While the wind sector battles bearing failures and blade damage, a quieter revolution is unfolding at the heart of the nacelle. Fibre optic rotary joints are replacing electrical slip rings, promising to eliminate one of wind power’s most persistent maintenance nightmares.

The global wind industry is fiercely battling reliability issues to keep wind turbines turning. From bearings and blades to much smaller, yet critical components, original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) struggle to contain reliability issues that threaten both turbine performance and technology credibility, and I’ve seen firsthand how even small components can trigger outsized challenges.

Amid this turmoil, one of the industry’s most critical yet often overlooked components is also facing increased pressure: the electrical slip ring. A component I’ve worked closely with for many years, electrical slip rings have long been the workhorse at the centre of a wind turbine nacelle, enabling data and power transfer across rotating interfaces. However, they’re now being pushed to higher limits—with evolving performance expectations in harsher and more remote environments with the need for greater reliability over the whole lifetime of the product.

As the sector battles to increase uptime and extend platform lifetimes beyond the original life expectancy, the industry can simply no longer ignore the limitations of this technology on legacy and new product alike. Fibre Optic Rotary Joints (FORJ, Figure 1) offer a way out. These precision components, which allow light signals to pass seamlessly between stationary and rotating interfaces, are already transforming radar, defence, and marine systems as well as emerging as a decisive innovation for wind power. Offering high-speed, interference-free data transfer and zero maintenance over lifetimes that outlast the turbine itself, these comparatively smaller parts are primed to bolster the wind sector. OEMs and operators are often trapped in cycles of short-term fixes, could FORJs represent a genuine shift toward a truly future-focused communication infrastructure?

|

|

1. Fibre Optic Rotary Joints (FORJs) for wind turbine applications are precision engineered for uninterrupted turbine communications. Courtesy: BGB |

A Crisis of Reliability

Wind’s reliability challenge is not confined to blades or bearings. Communications failures—intermittent data loss, electromagnetic interference (EMI)-induced glitches, and sensor dropouts—can cascade through turbine control systems, undermining predictive maintenance and reducing energy yield. Electrical slip rings, which rely on physical contact between brushes and rings, are particularly prone to degradation.

In many designs, these components must operate continuously through extreme temperature shifts, humidity, and vibrations. Over time, brush dust contamination, grease, oils, oxidation, and mechanical wear cause noise or shorting between channels, which degrades the communication signals. Service intervals shrink to months rather than years, and should unexplained communication issues be observed, the owner operator is forced to restart the turbine as though it is a slow running personal computer. If this doesn’t work, increasingly rare and in-demand turbine service technicians are drafted in. If the turbine is offshore, this could be costing tens of thousands a day.

This issue has increasingly become more acute as turbines have grown more intelligent. Modern platforms process enormous data volumes from sensors embedded across blades, hubs, and nacelles. Systems monitoring pitch load, torque, temperature, and vibration rely on clean, high-speed, and secure communication between stationary and rotating sections. But as data demands scale, slip rings that were previously adequate for Mbps signals a decade ago, now choke at rates approaching and exceeding 100 Mbps. Electrical noise and impedance mismatches introduce data corruption that no amount of “turn it off and on again” can resolve.

In this scenario, the cost implications are severe. According to the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI), unplanned maintenance costs account for approximately 50% of total wind turbine operations and maintenance (O&M) expenses, equating to about $7.5 billion annually in the U.S. alone. The industry’s margin for technical underperformance has never been smaller.

A Data-Driven Future Demands More

The decarbonisation race has turned wind into one of the most data-intensive forms of generation. More sensors are being integrated into modern turbines, driving growth in data flow across rotating interfaces. These streams are the foundation for health monitoring and life-extension analytics, but their accuracy depends entirely on transmission quality.

At the same time, many turbines in operation today are entering middle age with a real burst in installation rates between 2005 and 2012 leading to a large fleet of ageing turbines approaching end of normal service life. As operating environments become increasingly demanding, the focus is shifting toward technologies that can enhance performance and extend the lifespan of existing assets, ensuring they continue to deliver efficiently and reliably for years to come.

Lightning remains a formidable hazard, bringing current discharge events capable of disrupting conductive pathways—as seen in wind farms where strikes can damage turbine electronics or bring operations to a halt. With the right safeguarding, such as Lightning Protection Systems (LPS), these risks can be effectively mitigated, helping to protect assets and maintain reliable performance even under severe weather conditions.

Even with effective safeguards in place, certain components remain exposed to transient surges. Electrical slip rings, by design, naturally provide a pathway for, or can be susceptible to, these currents.

The problem is amplified offshore or in coastal locations, where the exposure rate to lightning events is so much higher than in-land. The International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) notes that isolated structures have lightning stroke densities three to five times higher than urban building clusters. In this landscape, the industry’s growing dependence on electrical pathways for data looks increasingly untenable. A technology immune to EMI, lightning-induced surges, and contact wear is essential. That technology is fibre optics.

What Makes FORJs Different

An FORJ replaces electrical conduction with light transmission, maintaining continuous optical connectivity between rotary and stationary fibres. This simple shift from electrons to photons eliminates the two biggest failure modes in conventional slip rings—mechanical wear and EMI. FORJs transmit pure optical signals through precision-aligned lenses or prisms, maintaining consistent signal strength and fidelity even as the joint rotates millions of times.

Technically speaking, the advantages are profound. High-bandwidth data rates are now achievable, allowing gigabit-class performance for sensors, cameras, and control systems embedded in rotating assemblies.

FORJ also offers remarkable resilience to environmental challenges. These components are immune to lightning-induced interferences and vibrations, and their non-contact design eliminates the dust and debris issues common with their electrical counterparts. For operators, these features directly translate into reduced maintenance costs and far fewer unscheduled maintenance-related shutdowns—critical factors when downtime is simply not an option.

A Market in Transition

While the concept of optical communication in rotating systems is not new, 2024 and 2025 have marked a turning point for commercial adoption. Market research by DataHorizzon in 2024 projected that the global FORJ sector will grow from roughly $725 million to nearly $1.9 billion by 2033—a compound growth rate of greater than 9%. The anticipated acceleration is largely driven by energy and defence applications, where both uptime and data integrity are mission-critical, but also in wind, where these applications are emerging as the next major frontier.

This momentum is reshaping decision-making within OEMs. For years, the perceived risks of integrating FORJs—higher initial costs, unfamiliar optical interfaces, and certification uncertainties—outweighed the benefits. But that calculus is changing.

For manufacturers, like ourselves at BGB, the pressure to design for longevity rather than patch over weaknesses is intensifying, and FORJ aligns perfectly with this pivot. Now, more than ever, we’re placing huge amounts of focus on removing maintenance dependency, stabilising data throughput, and immunising one of the most failure-prone links in the turbine ecosystem.

Beyond the cost of inaction, that can quickly equate to tens of millions in avoidable losses in replacement parts and downtime, the reputational stakes are rising. Reliability is now the key differentiator in OEM tenders, particularly as government-backed projects prioritise proven lifetime performance. Failures linked to electrical noise or data dropout are increasingly visible to operators through digital twin analytics and diagnostics—and in our highly connected world, where performance and missteps can be shared instantly via social media and online platforms, shifting to an optical architecture is not simply a technical upgrade, but a strategic investment in brand resilience.

Integration and Future-Readiness

The scalability of optical communications future-proof wind designs for decades to come. As turbines incorporate blade-mounted LiDAR (light detection and ranging), high-resolution imaging, and advanced structural sensing, data volumes will surge.

While electrical pathways will struggle to keep pace, optical fibre can scale effortlessly through wavelength multiplexing or channel expansion. The same fibre infrastructure can support tomorrow’s 40-Gbps telemetry just as easily as today’s 1-Gbps systems.

Equally important in today’s security conscious landscape, optical systems are inherently secure. Unlike electrical signals, they emit no electromagnetic signature, reducing the risk of interception or cross-talk. In an era where cybersecurity is a growing concern even for industrial assets, this advantage is significant.

Toward an Optical-First Era in Wind

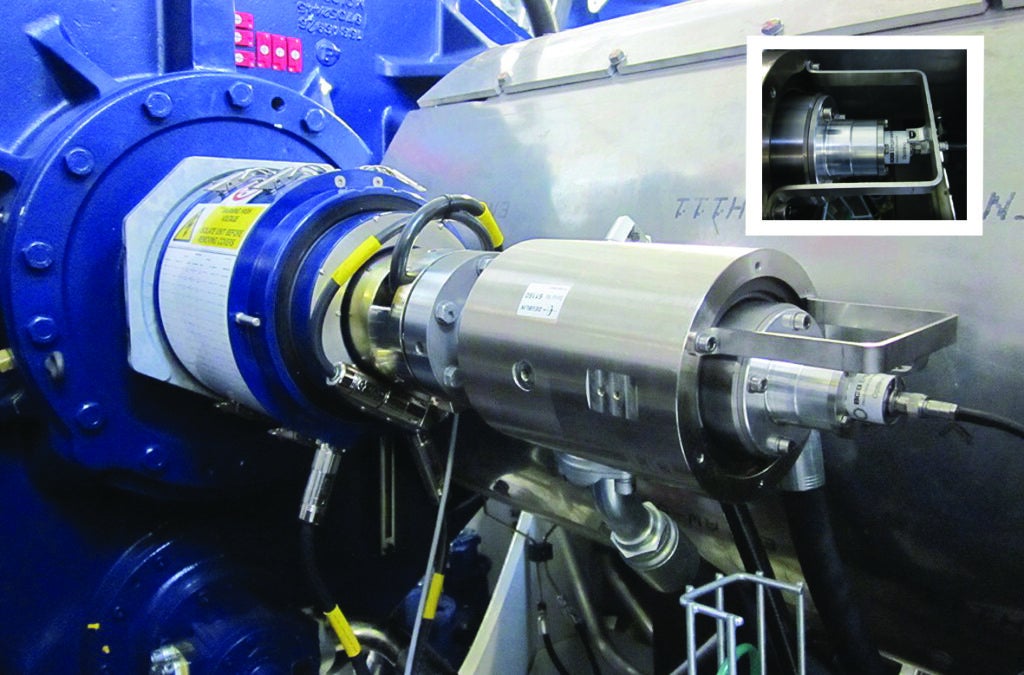

This shift from electrical to optical communication in turbines mirrors broader industrial trends. In aerospace, FORJs are already displacing traditional slip rings (Figure 2) in gimbal systems and satellite ground stations. In medical imaging, they power high-resolution rotary scanners where zero data loss is mandatory. The same logic now applies to wind.

|

|

2. Slip rings enable power and data transfer in rotating systems like wind turbines, but can be—without regular maintenance and high-quality materials—at risk of contact wear damage. FORJs use light instead of physical contact, eliminating maintenance issues. Courtesy: BGB |

Turbines are effectively massive, rotating sensor platforms operating under extreme environmental stress. Their success depends on the integrity of the data they generate, and that integrity begins at the communications interface.

For OEMs, adopting FORJs represents more than solving a maintenance headache. It’s an opportunity to redesign for reliability, efficiency, and scalability. Optical systems remove a failure vector, extend service intervals, and enable richer data architecture that supports artificial intelligence (AI)-driven monitoring and lifetime optimisation. As turbines evolve toward greater complexity, FORJs will become as essential as the blades themselves.

The firefighting phase of wind’s development must give way to foresight. The industry can no longer afford to engineer for five-year service lives when assets are expected to perform for 25. FORJs provide a proven, future-ready alternative—immune to interference, capable of higher data transfer, and built for more than 200 million cycles.

In the race to decarbonise the grid, every revolution counts. Ensuring that data can travel across those revolutions, flawlessly and forever, may be the most important design decision of the next generation of wind technology. For an industry defined by movement, it’s time its communications caught up.

—Ben Murphy is head of product development at BGB.