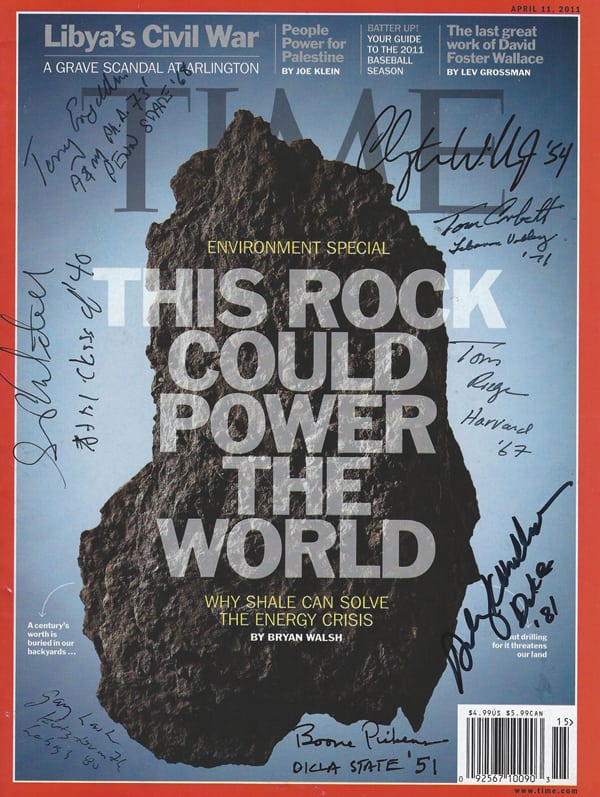

The de facto U.S. energy policy is to burn more gas, much of it produced using “fracking” technology. Huge volumes of low-priced natural gas have caused coal plant shutdowns, slowed renewable development, and undercut new nuclear plant development. Using more gas has also sent the nation’s carbon dioxide emissions into a downward spiral. Is the glut of natural gas too good to be true?

Now that an abundance of natural gas has become a seeming fact of everyday life, it’s time for the contrarian view to appear. Is the optimism over shale gas cockeyed and bound for a crash? Or is the methane ebullience an accurate reflection of new energy realities? There are no simple answers.

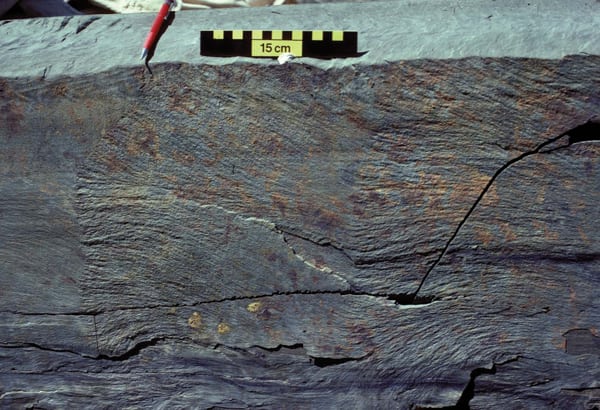

Recently, an arcane dispute among geologists became public, revealing an important rift over views about the future of natural gas. The geological flap raises questions about just how durable the shale gas boom will be and whether a long regime of low-cost gas can continue to fuel a dash to gas among electric generators that is clobbering coal, wrecking renewables, and negating the long-awaited nuclear renaissance. Unlike the earlier disputes over environmental issues related to hydraulic fracturing or “fracking,” which largely proved marginal and manageable, the current kerfuffle is over the performance of the wells themselves in delivering natural gas. Experienced geologists are wrangling over the rate at which wells in shale formations, created by horizontal drilling and fracking the gas-rich strata, run out of methane.

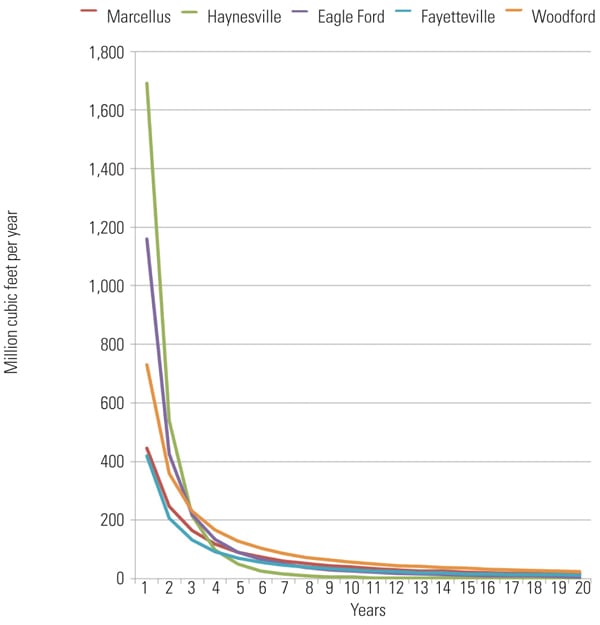

Some experts argue that shale gas wells decline rapidly, producing copious amounts of natural gas early and then quickly drying out, suggesting that the current glut of gas will decline just as steeply as it rose (Figure 1). Others respond that shale gas wells’ decline rates are nothing special and that fears of the gas running out are overblown. There is so much gas available, they argue, and the horizontal wells deliver for so long, that low-cost fossil fuel is guaranteed far into the future.

|

| 1. Steep well decline rates. Average production profiles for shale gas wells in major U.S. shale plays by years of operation. Source: Fig 54 EIA Annual Energy Outlook 2012, released June 25, 2012 |

Gas Skeptic

One major voice on the skeptical side of the emerging debate is that of Arthur Berman, a Houston-based petroleum geologist who is also a leading figure in the “Peak Oil” posse, a group of analysts who argue the U.S. has reached the bottom of its crude oil bucket and the rest of the world will soon follow. Berman writes frequently for “The Oil Drum,” a leading peak oil publication. Looking at U.S. shale gas, Berman says he sees a precipitous production decline coming as the need to drill new gas wells to replace rapidly declining production vastly outpaces the capacity of industry to deploy the rigs needed to drill.

In an interview with POWER, Berman argued that the boom in drilling shale gas wells has obscured a long-term decline in conventional gas supply. But a coming rapid decline in shale production, he said, will soon reveal the overall limits to the gas boom, and volatility and upward pressure could return to natural gas prices. “It’s not a problem for today or tomorrow,” Berman said, “but it is coming. Once we work through the current oversupply, if capital is not forthcoming,” prices will spike. The gas supply bubble will burst.

Because of the current gas glut, with long prices in the range of $3 per million cubic feet (mcf), drilling shale gas wells has tanked, noted Berman. Chesapeake Energy, the most bullish of the shale gas players, is selling assets and shifting rigs to drilling for oil because the company just can’t make money on $3 gas. “I can see a time not too many months away when we could see gas supply in rather serious decline,” Berman said, noting that “there is plenty of gas, but it takes a long time to shift momentum back” to gas drilling. At a 2010 meeting in Washington, as low gas prices were resulting in a decline in new drilling, Berman commented, “Shale plays are marginally commercial at best.”

Greatly complicating the supply equation, said Berman, is the nature of shale gas wells. “Shale wells decline 30 to 40% per year,” he said. “Conventional wells decline 20 to 25%. What most don’t grasp is how many wells it takes just to keep supply flat.”

In the Barnett Shale in Texas, where Berman is most familiar with the geology, he calculates that the annual decline in the gas resource is 1.7 bcf/day. In order to add to the net Barnett production, Berman says, companies would have to drill 3,880 wells, at a cost of $12 billion.

“We are setting ourselves up for a potential reduction in supply and price will go up,” said Berman. “I don’t know how much it will go up, and there is a check-and-balance with coal. There will be gas-coal switching if prices do go much higher than now.”

Bullish on Gas

But Penn State geologist Terry Engelder, the major domo of Marcellus Shale (see sidebar), doesn’t share Berman’s pessimism about gas supply and prices, or Berman’s assessment of the production decline of shale gas wells. “All wells decline,” Engelder said in an interview. “What distinguishes shale wells from conventional reservoirs is the percentage of gas delivered over a long period of time.” Shale wells, Engelder said, start producing at very high volumes, decrease considerably during the first year, but continue producing much longer than conventional gas wells, because the tight rock formations slow the release of the gas.

With shale gas, Engelder said, “You have a steeper decline curve initially, but a much longer period of production.” That’s a function of the tight shale reservoirs, “with inherent low permeability,” he said. “The gas takes longer to get” to the well head “but remains economic over a longer period of time.”

Here is where it can get pretty wonky. Engelder notes that the dispute with Berman and others in his camp who say shale wells decline too rapidly is a matter of hyperbolic production curves versus exponential curves. Engelder is in the hyperbolic school and Berman is one of the exponential advocates. If a well’s decline is hyperbolic, Engelder explained, you get a decreasing rate of decline year after year. The best data for eastern shale wells available, he said, shows a general hyperbolic decline over a 40-year period, versus a 25-year lifespan for conventional gas wells.

The advocates of exponential decline—including Berman and retired Canadian geologist J. David Hughes—argue that shale wells decline quickly after their initial high production, then level out quickly. Hughes puts the issue in the classic terms of resource depletion that environmentalists frequently use: “[O]il and gas are finite resources that are being consumed at unprecedented and growing rates,” and “the U.S. is the worst offender and is highly vulnerable to future energy price and supply shocks.”

The shape of the decline curve for horizontal gas wells can be very important for the economics of the well, notes an article (“Debate Over Shale Gas Decline Flares Up”) in the Oct. 10, 2010, Financial Times: “[I]f the pessimists/exponentials are right, then the ultimately recovered gas reserves from, say, the Haynesville deposits in Louisiana and Texas could be closer to 2 billion cubic feet (bcf) for the average well, rather than the 6 bcf some operators project.” This implies a market price two or three times the current level in order for producers to see a profit.

Balancing Opinions

Could Berman and Engelder both be right? “Art Berman and I agree on a lot,” Engelder told POWER. “Where we get into a difference of opinion is whether horizontal wells convert from hyperbolic to exponential. When that happens, you would get the same decline rate year after year, and the well would drain more rapidly.” The physical reason for hyperbolic decline, said Engelder, is that the wells do not interfere with each other, so the impermeability of the shale formations governs the decline rate. When the drainage area of the well reaches out to adjacent wells, and the well is not just draining virgin territory, he said, the decline rate might switch to exponential.

That’s not in the future for most of the giant black shale Marcellus formation, Engelder says. Drillers in the Mid-Atlantic region are well positioned to ramp up production rapidly and cheaply should natural gas prices go up even slightly. In Pennsylvania alone, says Engelder, more than a thousand wells have been drilled but not put into production. Of the wells in production, many are on drilling pads designed for six to eight wells each, but only two or three are producing. With this infrastructure in place, “it only takes a day or two to start drilling again.”

So Engelder sees little chance of the kind of price spikes that characterized the bursting of the conventional gas bubble of the 1980s and 1990s. “The reality is that the supply of gas in North America is so large it will take years for the price to recover,” he said. Producers and consumers both want stability, although consumers prefer lower prices and the industry higher. Engelder says the industry can live with $4 gas, while many are losing money or shutting in production at $3/mcf.

Today, Engelder and the optimists appear to be winning the argument over the future role of shale gas. Berman, Hughes, and the pessimists are a distinct minority among geologists. Skip Horvath, who for many years has run the Natural Gas Supply Association, representing the largest gas producers in Washington, says, “Art Berman clearly has the best intentions. He’s just out of step with the rest of the geological community.” (Read “Meet the Man the Shale Gas Industry Hates” at http://tinyurl.com/Art-Berman.)

Engelder is even more charitable. “Berman is not beloved by industry,” he says, “but he has things well worth thinking about in evaluating shale gas.”

Ultimately, the questions about shale gas supply and demand offer a good illustration of the basics of mineral resources economics, notes British science writer Matt Ridley in a paper titled “The Shale Gas Shock” (http://www.marcellus.psu.edu/resources/PDFs/shalegas_GWPF.pdf). Taking square aim at Berman and his concern about investors losing money on shale gas plays, Ridley comments: “It is quite possible that investment in shale gas firms will indeed prove risky as their very success drives gas prices down. But that will only happen if volumes of gas produced are high; and it does not mean that exploration and drilling will cease, for if they did, prices would rise again and exploitation would resume. After all, this has been the experience of the coal industry, the oil industry, and many other industries throughout history: success drives down prices, leading to business failures, but over the long term this does not prevent continuing expansion of production because low prices stimulate expanding consumption.”

New World Order

Devonian shale, and its now-accessible supplies of natural gas and crude oil, has been a revolutionary force in the U.S., and one that may be duplicated in Europe. While other factors—a slowly growing U.S. economy and a plethora of new Environmental Protection Agency rules regulating coal generation are two—are contributors, cheap methane is driving fundamental changes in the way America uses energy. The U.S. carbon footprint is making a smaller impact on the global environment, while bigger feet in China, India, and even Europe have emerged. Gas is pushing out coal, nuclear, and solar and wind power, purely on the basis of the cost of generating electricity. U.S. oil imports have declined substantially. The U.S. may soon be exporting significant amounts of natural gas to consumers in Europe and Japan.

Wall Street Journal columnist John Bussey wrote in the Sept. 20 edition, “During America’s Age of Imperialism, Henry Cabot Lodge famously said that ‘commerce follows the flag.’ Send over U.S. gunships, and U.S. business will be right behind. These days it may be the reverse. America’s shale oil and gas revolution—one of the biggest commercial bonanzas in generations—is itself shaking up the world order. As oil and gas flood into U.S. pipelines, relationships that defined how energy moved around the globe are shifting. How far that will go is open to debate.”

— Kennedy Maize is a POWER contributing editor and executive editor of MANAGING POWER.