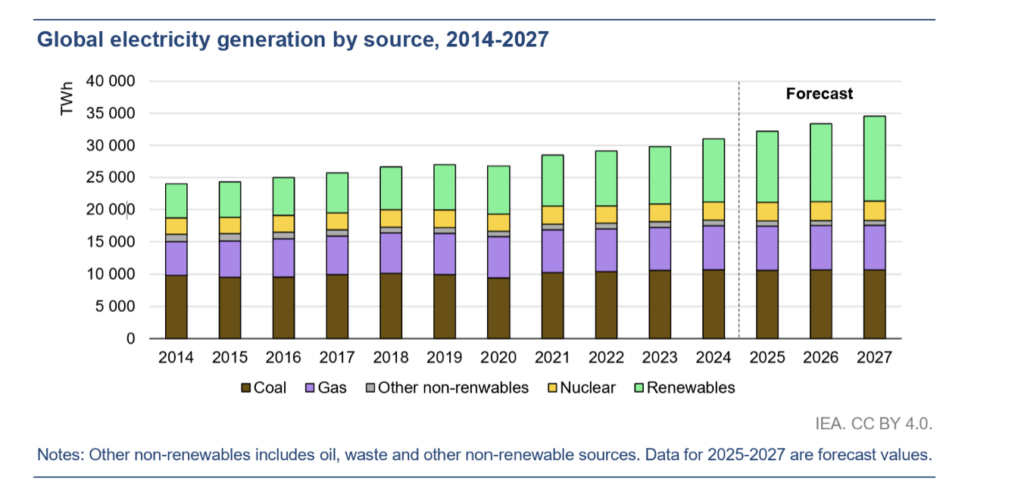

Global context matters as well. In 2024, China built more than 50 GW of thermal generation and 277 GW of utility-scale solar, according to government figures, versus the U.S. at ~2.5 GW thermal generation and ~40 GW solar, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). It is a sobering reminder that the ability to build power plants is itself a competitive advantage. This also demonstrates why, in the U.S., solar and storage will continue to be built out to the maximum feasible system capacity alongside thermal capacity—not because they solve reliability alone, but because they are among the fastest scalable sources of incremental energy in a build-constrained environment.

If the power sector falls behind expectations of policymakers (i.e., if capacity deployment timelines remain incompatible with strategic AI load and reliability needs), federal support could plausibly increase accordingly. This could take many forms: expedited siting/permitting for large-scale resources, new approaches to transmission corridors and cost allocation or federal coordination around “national priority” projects.

From cheap MWh to deliverable firm power: how AI demand is repricing reliability. Rapid improvements in wind and solar technology; supported by state and federal incentives drove a surge in intermittent generation, with solar levelized cost of energy (LCOE) falling by roughly 85% between 2010 and 2019. Grid operators were able to integrate this capacity largely because many markets still had significant thermal oversupply and anemic demand growth, allowing renewable growth and plant retirements to occur without immediate reliability pressures. Two key structural changes collided to shift the narrative:

1) Demand is back, and it is concentrated. Data center and AI loads are large and often need to locate near power, fiber networks, metro areas and talent. This demand is less sensitive to power prices as long as reliability needs are met. The result is localized scarcity: at certain nodes, the system doesn’t need more “clean annual MWh” as much as it needs more deliverable capacity.

2) There is scarcity of available firm power. Offtakers increasingly want firmness, not just energy attributes. They want firm service (based on location, shape of load and availability) because downtime and curtailment risk are existential to large AI workloads (resulting in the industry- standard 99.999% uptime requirement). This does not mean that offtakers are walking away from their prior environmental commitments, but rather that their key priority has shifted pragmatically towards reliability. Of course, if reliability is assured, hyperscalers still prefer clean solutions.

These factors are creating a market dominated by two main themes: At a national level, renewables continue to add needed lowest-cost marginal energy to the system; and, constrained grids create a premium for firm, deliverable power, where pricing reflects the scarcity of capacity that can show up when and where it is needed.

In other words, there has been an investment logic shift away from just a “cheap energy” ideal (where the goal is to produce MWhs at the lowest LCOE) to a “deliverability + firmness” ideal (where the goal is to provide assured service with MWhs delivered with high probability, plus the capacity attributes that keep the system stable). In this world, firmness is repriced, and the market is creating “reliability as a product.”

One of the clearest signals of this regime change is the widening gap between what consensus market forward price curves imply for energy, and what large-load buyers are willing to pay for firm, long-dated, deliverable supply.

One telling example is Vistra’s recent announcement of a 20-year power purchase agreement (PPA) with a large investment-grade counterparty for up to 1,200 MW of its Texas-based Comanche Peak nuclear plant. The implied PPA pricing was ~$90–$100/MWh, with PEI analysis backing into an implied reliability/capacity value of roughly

~$24/kW-month (~$790/MW-day). This is a clear expression of how valuable reliable capacity has become in ERCOT.

The Comanche Peak deal suggests that forward forecasts and markets may not fully capture the gravity of inadequate reliable supply over the long run. This is what firm clean power looks like when it moves from aspiration to contracting reality, driven by price insensitive large-scale demand from data centers.

The new power sector bottleneck is not capital, but execution: interconnection, equipment, and build-out rate. There is roughly ~2 TW of utility-scale solar and BESS projects in U.S. interconnection queues, according to published information. The U.S. built roughly ~40 GW utility-scale solar and ~10 GW utility-scale BESS in 2024, implying only ~2% of queued capacity gets built annually, according to EIA. The agency’s expectations for 2025 additions (~33 GW solar, ~18 GW storage) underline the same low throughput, which indicates structural constraints that are not related to project pipelines or capital.

Equipment lead times for projects are now a key input in strategy, not just a procurement detail. Transformers are emblematic of this deep shift. Lead times for generation step-up transformers have been documented at ~143 weeks in 2025, and large transformer lead times are widely reported as stretching into multi-year territory.

These dynamics suggest that next decade’s winners will not only be those with low cost of capital. Winners will be those with streamlined execution platforms who can seamlessly manage and integrate land, permits, queue position, contracting and construction resources, with the capacity and know-how to build generation where and when needed by data centers.

What the next decade will look like for the U.S. power sector. Near-term (2026–2030): “Speed to power” is the name of the game. When capacity demand timelines compress, the system reaches for what can be delivered most rapidly, regardless of technology type:

- Continued deployment of solar and BESS, given their fast speed to market and significantly shorter development timelines.

- Utilizing existing generation more efficiently (uprates, extending run time, improving availability).

- Leveraging existing interconnections.

- Repowering and life-extending where feasible (including nuclear where permitted).

- Self-build / behind-the-meter solutions where grid timelines are too slow.

- Adding dispatchable generation where policy and permitting allow.

This is also where scarcity emerges in unexpected places: access to turbine kits, interconnection equipment, transformers, EPC capacity and viable sites becomes a scarce commodity.

Mid-term (2030–2035): The bulk of incremental firm supply is likely to consist of combined cycles

(plus select peakers), but at a higher cost ceiling. As demand growth persists and interconnection/transmission reform remains slow, the system’s mid- cycle “workhorse” is likely to be combined-cycle gas turbine (CCGT) new builds, supplemented by peakers and uprates, because these remain the most scalable dispatchable mid-term option that can be replicated across many regions.

However, the economics no longer resemble the “cheap gas build” era of the 2010s. Capital costs for new combined-cycle projects have increased materially as turbine supply tightens, EPC bandwidth remains constrained, and labor markets stay competitive. Industry leaders have noted that all-in CCGT costs, which were roughly ~$1,200/kW in 2022, can now approach ~$2,500–$2,800/kW, according to NextEra investor relations, depending on configuration and site conditions.

Despite these higher costs, new CCGTs are becoming essential infrastructure for supporting large-scale data-center expansion. Many of these projects are likely to be developed under long-term, 20-year offtake arrangements that explicitly value deliverability, availability and speed-to-power.

Higher capital requirements naturally imply upward pressure on electricity prices, but it is uncertain how much of this cost increase regulators will permit to be fully socialized; especially as a meaningful share of incremental demand originates from a single high-growth industry. This tension between system-wide reliability needs and ratepayer protection will shape procurement and cost-allocation debates across several regions.

As a result, we expect increasing interest in microgrid and behind-the-meter solutions, particularly for large data center operators and industrial loads seeking to insulate themselves from regulatory uncertainty, interconnection delays and the rising cost of grid-supplied electricity. These alternative architectures may become an important release valve as policy makers balance affordability, fairness and the need to bring firm capacity online quickly.

Ultimately, the rising capex environment reinforces why near-term reliability additions continue to favor existing interconnections, uprates and brownfield advantages: these are pathways that compress both cost and schedule risk while the system races to meet rapidly clustering load.

Post-2035: New firm clean generation technologies could become meaningfully additive (SMRs and geothermal), but the timeline remains uncertain. Geothermal and SMRs can plausibly become real contributors after 2035, because they provide a dual solution for AI load: firm, carbon-free power with high availability. The critical question is not concept but buildability (repeatability, standardization and supply chain, as well as cost).

Capital support is clearly building for both technologies. Amazon has publicly signed agreements to support SMR development (including projects expected in the early 2030s) and invested in X-energy; broader private capital and public support are also accelerating the space.

On the federal side, the DOE recently announced up to $800 million of support for SMR projects (given to TVA and Holtec), explicitly linked to rising demand from AI and other loads.

For geothermal, next-generation developers have raised substantial capital to scale enhanced geothermal projects aimed at bringing firm capacity online before the decade ends, laying the groundwork for larger contributions in the following decade.

Power sector implications: the investment playbook evolves. The AI/data center cycle reshapes the opportunity set. It pulls forward new builds, but it also re-values operating assets. In a system where “getting built” is the binding constraint, operating assets with proven interconnection, permits, fuel access and deliverability increasingly behave like scarce inventory. The recent Three Mile Island nuclear plant revival is a clear indication of today’s need for near-term power.

Existing thermal assets remain scarce and mergers and acquisitions (M&A) are active into 2026 (with non-CCGT moving to center stage). For much of the last two decades, thermal generation was underwritten as an attrition story. That is no longer valid. Regardless of technology or fuel, there is renewed demand for dispatchable generation, driven primarily by public IPPs; regulated utilities; and sponsor-backed scaled platforms. While assets in the highest-growth areas are trading at significant premiums, the valuation uplift is increasingly broad-based across the sector.

A key accelerant is the private-to-public arbitrage: many private transactions are clearing around ~6–9x EV/EBITDA, while public IPPs trade >11x, creating room for accretive consolidation. We expect this M&A cycle to continue in 2026, with non-CCGT assets (older-vintage gas, peakers and coal) taking a larger share of processes as buyers prioritize near-term deliverability and time-to-power.

In this environment, PEI is seeing these dynamics play out in real time across the M&A landscape. Processes are increasingly shaped by buyers who value deliverability, contractability and speed, and we are advising on a growing number of both buy-side and sell-side mandates where these themes are central. Market tension is rising as competitive investors, public IPPs, utilities, infrastructure funds and global strategics pursue scarce operating thermal assets, and we are leveraging our market insights to help clients frame and capture that value.

Parallel financing activity has also become a defining feature of current processes: we are routinely running sell-side financing processes alongside M&A to establish valuation floors, sharpen valuation benchmarks and broaden the field of premium buyers. Across these live mandates, PEI’s combination of investor access, power-market expertise, specialist debt advisory and proprietary analytics is proving critical in positioning assets for maximum resonance with the market and delivering superior outcomes for clients.

Thermal development is fashionable again and “speed-to-power” is the premium attribute. Thermal development is back in the investable set, supported by favorable contract terms and strong demand for shovel-ready, fully permitted projects. In this environment, the market is increasingly indifferent to technology labels and intensely sensitive to schedule. Projects that can credibly reach operations quickly (not just projects with attractive long-run economics) command a premium.

That premium is even higher for developers who have secured equipment ahead of construction financing. Original equipment manufacturers (OEM) are increasingly asking for earlier payments to lock turbine slots, and the ability to de-risk equipment has become a core value-creation lever.

PEI is observing this dynamic firsthand in the market. We are raising debt and equity for thermal development across markets and have been supporting developers with equipment and pre-construction financing solutions that de-risk procurement and compress timeline risk, often translating directly into better contractability and higher valuations.

U.S. renewables continue to attract global capital. There is still deep global interest in U.S. renewables, but it is increasingly focused on large platforms with operating portfolios and credible pipelines. Global investors (including pension funds, sovereign wealth funds and other large institutions) are looking to write large checks for scalable opportunities that provide capacity deployment certainty and repeatability. This sets up a more active sell-down environment in 2026.

While single asset or small portfolio transactions can be more challenging, there are strategic paths that can be pursued, including sell-downs and structured equity solutions, that provide floor valuations and create competitive tensions for maximizing transaction outcomes.

PEI is the leading specialist investment bank in designing and running global M&A processes and bringing global investors into U.S. opportunities. PEI’s Hong Kong presence supports that outreach with boots-on-the-ground coverage of cross-border investors pursuing U.S. renewables platforms.

Creative financing becomes a competitive advantage for renewable platforms (LCs + private credit + flexibility). As pipelines grow, LC and deposit requirements rise and development timelines extend, renewable platforms are increasingly turning to bank-financed pre-NTP LC facilities to keep projects moving through queues and procurement milestones. These facilities are becoming larger and more strategic as platforms scale. In parallel, more developers are using private credit and structured equity solutions for construction equity needs. Such options are often non-dilutive and more cost competitive compared to traditional equity, allowing platforms to recycle capital and grow faster.

In short, creative financing solutions are now a structural part of the renewable ecosystem. Platforms that adopt them early will be one step ahead. PEI is actively structuring these solutions, designing tailored LC facilities, junior capital solutions and working across bank and private-credit markets to deliver flexible, developer-specific capital that supports growth and aligns with the new reality of longer timelines and higher collateral intensity.

The U.S. power sector has entered a defining decade shaped by speed, reliability and electricity pragmatism. The slow-and-steady transition narrative of the last cycle has collided with today’s data center driven load growth and unexpected shifts in supply chains, cost of capital and system reliability. The coming years will require balancing these pressures while supporting U.S. economic competitiveness and geopolitical strength, with federal policy once again serving as an essential backdrop. In this environment, the most valuable power will not be the cheapest MWh but the power that is deliverable, firm, financeable and on time.

—Adil Sener is partner at PEI Global Partners LLC. This material has been prepared by PEI Global Partners Holdings LLC and PEI Global Partners LLC (together, “PEI”) a U.S.-registered broker-dealer. This communication is being provided strictly for informational purposes only. Any views or opinions expressed herein are solely those of the institutions identified, not PEI.

- coal plant retirements

- electricity reliability

- Federal Power Act

- emergency orders

- baseload generation

- coal-fired power plants

- reliability must run

- power plant closures

- DOE

- Section 202(c)

- federal intervention

- utilities

- ratepayer costs

- grid reliability

- WECC

- energy policy

- MISO

- electric cooperatives

- resource adequacy

- power markets