PJM: Can the Big Dog Deal with State Interference?

The PJM Interconnection, the largest regional transmission operator in the U.S., faces many problems: adapting to state policies designed to skew power markets in the face of natural gas and renewable generation, the structure of its challenged capacity markets, and how to build a reliable and resilient transmission grid.

The PJM Interconnection, celebrating its 90th anniversary this year, has an enormous footprint in the U.S. East and Midwest. According to its website, the regional transmission operator “coordinates the movement of wholesale electricity in all or parts of Delaware, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Maryland, Michigan, New Jersey, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia and the District of Columbia.”

Over the years, in various incarnations, PJM has faced repeated generation transitions, including the current conventional transitions to natural gas and renewable generation, challenges facing much of the U.S. electricity business. But PJM also is dealing with a revanchist movement in several states with economically uncompetitive legacy generation, particularly nuclear. The states view these large, largely baseload resources as important employers and prolific taxpayers, so they are seeking ways to help them compete in PJM’s auctions.

In a POWER interview, PJM CEO Andrew Ott (Figure 1) said his group is trying “to find a way to harmonize” its competitive markets with state actions to preserve in-state generation. “The challenge has been generation subsidies, which create problems, as costs shift from one state to another.”

The PJM Interconnection in June issued a statement that nicely summarizes the generation issues it now faces. The position paper said, “Since the inception of competitive wholesale electricity markets, the industry has evolved significantly and in ways that could not have been fully anticipated. Technological disruptions—in particular hydraulic fracturing to access vast natural gas reserves; environmental regulation; highly efficient lighting, appliances and industrial processes; and increasing penetration of renewable, distributed and demand response resources—have altered the economics of electricity supply, creating new opportunities and challenges.”

The statement reflects the situation in much of the U.S. electricity market, but really hits home in PJM as its wholesale markets have developed after the 1990s deregulation of formerly monopolistic power markets.

The PJM document notes: “Demands on electricity markets also are evolving. Increasingly, public policies seek to recognize value associated with generation plants beyond their cost effectiveness and reliability attributes.” The challenge of state actions to put a policy thumb on the competitive markets also has shown up in the New York Independent System Operator, where Gov. Andrew Cuomo has rescued upstate nuclear plants that threatened to close when they could not compete against low-cost, gas-fueled generators. ISO-New England has faced the same conundrum but to a lesser degree, mainly related to state subsidies for renewable energy resources.

Nuclear Challenge

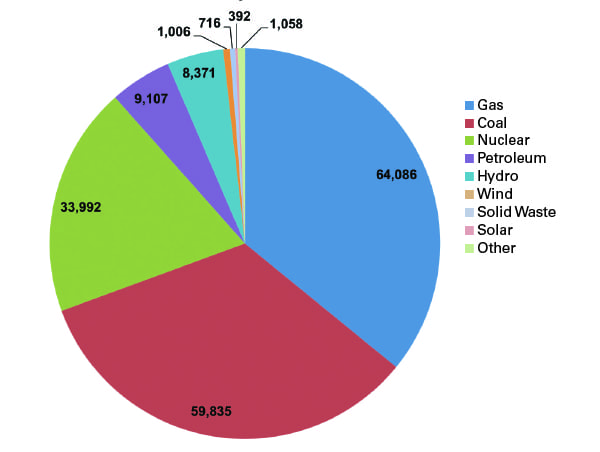

The nuclear challenge is greatest in PJM. Nuclear made up more than 34 GW of the total 94 GW of generation in the PJM system in early September. Coal followed at 28 GW, with gas at 25 GW, and a mix of renewables making up the rest of the total generation. Total generating capacity on the PJM system is about 178.5 GW (Figure 2), with the system serving 65 million people with more than 82,000 miles of transmission lines.

Chicago-based Exelon is the dominant nuclear generator bidding into the PJM market. The company has six of its 14 nuclear stations (Clinton, Limerick, Oyster Creek, Peach Bottom, Quad Cities, and Three Mile Island) in the PJM system. The Clinton and Quad Cities units already benefit from a 2016 Illinois law that awards the plants “zero emissions credits” (ZECs) based on the fact that they do not emit CO2 emissions, and based on a political decision of what those emission reductions are worth.

FirstEnergy, based in Akron, Ohio, also has troubled nuclear units that bid into PJM’s markets: Davis-Besse and Perry in Ohio, and the two-unit Beaver Valley station in western Pennsylvania. FirstEnergy last spring failed to persuade Ohio’s government to create a ZEC program similar to that of Illinois for Davis-Besse and Perry.

PJM in April joined a suit in federal court brought by non-utility generator trade group Electric Power Supply Association challenging the Illinois legislation. The groups argued that a recent U.S. Supreme Court decision (Hughes v. Talen Energy Marketing) made it clear that such state actions violated the Federal Power Act, granting the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission sole authority over wholesale power rates. A district court judge dismissed the suit in July, saying the action was within the state’s authority. The decision is on appeal.

In August, PJM’s independent market monitor, Monitoring Analytics LLC, issued a report for the first six months of 2017. The report found “The PJM markets work. The PJM markets bring customers the benefits of competitive markets.” The analysis added, “Subsidies are tempting because they maintain existing resources and provide increased revenues to asset owners in uncertain markets. Cost of service regulation is tempting because cost of service regulation incorporates integrated resource planning and because guaranteed rates of return and fixed prices may look attractive to asset owners in uncertain markets.”

Looking at Illinois and New York, the monitor’s report commented, “The market paradigm and the quasi-market paradigm are mutually exclusive. Once the decision is made that market outcomes must be fundamentally modified, it will be virtually impossible to return to markets.”

Issues with Subsidies

The subsidy issue came to a head in PJM’s May capacity auction for the 2020–2021 period. Two Exelon plants—Three Mile Island (TMI), located near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, and Quad Cities in Cordova, Illinois—failed to clear the PJM auction. According to Exelon, the single-unit, 837-MW TMI plant has not been profitable in five years, and failed to clear the past three PJM auctions. Exelon said that TMI “remains economically challenged as a result of continued low wholesale power prices and the lack of federal or Pennsylvania energy policies that value zero-emissions nuclear energy.”

Utility Dive commented, “Prices in the PJM Interconnection’s capacity auction were once again disappointing for many generators, but for operators of nuclear power plants they could be a turning point in the evolution of PJM’s market structure as they underscore the competing forces that are coming to a head in the wholesale market.” Exelon announced that it would shut TMI “on or about September 30, 2019,” and take a $110 million write-off this year.

PJM in June rolled out working papers addressing the roiled markets, describing “straw proposals to spur discussion on the interaction of state actions to promote generation meeting environmental, social and/or political interests beyond simply ensuring resource adequacy at the lowest cost and the operation of the wholesale electricity markets.”

Two weeks later, the RTO unveiled its “Capacity Market Repricing Proposal,” which it described as an accommodation of its capacity market to deal with state subsidy programs. It consists of a two-stage auction somewhat similar to what ISO-New England has offered. The PJM plan updates an earlier proposal from summer 2016.

“In this design,” says the PJM paper, “resources would submit one set of offers into a single capacity auction, as they do today. However, the cleared capacity commitments and the clearing prices would be determined in separate stages. Subsidies that are determined to be actionable by PJM and stakeholders would trigger repricing … Resources with actionable subsidies that clear the first stage of the auction would be relied on as capacity resources as they are today and subject to the same reliability obligations. Capacity market offers of subsidized resources will be administratively adjusted in the second, price-setting stage of the auction to prevent distortion of the capacity price.”

“The current proposal,” Ott said, “would allow subsidized resources to count as capacity and carry a load obligation.” But PJM would adjust the price in order to protect the competitive, unsubsidized generation.

A PJM capacity task force met several times over the summer to hash out details of the two-stage proposal. In September, RTO Insider reported that, based on those meetings, “PJM appears headed toward implementing a capacity construct that would reprice auction results to address the influence of subsidized generation offers.” Repricing won support from five of nine proposals. Among the stakeholders backing repricing, in addition to PJM, were NRG Energy, LS Power, Exelon, and Old Dominion Electric Cooperative.

PJM’s Multiple Transitions

In 1927, three utilities—Public Service Electric and Gas in New Jersey (PSE&G), Philadelphia Electric Co. (PECO), and Pennsylvania Power & Light (PP&L)—formed a power pool to offer economic dispatch for the three companies, assuring dispatch of the lowest-cost generating resources first. It was the world’s first continuing power pool, according to PJM. They called the organization the “Pennsylvania-New Jersey Interconnection.” At that time, the dominant generating technology was coal.

In 1956, General Public Utilities in New Jersey and Pennsylvania (GPU), and Baltimore Gas and Electric (BG&E) joined, and the power pool was renamed the “Pennsylvania-New Jersey-Maryland Interconnection,” or PJM. Potomac Electric Power Co. joined in 1965. During those years, the “tight” pool was working on computer-driven approaches to dispatch and began its initial energy management system in 1968.

During the 1970s, the PJM Interconnection began seeing its generation profile change from coal-domination to a heavy participation by nuclear power. PSE&G, PECO, PP&L, BG&E, and GPU were bringing large, baseload nuclear plants on line and into the economic dispatch model.

In 1981, Atlantic City Electric in New Jersey and Delmarva Power & Light in Maryland and Delaware signed onto the PJM system. In 1993, the pool became the PJM Interconnection Association, establishing itself operationally as a largely self-standing organization.

That came as major restructuring was sweeping the electricity business, with policy pushes to break down the vertically integrated electric utility model. That came to a head in 1997, when a series of Federal Energy Regulatory Commission orders (880, 888, and 889) adopted the competitive wholesale market model and approved PJM as the nation’s first independent system operator, and PJM administered its first bid-based power auction.

PJM’s footprint continued to expand, with New York’s Rockland Electric and Pennsylvania’s Allegheny Power joining the system in 2002, and PJM became a FERC-designated “regional transmission organization (RTO),” which is barely distinguishable from an “independent system operator.” Two years later, Ohio-based giant generator American Electric Power, along with Commonwealth Edison in Illinois, and Ohio’s Dayton Power & Light joined the PJM RTO. Pittsburgh-based Duquesne Light and Virginia’s Dominion became PJM members in 2005.

PJM’s footprint grew larger and deeper from 2011 through 2013, when FirstEnergy’s transmission subsidiary American Transmission Systems and Cleveland Public Power turned over control to PJM, followed by North Carolina’s Duke Energy and East Kentucky Power Cooperative. That’s where the mammoth PJM market stands today (Figure 3), after the fracking revolution transformed wholesale markets away from conventional baseload generation and toward gas-fired capacity and renewables (with hefty tax subsidies from federal and often state-sponsored policies).

Transmission Upgrades

In addition to its shorter-term market auctions, PJM uses a 15-year planning process for transmission system upgrades. PJM’s Ott has said that “preserving reliability and the value of PJM’s independent assessment of transmission needs [is PJM’s] fundamental mission.” According to PJM, the RTO’s board has approved $31.2 billion in transmission upgrades and new capacity since 2010. Most of those projects have price tags of less than $5 billion. In July, the PJM board approved $417 million in transmission projects to aid reliability, Utility Dive reported. That includes a new New Jersey substation to support critical infrastructure—health care, government, education, and transportation—in Newark.

Building high-voltage transmission across multi-state jurisdictions has long been a daunting and politically fraught task. Congress attempted to address that by giving the federal government backstop to approve interstate transmission projects blocked by state actions if they were determined to be in the national interest. That approach has not worked.

FERC in 2011 adopted Order No. 1000, calling for broad, regional transmission planning and cost allocation. In written testimony this summer for a House energy subcommittee, PJM’s Washington lobbyist Craig Glazer said, “PJM believes that Order No. 1000 has helped to advance certain aspects of grid planning and infrastructure development but has fallen short in other areas.” The order has been positive in pushing for competitive bids for transmission upgrades. Glazer said PJM received “over 100 proposals under our first ‘market efficiency’ solicitation pursuant to Order No. 1000 when, in contrast, it received very few such proposals” before the FERC order.

But when it comes to interregional transmission planning, Glazer said, the track record “has been far more mixed.” He wrote, “given Order 1000’s embrace of ‘bottom-up’ planning and maintenance of regional differences in the determination of benefits, we believe a metric which looks for the development of major interregional transmission projects covering hundreds of miles may be unrealistic and an inappropriate metric of success.”

| PJM Ponders Grid Resilience and Info Warfare

For the PJM Interconnection, the nation’s largest regional transmission organization, grid reliability is job one. But PJM is also looking beyond reliability to resilience. PJM CEO Andrew Ott said, “Resilience goes beyond existing reliability criteria. While we plan and operate the grid to operate reliably—it’s our first priority—the new charge for us and the industry is making sure the grid stands up to and recovers from a wider range of threats.” Those threats include physical and natural events such as storms, including solar storms, electromagnetic pulse attacks, and cybersecurity threats, all leading to long-duration grid outages with potentially catastrophic consequences. These threats exist in a world of new challenges to fuel diversity. In September, PJM convened its second forum on grid resilience, in Baltimore, featuring an array of government, industry, and other experts on the topic. The September event was a follow-up to an April “Grid 20/20” meeting focused on a report, “PJM’s Evolving Resource Mix and System Reliability.” That report said, “The paper’s focus is on the reliability aspects of fuel mix diversity, including fuel security. The paper offers insight, from a grid operator’s perspective, for policymakers to consider when assessing the impacts of a changing resource mix and poses questions about new impacts to evaluate.” At the Baltimore meeting, Ott stressed that addressing grid resilience was not a matter of “gold-plating” the grid, but taking prudent and often inexpensive steps to plan for threats. “Resilience and reliability are related but resilience goes beyond” conventional reliability criteria. He said PJM’s thinking about resilience involves three elements: examining the criticality of infrastructure components; looking at fuel security and planning for fuel supply disruptions; and planning for system restoration, including black-start plans. Paul Stockton of the security consulting firm Sonecon, and a former assistant secretary of defense in the Obama administration, issued a “call to arms” for the electricity industry to focus on outside attempts to attack the grid. “Let’s get ready for information warfare,” he said. He singled out Russia and China as the adversaries most likely to try to disrupt U.S. infrastructure. “Knowing a cyberattack is on the way is much more difficult” than dealing with natural disasters such as hurricanes, he said. Stockton also advised the utility executives to take a lead role in resilience planning. Should a cyberattack occur, he noted, the federal government has vast authority to step into grid operations. So industry should “anticipate deep government involvement in grid management in the event of an attack.” That means it is wise to start working with the Department of Energy ahead of time to plan federal orders and develop templates to guide the government should attacks occur. |

PJM’s Future Challenges

As PJM’s Ott looks ahead, he sees two challenges facing the utility business in general and PJM specifically. The first, he said, is a policy issue. Current competitive market structures do not value environmental attributes, specifically the value of carbon dioxide emissions reductions. He advocates carbon pricing as a better solution than how PJM and other RTOs are trying to cope with the issue. Ott said “groups of states” could get together and agree on a carbon pricing scheme.

The other issue is squarely in PJM’s back yard: pricing load following. “The energy prices we have been seeing don’t value load following as the supply curve has flattened out,” he said. “Fewer generators are willing to provide flexibility service. The supply curve is so flat, there is not much incentive to be flexible.”

The current supply curve is the result of two phenomena: cheap shale gas and the rise of highly efficient natural gas combined cycle generation. As a result, over the past 11 years, PJM has seen wholesale power prices reduced by 3%. At the same time, nuclear costs are going up, largely the result of fixes ordered after the Fukushima disaster, while coal costs are increasing as a result of environmental regulations. “We are not paying for part of our services. Is this sustainable?” Ott asked. “With a large percentage of the generating fleet on the point of bankruptcy, something’s got to change.”

“Fast forward 10 years,” Ott told POWER, “and we may look back with regret. We have retired large zero-emissions resources. Should we have been pricing in that attribute? Now is the time to answer that question. It’s a public policy issue, not for PJM to solve.”

When it comes to a mechanism to pay for load following, “we don’t have to overreact. Paying for load following is not a big change. The good news could be coming from other, non-generation technologies.” Development of utility-scale battery technology could open up a new route to load following. Competition, he said, “breeds innovation.”

“My job,” said Ott, “is to look further out” than today, and work on the issues of emissions pricing and pricing load following, another coming generation transition that will face PJM. ■

—Kennedy Maize is a long-time energy journalist and frequent contributor to POWER.