From Ancient Chariots to Modern Turbines—A History of Lubricants

Lubricants have been around for thousands of years, serving a multitude of purposes. The technology has come a long way since olive oil was used to move stones and other heavy objects as far back as the 17th century B.C., according to archaeological discoveries. Petroleum-based products helped usher in the industrial age, and advancements in refining and production techniques continue the historical arc.

POWER

Lubricants for industrial systems have evolved over time, though their basic purpose—to improve the performance, and prolong the lifecycle, of machines—has not changed over the years. In a world increasingly dependent on those machines, materials that lubricate moving parts are essential to everyday life.

A lubricant is defined as any substance placed between surfaces to decrease friction and wear, though lubricants today also act as electrical insulators, coolants, cleaning agents, and even rust preventatives. Lubrication systems date at least to ancient Egypt, when olive oil was used to help move large objects. Lubricants, mostly made from animal fats and vegetable oils, were used on the axles of chariots and other transport vehicles for centuries.

Examples of early chariots were found in tombs of Egyptian nobles that date to 1,400 B.C. It’s said that the Egyptians realized the wheels of their chariots were being charred by heat created by friction. Using olive oils and fats not only dissipated heat; the lubricants prevented its creation in the first place. The wheels also turned more freely, and machine lubrication was born.

In the 8th century B.C., the Chinese developed a friction-reducing mixture of vegetable oils. Plenty of advancements took place in the intervening centuries, with scientific studies of friction and the movement of objects. From an industrial perspective, a major step forward occurred after the first oil well was drilled in Titusville, Pennsylvania, in 1859. The advent of the petroleum age brought forth a new economy based on oil, natural gas, and refined products from petroleum. Several companies entered the business to serve the growing need for lubricants across various industries.

The first U.S. commercial power plant—the coal-fired Pearl Street Station in New York City—entered service in 1882, the same year POWER was first published. The power generation industry presented a major opportunity for lubricant manufacturers, much as the auto industry did a few decades later.

Among the companies created to serve the ever-growing need for industrial lubricants was the Phillips Petroleum Co., founded in 1917 in Bartlesville, Oklahoma. The company specialized in extracting liquids from natural gas; by 1925, Phillips was the largest U.S. producer of natural gas liquids.

“Industrial lubrication has been used since the time of the Egyptians,” said Steve Plopper, product engineer at Phillips 66. “It wasn’t until the industrial revolution of the 19th century that there were major advances in formulations. Phillips 66 has been refining since acquiring our first refinery in 1927 and we continue to produce quality fuel and finished lubricants to this day.”

Phillips 66 for years was part of ConocoPhillips. It became a standalone company a decade ago, spinning off from its parent.

Built on more than 130 years of experience, Phillips 66 is a growing energy manufacturing and logistics company. Its diverse portfolio has vast opportunities in a changing energy landscape.

Phillips 66 Lubricants reaches across every key lubricants market, including automotive, trucking, agriculture, aviation, power generation, mining, and construction. Known for high-quality base oils and sophisticated formulations, Phillips 66 Lubricants also operates proprietary research and development facilities, as well as a comprehensive global distribution network.

Today the company is involved in several fields across a range of technologies, including solid oxide fuel cells, organic photovoltaics, and batteries in addition to lubricants and its signature fuels stations.

According to the Phillips Petroleum Company Museum in Bartlesville, the “Phillips 66” name came about by a combination of events. The specific gravity of the gasoline was close to 66; the car being used to test the fuel traveled at 66 miles per hour; and the test took place on U.S. Route 66, one of the original highways in the U.S. Numbered Highway System. It’s easy to see why a company naming committee unanimously voted for “Phillips 66” … and as the phrase goes, “the rest is history.”

Industry Provides Boost for Lubricants

Growth in the power generation industry in many ways has paralleled that of the automotive industry, and the evolution of today’s lubrication technology got a jumpstart in the 1920s as the auto industry began to boom. Lubricant manufacturers diligently worked to improve their petroleum based lubrication systems to improve the performance of engines and other machines. Varied treatment processes were developed, including solvent refining.

The 1930s saw the introduction of additives, which helped protect against corrosion. Pour points—the lowest temperature at which a lubricant will flow in liquid form—were enhanced, and viscosity—how resistant a lubricant is to flow—was improved. As engine and machine performance became more efficient, and the service life was extended, the benefit of lubricants became more obvious, and the product began to be used more widely. And the need for new formulations continued alongside the ongoing enhancements to the machinery.

“The advancement of industrial lubricants has come a long way, and Phillips 66 has been at the forefront with our excellent research and development team at the Phillips 66 Research Center in Bartlesville, Oklahoma,” said Plopper. “As technology has advanced, so too have the power generation lubricants such as our new Diamond Class Turbine Oils (Figure 1). The demands of new technology have required lubricants to improve and perform better.”

Rapid Advancement

Lubrication technology has advanced rapidly in the past century, as Plopper noted, and contributed mightily to advancing industry and economic development. Industrial lubrication systems benefited the functionality of metalworking equipment and machines.

Hydro-processing technologies, developed in the 1970s, brought major improvements in oil purification and performance, and lubrication systems have continued to advance in concert with more advanced machinery. That’s been true across many industries and certainly in the power generation sector, as turbine and boiler technology has evolved with a focus on improved efficiency and longer equipment lifecycles.

Lubricants in the power generation sector, as in every industry, are important because they are the lifeblood of the equipment utilized to produce the goods and services that we use every day. Lubricants allow machinery to operate and perform their duties to provide energy and overall better quality of life.

Decades of Evolution

To get a better understanding of where lubricant manufacturing stands today, it’s important to know how companies such as Phillips 66 supported the industry’s evolution, in what could be characterized as a century of innovation for the sector. That evolution continues, as lubrication systems are continuously being improved as more and more advanced machinery for a variety of industries is developed.

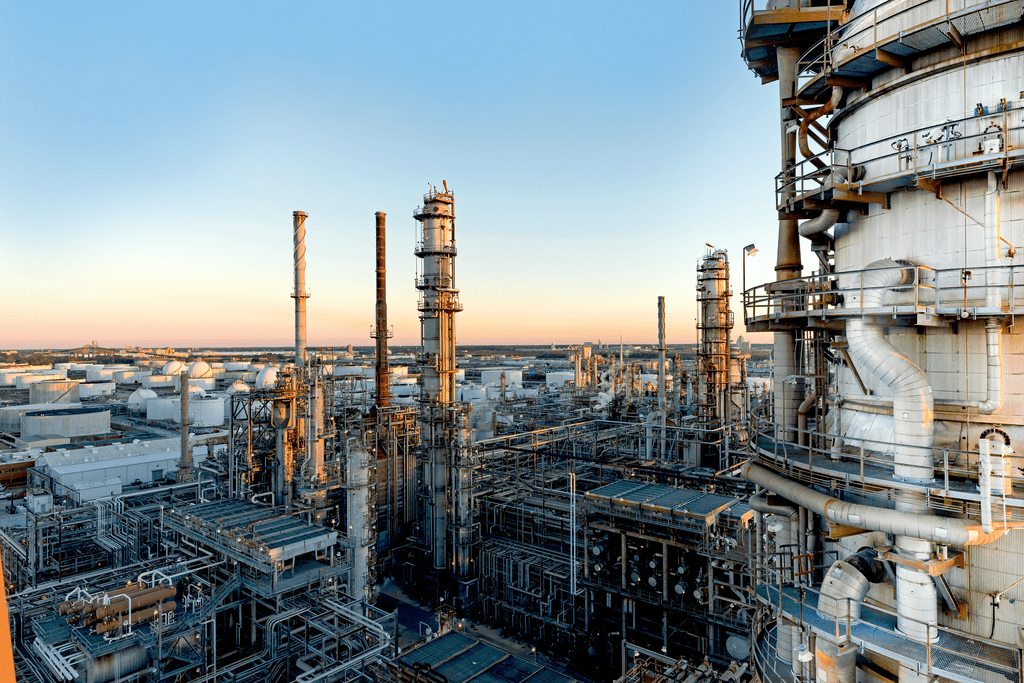

Much of the work is done in concert with refining operations. Phillips 66 operates refineries (Figure 2) in several locations, from California to Texas to the Louisiana Gulf Coast, and even New Jersey. The company offers nearly four dozen lubrication products for the power generation sector.

As the decades have rolled by, there has been a constant for all those years—industrial lubricants are always being produced, with the goal of better productivity, performance, efficiency, and sustainability. An article published by the Cambridge University Press notes that “Primitive man probably noticed how much easier it was to haul logs that had been stripped of bark because of the lubrication provided by sap oozing from the wood. Other prehistoric lubricants were mud or crushed reeds placed under dragged sledges for hauling game or timbers and rocks for building construction.”

The article notes, “More extensive use of lubrication was required with the invention of the wheel and axle. The first carts were made with crude wooden axles and bearings. Eventually, people discovered that smearing a lump of animal fat on the dry and squeaking parts made the wheel run quietly and smoothly. However, without the scientific concept of friction, no one knew why.”

Science would eventually provide the answer, thanks to the work of scholars such as Osborne Reynolds, Frank Philip Bowden, and David Tabor, among others. Reynolds was a pioneer in the understanding of fluid dynamics. In 1886, he derived the Reynolds Equation, a partial differential equation governing the pressure distribution of thin viscous fluid films in lubrication theory. In 1950, physicists Bowden and Tabor wrote the book The Friction and Lubrication of Solids. The book was considered by many experts to be a landmark in the development of the subject of tribology.

An early reference to crude oil being used as a lubricant is from writings about a cotton spinning mill in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in 1845. Historians have said the mill’s owner used mineral oil, obtained from a salt well drilled on the Allegheny River, and mixed it with the sperm oil that had been used to lubricate the mill’s spindles. The mixture worked better than just the sperm oil alone. And when the first actual oil well was drilled in Pennsylvania a few years later, it opened the door to petroleum-based lubricants.

Power Generation

Phillips 66 Lubricants notes all segments of the power generation industry depend on lubricants, be it a thermal or renewable energy installation. All manner of turbines and engines need lubrication, whether it’s a spinning wind turbine, gas-powered engine, boiler feed pump, or equipment at a hydropower plant.

The formulation requirements of lubricants differ among industries, a reason why careful selection of the right additives is so important to lubricant production. The additives in lubricants are different depending on types of oils and the requirements of the equipment. Demulsibility [sometimes expressed as the rate at which a liquid, such as an oil, separates from an emulsion], anti-wear, shear rates, and viscosity indices are all examples of different characteristics that these oils may or may not possess. The application dictates what each lubricant must include for the protection of the vital components. According to experts at Phillips 66 Lubricants, automotive lubricants have some of the same characteristics that power generation lubricants have, but may also be vastly different based on the operation and protection needed.

Formulating the right lubricant for a specific type of equipment has been core to the evolution of the industry. Different applications require unique approaches for lubrications. System setup, fluid chemistry, and operating conditions are just some of the factors that necessitate the host of unique formulations options that Phillips 66 Lubricants provides.

Turbine Oils

Turbine oils are key for the power generation industry, and often are said to be relatively simple, with a mixture of base oil, corrosion inhibitors, oxidation inhibitors, defoamants, and demulsifiers. But there’s more to it when it comes to finding the right formulation.

To design a premium-quality turbine oil that meets modern requirements, Phillips 66 engineers use optimal base oils, antioxidants, rust inhibitors, and other additives, which interact favorably to improve oxidation resistance, sludge and varnish control, and water separation. Their latest oils also offer improved Rotating Pressure Vessel Oxidation Test (RPVOT) retention, rust and corrosion reduction, and foam and entrained air release. The effectiveness of the Phillips 66 Diamond Class turbine oil was confirmed by dry turbine oil oxidation stability test (TOST) data.

RPVOT is a procedure that determines the oxidation stability of an oil. It measures the actual resistance to oil oxidation, whereas other tests detect oxidation that is already present in the oil. Oil oxidation is considered an “undesirable” series of chemical reactions involving oxygen that degrades the quality of an oil.

Next-generation power turbines are tasked with operating under severe conditions marked by increased flow rates, high energy output, and high operating temperatures. These design and operating parameters require more from turbine oils in terms of protection against oxidation, sludge, and varnish formation. Phillips 66 Lubricants has effectively re-engineered turbine oils to meet such performance challenges for steam and combined cycle turbine systems, and particularly for the expanding gas-turbine market.

According to Phillips 66 Lubricants, turbine oils must be formulated to minimize wear of valves and other components by preventing sludge and varnish buildup. Properly balanced chemistries reduce unplanned downtime by removing contaminants in the form of water, heat, and particulates, and by functioning as hydraulic control fluid.

For formulations, the type of metals used in gear drive applications is vital due to the possible presence of extreme pressure additives in the oil. Sulfur and phosphorus, extreme pressure additives, are corrosive to yellow metals such as bronze or copper. This will dictate what additive package to formulate for the gear oil.

Synthetic or mineral base oil is another choice to make. Synthetics will increase change intervals and viscosity indices while reducing oxidation rates. Mineral-based lubricants, however, will hold byproducts in suspension better and are typically less expensive. The revolutions per minute and the amount of load exerted on a particular gear set are two of the most important pieces of information when selecting the proper lubrication.

Gas-Powered Turbines

There are several key considerations for developing lubricants designed to work with natural gas-powered turbines and engines (Figure 5). Oil degradation is a key concern in the natural gas segment. The gas fuel combustion process results in a byproduct called oxides of nitrogen. This is referred to as nitration of the oil and must be monitored just as oxidation during analysis.

Sulfated ash is another unique aspect to natural gas and diesel engines. An elevated amount of sulfated ash may cause troublesome deposits on internal engine components. Compressor oils are another important product for industrial use.

Compressor oils can reduce typical wear and tear, and also can be used for cooling, sealing, and cleaning. Compressor oils have been in use since the early 1800s. To compress means to squeeze and therefore you can increase the pressure of a gas by reducing its volume or ‘squeezing’ it.

Gases are mostly compressible while liquids are not. That is the main difference between pumps and compressors. Pumps use the hydraulic principle of using incompressible liquids to transmit force while the compression of gases will increase its pressure. Compressors are used for many different types of gases throughout the power generation industry. It is an efficient way for energy to be transmitted.

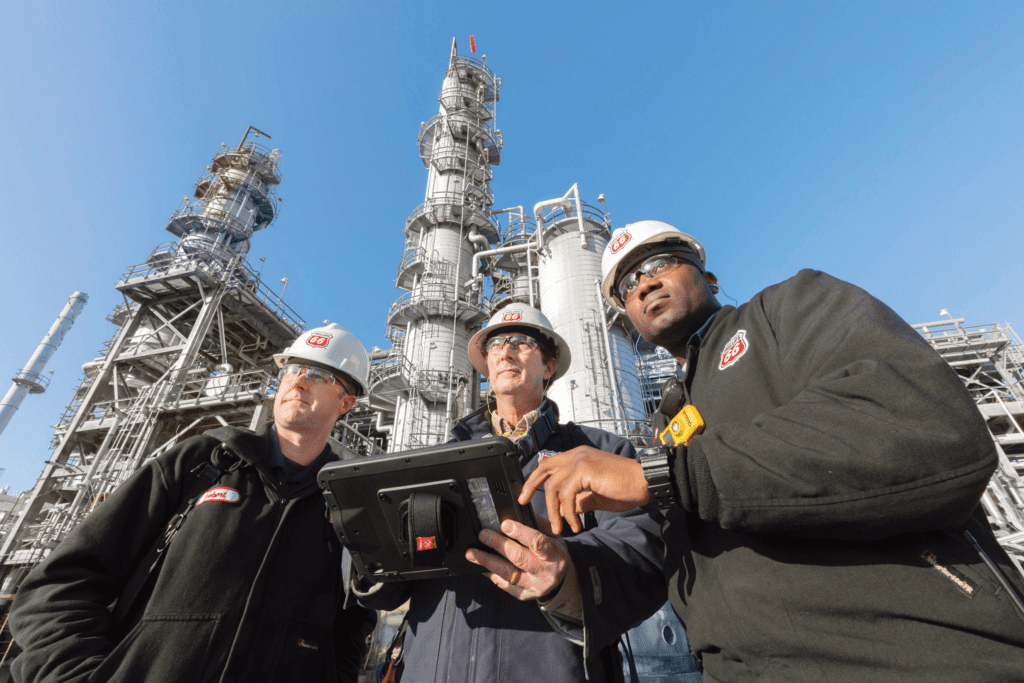

Lubricant products for power generation are numerous. Phillips 66 lists nearly four dozen on its website. With so many options it can be helpful to consult with your lubricants supplier to help select the best products for your specific operation. Phillips 66 has field engineers on staff to help you optimize your complete lubricant program for all areas of your operation.