How Did MATS Affect U.S. Coal Generation?

Industry aggressively fought the Mercury and Air Toxics Standards (MATS) when the Obama administration proposed it in 2011 and finalized it in February 2012, warning it would precipitate the closure of a swathe of coal capacity nationwide. Six years later, the rule appears to have had a sizable impact on the power sector, but not nearly to the extent its opponents projected.

The rule imposes first-of-their-kind emissions limits for mercury, arsenic, and heavy metals associated with fuel combustion on power plants larger than 25 MW, and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) says it affects about 600 power plants, which include 1,100 existing coal-fired units and 300 oil-fired units. The EPA received close to a million public comments on the MATS proposal alone—substantially more than any prior rule-making—and most comments from industry decried its potentially exorbitant costs associated with compliance and its potential threat to energy reliability.

An Environmental Success

When the EPA published its final MATS rule in February 2012, it released a companion regulatory impact analysis that projected annual incremental private costs of the final MATS to the power sector would be $9.6 billion in 2015 (in 2007 dollars). But it also estimated that the annual benefits of the rule, including the avoidance of up to 11,000 premature deaths annually, would be between $37 billion and $90 billion.

Although the Trump administration’s EPA last week sent proposed changes to the rule’s approach to weighing costs and benefits to the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB), the agency told POWER on October 2 that it backs the rule’s aim to protect health associated with the continued reduction of mercury.

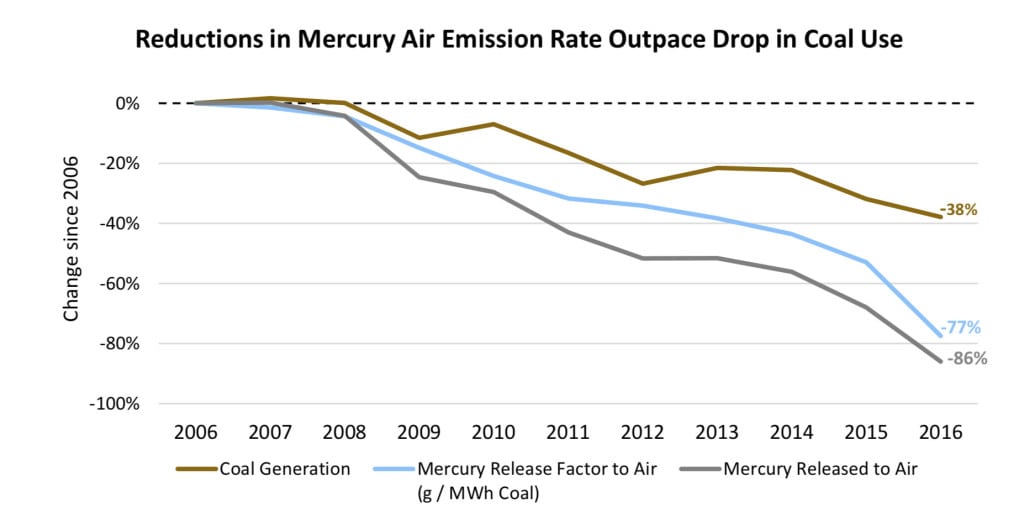

The environmental benefits of the rule are tangible, it said. In a January 2018 report summarizing analysis of its 2016 Toxics Release Inventory, the EPA noted that since 2006, net electricity generation from coal decreased 38%, while the rate of release of mercury to air per GWh of electricity from coal dropped 77%. In 2016, three times more mercury in coal ash was disposed of on land compared to air-released mercury—a stunning turnaround, considering that in 2006, the amount of mercury disposed on land was less than half that released to air, the agency noted. Electric utilities overall reduced their mercury air emissions 85% (80,000 pounds) between 2006 and 2016. Total mercury emissions, including air releases and land disposal from the sector fell 48% (68,000 pounds) since 2006.

Source: EPA 2016 Toxics Release Inventory

Source: EPA 2016 Toxics Release Inventory

Costs for Compliance

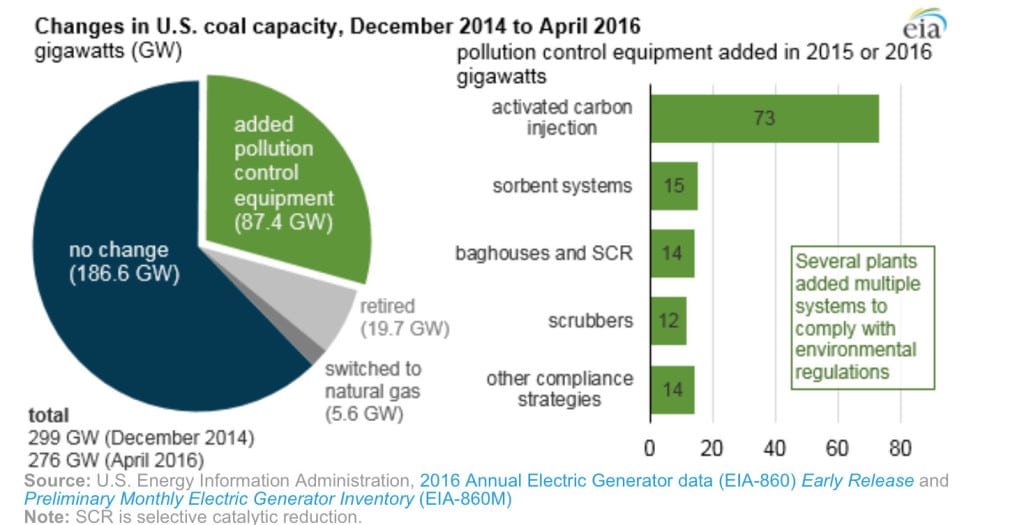

What MATS cost the industry is less clear. According to the Energy Information Administration (EIA), between January 2015 and the rule’s April 2016 compliance deadline, 87 GW of coal-fired plants installed pollution control equipment, and 20 GW retired (but 186.6 GW of the then 276-GW national coal fleet had reported no changes—and it is unclear if these units shut down or are factored into planned retirements). About 26% of the 20 GW of retirements during those two years occurred by April 2015, presumably to meet the rule’s initial compliance date.

Between 2014 and 2016, power generators invested an estimated $6.1 billion to comply with MATS or other environmental regulations, according to the National Coal Council (NCC). By 2016, more than 73 GW of coal capacity was outfitted with activated carbon injection, effectively doubling the amount of coal capacity with ACI. A number of facilities also implemented a combination of control technology such as flue gas desulfurization scrubber systems, selective catalytic reduction systems, and fuel additives.

Source: EIA, September 2017

However, when several prominent power trade groups sent a letter to the EPA this July urging the agency to “leave the underlying MATS rule in place and effective,” they estimated that owners and operators of coal- and oil-based electric generating units have spent more than $18 billion to comply with the rule since it became effective in 2012. The groups noted that all covered plants had implemented MATS and pollution controls were installed and operating. The $18 billion estimate was “in addition to these operating costs,” they said, noting that “states are relying on the operation of these controls for their air quality plans.”

The Reliability Question

When MATS was first proposed, it set off a firestorm about its effect on reliability. In 2011, the North American Electric Reliability Corp. concluded that between 32.6 GW and 53.6 GW of capacity will retire by 2018 as a result of the EPA’s July 2011–finalized Cross-State Air Pollution Rule and proposed MATS. The DOE, which commissioned an independent study on grid reliability in 2011, projected that about 29 GW of coal capacity would shut down as a result of the two rules, but it concluded the closures would not cause reliability challenges. In a 2012 report titled “EPA’s Utility MACT: Will the Lights Go Out?” the Congressional Research Service also agreed it was unlikely that electric reliability would be harmed by the rule, but it projected only 4.7 GW would be retired or derated.

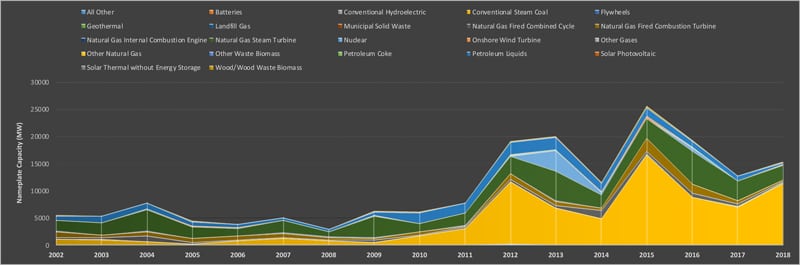

At the end of 2017, coal-fired capacity stood at 260 GW, down from a peak of 310 GW in 2011—a 50-GW decline—and the EIA projects, based on announced retirements, that another 25 GW will retire within the next three years. In its Annual Energy Outlook 2018 reference case, EIA projects that coal capacity could decline 65 GW between 2018 and 2030, with total installed capacity leveling off near 190 GW through 2050.

Significantly, however, while experts largely agree that regulatory considerations hastened coal plant closures, they underscore that the coal power industry’s current woes are rooted in a long-standing struggle to compete in a changing market.

In a draft report published this September (and approved by its membership on October 3), the NCC, a 35-year-old nonprofit that serves as an advisory group to the U.S. Energy Secretary, lamented the retirement of 24% of coal capacity between 2005 and 2017, and noted that nearly 40% of the U.S. coal fleet operating in 2010 has retired, converted to another fuel, or is slated for retirement by 2030. But NCC fashions its strategic objectives and tactics to stem the decline of coal power around an assortment of factors that caused it, notably: “competitive pricing from other fuel resources, federal and state energy and environmental policies, declining electricity demand, inadequate funding for technology innovation, and societal pressures.”

Existing and proposed environmental rules with compliance deadlines between 2010 and 2017 factored into retirement decisions for coal units that “were already economically marginalized due to the competition from low natural gas prices and mandated deployment of renewable technologies,” the NCC noted in the report, which is titled, “Power Reset: Optimizing the Existing U.S. Coal Fleet to Ensure a Reliable and Resilient Power Grid.” Citing data from the American Coalition for Clean Coal Electricity—a coal power lobby whose president has also noted coal retirements were for “good reason”—the NCC estimated that of more than 115 GW of retired, converting, or planned retirements, nearly 77 GW “are explicitly attributed to U.S. [EPA] existing and proposed regulations/policies (from 2010–2030).”

“One of the most significant triggers for coal generating unit retirements,” the NCC said, is the new economics associated with natural gas. “A price of $4/MMBtu will cause [combustion turbine] and [natural gas combined cycle] to be dispatched ahead of some subcritical and older coal-fired units,” it noted. Subsidies, mandates, and other policies for renewables, including the production tax credit and investment tax credit, have also reduced market prices for non-subsidized fuels, it noted.

[For more on gas plant costs, see “Natural Gas and Wind Dominate U.S. LCOE Landscape, Interactive Map Shows” in this week’s POWERnews issue]

The Impact of Regulatory Uncertainty

The final MATS may have triggered the “greatest number of retirements in one year,” the NCC acknowledged, but the industry also faced regulatory uncertainty associated with the now-defunct Clean Power Plan. “Regulatory uncertainty in general, may also have impacted consideration of investments in new and existing coal plants as there is little certainty that investments will get a fair opportunity to be earned back,” it said. “There is an argument to be made that environmentally permitted investments should be given the opportunity to earn their value over their useful life or just compensation should be due if that opportunity is denied.”

The impact MATS had on the coal industry has, meanwhile, become a specific rallying cry for the Trump administration. In the spring of 2017, the DOE issued two emergency orders to keep open four coal units otherwise slated for closure due to MATS (at a plant in Oklahoma and another in Virginia). And last September, the DOE proposed a “Grid Resiliency Pricing Rule,” directing the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) to require that grid operators establish reasonable rates for power plants that show “reliability and resiliency attributes.” .

FERC slapped down the measure in January, but a memo leaked this June shows the Trump administration is mulling preventing “the further permanent loss of the fuel-secure electric generation capacity,” for national security reasons. That memo cites figures from the EIA’s 2015 Annual Energy Outlook when it suggests that “by 2025, coal plant retirements related to [MATS] could increase annual electricity costs by 50% and raise peak costs by 81%.”

While no new developments have been made public concerning the memo, or its measures to rescue beleaguered coal plants, the NCC on October 3 announced that its members (who serve in a voluntary capacity) endorsed creating a DOE-led government-wide task force to monitor and coordinate policy developments relevant to advancing coal exports.

Among core recommendations to achieve that objective are to deploy advanced coal mining and processing technologies to reduce production costs, thus making U.S. coals more competitive in international markets, and to enhance U.S. coal mining operations with export potential in both traditional and non-traditional coal supply regions. The NCC also calls for enhancements for river and land transport infrastructure, and a general federal push to improve trade opportunities abroad, such aspromoting “the elimination of regulatory and institutional barriers to the deployment of coal-based facilities worldwide.”

The NCC’s statement more briefly noted that NCC members also approved the “Power Reset: Optimizing the Existing U.S. Coal Fleet to Ensure a Reliable and Resilient Power Grid,” report, which essentially focused on domestic power production from domestically produced coal. Key strategic objectives of that approach include an assessment of the value of the current coal fleet; supporting efforts to retain continued operation of the existing fleet; reforming the regulatory environment; and renewing investment in coal generation through research development, demonstration and deployment.

NCC CEO Janet Gellici told POWER on October 4 that the “Power Reset” report will be forwarded to Energy Secretary Rick Perry “in a couple of weeks with NCC’s recommendations.”

—Sonal Patel is a POWER associate editor (@sonalcpatel, @POWERmagazine)