China’s Shanghai Institute of Applied Physics (SINAP) in November reported it had achieved thorium-to-uranium fuel conversion inside an operating molten salt reactor (MSR). The milestone provides the first experimental data from thorium fuel loading in a liquid-fuel MSR and advances validation of the thorium-uranium fuel cycle, the institute said.

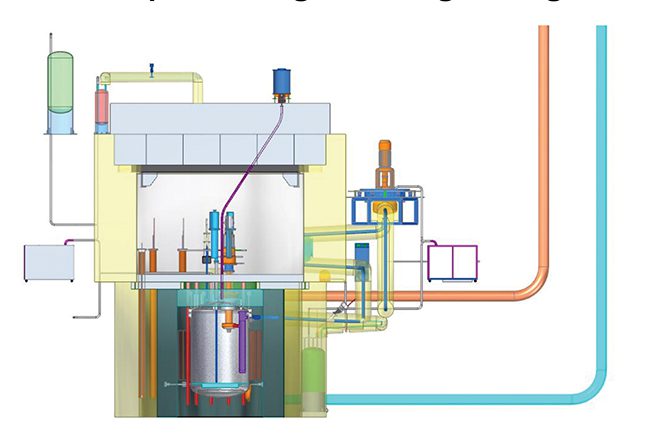

SINAP, a leading Chinese national nuclear research institute operating under the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), said the milestone was achieved at the 2-MWth thermal experimental thorium molten salt reactor (TMSR-LF1) in Wuwei, Gansu Province, a facility built by SINAP in collaboration with other Chinese institutions. While the institute has not released detailed technical data about the conversion process, according to CAS, the experimental TMSR “is currently the only operational molten-salt reactor in the world loaded with thorium fuel” and has “obtained valid experimental data following thorium fuel loading,” confirming “the technical feasibility of thorium utilization in a molten-salt reactor nuclear energy system.”

A Decade-Long State Commitment

The TMSR-LF1’s development reflects a decade-long state commitment to thorium-MSR technology. CAS launched its Strategic Priority Research Program on “Future Advanced Nuclear Fission Energy—Thorium-based Molten Salt Reactor Nuclear Energy System” in 2011, seeking to advance national security and sustainability goals while building a specialized research and development (R&D) team focused on thorium-based molten salt technology. Nearly 100 domestic research institutes, universities, and industrial groups participated in the reactor’s design, materials development, equipment fabrication, installation, commissioning, and safety validation, it says. The institute reports a localization rate exceeding 90%, noting that “key core equipment is 100% localized” and the supply chain is “independent and controllable.”

|

|

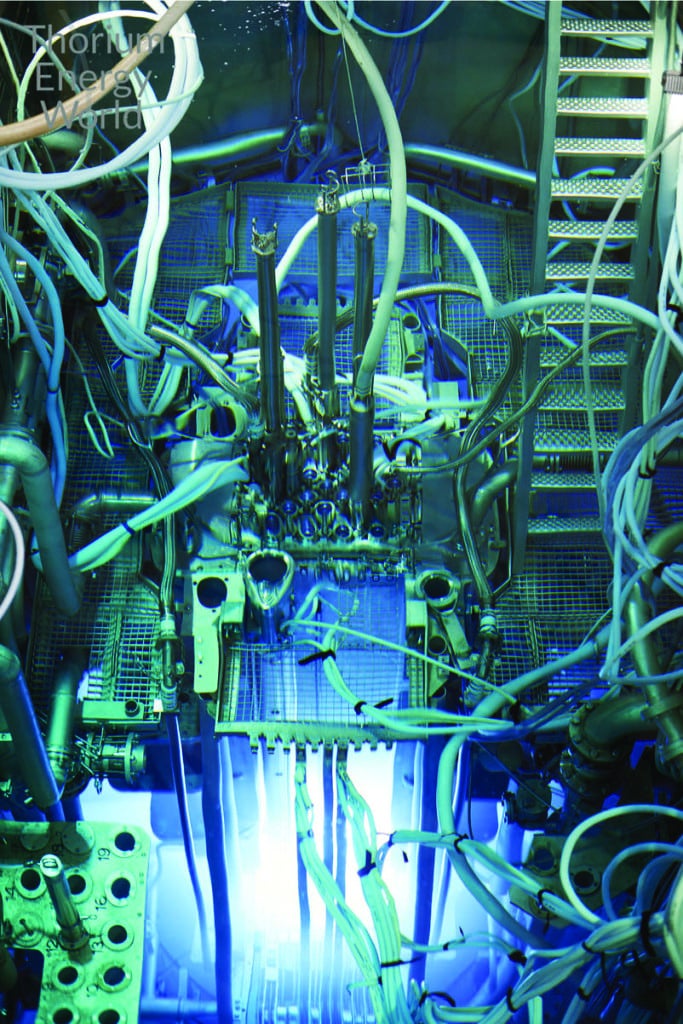

3. Thorium Molten Salt Experimental Reactor (TMSR-LF1) main vessel being lifted into position at the Wuwei site. Courtesy: Shanghai Institute of Applied Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences |

Construction of TMSR-LF1 began in September 2018 (Figure 3). According to SINAP, the institute completed “the world’s first thorium addition to a molten salt reactor” in October 2024, establishing what it describes as a thorium-uranium fuel-cycle research platform within an operating liquid-fuel MSR. The reactor achieved first criticality on October 11, 2023, under an operating license issued in June 2023, and reportedly reached full operation in June 2024.

The development has drawn close interest, given the longstanding but largely unrealized potential of thorium (Th-232) as a nuclear fuel precursor, and particularly because the element is both abundant and attractive for multiple fuel-cycle concepts. According to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), thorium is widely distributed with an average concentration of 10 ppm in earth’s crust and is almost three times more abundant in nature than uranium. Thorium’s allure also stems from its physical and neutronic characteristics, which the IAEA notes “may be exploited in current and next generation nuclear energy systems” for goals such as improved conversion performance, enhanced inherent safety, and reduced minor-actinide production.

However, because thorium is fertile rather than fissile, on its own it cannot sustain a chain reaction. In any practical thorium system, Th-232 must absorb a neutron to become Th-233, decay to protactinium-233, and then decay again to a fissile uranium isotope capable of sustaining fission. That sequence only proceeds if a fissile “driver” such as uranium-235 or plutonium-239 is already present to supply both the power and the surplus neutrons required for breeding. Thorium’s contribution, therefore, typically hinges on how efficiently a reactor can convert neutrons absorbed in the blanket or salt into usable uranium fuel rather than losing them to leakage or parasitic absorption, a constraint that has limited past thorium-fuel experiments, the IAEA notes.

R&D into thorium fuel cycles continues globally, particularly in countries with abundant thorium reserves and active nuclear programs. India, notably, has pursued thorium utilization as a cornerstone of its three-stage nuclear energy strategy, given its large thorium reserves and limited uranium resources. Canada, Germany, the UK, the U.S., Norway, and Japan have also explored thorium fuel cycles since the 1960s, including conducting test irradiations in heavy-water reactors, high-temperature gas reactors, and molten-salt systems. Recent activity points to even more momentum for thorium fuels.

The Promise of Thorium

While India’s Department of Atomic Energy has moved to intensify its thorium-based fuel research, in the U.S., backed by the Department of Energy, Clean Core Thorium Energy achieved a historic burnup milestone with its ANEEL thorium fuel at Idaho National Laboratory (the company also notably secured an export license to deploy thorium fuel in India and signed a cost-share project with Canadian Nuclear Laboratories to validate thorium-based fuel technology under the Canadian Nuclear Research Initiative).

In Denmark, Copenhagen Atomics is developing 100-MWth thorium molten salt reactors targeting first commercial deployment by 2030, with the company claiming raw fuel costs of $2.22 USD/GWh—orders of magnitude below conventional solid-fuel reactors—and plans for future breeder reactors designed to consume spent nuclear fuel. Thorizon, a Dutch–French MSR startup, is working to develop Thorizon One, an advanced small modular MSR that uses long-lived nuclear waste as fuel—recently garnering significant European backing through the EU’s Just Transition Fund and a €20 million Series A round to advance prototyping, licensing, and design work as it targets first construction around 2030, according to the company.

And in Indonesia, ThorCon International achieved regulatory approval in August 2025 from regulatory agency BAPETEN for its ThorCon 500 molten salt reactor—a 500-MWe dual-module plant comprising two low-enriched-uranium-fueled 250-MWe reactors—on Kelasa Island, marking the first-ever nuclear power plant licensing decision from the Indonesian government and targeting construction in 2027 and full power by 2031 to support Indonesia’s 10-GWe nuclear capacity goal by 2040.

As experts note, however, despite accelerating global interest, thorium reactor deployment faces several significant economic and technical hurdles. For one, thorium extraction costs have historically remained high because it is primarily a byproduct of rare-earth element mining, typically recovered from monazite deposits, a mineral containing rare-earth elements. While mining companies extract monazite for its rare-earth content, thorium is often removed as a low-value byproduct. A second challenge is that thorium reactor R&D is also relatively capital-intensive, owing to an absence of commercial operational experience and established fuel cycle infrastructure, at least compared to uranium’s century-long development pathway. Then, thorium can be difficult to handle, given it is a fertile material and needs a driver, such as uranium or plutonium, to trigger and maintain a chain reaction. And finally, regulatory frameworks for thorium fuel cycles remain underdeveloped worldwide, and a lack of established thorium fuel-fabrication and quality-assurance supply chains could add further cost and uncertainty for developers.

Some thorium experts, however, argue that thorium’s nascent status positions it as a strategic opportunity, particularly for energy security, industrial decarbonization, and future reactor intellectual property leadership. In the U.S.—and notably in light of SINAP’s milestone—firms such as Thorium Atomics, developer of the Tesseract (a 75–150 MWe modular gas-cooled reactor using TRISO fuel with thorium), are rallying support behind the Thorium Energy Accelerator Project (TEAP), a proposal now circulating in Washington, D.C. The TEAP document contends that the U.S. must act within the next two to three years to avoid a permanent technological disadvantage relative to China, warning that the nation risks losing leadership in molten-salt chemistry, thorium fuel-cycle science, and next-generation reactor intellectual property. It calls for $500 million to $1 billion in federal action to address market failures and regulatory barriers—particularly the complete absence of a domestic thorium fuel supply chain and supporting fuel-cycle infrastructure.

|

|

|

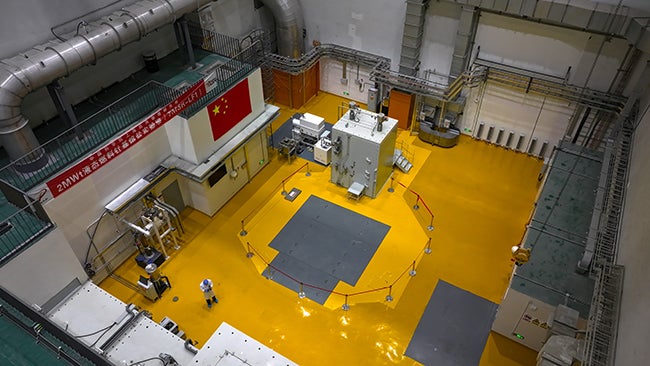

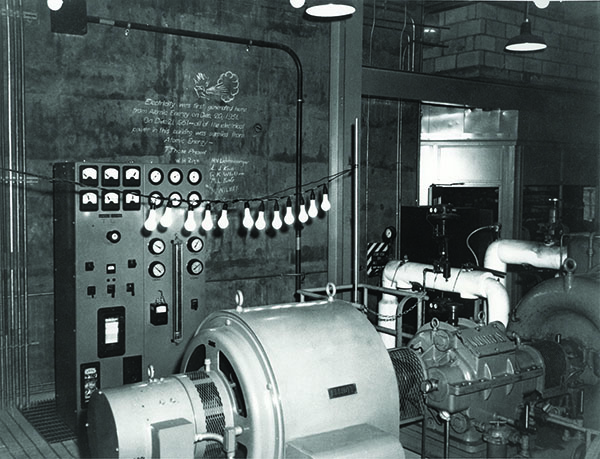

4. The main hall of the 2-MWth Thorium Molten Salt Reactor (TMSR-LF1) experimental facility in Wuwei, Gansu Province. The reactor achieved first criticality in October 2023 and began full operation in June 2024. Courtesy: Shanghai Institute of Applied Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences |

China’s Three-Step Pathway

For now, China’s TMSR-LF1 remains the only operating reactor demonstrating continuous thorium-uranium conversion under real irradiation conditions (Figure 4). According to Chinese publication ThinkChina—though unverified by POWER—China’s plans will reportedly follow a three-step development pathway. After running the 2-MWth experimental reactor, which has now achieved thorium-to-uranium conversion, to gather key data, the second step involves building a 10-MW small modular demonstration reactor by 2029 to verify commercial viability and establish core infrastructure supply chain capabilities. The third step targets construction of 100-MW power stations by 2035, enabling large-scale application in thorium-rich regions such as Gansu and Xinjiang while spurring development of equipment manufacturing, molten salt materials, and related industrial clusters. CAS has said SINAP will work with leading energy companies to consolidate the TMSR industrial and supply chains and “accelerate technology iteration and engineering application.”

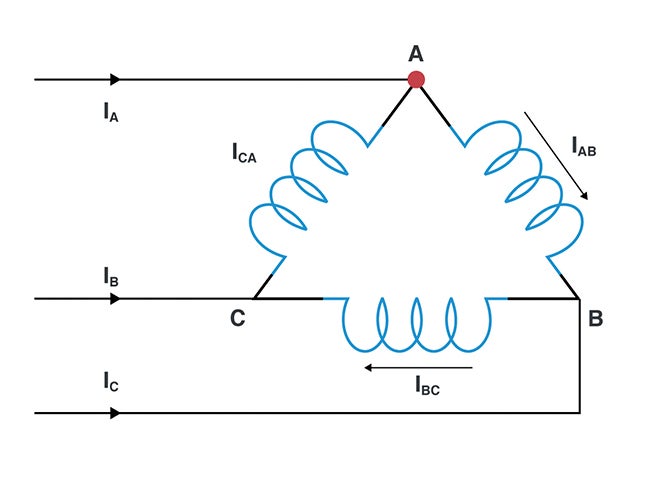

For China, MSRs represent a particularly promising platform for thorium fuel utilization. MSRs, fourth-generation advanced nuclear energy systems that use high-temperature molten salt as a coolant, “possess inherent advantages such as safety, waterless cooling, atmospheric pressure operation, and high-temperature output,” making them “internationally recognized as the most suitable reactor type for the nuclear energy utilization of thorium resources,” CAS says.

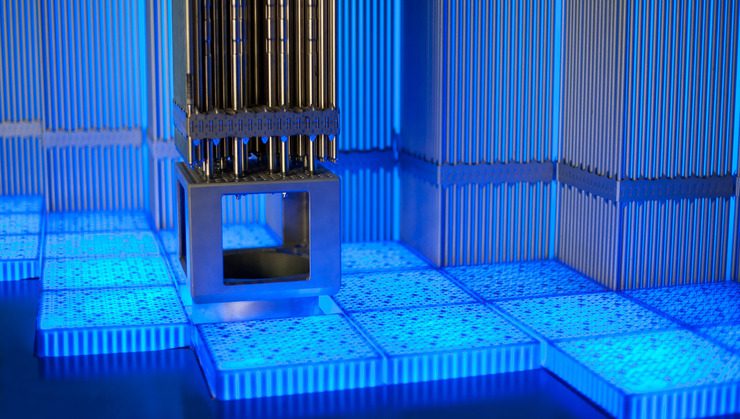

In TMSR-LF1, the fuel is dissolved directly into the circulating molten fluoride salt, which functions simultaneously as coolant and carrier. In principle, the liquid-fuel configuration enables continuous salt circulation, online refueling, and on-stream management of fission products without the periodic shutdowns required for refueling solid-fuel pressurized water reactors, a capability CAS has highlighted as central to validating thorium-uranium conversion in a molten-salt environment.

MSRs, meanwhile, have a lengthy history, stemming from Oak Ridge National Laboratory’s Molten Salt Reactor Experiment (MSRE), which ran from 1965 to 1969, demonstrating the feasibility of liquid fluoride salt fuel systems at temperatures of 600–700C and ambient pressure. The technological route “aligns particularly well with China’s abundant thorium resources” and enables “deep integration with industries such as solar power, wind power, high-temperature molten salt energy storage, high-temperature hydrogen production, coal chemical engineering, and petrochemical engineering, facilitating the construction of a complementary, low-carbon, integrated energy system,” CAS says.

—Sonal Patel is a POWER senior editor (@sonalcpatel, @POWERmagazine).