Scarce Projects Raise Red Flag for Skilled Labor

A combination of factors, including a relative scarcity of projects, has cut demand for skilled labor in the power generation sector. Despite the lull, workforce retirements are still expected to challenge the industry.

Like swallows returning to Capistrano or geese flying south in the fall, the cycle of spring and autumn maintenance outages at electric power generating stations is almost a force of nature. Low demand for electricity during shoulder seasons means that units can be shut down for routine repair and upgrades, and then returned to service to meet summer and winter high-demand periods.

For a skilled worker, or for a group that supplies labor for an outage, however, that cycling can be both inefficient and maddening. Inefficient because highly skilled craft laborers are often idle between outages. Maddening because the nature of the power generation business—namely, meeting demand whenever it occurs—suggests there’s no fix in sight.

“A concern for years has been that owners conduct outages at the same time, which puts pressure on the supply of labor,” said Kevin Hilton, CEO of the Ironworker Management Progressive Action Cooperative Trust, which focuses on unionized workforce development. “We have to have a trained and available workforce.” Convincing a young person to train for what ultimately can be a dirty and physically demanding job that is cyclical at best can be a hard sell.

Data show that around 20% of a boilermaker’s total annual labor comes during the first quarter of the year, said Peter Hessler, president of Construction Business Associates. That percentage grows to 35% during the second quarter (coinciding with the spring outage season); drops to 15% in the third quarter, when most power plants are operating to meet summer demand; and recovers to 30% in a typical fourth quarter, as demand eases and autumn outages ramp up. “That’s a heck of a cyclical business that leads some people to wonder why they would want to go into that business,” Hessler said. Over the course of a year, he said, a boilermaker may work only two-thirds of the time on power plant outages.

What’s more, competition for skilled labor is growing, particularly in the Gulf Coast region, where something of an industrial construction boom is under way, spurred by recently plentiful oil and natural gas supplies.

“We are expecting craft shortages to continue to be a strain and actually increase with Gulf Coast refinery work” and related projects, said Jim Breland, vice president of Fluor Power Services. Labor shortages will likely continue during the next five years among tube and pipe welders, millwrights, and electrical expertise.

Melanie Green, a director at CPS Energy in San Antonio, said one of her biggest challenges is to find workers with skills in plant controls. Boom times in the Texas oil patch have made it more difficult for the utility to compete with wages in the oil sector.

Workforce issues in the power generation sector featured prominently as a topic last month during ELECTRIC POWER 2013 in Chicago. Several conference speakers agreed to speak with POWER to extend the discussion beyond the conference. Those interviewed included utility generation asset managers, representatives of organized labor, and professionals like Hessler who help power plants plan for and manage outages.

Concerns over the aging electric power workforce have been expressed for years, and much attention focuses on the industry’s ability to attract well-trained workers as retirements among older, experienced workers progress. Sean McGarvey, president of The Building Trades, said that his labor organization has 1,300 training centers across the U.S. and spends around $1 billion a year on skills training and curriculum development. If his union’s training enrollments were compared to the country’s largest university systems, the craft training network would rank third, he said.

Project Drought?

A more fundamental question for some, however, is whether some utility work is at a low ebb, the result of multiple forces.

For one thing, regulations from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency have led to decisions to close thousands of megawatts of coal-fired generating assets, effectively removing them from future maintenance and upgrade projects. Likewise, recent low natural gas prices have left other generating assets economically uncompetitive and idle, meaning their boilers, generators, pumps, and valves need less regular maintenance. The 2008–2010 recession cut into power demand and led some power generators to defer outages and expansion projects to save money. A related factor is the recent flat trend in wholesale electricity price growth, which has forced many power generators to cut costs, including some maintenance work, to keep their generating assets competitive.

Together, these factors have eroded demand for skilled labor in the power generation sector, said Steve Lindauer, CEO of The Association of Union Construction (TAUC), which has around 40,000 members nationwide, a workforce as large as Microsoft’s.

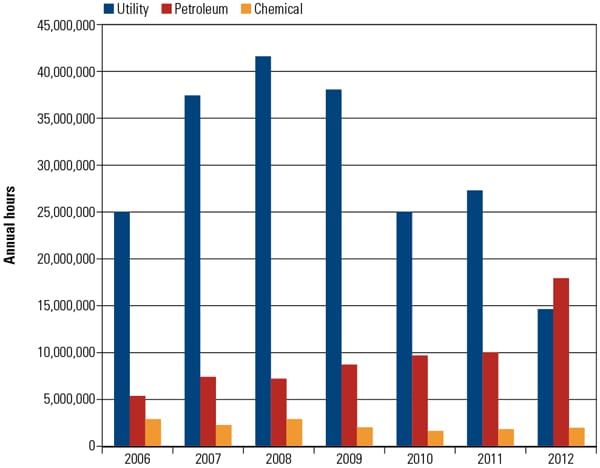

In 2008, more than 40 million work hours for his union members were attributed to electric utility project work, Lindauer said. That added up to around half of all TAUC work hours, which include petroleum, chemical, and several other industries. In 2012, however, work hours related to utility projects fell to fewer than 15 million hours and were eclipsed by work hours in the petroleum sector (Figure 1). “The utility industry doesn’t have a manpower shortage, because the work is drying up,” Lindauer said.

|

| 1. Project scarcity. The number of work hours coming from utility projects has dropped since 2008, the result of many factors that worry groups whose job it is to train a new generation of skilled craft workers. Meanwhile, projects coming from the booming petroleum industry are picking up some of the slack. Source: The Association of Union Construction |

Lindauer’s view was echoed by Gary McKinney, president of Day & Zimmermann NPS, which provides plant maintenance, modification, and construction services to fossil and nuclear power plants across the U.S. As recently as five years ago, his company worried about how to provide enough labor to meet demand for a long list of projects, including an expected surge in nuclear power plant construction. Today, by contrast, the economic downturn has cut into demand growth, lessening the need for new power plants. What’s more, the March 2011 accident at the Fukushima nuclear station in Japan has helped cool talk of a nuclear renaissance. “There are much smaller opportunities today,” McKinney said. With cost cutting top of mind at many power plants, “items that can be moved to a later date are being moved.”

In addition, some power generators have rethought their approach to outages. Many fossil-fired generating asset owners learned lessons from the nuclear generating industry, which made strides in recent decades to reduce the length of planned outages. Whereas 30 years ago a nuclear refueling outage might last 90 days, today’s average is closer to 21 days. Outage planning at a nuclear facility sometimes begins years in advance, a strategy that has helped to add value to practices such as highly detailed scheduling. “There is much more sophistication on the part of fossil owners to plan the work and work the plan,” McKinney said.

Starting around 2001, American Electric Power began a process aimed at increasing its cost competitiveness by looking for ways to stretch the time between outages, said Robert A. Osborne, managing director of Field Services at the utility. Some owners of fossil-fueled assets are diligent about conducting outages every year or 18 months, he said. By contrast, AEP’s outages largely are based on “systemic need,” an approach bolstered by the fact that many of AEP’s generating units are of similar design. This uniformity allows Osborne’s in-house Field Services group to better monitor maintenance trends across the utility’s fleet. The 460 craft personnel under Osborne’s direction handle almost all of AEP’s rotating equipment maintenance work. Other projects are evaluated and taken on only if they add tangible value to the bottom line. If they don’t, then the work may be outsourced to a contractor, Osborne said.

Union or Non-Union?

Management issues don’t end, however, when an outsourcing agreement is signed. One issue is whether to hire a contractor that uses unionized labor or one that does not. Statistically speaking, union membership is declining, Hessler said. “The average guy out of school is not union oriented,” he said. “Why pay dues and get locked into rules?” he asked.

One source said that his experience has been mixed, with some non-union contractors outperforming union contractors doing the same work. In recent years, however, his opinion has changed, especially when it comes to some scaffolding and insulation crews. Here, he said, training and overall professionalism appears better among unionized workers.

Enhancing Productivity

Many factors can negatively affect workforce productivity during an outage, not just training and professional demeanor. Some appear mundane, but taken together they can have a big effect on completing a job on time and on budget.

Those factors include tool crib transactions, morning start meetings, job safety briefings, paperwork, changing dies on pipe-threading machines, crane movements, and waiting for lockout tags on energized equipment, said Charles Vitale, a consultant who spent more than 30 years with a northeastern utility and the last 16 measuring and analyzing outage productivity. In recent years, text messaging during work hours has affected productivity; it proves to be a distraction and therefore poses a significant safety problem, he said.

One major source of lost productivity is the placement of the break station at an outage site. If 250 workers are on the upper level of a power plant and have to go to the ground level for their morning, lunch, and afternoon breaks, a significant hit to productivity can occur. That’s because workers line up for the elevator to descend, and then line up again at the end of the break to return to work. As a result, a scheduled 30-minute break can stretch to 45 minutes or more and add as much as an hour to the workday.

A better approach, Vitale said, is for owners to place a fully stocked break area on the same level as the project itself, if possible. Doing so may reduce the amount of time that is spent waiting for an elevator. With the break area close by, workers simply stop work, walk to the break area, and then walk back to work at the end of the break.

A second step that keeps work crews close to the project site is to shut off the elevators altogether at certain times of the day. “There is no longer a trek, and this is a major step forward,” Vitale said. “It’s no small accomplishment.” As proof, he said that tightening up breaks on one project helped the owner cut what had been a 10-hour work day down to 9 hours. “They no longer were seeing coffee breaks equating with 12% of the work day,” he said. Instead, breaks took up around 8% of the day, lifting productivity and saving money.

Undeserved Breather

A combination of forces has taken some of the edge off the imperative to find a new generation of workers to replace those who are retiring. “You get lulls where outside forces give us an undeserved breather,” said McKinney, noting that the recent recession, among other factors, played a role. Even so, he cautioned that the industry needs to continue paying attention to the workforce issue and looking for creative ways to address it.

For example, efforts are under way to entice a new generation beginning as early as elementary school with programs known as “Crayons to CAD.” Other programs enroll men and women as pipefitter trainees and offer them the equivalent of a two-year degree in construction management as an incentive. Still others look to former members of the armed forces and promote “Helmets to Hardhats” programs in the construction trades.

Despite these initiatives, “more folks are leaving than are available” to take their place, McKinney said. “Decisions that are made today mean the dividends are a few years out. You can’t just flip a switch.”

—David Wagman is executive editor of POWER.

[Note: Name and company spellings corrected 6/5/13.]