The Art of Self-Assessment: Why Your Organization Is Not Improving

It’s not uncommon for organizations to go through performance cycles from good to bad, and hopefully, back to good before repeating the process. However, a well-conceived and consistently applied self-assessment process can break the cycle and help organizations maintain peak performance.

The catch phrase “People are our most important asset” seems to be lesson one in the “Things Bosses Say” handbook. If the cliché is true, and organizations believe it, then why do so many fail? Before you turn the page, let me promise you this is not just another feel-good, how-to-treat-people-well article. In fact, this article might make you uncomfortable. If it does, you NEED to keep reading.

People ARE Your Most Important Asset

Truthfully, people are the most important asset in any organization. It really does not matter the type of business or how large the organization—a highly functional team is key to success. The ideal organization will function autonomously, even in the absence of management. So, how do you as a leader build and, more importantly, maintain that kind of team?

The answer lies in the art of self-assessment. You have probably been taught many times the importance of continuous self-improvement—the ideology that an organization consistently strives to be better than it was yesterday. Many organizations push this rhetoric and truly believe in it, but still fall short. Why? Because they don’t know how to evaluate their current performance and use that as the benchmark for improvement.

This lack of proactive self-assessment is why performance typically occurs in cycles. It has been said, “Strong men create good times, good times create weak men, and weak men create hard times.” This isn’t just philosophy, it’s human performance, and it has been proven time and time again, across all types of organizations.

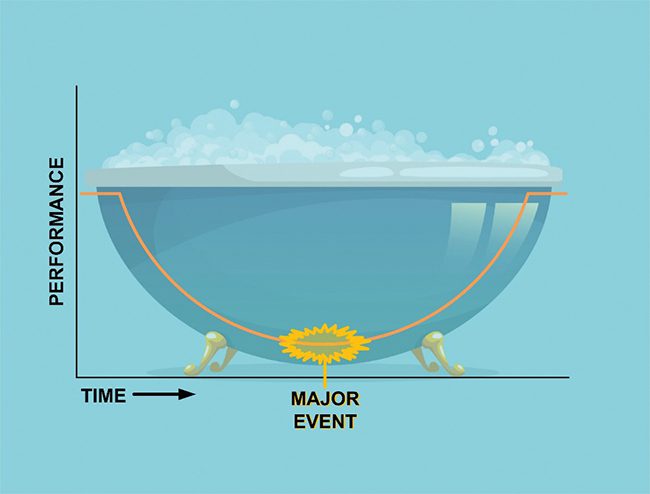

When I was a Naval operator, this cycle of human performance was dubbed the “Bathtub Effect” (Figure 1). It followed the same cycle. An organization is functioning at peak performance, people know what they are doing, they are keen on identifying and correcting problems, and the culture of continuous improvement is strong. Over a period of time, the length of which is affected by both personnel turnover and human memory, the team’s performance starts to slip, people become lax, and standards begin to waiver. This often goes unnoticed over the course of a few years, as the overall success of the organization masks the small problems, and issues that arise are often dismissed as one-offs. Thus begins the downward slope of the bathtub.

|

|

1. The “Bathtub Effect” illustrates the cycle of human performance from good to poor and back to good over a period of time. Courtesy: Fossil Consulting Services |

Eventually, the small problems begin to add up. New personnel join the organization and are trained in the ways of a now depreciating culture. The people doing the training are often blind to the negative value they are introducing because they remember the “good times,” but not why the times were good. This cycle continues and standards lower further, until some event or accumulation of events cause a major problem. Welcome to the bottom of the tub.

We’ve all seen it. Administrative requirements slip, regulatory requirements are missed, worst case, an incident occurs that results in injury or loss of assets. These are “the bad times.” At this point, EVERYONE begins to pay attention and someone will want to find out: “How did we get here?” Leaders are often replaced, new personnel are brought onboard, and A LOT of attention and money is put into improving the organization. Now, we begin the upslope of the bathtub. The corrective actions put in place hopefully restore peak performance, and we once again operate at the top of the bathtub until the cycle begins again.

How do you skip this process, and the personal and financial pain that it inflicts? You have to learn how to perform objective self-assessments, and make them a priority in your day-to-day operations.

Complacency Is the Enemy

The hinge-pin of self-assessment is the phrase “Expect what you inspect.” It is common for leaders, especially during a period of peak performance and success, to assume that the organization is functioning exactly the way they think it is. We assume people know what we think they know. THAT is the trick. If you are to assume anything and be successful, you MUST default to the assumption people are NOT performing as you expect and DON’T know what you think they know.

Let me pause and explain something. This is not an attack on your people and should not be approached negatively. In fact, I’d argue the exact opposite. People want to perform well and they want to know what they need to be successful. It is the role of leadership to ensure expectations are clear and knowledge is provided.

At this point, you’re probably thinking, “I have instructions that provide clear guidance on what I expect of my people.” I bet you do, and that is fantastic. In fact, it’s the first step in making your organization successful. You have to provide clear communication of what is expected. However, when was the last time you validated those expectations? Not only whether or not they are still valid or applicable, but that they are being followed? Validation is vital to success. Without validation, standard operating procedures (SOPs), instructions, memos, etc., are just words on paper.

Your car manufacturer expects you to check your oil, tire pressure, and battery before any trip; it’s written right into your owner’s manual. I bet you’ve rarely done that. The art of self-assessment requires you as a leader to determine what is important to the success of your organization. What procedures need to be followed? What knowledge do your people need? What culture do you expect? Once you know these things, you must take the time to go out and see if these things are in place and being followed.

Again, this is NOT a negative program, but most organizations are unsuccessful at implementing it because they make it negative. What do people think when they hear, “The Boss is coming to watch us X, Y, and Z”? They assume something is wrong, and someone will be reprimanded. If you make your self-assessment program negative, what you will get is a false impression, because people will act differently to ensure they keep their job.

Positive Self-Assessment: The ADDIE Model

Implementing a successful self-assessment program first requires an organization to decide what is important to their success. Secondly, it must recognize that human beings do not typically do things wrong on purpose, especially not at work. Then, managers must get into the field and evaluate.

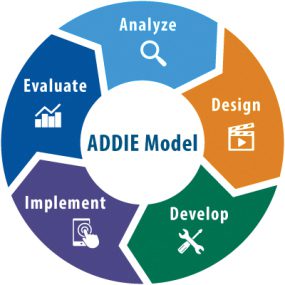

You may be familiar with the “ADDIE” model for instructional design (Figure 2). The self-assessment process is a continuous implementation of this model.

|

|

2. ADDIE stands for Analyze, Design, Develop, Implement, and Evaluate. Courtesy: Fossil Consulting Services |

The first step in a successful evaluation is to review your own requirements. What does your SOP say? What are the expectations and procedures? What are the applicable regulatory requirements? Make a list. This has to be objective, not purely a matter of opinion. Start with the basic skills required to perform your organization’s functions, those are often the first skills both management and employees become complacent too.

The second is to go look. This does not have to be a big production. You are simply going to the source and seeing how things are being done. In order for this to be successful, you have to stress to whoever you are observing that you are simply trying to see how things are done. I encourage you to “act dumb” during this portion of the assessment. You’re there to learn what is perception and what is reality, so you can address the gaps.

During your assessment, ask questions that will help you determine the reasons for any gaps you discover between your expectation and reality. You might ask: “How do you know what to do here? Did you get any training on this or did you have to figure it out on your own? Does this work the way it is supposed to? What would you do to improve the process?” Take a lot of notes—both good and bad. Throughout this process, remember that just because you know something, doesn’t mean everyone else does.

I’d like to pause here and provide a real-world example. In the Navy, I operated and maintained propulsion equipment on aircraft carriers (turbines, pumps, generators, etc.). One of our most basic skills was taking and analyzing lubricating oil samples on the turbines, which was performed daily. As you can probably guess, the samples were usually satisfactory. My last job in the Navy was evaluating training and operations for all the aircraft carriers on the East Coast. One of the first places I would go look for problems was the oil sample rack. Every single time I looked, I found at least one bad sample that had been analyzed as “satisfactory.” When I questioned the operators, I would identify huge knowledge gaps in how to properly take and analyze lubricating oil samples. Again, this was a daily maintenance item, but there was a common knowledge deficiency in this routinely performed task.

On more than one occasion, the results of the samples had to be adjudicated before we could continue the inspection. On nearly every occasion, management would try to wave it off as a “single point failure.” To prove my point, I would then question about 10% of the operators on the requirements for oil sample analysis. Nine times out of 10, I would get zero correct responses from those questioned. Management was rarely happy with my results.

Using What You Learned

Okay, so now you’ve observed reality, and you were not happy with the results. Perhaps you have an explicit procedure for how something is to be done, and it was not used. Perhaps you are not meeting a regulatory requirement that could cost you in fines. Now, you have to ask, “Why does this gap exist?”

- ■ Be objective. Is this a true one-off? Perhaps it really is just a problem with one employee.

- ■ Could this be an organizational problem? Do you need to take a broader sampling to determine the extent of the issue? (Hint: More than ONE example means it is organizational.)

- ■ How can you fix this problem? Is it your procedure? Is it your training program? Does your training even cover this topic?

Now that you have gathered this information, act on it. Discuss your findings with your team. These are FACTS. You’re not looking for or making excuses. You found a problem, and the team must find a solution. Once you have decided on a solution, implement it—teamwide. Unless you determined that a person was not performing to standard BY CHOICE, assume that everyone is making the same mistake. Do not delay implementation. Problems do not improve with the passage of time.

When you discover a problem, expand your validation to similar topics to see if they are affected by the same type of problem. This is often referred to as “bounding the problem” and is absolutely necessary to an effective self-assessment program. In the case of the oil samples, we would specifically target other daily maintenance items. Oftentimes, this would lead to the discovery of organization-wide issues in training, documentation, and operator performance. Most of the time, the operators were not acting maliciously, they were simply performing the way they were trained by a previous operator.

Lastly, if you found no problems, celebrate that! Find out WHY work is being done correctly. Is the policy well-written and well-received? Is it discussed on a recurring basis? Is it formally taught to new personnel? It is important to highlight the reasons why things are going well, and spread those practices to areas that need improvement.

Using Self-Assessment to Drive Self-Improvement

In order to improve, you must have a starting point. Through the assessment process, you established an expectation, and then determined your reality. Once you find the gap, you can work toward aligning reality with expectations.

Leaders must be mindful that people do not naturally stay good at things unless they practice them. Often, it is the routine, or the “basics,” that fall off the radar and become the genesis of larger problems. By routinely comparing your expectations with reality and correcting small issues, you create the basis for self-improvement. Routinely assessing areas of your operation, particularly vital areas, will help keep the knowledge fresh for you and your team.

Over time, revisit areas that were previous problems, regardless of if the problem has repeated. This will allow you to find trends. Once trends are established, processes can be implemented to correct them before they become larger issues. This process must be repeated to ensure things continue to run smoothly. Each time you repeat this cycle of self-assessment, you improve a new area. Once basic skills are established, advanced skills are worked into the program.

A good rule of thumb for human performance is that we lose knowledge in a subject over the span of about a year. Typically, a quick refresher is all it takes to bump that knowledge back up to a satisfactory level. For infrequent items, “just-in-time” training, training held to refresh everyone’s knowledge just before performing a task, works great. For example, training on freeze protection and cooling tower operations in the late autumn can refresh everyone’s knowledge prior to the winter season. For frequent operations, such as the lubricating oil samples, I found that if it was revisited once a quarter, it drastically reduced the recurrence of problems.

It is worth noting that the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) recognizes this process in some vital areas of safety. Lockout Tagout, Electrical Safety, and Confined Space programs are all examples where OSHA references a “periodic review” of the effectiveness of the program and the conduct of training and/or updating of procedures based on those reviews. To ensure success, apply this mindset to broader areas of your operation.

Constantly Assessing, Constantly Learning

Don’t focus self-assessment only on your organization’s mistakes or shortcomings. Use the failure of others to learn within your organization. If another organization has a problem, look at the causes (Figure 3). Do you have similar processes? Go and look for those similarities in your organization to ensure you aren’t on the same path.

|

|

3. A Baltimore City Fire Department investigation found that a March 2023 explosion at the Back River Wastewater Treatment Facility was caused by dust that ignited in a sewer sludge dryer. Details on catastrophic events such as this can often be found in Occupational Safety and Health Administration or other government agency reports and used for training purposes. Courtesy: Fossil Consulting Services |

In the fire service, we constantly review and discuss other departments’ events, along with our own. What went well? What did NOT go well? What should we change within our own training or policies based on what other groups learned. You would be surprised how often you will find someone else’s mistakes repeated at your facility when you go look for them. The trick is to find them before they find you.

Finally, don’t be bound to one way of doing things. Perhaps your assessment revealed things were not being performed in accordance with the guidance you provided. Why is that? Is your guidance wrong or overly complicated? Perhaps the way it is actually being done is better. If so, incorporate it into new guidance and give credit where credit is due. Things change over time, it is possible that your procedures are written for equipment that is no longer in use, or for which a new standard or better process has been developed. As a leader of an organization, you should constantly be learning and improving too.

—Derek Meier ([email protected]) is a senior training specialist with Fossil Consulting Services Inc. He spent 20 years as an operator in the U.S.Navy Nuclear Power Program, retiring as an operations inspector for Commander, Naval Air Force Atlantic. He is also an active firefighter in North Carolina.