Nuclear's Glimmer Ushers in Spate of Lifetime Extensions

Despite its ongoing war with Russia, Ukraine in early November gave state nuclear operator Energoatom the green light to operate Unit 1 of the South Ukraine Nuclear Power Plant for 10 more years. The approval from the State Nuclear Regulatory Inspectorate of Ukraine (SNRIU) means the 950-MW VVER unit, which entered commercial operation in December 1983 near the city of Yuzhnoukrainsk in the Mykolaiv Oblast of southern Ukraine, was granted before the unit’s license expires in December, and it means the unit can pursue an operational lifetime of 50 years.

While not in the immediate vicinity of the Eastern Ukraine conflict zones, where the most intense fighting has occurred since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the approval is a win for Energoatom, which has struggled with unprecedented uncertainty about the future of its 15 Russian-designed pressurized water reactors.

The war has frequently threatened Zaporizhzhia, Energoatom’s 5.7-GW six-unit nuclear plant in Enerhodar, on the banks of the Kakhovka Reservoir along the Dnieper River in southeastern Ukraine, as well as the 2-GW two-unit Khmelnitsky Nuclear Power Plant in the Khmelnytskyi Oblast of western Ukraine. In late October, a powerful explosion caused 26 broken windows at the Khmelnitsky plant, where one unit is operational, and the other is in planned outage, and briefly cut external power to off-site radiation monitoring stations. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), however, confirmed no impact on nuclear safety and security at the site.

Energoatom’s President Petro Kotin in a statement noted the approval for South Ukraine Unit 1 marks a milestone. “The uniqueness of this event is that, for the first time in Ukraine, all the necessary procedures and examinations to obtain the appropriate conclusion were carried out in accordance with Western standards and without a long shutdown of the power unit.”

Compared to previous practices that entailed shutting down the unit for up to 250 days, “This time, we went through all the necessary procedures to extend the life… while maintaining generation and providing electricity to our citizens,” he said. “The implementation of such global practice by Energoatom specialists and SNRIU experts significantly increased the efficiency and quality of our work.”

For Ukraine, the significance of life extensions is firmly pegged to the country’s quest for reliable power that is independent from Russia. But a spate of recently announced news related to the world’s nuclear fleet may be tied to a burgeoning revival for nuclear.

Bulk of World’s Nuclear Fleet Is More than 30 Years Old

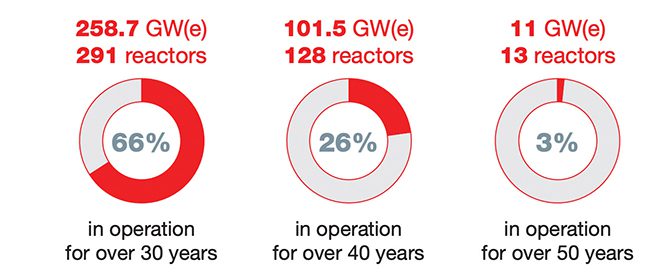

According to the IAEA, about two-thirds of the world’s 438 operating nuclear power reactors (291 reactors representing 258.7 GWe) are more than 30 years old. Many more are approaching, or have already reached, the end of their originally envisaged operational lifetime of about 40 years. The agency suggests 128 reactors—101.5 GWe—have been in operation for more than 40 years, and 3% (13 reactors totaling 11 GWe) for more than 50 years (Figure 1).

|

|

1. The world’s nuclear fleet is aging. About two-thirds of 438 reactors that are in operation today are more than 30 years old. However, at the end of 2022, a total capacity of 59.3 GWe (58 reactors) was under construction in 18 countries. Installed nuclear power capacity under construction has remained largely steady in recent years, except for in Asia, where there has been continuous growth, with 56.1 GWe (55 reactors) of operational capacity being connected to the grid since 2012, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) says. Courtesy: IAEA |

In 2020, the IAEA suggested that extending the global fleet’s lifetime by 10 years could have a “multiplying effect,” adding 26,000 TWh of low-carbon electricity generation. “That’s more than half the electricity produced in the previous 40 years by nuclear power, which took decades to reach its current output level,” it noted. But extending the fleet’s lifetime by a second decade to 60 years would generate an additional 31,400 TWh of electricity—representing almost 2% of the world’s low-carbon electricity produced between 2020 and 2080, it said.

The past few years, while characterized by a tumultuous period for energy, may have made that more achievable. In September, the IAEA revised its outlook for nuclear capacity, offering a “high case” projection to 873 GW in 2050—up 10% from the previous year.

“The realization of this projection would require large-scale implementation of long-term operation (LTO) across the existing fleet and nearly 600 GW of new build capacity in the coming three decades,” it said. Currently, the “energy crisis in 2022 has put on hold some decisions regarding reactor shutdowns, driving operators and regulators to implement actions to ensure safe and reliable LTO,” it said.

Over the longer term, the “continued and increasing demand for safe, clean, reliable, and cost-effective electricity generation is a strong driver for operators to extend the operating life of nuclear power plants by several decades through plant modernization and the enhancement of major equipment and systems to support LTO,” it said.

According to the agency, the aging fleet highlights the need for new or uprated nuclear capacity to offset planned retirements and contribute to sustainability and global energy security and climate change objectives.

“Governments, utilities, and other stakeholders are investing in LTO and aging management programmes for an increasing number of reactors to ensure sustainable operation and a smooth transition to new capacity,” it noted. “Even as the fleet ages, operational nuclear power reactors continue to demonstrate high levels of overall reliability and performance. Load factor, also referred to as capacity factor, is the actual energy output of a reactor divided by the energy output that would be produced if it operated at its reference unit power for the entire year. A high load factor indicates good operational performance.”

Recent Renewals Across the World

Among countries leading the lifetime extension charge is Japan. Japan’s Diet in May enacted legislation that allows nuclear reactors to operate beyond their current limit of 60 years—in large part to ensure stable power supplies and realize a decarbonized society. In November, Japan’s Nuclear Regulation Authority (NRA) granted a 20-year life extension to Kyushu Electric Power Co.’s Sendai 1 and 2, a combined 1.7 GW. The reactors are scheduled to reach 40 years in 2024 and 2025.

Kansai Electric Power Co. (KEPCO) in November, meanwhile, submitted an application to the NRA to continue operating the 780-MW Takahama 1 nuclear reactor for another 10 years. The milestone for the 1974-commissioned reactor is substantial, given that it is the oldest operating reactor in Japan (Figure 3). KEPCO restarted the reactor in August 2023 after it had been mothballed since the Fukushima event in 2011.

|

|

3. Kansai Electric Power Co.’s (KEPCO’s) Takahama Nuclear Power Plant in Japan’s Fukui Prefecture has four Westinghouse pressurized water reactor units with a combined capacity of 3.4 GW. Courtesy: KEPCO/Hirorinmasa |

In late October, meanwhile, Argentina’s Nucleoeléctrica Argentina submitted an environmental impact study to the Ministry of Environment of the Province of Buenos Aires to extend the life of the 362-MW Atucha 1 nuclear power plant by 20 years. The plant is scheduled to be decommissioned in 2024.

In the U.S., so far, six reactors—Turkey Point 3 and 4, Peach Bottom 2 and 3, and Surry 1 and 2—have secured regulatory approval to operate for up to 80 years. However, although the subsequent renewed licenses for Turkey Point and Peach Bottom are still in place, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission ordered that the expiration date of the subsequently renewed licensees be reset to the end of the initial period of extended operation. The direction will hold until the staff completes its re-evaluation of generic environmental issues for subsequent license renewal, which could be finalized in 2024.

Meanwhile, Monticello 1 and Virgil C. Summer 1 applied for subsequent license renewals this year, joining St. Lucie 1 and 2, Oconee 1, 2, and 3, Point Beach 1 and 2, and North Anna 1 and 2, whose applications are currently under review.

In February, Finland’s energy giant Fortum garnered approval to operate Loviisa 1 and 2, VVER-440 type reactors, through 2050. Fortum applied for new operating licenses for the 1-GW plant in 2022, after pushing for a controlled exit of all business with Russia. While the company still procures nuclear fuel from Russian firm TVEL, Fortum in November 2022 announced an agreement with Westinghouse for the design, licensing, and supply of a new fuel type for the Loviisa power plant. Fortum has said it intends to use the new fuel after Loviisa’s current fuel agreement with TVEL expires alongside the nuclear plant’s current operating licenses in 2027 and 2030.

—Sonal Patel is a POWER senior associate editor (@sonalcpatel, @POWERmagazine).