In 2015, Germany added more renewable power than ever before, but now the government is putting strict limits on future renewables growth. As Germany’s Energiewende slows, some surprising competitors are jockeying for winning positions.

Germany’s Energiewende (energy transition) was adopted as policy beginning in September 2010, some six months before the disaster at Japan’s Fukushima nuclear plant, and full legislative support was achieved in 2011. Its key goals are to help fight climate change, reduce energy imports, stimulate technology innovation and the green economy, reduce or eliminate the risks of nuclear power, provide energy security for the nation, strengthen local economies, and provide social justice.

Now, five years into the “turnaround,” Germany has experienced several energy market and industry adjustments. As the country has implemented the Energiewende, both internal and external critics and supporters have pointed to different aspects of its implementation realities—especially regarding renewable feed-in-tariffs (see “Germany’s Energy Transition Experiment” in the May 2013 issue)—as confirmation of their diverging views on the merits of policy-prompted fuel changes.

Despite some short-term market and industry disruptions, the policy has been largely successful in achieving its stated goals, and public support remains strong. As reported in a January 2016–released report by Agora Energiewende, a Berlin-based energy think tank—“The Energy Transition in the Power Sector: State of Affairs 2015”—from 2012 to 2015, public sentiment in Germany has been strongly supportive of the Energiewende, with 90% saying it is important or very important.

Though geographically Germany is small, it is the world’s fourth-largest economy based on gross domestic product, according to the World Bank, so its energy transition is worth paying attention to.

Renewables Surged in Germany in 2015

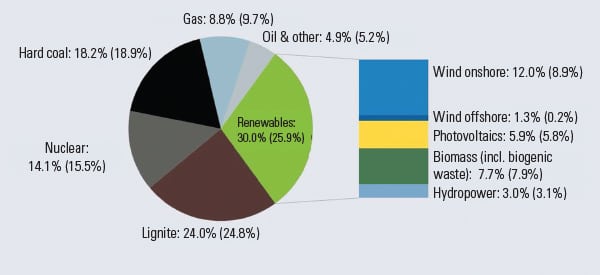

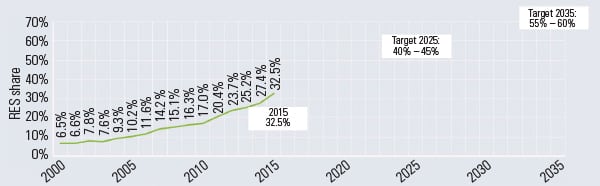

Even before the 2010 policy announcement, the use of renewables for power production was on an upward trend (Figure 1). Even so, 2015 was a banner year for Germany’s renewable energy sector. Green producers added more new generation—32 TWh—than ever before in a single year. While solar photovoltaic (PV) capacity is slowing (only about 1.5 GW were installed last year), wind experienced record growth of 50% year over year.

|

|

1. The path to more renewables in Germany. Renewable energy sources (RES) already supply about a third of the country’s electricity. Source: Agora Energiewende; data from AG Energiebilanzen 2015 |

Though all forms of wind power grew by nearly 29 TWh, onshore wind—often still being built in smaller developments as opposed to large wind farms—is currently booming as developers rush to complete projects before new auctions are rolled out in 2017. But the big growth by percentage was in offshore wind, where power generation jumped from just 1.4 TWh in 2014 to above 8.1 TWh in 2015 as the first of several large “windparks” came online. Throughout 2015 dozens of similar large windfarms were under construction in the North Sea, and even more capacity will come online throughout 2016.

The current German government policy is to grow the share of renewable electricity generation to between 40% and 45% of the total energy mix by 2025 and between 55% and 60% by 2035 (see Figure 1). Overall, renewables accounted for 30% of production—second to coal at 42.2%—generating roughly 647 TWh last year.

Though wind and solar power are intermittent, their full potential continues to be revealed. For one brief hour on the afternoon of August 23, 2015, the share of renewables reached its highest level ever when 83.2% of all power demand was covered by renewables.

While environmentalists and green energy proponents might herald this achievement, fossil fuel–reliant energy producers and those tied to carbon-based energy systems see this number as a harbinger of tremendous change ahead.

Putting the Brakes on Renewables Growth

The success of Germany’s Energiewende and the disruptions all this renewable energy are causing for the rest of the sector may be why the nation’s centrist government has quietly decided to slow the green trend down.

While some are celebrating the fact that Germany’s renewables crest above 30% market share daily, a few experts are starting to ring alarm bells that the green surge is over. At the end of 2014, the government adopted a limit, the country’s first ever, on the growth of renewable electricity. As part of the new policy, it’s likely that fewer small producers will be able to enter the market as larger investors take advantage of new policies designed to grow offshore wind.

With a high barrier to entry due to huge upfront costs, offshore wind may become the province of the same old-line companies that were once dominant in German fossil fuel generation, bet against the Energiewende, lost, and virtually went bankrupt. As renewables surge, its likely that the next generation of winners will be the ones who once wanted it least.

Merit Order and the Merits of the Energiewende

The German electricity market is dominated by four large suppliers that between them had a 67% share of the conventional power market in Germany as late as 2013. The “big four”—RWE, EnBW, E.ON, and Vattenfall—are involved in primary power production, distribution, and sales. Initially, these establishment power producers and others stoked fears that reliance upon renewables wouldn’t work.

Fears and Realities. These large traditional generators said renewables would increase prices, create grid instability, and force rolling blackouts. It’s now clear they couldn’t have been more wrong.

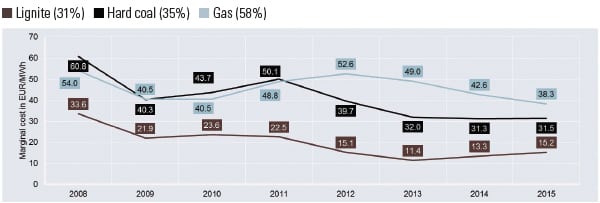

Prices have dropped almost 70% since 2008, and wholesale prices hit a 12-year low (below €30/MWh for year-ahead delivery, roughly $34/MWh) in August 2015. Wholesale prices have continued to fall this year, with Platts reporting on January 22 that “Baseload power for weekend delivery was last heard at Eur25.50/MWh,” and year-ahead power traded below €23/MWh “for the first time since early 2002.”

Also in 2015, Germany produced so much power—largely because of excess production from baseload plants—that the nation exported almost 10% of total production and became the second-largest electricity exporter in Europe. The Netherlands, Austria, and France were the largest takers because, as the Agora report notes, Germany has the second-lowest market power prices in Europe, after Scandinavia.

And, despite the transformation of Germany’s energy system, the nation has the second-most reliable grid in Europe. The average consumer’s annual outage period is below 12 minutes, according to the German Association for Electrical, Electronic and Information Technologies. (Meanwhile, in the U.S., the total number of minutes customers are without power has been increasing, according to a 2015 study by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and Stanford University. Though there is only one year of comprehensive data reported to the Energy Information Administration on outages, based on that data, InsideEnergy.org noted that in 2013 the average outage minutes in the U.S. were 200, with Vermont the lowest at 7 and South Dakota the highest at 1,100.)

Meanwhile, RWE and EON no longer are tied to the future of conventional power generation. Both utilities are restructuring—splitting off their fossil plants this year to focus on renewables, grid, and energy sales, which they expect will be more profitable.

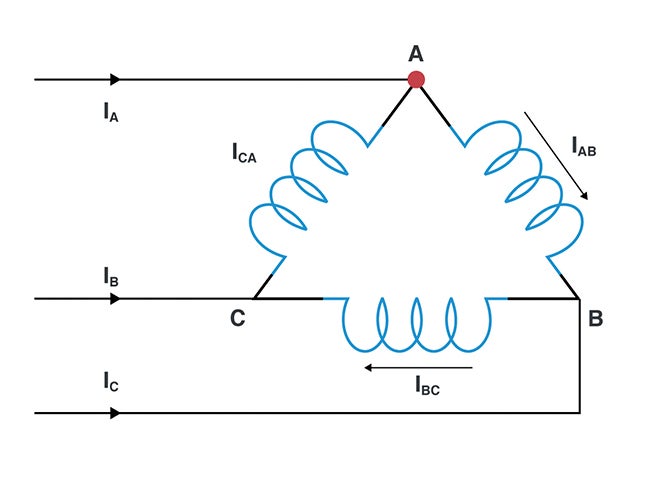

Merit Order Dispatch Consequences. Germany gets its energy from a bouquet of options (Figure 2). Which type of power is generated and dispatched first is determined by fuel input costs. The nation’s dispatch “merit order” states that as energy demand increases, new generation comes online on a cost basis. The cheapest fuel costs determine which power plants to ramp up first so that, in theory, the cheapest power is the next to be turned on.

The merit order approach was adopted in the 1990s, long before the rise of renewables. The Renewable Energy Sources Act or EEG, however, states that all renewable energy must be absorbed by the grid first. And, because neither the sun nor the wind send a fuel bill, fuel cost for renewables is zero. Given power demand, after solar and wind, hydro and biomass are next (though both are quite small), followed by nuclear (see sidebar). The next cheapest fuel to come online is lignite, then hard coal, and then natural gas (Figure 3). Overall, as more renewables come online, they keep pushing the share of fossil and nuclear generation down.

| The Nuclear Irony

A key plank in the Energiewende is the wholesale phase-out of nuclear energy by 2022. Although partially a response to the Fukushima disaster, this had been planned from the beginning. Currently, there are nine more plants to shutter. During 2015, another plant went offline, and nuclear energy’s share of the pie continues to get smaller, accounting for 14.1% in 2015. One of the ironic results of the shuttering of the nuclear fleet has been greater-than-anticipated reliance on coal, though in the future, Chancellor Angela Merkel’s ambition is to stimulate larger solar farms and offshore wind plants in the North Sea as a replacement. |

But there’s a catch. Under the German system, grid stabilization and energy redispatch (a request issued by the transmission system operator to power plants to adjust real power in order to avoid or eliminate congestion within or between control areas) are now actually performed by the larger, older power providers who just happen to own the vast majority of the centralized power plants that are getting displaced, going offline, and becoming increasingly unprofitable in the process. Regular dispatch is performed by the power market; only redispatch—due to insufficient grid capacity—is performed by transmission system operators and the big power plants. This creates an obvious conflict of interest, and it remains to be seen how the newly reorganized companies will carry out their complicated role.

Pricing Trends. One of the key arguments against the Energiewende both inside and outside Germany is that it has led to higher prices. However, the current market power price in Germany is at its lowest level in over a decade and actually declining. Even at €31.60/MWh in 2015, Germany had the second-lowest market price for power in Europe, after hydro-rich Scandinavia. Going forward, on the futures market, prices decreased even further: In the second half of 2015, power for the years 2016 and 2017 traded at less than €30/MWh.

However, one clear problem with current energy policy is that residential retail power prices are expected to actually rise slightly in 2016, due to increased levies and fees. Though wholesale prices in Germany remain rather inexpensive compared to the rest of Europe, costs for the Energiewende are partially paid by a special levy charged to electricity consumers for renewable energy. This levy was increased in 2014 to €6.35¢/kWh.

The Agora report forecasts that record low wholesale electricity prices will continue into 2018 at least. German “consumers will start to see gains in terms of a gradual and permanent decline in retail electricity prices over the next five to ten years as the near-term peak” government subsidies passes.

Coal Compromises

In any shifting economy, there are winners and losers. In the Energiewende, the old coal-fired plants and the companies that own them have been the biggest losers (though nuclear operators might argue with that assessment). The less these power plants run, the less money they make. In 2015, the nation’s lignite plants generated 24% of German power, second only to renewables with 30%, according to energy market research group AG Energiebilanzen. Hard coal accounted for another 18.2%.

Changing Fates and Roles for Traditional Generators. Establishment German power companies like E.ON and RWE initially dismissed the viability of renewables. While lobbying against green expansion, they instead invested in cutting-edge coal-fired power. Since then, the Energiewende has been a nightmare for them.

Rapidly decreasing utilization rates for conventional power plants are killing the financial returns of old-line power producers, along with those of the institutional investors who once relied on their profits. In late December, RWE even took the unprecedented step of mothballing its brand new billion-euro Westfalen-D coal-fired plant, deciding to close the future white elephant before it was even able to fire up (Figure 4). “The plant was damaged in the start up phase. But since then, citing a lack of financial perspective, RWE has decided not to fix the error but to deconstruct the brand new power plant. Though it cost over 1.4 billion euros to build, RWE will now sell it as scrap for less than 50 million according to reports,” said Christoph Podewils, Agora’s head of communications, in an interview with POWER. In other words, RWE’s creditors and management don’t believe that the return on investment for this now-stranded coal asset makes sense compared to investing more funds into offshore wind capacity.

E.ON similarly applied in 2015 to shutter two new, unprofitable gas-fired units. “The price decline on the wholesale power market has caused a crisis for conventional assets and there’s a significant excess supply,” said Marc Oliver Bettzuege, managing director of the Institute of Energy Economics at the University of Cologne, who has studied the markets for more than a decade. “The persistent price pressure changes the profitability calculations for the new construction or completion of power plants.”

As previously noted, after nearly going bankrupt after losing half their respective market values, the newly restructured E.ON and RWE are splitting their companies into different entities. One part of the new firms will ensure grid stability and run the fossil fuel side. The other will manage and generate renewable energy. Swedish-owned Vattenfall, which owns both several mines and power plants in Germany, plans to bundle and sell off its holdings this year as well.

Implications for German Coal Mines. Germany is the world’s largest lignite coal miner by volume (Figure 5). Though the government has committed to stop subsidizing hard coal production—now scheduled to be phased out by 2018, Germany’s 53 coal-fired power plants will continue to burn coal and generate electricity for years to come. Germany’s lignite resources are “highly competitive, aside from the externalities, without any government subsidies at all. So the challenge is fundamentally different for lignite than hard coal,” said Craig Morris, lead author of the influential Energy Transition blog and the author of two books on the Energiewende, in an interview with POWER.

In fact, hard coal is increasingly imported even as domestic production is curtailed. Furthermore, coal-fired power may be both unpopular and losing market share domestically, but exported energy from coal surged last year. To put it more directly, Germany is now increasingly importing coal mined from abroad in order to burn it domestically so as to generate excess electricity that is then exported. One of the few ways coal plants can still consistently make money is by exploiting the export markets.

Accounting for the energy that was exported, coal continues to provide roughly a third of the nation’s power and is the largest domestic fossil fuel source.

Precisely if and when all Germany’s lignite mines will be closed remains a very contentious question. Coal mining is still one the bedrock jobs in the former Communist East Germany as well as in other formerly industrial regions where unemployment remains higher. Those communities and the powerful labor unions there have formed alliances with conservative members of the Bundestag (German Parliament) to resist further cuts. As a result, Germany’s Federal Minister for the Environment Barbara Hendricks’ promises regarding the end of coal have become more restrained of late. “It’s clear that we have to have stopped using fossil fuels by the middle of the century, at the latest,” said the Social Democratic Party politician in mid-December. Though this tallies with what was just agreed to at the COP21 summit in Paris, timelines as to when mines will be closed and power plants shuttered continue to be pushed further out.

After months of debate, late last year as part of the grand compromise with both the industry and conservatives resistant to more renewables, instead of the government adopting a large levy on coal-fired power that would render it all but uneconomical, Germany will instead put 2.7 GW of lignite-fired plants into a power capacity reserve beginning in 2017, and then close them four years later, in 2021. According to Bloomberg, the reserve will enable the plants to operate when supplies are short only, and the facilities won’t be allowed to sell power on the domestic or export market.

Suffice it to say that most of Germany’s older lignite plants cannot ramp up and down quickly to address market peaks. Without the ability to produce power for export, these plants have no future. But new growth limits on renewables will protect the future of newer units that can quickly fire up and will ensure that their lights stay on for some time—and keep environmentalists fuming for decades to come.

More Compromises Ahead to Cut Carbon Dioxide Emissions

That said, the coal compromise should lead to an overall reduction in carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions of 11 million metric tons a year, the Economy Ministry estimated. Going further, the lignite industry agreed to cut an additional 1.5 million metric tons of CO2 emissions by 2018 in a scheme that has yet to be negotiated. Keeping the power plants in a reserve system will cost an estimated €230 million ($255 million) a year, said the German energy minister, Sigmar Gabriel, much of which will be paid for by consumers.

But Agora worries that the continued punting on coal, combined with a lack of “a consistent decarbonisation strategy for power, heat and transport,” will prevent Germany from reaching its climate protection goals. CO2 emissions in 2015 from the German power plant fleet were around the same level as in 2014 due to the constant level of coal-fired electricity, while total energy-related greenhouse gas emissions rose slightly. If the country continues down that path, it will not be able to get beneath the long-term limits it’s agreed to, Agora says.

However, according to the Merkel administration, Germany is already on the right path to achieving its new COP21 emissions pledges thanks to targets it adopted in 2007. Berlin’s pledge to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 40% by 2020 and at least 80% to 95% by 2050, both in comparison with 1990 levels, is still very feasible. “Our economy is in such a position that we can achieve an organized exit from coal,” said Hendricks, without giving a date as to when that might actually happen.

Either way, utilities can’t afford to cling to coal because Germany will have to cut 200 million tons of carbon by 2030, Gabriel, the energy minister, said. “But the real challenge is still ahead of us,” he told reporters at the deal’s announcement in Berlin.

As part of the recent coal compromise, the government also agreed with Bavarian and other state leaders to prioritize the construction of hundreds of kilometers of underground cables when adding new power lines instead of opting for massive new pylons. This is a significant breakthrough, as local opposition has long stalled progress on this issue. That said, such a major undertaking will only drive the costs of the Energiewende even higher. The goal is for completion of underground transmission lines to carry power from wind facilities in the north to industry in the south by 2022, when the rest of the nuclear units are due to be taken offline.

Offshore Wind Poised to Be the Future of the Energiewende

As laid out in the EEG, the expansion of renewable energy as an alternative to nuclear and fossil fuels is the primary aim of the current Energiewende. Today renewables are on a growth path to exceed their first, 40% target. Perhaps for that reason, new amendments to the EEG are going to rein in green expansion for the foreseeable future. According to Morris, the new EEG-determined target is that by 2025, Germany is to have no more than 45% renewable power.

This means that renewable energy “growth is to be cut almost by two thirds over the next decade,” he writes, as he fears the new scheme is taking a radical turn away from an “at least” 45% to “no more than” 45% approach. In the most recent amendment on December 8, the government’s new paper for EEG amendments states more clearly what was already hinted at in the 2014 amendments: “the government plans to slow down the Energiewende. For the first time ever, the 2014 Renewable Energy Act (EEG) introduced limits with intermediate corridors of 40–45 percent renewable power by 2025 and 55–60 percent by 2035,” reported Morris.

Moreover, the successful feed-in-tariff models used in the past will be replaced by auctions next year. As defined by recent amendments to the EEG, future renewable energy targets and expansion will be focused primarily on low-cost technologies based on “various types of renewable energy extension corridors.” What this means is that certain new technologies will be or could be given preference to help ensure that both baseload and grid security are ensured. This last point is key, as most of the recent amendments to the EEG are favoring the buildout of large-scale offshore windparks that may help with baseload capacity and offset more coal.

As more offshore wind generation comes online in 2016, the entire energy sector is being reevaluated. Unlike solar and onshore wind, which is mostly owned by small producers, communities or cooperatives, offshore wind is completely being developed by large companies. Some fear the winners in this new scheme will be the same fossil fuel companies that years ago bet against renewables—the same ones now investing in huge windparks in the North Sea while they export excess, mostly coal-fired power, to other nations.

Across the renewables sector as auctions are held for the remainder of PV and wind power’s allocated share, “the volume will be adjusted based on the current percentage relative to the maximum target.” Small-scale PV below 100 kW will continue to grow outside of the new limits. The new rules only apply to installations above this cutoff (the old threshold was 500 kW). But the situation is different for wind power, practically all of which will be auctioned relatively soon.

The problem is that Germany is already close to the 2020 renewables target, with 30% of generation already coming from green sources. “Over the next 10 years, that growth has been kept in check if the maximum of 45 percent remains standing. So annual growth of all renewable electricity must be reined in at no more than 1.2 percentage points,” writes Morris.

Morris also sees a threat to the future of smaller-scale production. For most of the Energiewende, hundreds of midsize and small energy producers, some owned by communities or even individuals, have entered the energy marketplace. But going forward, a large chunk of offshore wind power is to be auctioned off by 2020 regardless of the share of electricity. That will no doubt offset the available percentage for onshore wind. Because of the required upfront costs, only large, deep-pocketed companies have the resources to invest in the large-scale offshore wind farms of the future. As previously noted, Merkel’s government is looking to offshore wind to eventually replace a large slice of soon-to-be-retired nuclear and fossil fuel power stations as well.

The German government is hoping that a large chunk of the gap between today’s 30% and 2025’s 40% will be filled by offshore wind. Generating at roughly the same cost as nuclear, according to Agora, the current target for offshore wind is 6.5 GW, which could be increased to 7.7 GW by 2017. Last year, offshore wind alone grew by 6.7 TWh, equivalent to around 1.1% of German power demand. At that rate, offshore wind alone might take up practically the entire growth space left for renewables, says Morris.

Morris and others protest the shifting politics of this situation. Increasingly, “the people who called for and supported the Energiewende all along—German citizens—are being shut out of future growth. The entire short term transition is now being handed over to larger players, such as those who can do business in offshore wind and compete in auctions for large PV,” decried an alarmed Morris, who fears that the goals of the Energiewende won’t be successfully carried out “in the hands of those who did not call for it, did not support it, and do not believe in it now.” He fears that instead industry might decide that “45 or 50 percent renewable power is enough, and the ‘at least 80 percent’ target for 2050 will be considered something no longer worth pursuing.”

A Green Leader Falling Back

Either way, by controlling access to markets, fewer players will enter the power sector, allowing those big corporations already there to consolidate their influence and possibly the future direction of the Energiewende. How ironic that, despite December’s Paris agreement, green leader Germany has decided to slow down its transition away from fossil fuels at exactly the same time as most of the rest of the world is starting to accelerate in the other direction.

“By exporting more and more coal power to our neighboring countries, we will not be able to meet our climate targets. Agora Energiewende is calling for a complete coal phase out by 2040,” Agora’s Podewils told POWER. “We cannot be the country of the Energiewende and a coal country at the same time. That doesn’t work.” ■

—Lee Buchsbaum (www.lmbphotography.com), a former editor and contributor to Coal Age, Mining, and EnergyBiz, has covered coal and other industrial subjects for nearly 20 years and is a seasoned industrial photographer currently living in Germany.