The last operating reactor at France’s oldest nuclear power plant is scheduled to shut down June 30, some 43 years after the plant entered commercial operation. The French government, though, on June 27 ruled out further full closures of nuclear plants, according to Reuters, which cited sources in the country’s energy ministry.

France had said it would close several of the country’s operating reactors by 2035, as it looks to reduce its reliance on nuclear power, and under pressure from neighboring countries including Germany and Switzerland. The Reuters’ report could mean the country is re-evaluating that strategy.

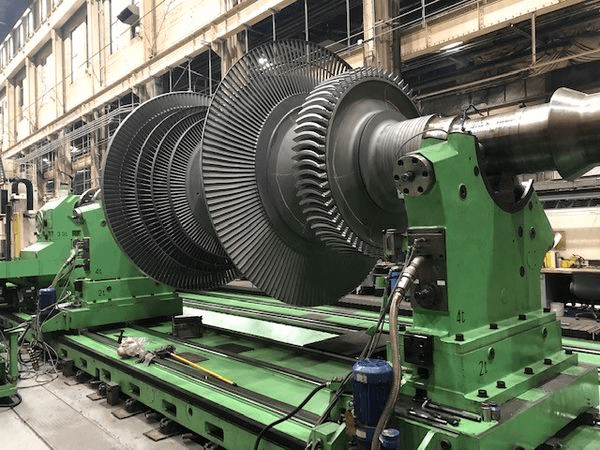

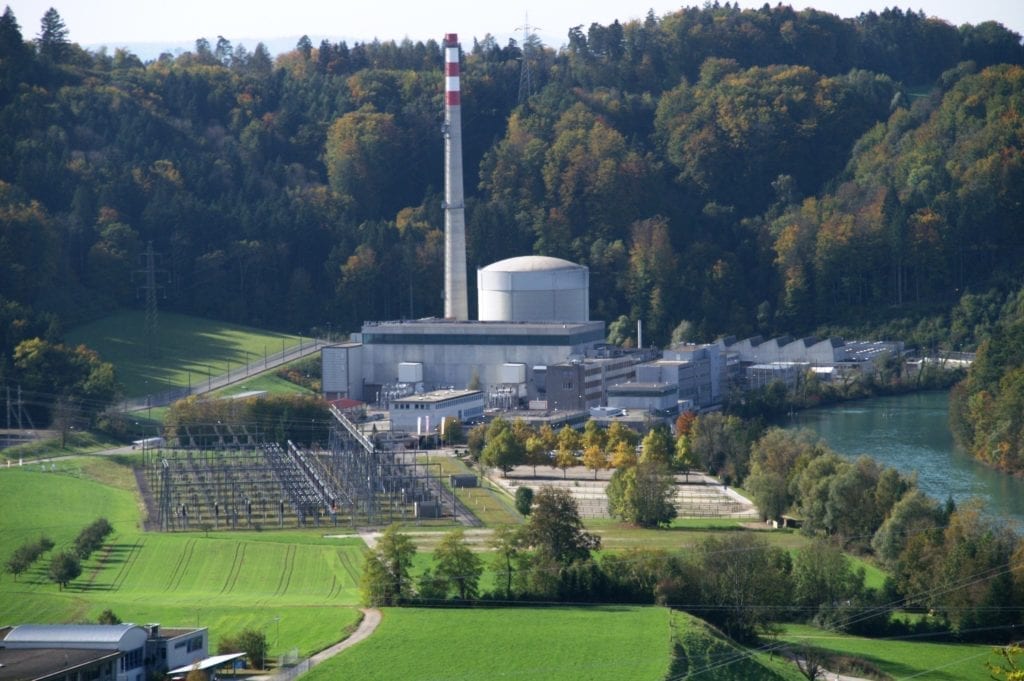

The Fessenheim Nuclear Power Plant, located in eastern France on the border with Germany, opened in 1977. The 880-MW plant, run by state-owned energy company EDF, took its other 880-MW pressurized water reactor offline in February, days after the government announced it would shut down both of the facility’s reactors.

Maintenance Issues, Protests

The plant, like some other reactors in France and elsewhere, was plagued by maintenance issues. Several safety-related issues were reported at the plant over the past several years, including non-lethal radioactive contamination of workers. Other problems included an electrical fault, cracks in a reactor cover, a chemistry error, water pollution, and a fuel leak.

A 2007 study by Switzerland found that seismic risks in the Alsace region had been underestimated during construction of Fessenheim. ASN, the French Nuclear Safety Authority, cited a “lack of rigour,” or strict adherence to regulations, in EDF’s operation of the plant.

Fessenheim operated for three years beyond its expected 40-year life span. The plant was the subject of numerous protests from environmental activists. Anti-nuclear groups called for the plant, and others in France, to be closed after the Fukushima incident in Japan in 2011.

Anne Laszlo, union representative for workers at the plant, in a statement said, “We hope, above all, to be the last victims of this witch hunt against nuclear” energy.

Local officials have been vocal in their opposition to the plant’s closure, citing economic concerns since much of the region’s economy is tied to the nuclear plant. French media have cited data that says about 2,200 jobs have been directly or indirectly tied to the nuclear plant. Claude Brender, a local mayor who opposed the plant’s closure, said Fessenheim had helped create an “island of prosperity” in an economically challenged part of the Alsace region.

An engineer at the plant, Jean-Christophe Rouaud, who already has found work at another nuclear plant, told Agence France-Presse that Fessenheim employees have been “afraid to no longer hear the machines running.” He said there was a “sense of waste shared by all employees.”

Germany, Switzerland Called for Plant’s Closure

Officials in Germany, which receives imports of power from Fessenheim, also called for the plant’s closure after that country made the decision to close all its nuclear power plants following Fukushima. Neighboring Switzerland also called for the plant to be closed, citing a risk from earthquakes in the region. Fessenheim is located about 25 miles from the Swiss border.

Then-French President Francois Hollande had pledged to close Fessenheim just months after Fukushima, but it was not until 2018 that Hollande’s successor, current president Emmanuel Macron, gave the go-ahead for the plant’s shutdown.

France receives about 75% of its electricity from nuclear power, according to the World Nuclear Association (WNA), and is the world’s largest exporter of electricity due to its low cost of generation. The French government, which according to the WNA receives more than €3 billion per year (about $3.4 billion) from power exports, has said it wants to reduce its reliance on nuclear power to 50% of the country’s generation by 2035.

The WNA said the shutdown of the last reactor of Fessenheim will leave France with 56 operating reactors, with about 62 GW of generation capacity. The government had planned to close at least a dozen more reactors, all near or exceeding 40 years of service, in the next 15 years, though Friday’s report could mean officials will alter that plan.

New Reactors Under Construction

EDF, even as some reactors are taken offline, is building new reactors. The company a few years ago had said it could close Fessenheim once operation of a new-generation European pressurized reactor (EPR) was assured at the Flamanville site in France. EDF in early June said an inspection of safety valves at Flamanville 3 would not cause further delays to the plant’s startup, now expected in 2023. Commercial operation of Flamanville 3—construction on the plant began in 2007, and it was expected online in 2012—has been delayed for several years due to equipment issues and repair work during construction.

EDF has said the removal of spent fuel from the Fessenheim reactors should be completed by 2023, though decommissioning and demolition of the plant could take 20 years or longer. Fessenheim at the end of 2017 had more than 1,000 workers on site, but officials have said they will need just 294 on site during fuel removal, and just 60 workers will be needed to demolish the plant.

EDF signed a protocol agreement with the French government before it submitted its decommissioning application for Fessenheim, and the state will compensate EDF for taking the plant offline. The initial fixed portion of those charges, which are expected to total about €400 million ($433 million), will cover the anticipated costs associated with Fessenheim’s closure. Those costs include retraining staff, decommissioning the plant, the basic nuclear facility tax, and post-operational costs.

RTE, the country’s national grid operator, earlier this year said it did not expect Fessenheim’s closure to impact the security of France’s electricity supply, even with the delay in bringing the Flamanville plant online.

—Darrell Proctor is associate editor for POWER (@DarrellProctor1, @POWERmagazine).