Rayburn Electric Cooperative faced three years of power costs in five days during the 2021 storm. The experience transformed the organization’s approach to risk, generation assets, and long-term planning.

When Winter Storm Uri swept across Texas in February 2021, Rayburn Electric Cooperative found itself staring down a crisis that would reshape the organization’s entire operational philosophy. The generation and transmission cooperative, which serves approximately 625,000 Texans across 16 counties northeast of Dallas, incurred three years’ worth of power costs in just five days.

“Bankruptcy was certainly one of the options on the table,” David Naylor, president and CEO of Rayburn Electric Cooperative, said as a guest on The POWER Podcast. “We were thankful we didn’t have to go that route. We were able to come up with a solution where we paid everything we owed—and then we took a hard look in the mirror and asked ourselves what we needed to do differently.”

That self-evaluation led to strategic decisions that fundamentally shifted Rayburn’s power supply operations, transforming the cooperative from an organization with minimal owned generation resources into one that now owns and operates a major power plant—with another under construction.

From Crisis to Acquisition

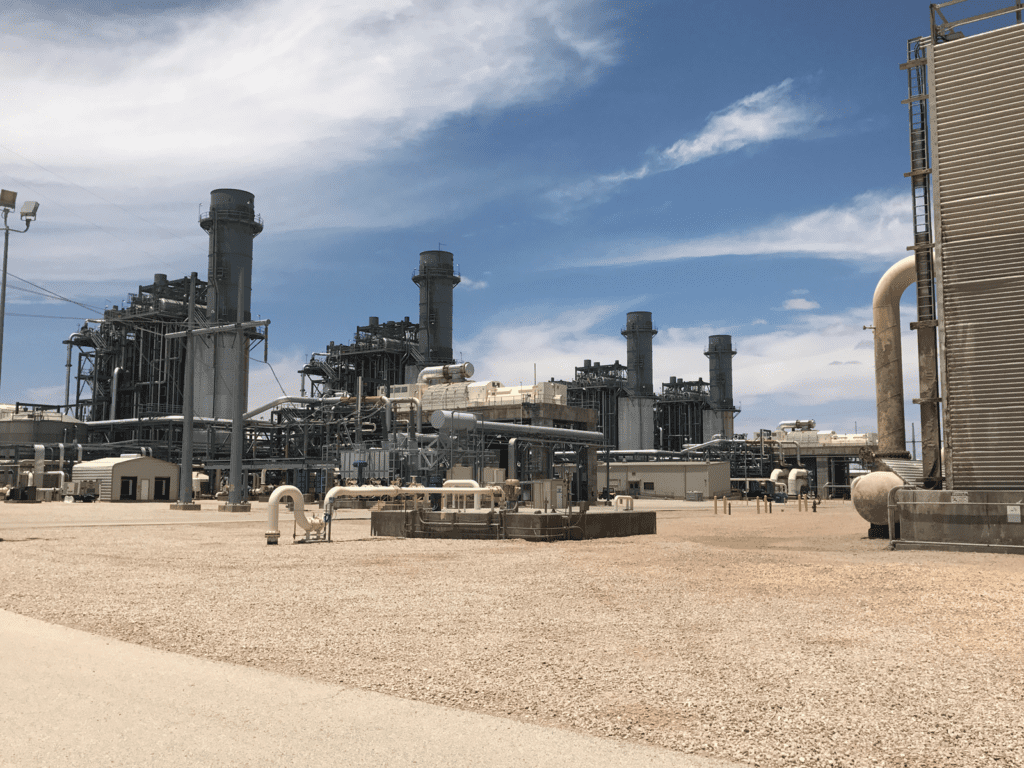

Within two years of Uri, Rayburn acquired the Panda Sherman Power Plant, a 758-MW natural gas–fired combined cycle facility located just outside the cooperative’s service territory. The acquisition doubled Rayburn’s balance sheet, but Naylor said the plant checked critical boxes that emerged from the cooperative’s post-Uri analysis.

“When we looked at who benefited from Uri—or at least came out of it in a solid situation—it was the people who owned generation assets, and whose units ran,” Naylor explained. “The Panda Sherman plant performed great during Winter Storm Uri. It had room for additional capacity if we wanted to expand in the future. And for someone that was staring bankruptcy in the face a couple years earlier, winning that auction over several private equity companies was a tremendous success.”

Building for Growth

One concern Rayburn had when acquiring the Panda Sherman plant—now called Rayburn Energy Station (RES)—was its size. Leadership initially projected the cooperative wouldn’t grow into the plant’s capacity until 2030 or later. That timeline proved wildly optimistic.

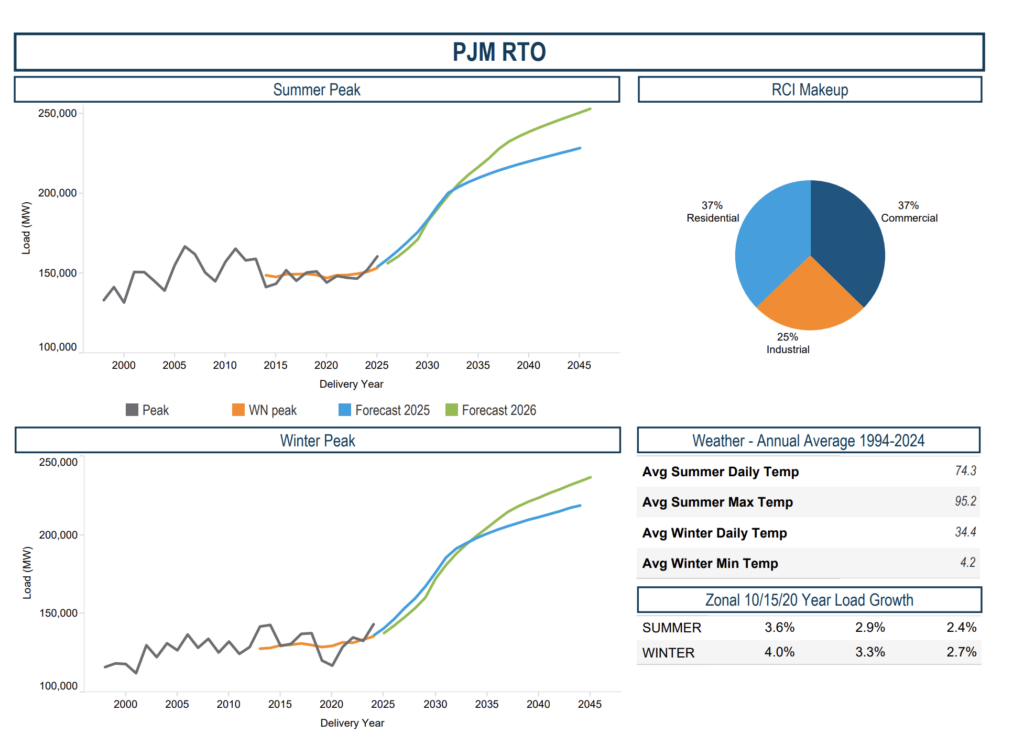

“We’re projecting 25% growth over the next 10 years, and that’s not counting any data centers or large loads—just normal organic growth,” Naylor said. “We grew into Rayburn Energy Station a lot faster than we anticipated.”

That rapid growth prompted Rayburn to begin construction on a second gas plant at the same site. The cooperative secured turbines and transformers under contract in late 2024, with a commercial operation date targeted for June 2028. According to Naylor, the timing proved fortuitous: suppliers indicated that waiting just a couple more months would have resulted in significantly higher costs and delivery dates pushed out by three to four years.

The project is supported in part by the Texas Energy Fund, a $10 billion pool of low-cost loans created by the Texas Legislature after Uri to incentivize new dispatchable generation. Of more than 125 initial applicants, only 17 were selected to advance—and Rayburn is the only cooperative among them.

Securing that access required legislative work. The original statute was written with investor-owned utilities and independent power producers in mind, where project-specific financing and outside equity are standard. Cooperatives, which are heavily debt-financed and member-owned, don’t operate that way.

“We had to educate the legislature on how co-op financing works,” Naylor said. “Fortunately, they recognized the issue and decided they really did want to make this available to all types of participants. That change will apply to any cooperative that wants to pursue that funding in the future.”

Workforce and Infrastructure Investment

The post-Uri transformation extended beyond generation assets. Rayburn’s workforce has grown from roughly 75 employees during the storm to more than 100 today. The cooperative invested heavily in linemen and created an apprenticeship program that accepts candidates straight out of high school, training them to become journeyman linemen.

Equipment investments have followed a similar trajectory. Rayburn added a heavy-duty crane, a mobile substation for proactive maintenance and emergency response, and a tracked bucket truck capable of reaching remote rural locations where conventional vehicles would get stuck.

“Most cooperatives, Rayburn included, are rural in nature,” Naylor said. “We’re not going down paved city streets to reach our facilities. We need equipment that allows us to access our system without depending on third-party contractors.”

Rethinking Risk

Perhaps the most significant shift has been philosophical. Before Uri, a one-in-100-year weather event was something many utilities acknowledged but didn’t actively plan around.

“Prior to Winter Storm Uri, most people would have said, ‘We’re not really worried about that—it’s an extreme event and just not likely to happen,’ ” Naylor recalled. “Uri drove home that those extreme events are very real and have very real impacts. People normally focus on what has the highest probability of occurring, but now we’re much more mindful of the extremes.”

At Rayburn, that mindset extends to other hazards as well, including wildfire risk mitigation and ongoing evaluation of pole inspection programs and potential reconductoring needs.

Broader Industry Impact

Uri’s effects rippled across the Texas cooperative landscape. The state’s largest generation and transmission cooperative filed for bankruptcy and ultimately had to divest its power plants, becoming a transmission-only entity.

“There’s a saying: if you’ve met one co-op, you’ve met one co-op,” Naylor quipped. “We’re all a little unique, but we try to help each other out. The managers talk to each other—share lessons learned. Uri definitely shifted and changed the co-op space in Texas.”

An All-of-the-Above Approach

While Rayburn’s recent investments have focused on natural gas generation, the cooperative maintains a diverse resource portfolio. It purchases the output from a solar project within its territory, with another solar facility expected to come online in the next few years. The cooperative also receives 60% of the power from Denison Dam, a hydroelectric facility on the Red River that has been part of Rayburn’s portfolio since the organization’s founding.

Wind, however, has been a tougher fit. With a service territory that’s 90% residential, Rayburn’s load profile doesn’t align well with West Texas wind patterns, which tend to peak at night when residential demand is lowest.

Advice for Industry Leaders

For utility leaders facing similar challenges of rapid growth and escalating risk, Naylor offered straightforward advice: don’t wait for the next crisis.

“Winter Storm Uri pushed us to be reactive when it hit. You’d much rather be proactive,” he said. “Make sure you understand your risk. Focus on those extremes, not just what has the highest probability of occurring.”

He also emphasized the importance of organizational flexibility. “At Rayburn, we have a saying—status quo is not company policy,” Naylor said. “Don’t let the way you’ve always done things get in the way of what needs to be done.”

To hear the full interview with Naylor, which contains more about Rayburn Electric Cooperative, RES and RES2, the cooperative business model, how nearby semiconductor manufacturing is affecting regional reliability, the broader post-Uri landscape for Texas co-ops, and more, listen to The POWER Podcast. Click on the SoundCloud player below to listen in your browser now or use the following links to reach the show page on your favorite podcast platform:

For more power podcasts, visit The POWER Podcast archives.

—Aaron Larson is POWER’s executive editor.

[Ed. note: Quotes have been lightly edited for clarity and length.]