Hydropower Levels Under Careful Watch as Drought Ravages the West

Intensifying drought conditions in California and historically low water levels at the Oroville Dam on Aug. 5 forced the state’s Department of Water Resources (CDWR) to shut down the 644-MW Edward Hyatt Power Plant—the fourth-largest energy producer of all California’s hydroelectric facilities.

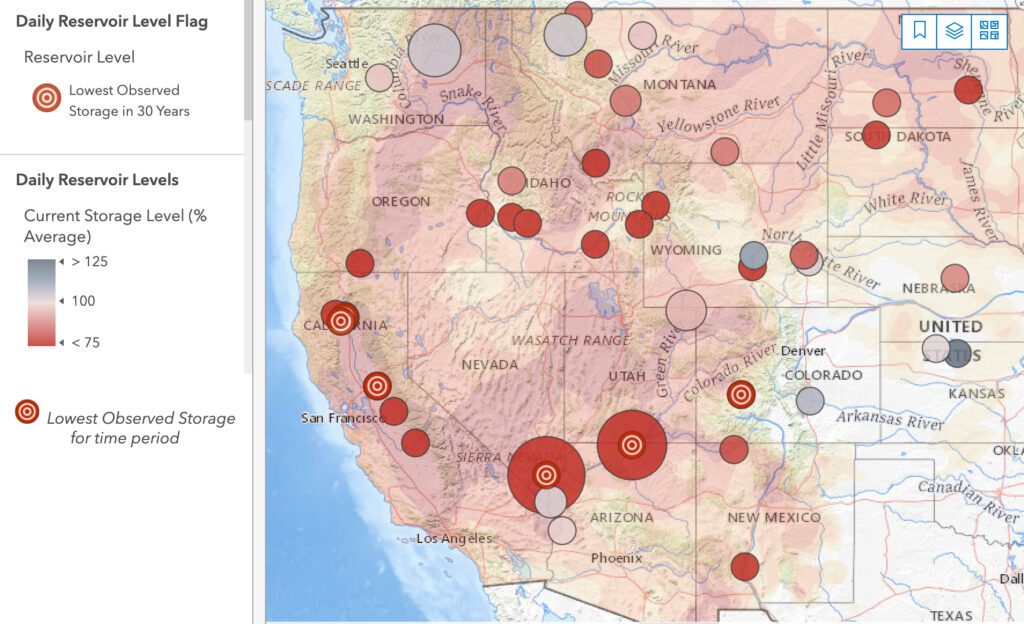

While the current drought is affecting 95% of the West, it is bearing down severely in California and in the Colorado River Basin. Multiple reservoirs monitored by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (USBR) are “substantially” affected. The federal agency reported on Aug. 8 that at least six of its 44 major reclamation reservoirs—including Hoover Dam and Glen Canyon Dam—have now fallen to their lowest storage values in the last 30 years.

The California Independent System Operator (CAISO) is “closely monitoring” reservoir levels statewide as it grapples with shoring up supplies this summer. However, it said the grid is currently stable, mainly because it anticipated the significant drought and the risk it posed for reduced hydro supplies.

Hyatt’s Shutdown Inevitable

The 770-foot-tall Oroville Dam—the tallest earth-fill dam in the U.S.—and Lake Oroville lie in the foothills on the western slope of the Sierra Nevada, and are one mile downstream of the junction of the Feather River’s major tributaries. As the CDWR notes, the lake stores winter and spring runoff that is released into the Feather River to meet the project’s needs. The project also provides pumped-storage capacity, 750,000 acre-feet of flood control storage, recreation, and freshwater releases to control salinity intrusion in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, and for fish and wildlife enhancement.

The Hyatt Powerplant’s shut down last week marked the first time the plant in Butte County, northern California, has gone offline as a result of low lake levels, the CDWR said. On Thursday, Lake Oroville was at 641 feet with 863,516 acre-feet of storage, which is 24% of its overall capacity and 34% of its historical average for this time.

The plant, however, has previously suffered outages for other reasons. Most prominently in 2017, heavy rains in the region triggered damage to the dam’s main and emergency spillways, and forced the evacuation of 180,000 people. The disaster shut down flows to the hydropower plant for three weeks and prompted a general national reckoning about dam safety. Reconstruction of the spillways at Oroville Dam was completed in 2019.

Along with the 1964-opened six-unit Hyatt underground pumping-generating facility, Lake Oroville houses two other power plants: the 3-MW Thermalito Diversion Dam Powerplant, and the 115-MW Thermalito Pumping-Generating Plant. CDWR said both plants, which are sited downstream from the Hyatt facility, will continue to operate at minimum levels for now because water releases to the Feather River are required for water supply, environmental and fishery needs, health and safety, and Bay-Delta water quality and flow requirements. The Hyatt Powerplant was taken offline safely and will resume operations when water levels in the reservoir return to elevations that allow water to again flow through the electrical generation turbines, CDWR said.

Hydro Losses Precarious: California Still Facing 3.5-GW Power Shortfall

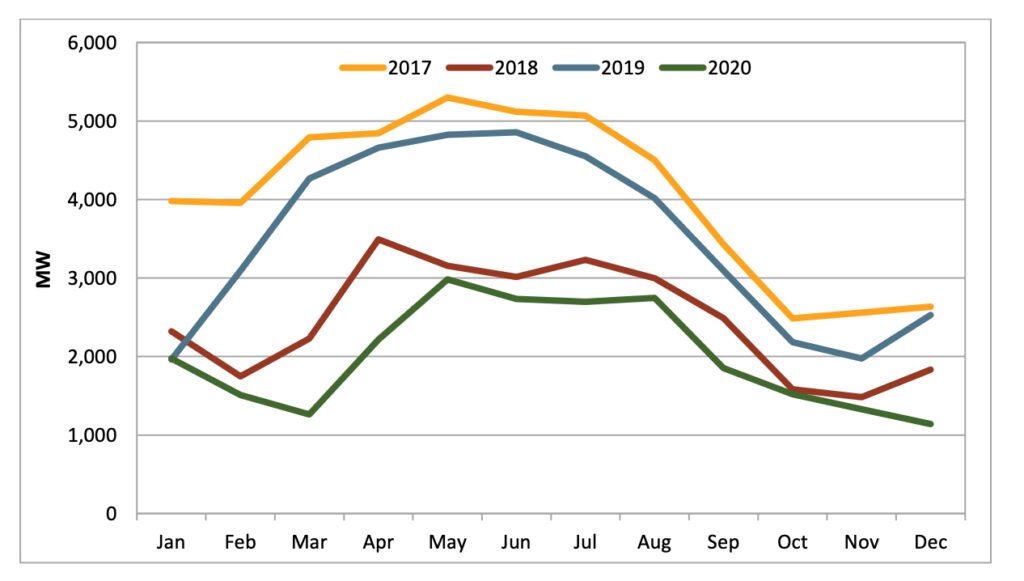

As CAISO told POWER on Friday, Hyatt’s closure may have been anticipated in its March 2021-published Summer Assessment, which foresaw a second consecutive year of “significantly lower than normal” hydropower supply. In 2020, according to CAISO’s freshly released 2020 Annual Report on Market Issues and Performance, total hydroelectric production in the grid operator’s footprint fell to 8% of total generation. That’s a 43% decline compared to 2019 and 19% lower than in 2018. Statewide snowpack as measured in April 2019 was already 50% of the long-term average, it said.

CAISO says year-to-year variation in hydroelectric power supply in California “can have a significant impact on prices and the performance of the wholesale energy market.” While run-of-river power generally reduces the need for baseload generation and imports, and hydro conditions affect the amount of hydroelectric power and ancillary services available during peak hours from units with reservoir storage, available hydro capacity can be hard to pin down.

In general, “water releases are often out of the control of the hydro unit operator, as water releases for residential, industrial, agricultural and fish habitat get higher priorities,” it explained. In 2020, almost all hydroelectric resources in CAISO were owned by California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) jurisdictional investor-owned utilities (IOUs), CAISO said. “The CDWR, along with [IOUs] operate dams, and they manage and optimize the water level as required by water level discharge requirements.”

CAISO, on the other hand, manages and optimizes the energy production from hydro generation—like any other resource coming into the market—via its day-ahead market, basing that optimization on the energy need during the day. “So in summary, we optimize the [megawatts] based on what the IOU and DWR put in our day-ahead market,” it said.

That essentially means: “One of any number of resources could make up for the reductions, depending on reservoir levels, dam releases, and energy bids coming into the market at the time, including those resources that bid in as imports,” CAISO said. “The ISO is closely monitoring reservoir levels and coordinating with the state and plant operators/owners.”

CAISO’s drought-related troubles are compounded by a raging wildfire season, repeated extreme heat events, and incremental resource delays. Reeling from its load-shed debacle last summer, CAISO in July set out to procure additional energy resources to ensure reliability for this summer using its “significant event” backstop capacity procurement mechanism (CPM) authority. CAISO on Aug. 6 published a list of 24 “designations” awarded outside of its resource adequacy capacity as a result of that effort.

However, Gov. Gavin Newsom on July 30 issued an emergency proclamation that suggests—despite CAISO’s CPM effort—that California still faces a 3.5 GW shortfall during peak periods this summer and fall. In summer 2022, the shortfall could grow to 5 GW.

The governor’s emergency proclamation grants emergency powers to the California Energy Commission (CEC), CPUC, and CAISO to speed up programs that will reduce demand on the power grid, including for industrial consumers and land-based electricity by ocean-going ships berthed in ports. More significantly, it may also suspend requirements in the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), the California Coastal Act, and the CEC amendment process for generators that the CEC deems could reduce the energy shortfall.

The CEC is also directed to specifically create an expedited permitting process, waiving requirements for geothermal, solar generation, and battery storage. Especially of note is that the proclamation suspends CEQA for generation of 10 MW or greater that meets certain conditions, and new or expanded battery storage of 20 MW or greater that can provide peak energy for two hours or more by the end of October 2022.

“Given its broad scope, the [proclamation] represents an effort to quickly increase available generation—even fossil-fueled generation—in the face of significant energy shortfalls that could lead to statewide power outages,” said lawyers from law firm Monchamp Meldrum LLP. “Even the temporary suspension of environmental review and permit limitations seen here is something the state has resisted in the past and may face opposition.”

Bureau of Reclamation Points to Worrying Levels at Reservoirs Across the West

Low-reservoir levels have specific implications for California, which in 2020 relied on 81.7 TWh of imported power for 30% of its total energy mix (272 TWh). Around 15 TWh—18% of total imports—was imported from large hydropower plants in neighboring states.

But according to the U.S. Drought Monitor (USDM), more than half of the West faces D3 or D4 levels of drought—its two most severe levels. “When both the spatial extent and severity of drought are considered, current conditions in this region are the most severe since the inception of the USDM in 1999,” USBR said last week. In addition, the high plains portion of the Reclamation domain—notably North and South Dakota—is also experiencing record drought conditions.”

USBR said the current drought is driven in large part by below-average precipitation across much of the West, coupled with consistently above average spring temperatures that have persisted into the summer months. Its effect on runoff water supply has been devastating.

“Except for portions of the Columbia River Basin, most basins are significantly below average,” it said. “This is unlikely to change substantially as the runoff season has largely concluded.”

In an interactive dashboard, USBR flagged six of its 44 monitored reservoirs across the West, indicating they are reporting the “lowest observed storage for a specific time period.”

These include Lake Mead-Hoover Dam, where storage stood at 9,026,386 acre-feet on Aug. 8, representing “59% of typical storage level for this date, based on the last 30 years of data.” According to USBR, about 56% of the 2-GW Hoover Dam hydropower capacity is allocated to California-based entities.

At Lake Powell’s Glen Canyon Dam, where a 1.3-GW power plant operates, storage levels were at 7,778,629 acre-feet on Aug. 8, or 49% of its typical storage level. In July, USBR began delivering (in efforts that will continue until December 2021) an additional 181,000 acre-feet to Lake Powell to combat its decreasing hydrology.

“Depending on the severity of the system emergency, the response from Glen Canyon Dam can be significant, within the full range of the operating capacity of the power plant for as long as is necessary to maintain balance in the transmission system,” USBR said. “Glen Canyon Dam currently maintains 30 MW (approximately 800 cubic feet) of generation capacity in reserve in order to respond to a system emergency even when generation rates are already high.”

Storage at Shasta Lake’s Shasta Dam in California, where the 663-MW Shasta power plant is located, was 1,388,402 acre-feet on Aug. 7, or about 46% of its typical storage level. The Shasta plant serves as a peaking unit. At another California reservoir, Folsom Dam, storage levels fell to 236,981 acre-feet on Aug. 7, or about 40% of its typical storage level. Generation from the 162-MW Folsom power plant has been dwindling since 2019.

—Sonal Patel is a POWER senior associate editor (@sonalcpatel, @POWERmagazine)