As the global demand for clean energy intensifies, nuclear power is enjoying a resurgence not seen in decades. However, this renewed interest has exposed a critical vulnerability in the U.S. energy sector: a massive disconnect between uranium consumption and domestic production. As a guest on The POWER Podcast, Thomas Lamb, president and CEO of Myriad Uranium, discussed some of the complexities of the nuclear fuel cycle and how junior exploration companies are racing to secure America’s energy future.

The Great American Supply Deficit

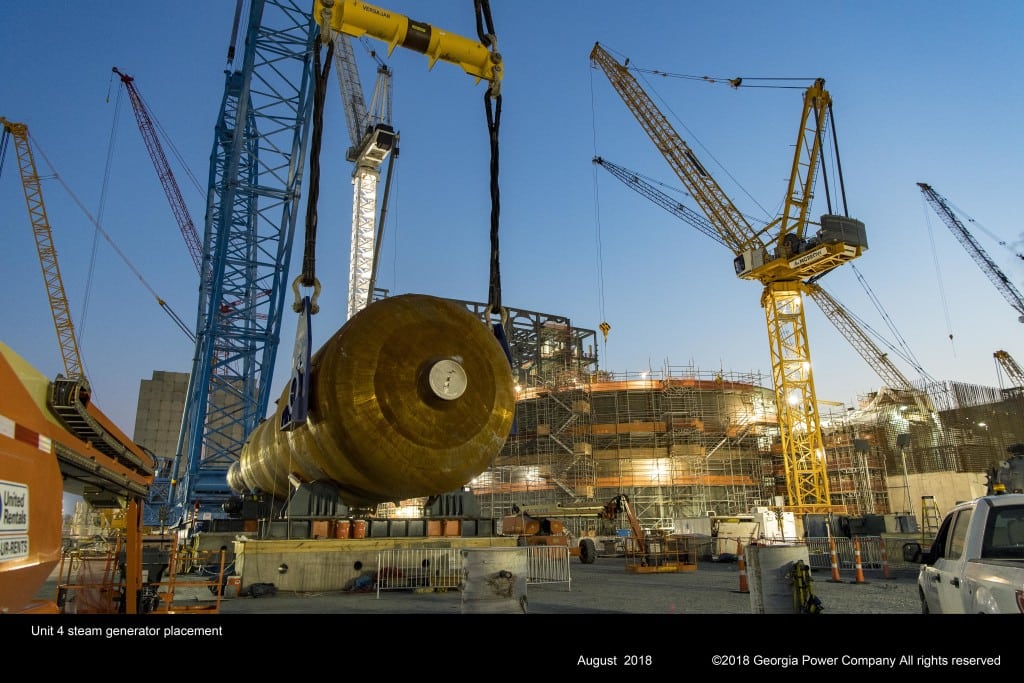

To understand the urgency of the current uranium market, one must first grasp the sheer scale of consumption. A single large-scale nuclear reactor consumes approximately 400,000 to 500,000 pounds of uranium oxide concentrate (U3O8) annually, depending on design, capacity, and operating efficiency. The U.S. operates 94 commercial reactors today, resulting in a national consumption of roughly 37 million to 47 million pounds of U3O8 per year.

The domestic production figures, however, paint a starkly contrasting picture. “The United States consumes, for very round numbers, 50 million pounds of uranium per year, and produces a million pounds of uranium per year,” Lamb explained. To be more specific, the U.S. Energy Information Administration reported that domestic production of U3O8 was 677,000 pounds in 2024, and it’s been much lower than that in the not-too-distant past.

This imbalance creates a precarious reliance on foreign imports. Lamb noted that Kazakhstan alone produces more than 40% of the world’s uranium. More concerning for U.S. national security is the country’s reliance on Russia, where a surprisingly high percentage of U.S. reactor fuel bundles are sourced.

“You have a worldwide supply deficit, and then you have an enormous domestic production deficit in the United States relative to consumption. That makes the U.S. vulnerable,” Lamb said. “What if Kazakhstan, China, [and] Russia kind of work together? What if they cut off the United States? What if some other things happen? The U.S. could be short of uranium.”

Understanding the Fuel Cycle

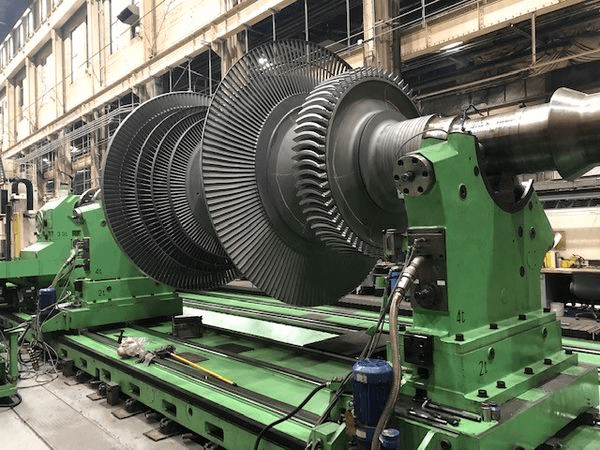

The journey from the ground to a reactor is complex. Uranium naturally occurs as 99.3% uranium-238 (U-238) and only 0.7% uranium-235 (U-235). However, U-235 is the isotope most desired for fission. In most cases today, that 0.7% must be enriched to between 3.5% and 5% to become useable fuel.

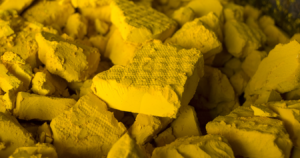

Lamb detailed the extraction methods for uranium, primarily highlighting “in situ recovery.” In this method, operators target roll-front uranium deposits in permeable sandstone. Instead of digging open pits, they drill injection and production wells, circulate a groundwater-based leaching solution (typically with oxygen and carbonate) through the ore zone to dissolve the uranium, then pump the uranium-bearing fluid to the surface, where the uranium is extracted and dried into “yellowcake” (uranium oxide concentrate).

Once mined, the yellowcake faces a bottleneck. It must be converted into a gas called uranium hexafluoride, or “hex,” as Lamb called it, and spun in massive centrifuges to increase the concentration of U-235. Lamb emphasized that while securing raw uranium is getting difficult, acquiring capacity at conversion and enrichment facilities is becoming even harder and more expensive.

Why This Cycle Is Different

The uranium market has historically been defined by extreme volatility. The industry flourished in the U.S. during the Cold War, incentivized by government floor prices, leading to massive overproduction. However, the Three Mile Island accident in 1979 effectively froze the U.S. sector. Subsequent attempts to revive the industry were stymied by the 2011 Fukushima disaster, which caused capital to evaporate and exploration to cease.

This lack of investment has led to the current crisis. “The world produces about 160 million pounds of uranium per year, but consumes 200 million pounds,” Lamb noted. The market has been surviving on stockpiles and under-production for years, but those buffers are gone.

When asked if this is just another boom-and-bust cycle, Lamb argued that the structural fundamentals have shifted. “This time, the market is free,” he said. “The price of uranium trades based on supply and demand factors. And there simply is not enough supply and demand is rising.” Unlike previous cycles driven by artificial government pricing or short-term panic, the current price surge is driven by a genuine, long-term deficit that will take a decade or more to resolve, Lamb suggested.

Revitalizing History: The Copper Mountain Project

Myriad Uranium is positioning itself to fill this gap by revitalizing past assets rather than starting from scratch. The company’s flagship asset, the Copper Mountain Uranium Project in Wyoming, was a focal point of Union Pacific’s energy subsidiary in the 1970s.

Union Pacific invested approximately CA$117 million (in 2024 dollars, US$84.7 million) into the site, planning a large-scale mine to fuel reactors in Southern California that were ultimately never built due to the post-1979 nuclear freeze. Because the project was abandoned due to external market forces rather than a lack of resources, it represents a “brownfield” opportunity.

“In our case, we already know it’s there because a lot of the work was done,” Lamb said. “Now, we just have to … bring the information current,” he added.

A 1982 study by the U.S. Department of Energy assessed the broader assessment area including the Copper Mountain project site as having potentially 655 million pounds of uranium, though Lamb clarified that not all of this is economically mineable. However, Myriad believes the site is “historically under-explored.” Previous operators focused only on the easiest terrain. Today, Myriad utilizes modern drone technology and radiometric studies to map radiation in steeper canyons and hillsides that were previously ignored.

The Business of Exploration and De-Risking

For investors, understanding the business model of a company like Myriad is crucial. Lamb described the company as an “explorer developer.” Myriad claims to operate on a “proof before production” model. The company’s goal is not necessarily to build and operate the mine itself, but to verify the resource, obtain permits, and “de-risk” the asset until it is valuable enough to be sold to a major producer or taken over by a construction-focused management team.

“The actual game here is: you see a project like Copper Mountain … maybe this won’t become a mine for another five to seven years, but they’re going to de-risk this project over the next two years,” Lamb explained. He advised that as the company hits milestones, such as confirming data and securing permits, the share price should reflect that reduced risk, allowing investors to take profits along the way rather than waiting up to a decade for the first pound of yellowcake to be produced.

Government Support and the Path Forward

Concern in Washington about nuclear fuel supply risks has driven a wave of bipartisan support for nuclear energy and the broader fuel cycle. Recent federal legislation under the Biden administration has strengthened incentives for advanced reactors and domestic fuel infrastructure, while the current administration has issued executive actions signaling additional support for expanding U.S. nuclear capacity and fuel supplies. Uranium was recently added to the U.S. critical minerals list, a designation that can improve access to federal financing tools, certain tax incentives, and defense‑related programs that may benefit qualifying uranium mining and processing projects.

Looking ahead, Myriad aims to advance its Copper Mountain and Red Basin (New Mexico) projects significantly over the next 12 to 24 months. The company recently raised CA$8.6 million (US$6.2 million) to fund drilling campaigns aimed at expanding its known resource base.

If successful, Lamb envisions the project eventually producing four to five million pounds of uranium annually—a significant contribution to the U.S. supply chain. While the timeline to production remains several years out, the immediate focus is on proving that American uranium is ready to power the next generation of reactors.

As Washington pushes to rebuild domestic uranium supply and utilities face pressure to diversify away from Russian fuel, companies like Myriad are positioning themselves as the answer. Whether there’s enough capital, time, and uranium in the ground to meet that ambition is the 655-million-pound question.

To hear the full interview with Lamb, which contains more details on Myriad Uranium’s projects and the nuclear fuel cycle in general, listen to The POWER Podcast. Click on the SoundCloud player below to listen in your browser now or use the following links to reach the show page on your favorite podcast platform:

For more power podcasts, visit The POWER Podcast archives.

—Aaron Larson is POWER’s executive editor (@AaronL_Power, @POWERmagazine).