The POWER Interview: New Directions for Aeroderivative Gas Turbines at PWPS

In a recent interview, Raul Pereda, president and CEO of PW Power Systems (PWPS), talked to POWER about the company’s long legacy as a gas turbine manufacturer, advancements in technology it has achieved over the past 60 years, and new applications for its turbines within a transitioning energy system.

No one can read a history of aeroderivative gas turbines without finding references to Pratt & Whitney (P&W), a company that is often credited with pioneering the first use of a jet engine as a gas generator in a stationary gas turbine.

Incorporated in 1925, the American company gained prominence in the piston-driven aircraft market before it made the leap into the burgeoning jet engine realm in the 1950s, mainly through military contracts for its 10,000-pound-thrust-class J57/JT3 engines—which were part of the world’s first generation of turbojets.

Within a few years, P&W had developed a larger derivative of those engines, the J75 (and its commercial iteration, the JT4), rated at 13,000 pounds of thrust, and in October 1958, the JT4 propelled American passengers into the commercial jet age in its inaugural flight from New York to Paris on a Pan American Boeing 707.

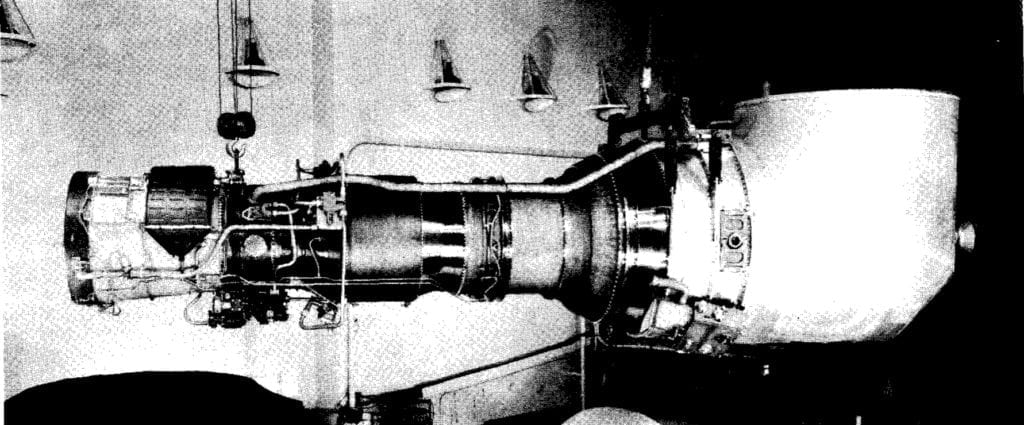

In the years that followed, P&W began exploring modifying its jet engines for industrial gas generation. By late 1960 (as Aviation Week reported in 1966), the company sold its first modified JT3 for use on a Columbia Gulf Transmission Co. system. And in 1961, in response to a request for proposal from the U.S. Navy, the company initiated development of the FT4A gas turbine engine for marine and industrial power plants. Design, construction, and tests of the engine, which was derived from the J75/JT4 turbojet, were quickly deemed a success, and according to proceedings published by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) in 1964, it opened up a vast set of applications in various industries, including for electric power generation.

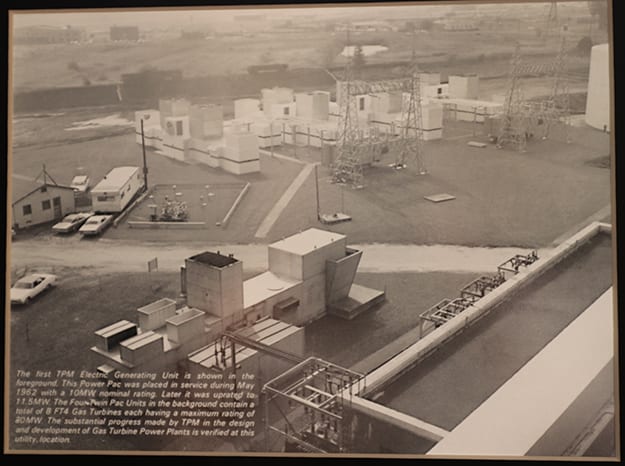

In early 1962, the first 10-MW turbojet “Power Pac”—comprising a J57 aviation gas turbine and an 12,500-kVa air-cooled electric generator—began operating at the South Meadow Station of the Hartford Electric Light Co. in Connecticut. The first industrial application of the FT4A engine arrived quickly afterwards in 1963, when Delaware Power and Light Co. in Wilmington, Delaware, installed a semi-portable package that included a natural gas–burning FT4A engine directly driving an Allis-Chalmers air-cooled 15-MW generator (13.5 MW at 80F, and 15 MW at 53F). The gas generator—the GG4A—kicked off a new line of business for P&W. It became especially popular in the wave of aeroderivative gas turbine generator installations after the Great Northeast Blackout of Nov. 9, 1965, when regional reliability councils forced utilities to bulk up on smaller, localized fast-start generating units with “black start” capabilities.

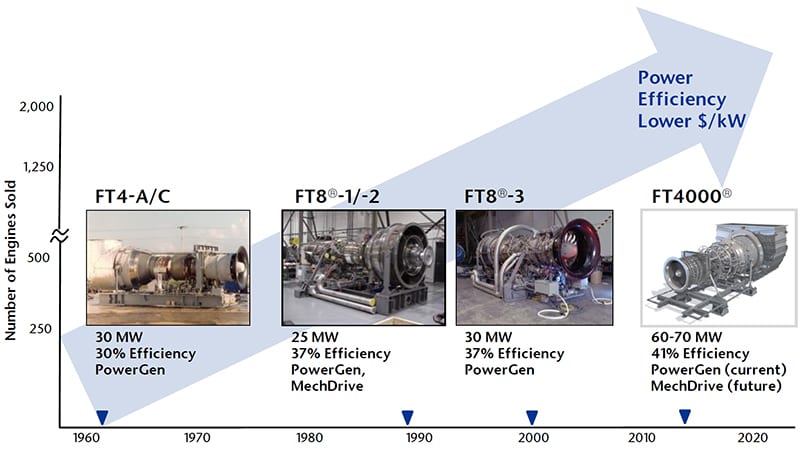

By May 2013, when Japanese firm Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (MHI) acquired the industrial gas turbine business unit of Pratt & Whitney—and rebranded it as PW Power Systems (PWPS)—the group had sold more than 2,000 aeroderivative turbines. PWPS functioned as a standalone subsidiary under Mitsubishi Hitachi Power Systems (MHPS), a joint venture MHI formed with another Japanese giant, Hitachi, in 2014, until it was absorbed by MHPS Americas in April 2018.

As Pereda noted, the stars of PWPS’s product lineup today are aeroderivatives with roots in its rich aviation history, including the FT8—which is derived from the JT8D, a turbofan engine Pratt & Whitney introduced in 1963—and the FT4000, an engine that is derived from the PW4000 turbofan engine, and which PWPS rolled out in December 2015. PWPS’s product portfolio today includes gas turbines from 30 MW to 140 MW in various package configurations—the FT8 MOBILEPAC or FT8 and FT4000 SWIFTPAC—as well as aftermarket services, including engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) for turnkey systems.

POWER: What were PWPS’s beginnings and how has it evolved in the power generation space?

Pereda: It’s a really interesting field for us. You know, our beginnings were really in 1961 as part of P&W, a jet engine company for aerospace. Back then, the jet engines—I keep calling them jet engines because that’s what they were, and still are—were primarily used for aviation. But engineers at P&W were toying with and working on a new product which was using that jet engine as a prime mover for the electric generator.

[Before the Great Northeast Blackout], which left about 30 million people without power in 1965, large power plants were dependent on the grid and existing power for energization to get restarted. So, you had basically the whole Northeast without power, and these guys at P&W said, ‘Hey, we’ve got to [develop] something that we can help you start independently,’ and coined the term ‘black start.’ Those gas turbines, the FT3 and FT4, were used to restart the large plants and get the grid back up and running. The company [that first deployed those turbines] was Hartford Electric Co. at the time, and the site is still here across the river from our offices [in Glastonbury, Connecticut].

And that just opened the industry’s eyes to the opportunities that could be leveraged with a flexible jet engine application to power generation at that point of time, for those specific needs. It was just really serendipitous, in a sense, that these engineers were developing this concept, and it’s turned out to be quite an industry. If you forward all the way to today, the technology provides quick-starting, flexible operation that traditionally is used for peaking applications. Our gas turbines can start in less than 10 minutes, and utilities use these now for spinning reserves as well as for their power needs.

POWER: PWPS is now part of MHPS, which has emerged as a formidable gas turbine market player, but evolved through a distinctly different historical channel. How did the company become part of MHPS?

Pereda: P&W, a United Technologies company, wanted to take their business in a different direction, so Pratt & Whitney Power Systems was vested into Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (MHI) and then subsequently, in May 2013, into the MHPS joint venture that was formed shortly thereafter, and became PWPS.

MHPS has many product lines related to power generation, but on the gas turbine side, MHPS is a prime portfolio consisting of the large, heavy-duty frame machines. The 501s, the 701s—units that typically would operate in combined cycle producing over 250 MW that utilities would use as baseload. MHPS really did not have aeroderivative gas turbine products in their portfolio. I feel that it was attractive—and it is, from the ability to present a product choice to customers. We can now offer customers anywhere from 30 MW of fast, reliable, peaking power to 250, 300, 400 MW of frame gas turbine technology. Our group here at PWPS was excited about that. We think that was a very good fit, and I think MHI felt the same as well, that it was attractive to combine the two.

POWER: How has your aeroderivative portfolio evolved over all these years? Have advancements always come as a response to customer preferences?

Pereda: You know, we’re always listening to our customers. As I mentioned before, traditionally, these units were designed with the philosophy to provide peaking support—when utilities needed to add that little bit of extra power, when folks got home and turned on their air conditioners, or when the weather got really hot. Gas turbines still continue to be used that way in many parts of the world. They’ve become more efficient, more reliable, and more environmentally friendly as those market, and environmental and political forces act upon gas turbines. What we’ve also seen is that the customers have driven us to some new designs.

An example is our FT8 MOBILEPAC unit. I think our first one that we delivered was the FT8 in 2004, though there were earlier versions. Customers sought solutions when they found themselves in situations where there were emergencies, or the need for quick deployment—where you didn’t have the luxury of taking 18 months to 36 months to install a large power plant. The MOBILEPAC is on wheels, and it doesn’t require a foundation. There really is nothing else in the world that allows you to have almost 100 MW in about 60 to 90 days.

We just delivered three MOBILEPAC units to Puerto Rico [on June 20, 2019]. We signed the contract on May 25, and delivered them to a port here in the U.S., and it took six days to get them to Puerto Rico. They’re ready to be running this summer. So Puerto Rico will have almost 90 MW of power ready for any potential issues they might have in the upcoming hurricane season. These units can also be moved easily, so if they are going to be installed in San Juan and they are needed somewhere else on the island, they can be moved, and it’s a matter of days, really. So that’s a packaging technology that we developed that has become very attractive and successful in the market.

We’ve done things on the environmental side with lower emissions, with lower noise footprints. Those initial units that ran in 1965 to restart the blackout would never be able to run today because of the noise they make and their emissions. Advances in materials, advances in designs, tools, advances in controls technology has allowed us to produce a unit today that is very environmentally friendly, easier to maintain, and lower cost for the customers.

We’re constantly looking at things. We’re looking today at potentially alternative fuels with additional enhancements to our units. Things like hydrogen, [liquefied petroleum gas (LPG)]. We’re seriously looking at both of those capabilities in addition to the natural gas and a liquid fuel that the engines [can burn].

POWER: Have there been markets for aeroderivative gas turbines that you had not foreseen at the outset?

Pereda: One area that we’ve ventured into, which was not really envisioned when these units [were] designed [60] years ago, is the oil and gas industry. We’re supporting a customer that does hydraulic fracking. In this case, what we’re doing is using the gas that’s a natural byproduct of the fracking operation. So, it’s not necessarily an off-the-shelf natural gas. Our engineers analyze the makeup of the gas—there’s probably six to eight variations, which is interesting—but we found we were able to run the units using these fuels. From an economic standpoint for our customers, we’re taking gas that was otherwise flared or gone to waste. They are using that to power our units to power their pumps to do the fracking. We started operations in January, and it has been very successful. They deploy these units—they are at the site for maybe a couple of weeks—and redeploy the MOBILEPACs. It’s just been a really fantastic operation and a huge success for this customer and ourselves.

POWER: When you deploy these units for fracking applications, do you modify the existing technology?

Pereda: We really haven’t had to do anything to the gas turbines. Without getting technical here, the calorific attributes of the fuel may not exactly be our spec, but, like I said before, we analyzed the samples that were given to us, determined that our technology could burn this fuel. Sometimes we do run into customers that have a lesser quality of fuel—whether it’s gas or liquid—and there are certain things you do as a pre-treatment. We are actively working on enhancements to the package specifically tailored to this new application.

POWER: Puerto Rico has no indigenous fossil fuel resources, though it has several LPG terminals. Federal laws, in particular the Jones Act, restrict foreign vessels from off-loading turbine components and natural gas between U.S. ports. [The Trump administration was reportedly considering a 10-year waiver of the Jones Act for natural gas shipping, as requested by the territory. But mixed signals have prompted Congressional lawmakers to introduce bills that would allow Americans to receive flexibility from the law’s rules.] What kind of fuel will the Puerto Rico units use?

Pereda: Initially, the units will run on diesel, but Puerto Rico is in the process of acquiring the ability to import more liquefied natural gas (LNG). I believe there’s … going to be an LNG plant put in in San Juan and perhaps another one in the southwest part of the [island]. One of the things Puerto Rico is moving toward, much like the rest of America, is renewables and cleaner energy. As part of their [integrated resource plan], there’s this significant amount of renewable energy, such as solar and wind. But those intermittent sources of energy have also created a market for our units.

In the old sense, it was ‘peaking,’ when it was [used to balance] a demand spike. But now, we’ve also created a kind of ‘reverse peaking’—which is peaking because supply spikes in a downward direction. As Puerto Rico moves forward to install more wind turbines and solar farms, they’re going to need a dependable backup, a system of power generation using clean energy as well as using natural gas. Our six engines, which are operating on diesel will eventually run on natural gas. And in this case, we do have different hardware that comes into play, depending on if the engine is running on gas or diesel fuel.

POWER: The concept of ‘reverse peaking’ is interesting—this idea that integrates backup as a larger system of intermittent generation. Backup power is gaining more significance as more jurisdictions ready for disasters, as a form of actionable resilience. Are you seeing more orders for resiliency? Orders that are proactive, versus reactive, which is to restore power after a disaster?

Pereda: I think so. You could argue that it’s reactive, but I might submit that it’s proactive what Puerto Rico is doing. They did have the tragedy with Hurricane Maria, and the impact that it had on the island. And they certainly reacted to that. They went out at an individual person level. You know, many folks were just trying to get their hands on whatever small generators they could grab, or went out and leased some larger gas turbines. It’s amazing to think that was almost two years ago. I might argue, historically, that’s probably all they would have done and not think about the next one. So I have to give credit to the leadership of [Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority] for thinking, ‘lets not restore the country back to pre-Maria, but let’s talk about and let’s act on putting some plans in place to be proactive and get these units.’

There’s certainly recognition that with renewables, the resiliency of the grid is going to have to be addressed. We won an order in Israel last year that’s 400 MW. It’s a peaking plant to support Israel’s push toward renewables. It’s a proactive way to address the growth in renewables and the intermittent energy that is a consequence of those. Ireland is also a country with similar needs. [Recent discoveries of oil and gas in Irish waters in the Atlantic Ocean over the past 15 years] enables that [prospect]. I think utilities are still trying to decide what their right portfolio mix is, but we are seeing spots around the world where developers, [independent power producers], and utilities are thinking about not just disasters and natural emergencies, but also the move toward renewables, and how they supplement their portfolio with fast, flexible gas turbines.

POWER: There’s been an immense push for energy storage lately, and falling prices of batteries have prompted developers of all sorts to consider large-scale energy storage solutions. Some are even pairing gas turbines with energy storage to offer a solution to renewable intermittency. Does PWPS view energy storage as a disruption to the future of small gas turbines?

Pereda: Disruption is not a bad word. All of these things throughout the history of any industry really—they’re wake-up calls to reevaluate, reassess your product, and make sure that you find and refine your place in the market. For us, it’s a complimentary technology. For sure, the conversation today is much different than it was 20 years ago. Really nobody was talking about solar, wind, and battery. Energy storage via battery is something that I agree with you is going to become more affordable and more prevalent.

There are still limitations when it comes to batteries—just fundamental things, like space considerations. You can put 30 MW in a really small footprint, whereas if you wanted to do that with batteries, they would take a significant amount of land. And I’ve seen communities pushing back on that. I’ve seen it here in New England with wind farms; people don’t want them when they look out the window … and we’ve seen it in California as well. But I think it’s going to happen. I think we’re just at the beginning of this and the solutions will come. For us, I think it’s going to be, as you mentioned, pairing current gas turbines with batteries. We’re talking to a customer in Europe about doing that for some of their gas turbines that are already installed.

I think we’re going to continue to look for those opportunities. You mentioned that MHPS is doing some things with hydrogen storage. That’s something that we could take advantage of because our equipment will be able to burn hydrogen. But on the battery side, I think we’re going to continue, and we’re going to find solutions to work side by side with batteries. Batteries need to be charged, and there still needs to be a source of power. In some cases, it will be renewable power when it’s available, but in some cases it’s going to have to be fossil fuel.

POWER: Where are you sinking your research and development dollars today?

Pereda: Today, we’re looking at the more immediate needs. The things in front of us, I would say, are performance driven. We’re looking at our current products, the FT8 and the FT4000, and we’re developing improvements that increase performance, power, that increase efficiency of the gas turbine. Efficiency directly correlates to emissions as well. So we’re looking at—within the same footprint—making a more powerful gas turbine, a cleaner gas turbine, and a more-efficient gas turbine. With that, we’re also making sure the reliability of the gas turbine is not impacted.

And then beyond that, we’re looking at fuels. We’re also looking at controls and advanced diagnostics technology from the standpoint of the customer’s life-cycle cost. The ability to monitor, the ability to predict, the ability to then take preventative action, and more-efficient maintenance action, help us become more competitive.

POWER: Are there any specific points as they concern the gas turbine market or technology today that you think are overlooked?

Pereda: Yes, there is one area: the constructability of a plant. [Our company] in particular … offers packaging and installation, including the engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) elements of it.

One thing that we’ve all done, in addition to looking at [the] gas turbine itself, is we’ve looked at our package. Our package underwent a pretty major redesign about 10 years ago. We’ve continued to make improvements, but we have, as part of PWPS, a company—our own group—that does EPC work and does installation. There’s a couple of things that differentiate us. One is what I think is the best customer support in the world, and we can talk about that some other time. But I think also the ability that we can offer you a turnkey solution. With many of the opportunities that we’ve secured, we offer a full turnkey solution to our customers, and it’s often overlooked. But it’s really important for customers to be able to come to us for one-stop shopping.

We can take care of all the balance-of-plant equipment, like transformers and field treatment—both ins and outs of a plant. Our customers have one point of contact when it comes to a contract. For us, it’s something that also enhances our flexibility. It gives us a little bit more of a leg up on our competition in terms [of] what problems we can address for the customer. It’s something industry-wide—it’s something that all OEMs [original equipment manufacturers] are focused on—but I think we’ve done a really good job with our equipment.

—Sonal Patel is a POWER senior associate editor (@sonalcpatel, @POWERmagazine)