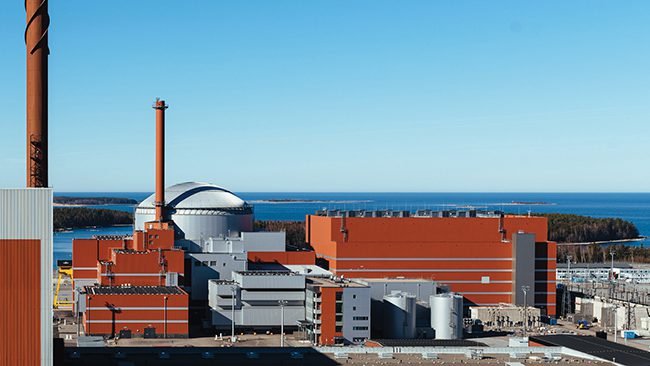

Olkiluoto Unit 3 Provides Carbon-Free Nuclear Power and Energy Security for Finland

|

As a first-of-a-kind project, Olkiluoto Unit 3 took more time to build than was originally expected, but the end result has proven worth the wait. Calling it the “largest single climate action” in Finland’s history is more than just a marketing slogan, as it is now providing reliable baseload electricity to serve about 14% of the country’s demand. Henceforth, it can also brag that it’s a POWER Top Plant award winner.

For people worried about climate change, nuclear power should be top of mind. Nuclear power is a carbon-free energy source that is well-proven, with reactors capable of supplying baseload power 24/7/365. Many nuclear power plants routinely operate at capacity factors greater than 90%, which ranks at the top of all power generating resources. For a world focused on cutting carbon emissions, nuclear power is a logical choice.

Leaders in Finland value clean energy. Remarkably, today more than 90% of the country’s electricity is produced from emission-free resources, with nuclear power being the leading contributor. And with the start of regular production from Teollisuuden Voima Oyj’s (TVO’s) 1.6-GW Olkiluoto Unit 3 (OL3) in April this year, the amount of nuclear power generated in Finland took a big step up. In fact, now about 30% of the country’s electricity comes from the three units located on Olkiluoto Island. With two additional units located in Loviisa, nuclear power accounts for close to 40% of the total mix.

Financial Troubles and Arbitration

OL3’s story began in the early 2000s. Jouni Silvennoinen, project director for OL3, explained, “In the Finnish system, we need parliamentary approval for any nuclear construction.” TVO received that approval in 2002. The company then initiated a turn-key fixed-price bidding process, which concluded with contracts being award at the end of 2003. Construction officially began in 2005, with a consortium consisting of AREVA GmbH (Germany), AREVA NP SAS (France), and Siemens AG (Germany).

OL3 is based on EPR technology. Originally, the EPR abbreviation stood for European Pressurised Water Reactor, but as the unit began to be marketed outside of Europe, the design became known as the Evolutionary Power Reactor. In either case, EPR is the common initialism.

The EPR is a four-loop design derived from the German Konvoi types and from the French N4. Designers expected it to provide power about 10% cheaper than the N4 and achieve about 92% availability over a 60-year service life. The EPR design has double containment with four separate redundant active safety systems, and boasts a core catcher under the pressure vessel. The safety systems are physically separated through four ancillary buildings on the same concrete raft, and two of them are aircraft crash protected. The primary diesel generators reportedly have fuel for 72 hours of operation, the secondary backups for 24 hours, and tertiary battery backup lasts 12 hours. The EPR is designed to withstand seismic ground acceleration of 600 Gal without safety impairment, according to the World Nuclear Association.

During the project, AREVA ran into financial difficulties, ultimately resulting in its breakup into three different companies—Framatome, Orano, and an AREVA business unit specifically focused on completing the OL3 project. Meanwhile, Siemens also underwent a restructuring during the project, spinning off its Gas and Power division into a separate company called Siemens Energy. As a result, Siemens Energy became part of the OL3 consortium. In the end, the project continued with similar players AREVA (Germany), AREVA (France), and Siemens Energy (Germany).

At least some of AREVA’s financial troubles stemmed from project delays and cost overruns on the OL3 project. These issues also led to contractual disputes and an arbitration case, which dragged on for roughly 10 years. In 2018, a settlement agreement was finalized, with TVO being paid €450 million and a trust being established with money allocated under French law, ensuring it could only be used toward completion of the OL3 project.

An International Workforce

At the peak of OL3 construction in 2011, there were about 4,500 workers onsite, and hundreds more working in engineering offices scattered mainly across Germany, France, and Finland. “The induction training was quite a big thing, because we had people from more than 80 countries onsite,” Silvennoinen said.

|

|

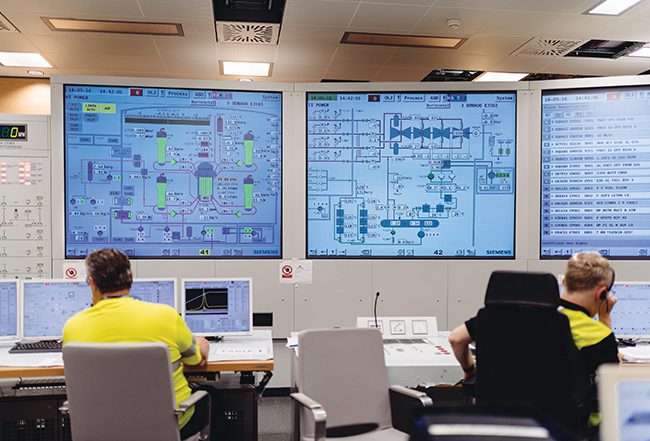

1. Olkiluoto Unit 3’s control room is filled with digital technology. Courtesy: TVO |

As previously noted, the consortium partners included French, German, and Finnish nationalities, but the official language for the project and the most common language onsite was English. “Bad English,” Silvennoinen joked. Thus, all the documentation, procedures, and main control room operator interface displays (Figure 1) were written in English.

“We put a lot of emphasis on communication. We needed to ensure that every worker could communicate with their superior in their mother language. We even made a huge language map to track communications. If we have a guy doing reinforcement, for example, who is he reporting to? Do they speak the same language? And then at some point in time, it was converted into English. But onsite some construction workers—quite many—didn’t speak English,” he said.

All workers also had to be entered into the Finnish tax system. “That was quite a big exercise,” Silvennoinen noted. It was important, however, to avoid fostering a “gray economy.” Ensuring a safe working environment with such a varied workforce was also important, so safety was a big part of induction training. “We set quite stringent standards, and, of course, there were mechanisms that if the safety standards were violated, there were consequences. Unfortunately, we had to remove some people from the site when they didn’t apply the correct way of working,” said Silvennoinen. The process was highly effective, as the project’s lost-time accident rate was less than two per million working hours, according to Silvennoinen.

Overcoming Challenges

Design delays were a big burden at the beginning of the project. “If you cannot plan your work a bit forward, it becomes difficult, for example, to arrange all the cranes or set concrete, etcetera,” said Silvennoinen. As the project progressed and designs were finalized, planning became easier.

The Fukushima accident in 2011 forced engineers to re-evaluate several design aspects, but in the end, the findings had minimal impact on construction. “There was this quite big challenge to review the safety basis of each and every unit—so called stress tests. We had to do that as well in the middle of the construction. But since the EPR is one of the first reactor types designed from the very beginning to cope with severe accidents, the changes introduced because of Fukushima were very limited. I would say 95% of the concerns identified were already addressed in the EPR design,” Silvennoinen said.

As anyone familiar with geography might suppose, Finland has very cold winters. (Outside of Reykjavík, Iceland, Helsinki is the northernmost capital in the world.) Pouring concrete in –15C (5F) temperatures, for example, and obtaining high-quality results can be a challenge. To overcome this, the project team collaborated with the sub-supplier and used temperature sensors to evaluate how the concrete was curing. This allowed actions to be taken to maintain parameters within strict guidelines, thereby achieving desired outcomes.

Achieving Top Performance

Plant simulators have proven to be beneficial to both operators and engineering personnel. “We have three plant simulators. One is for training purposes, one is for testing new features before they are introduced into the plant, and one is for all kinds of engineering activities,” explained Silvennoinen. “That has turned out to be a good idea too. Because this is a first-of-a-kind plant, and if it doesn’t work on the simulator, it probably doesn’t work in real life either.”

Digital operating manuals are also a somewhat unique feature adopted at OL3. The benefit of this is that operators are always assured of having the correct version on their screens. OL3 also benefitted from having OL1 and OL2 operating experience. “We could take quite a lot of procedures and things like that over to OL3,” Silvennoinen said.

“The unit performance since commissioning has been quite good. The plant has performed well—no shutdowns,” said Silvennoinen. “We started prepping for the final commissioning steps in March—operating now more than six months without any interruptions and the availability or the capacity factor is close to 100%. The only restrictions we have had were due to grid restrictions. It is a big unit on the Finnish grid—by far the biggest—and in some cases, we have had grid restrictions, for example, when we have a lot of wind power or consumption is less.”

After the lengthy construction period, OL3 couldn’t have come online at a much better time. The Russian invasion of Ukraine triggered an overhaul of European energy flows and markets. The 1,600 MW of urgently needed carbon-free energy from OL3 was a welcome addition to the Finnish grid. While much of Europe faced an energy crisis, Finland had the second-cheapest market price for electricity in 2022, trailing only Sweden.

|

And the citizens of Finland have taken notice. When the decision to construct a third reactor at Olkiluoto was made in the early 2000s, attitudes in Finland toward nuclear power were much less favorable than they are today. Ville Kulmala, communications specialist with TVO, provided a chart showing Finns attitudes toward nuclear power in 2003 were split almost evenly, with about 35% positive, about 32% negative, and the remainder being presumably neutral. In a survey released on April 20 this year, attitudes were much different—68% positive and only 6% negative. Kulmala said the main factor behind the popularity of nuclear power was climate reasons, but the positive publicity surrounding OL3’s startup certainly didn’t hurt.

Silvennoinen said he felt pride in the OL3 project on several levels. “I understand that this is a big, big thing in fighting climate change. We’re bringing a lot of new carbon-free—CO 2 -free—electricity into the market. Of course, from the company level, we can say that, yes, we actually did it. There’s a lot of talk, but we actually did it. On a personal level, this journey—working together with a very good team from our company together with the top nuclear experts from all over the world—it has been very fascinating. We have had some hiccups along the way, but now, we look at the results—the plant is extremely fine and nice, and it’s running smoothly.” The POWER editors agree and sincerely congratulate the entire project team on OL3’s selection as a POWER Top Plant.

—Aaron Larson is POWER’s executive editor.