Nuclear power has emerged as a linchpin for U.S. goals for energy and national security. The nuclear sector has a long history of bipartisan support, including through the Advanced Reactor Demonstration Program, the ADVANCE Act, the Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) Loan Programs Office (LPO), and most recently through a series of executive orders (EOs) from the Trump administration. In these orders, the U.S. seeks to revive its historical dominance in nuclear technologies, with critical objectives that include targeting 400 GW of installed capacity by 2050; streamlining permitting and licensing of civilian, military, and experimental reactors; establishing critical supply chains (including the development of spent nuclear fuel reprocessing); and promoting U.S. commercial nuclear innovation and development globally.

Focusing on the civilian commercial nuclear sector, despite strong political support, nuclear deployment in the U.S. is hindered by structural bottlenecks. Only three new units totaling about 3,400 MW have been brought online in the past 25 years. This record highlights the difficulty of accomplishing the goal of constructing an additional 400 GW in the next quarter century.

Permitting, licensing, and construction timelines often extend well beyond a decade. A cornerstone of the recent EOs is the requirement that construction licenses for new reactors be completed in 18 months, and license renewals for existing reactors be completed in 12 months, significantly faster than current approval periods. To support faster reviews, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) has been directed to begin major regulatory updates within nine months and complete them within 18 months, with a mandate to consider the economic and national security aspects of nuclear technology in addition to safety, currently its exclusive licensing mandate. Finally, the orders also direct the NRC to replace the restrictive “zero radiation” siting standard with science-based limits more consistent with policies in Canada and the UK, where radiation limits are set based on risk-informed and site-specific scientific assessments.

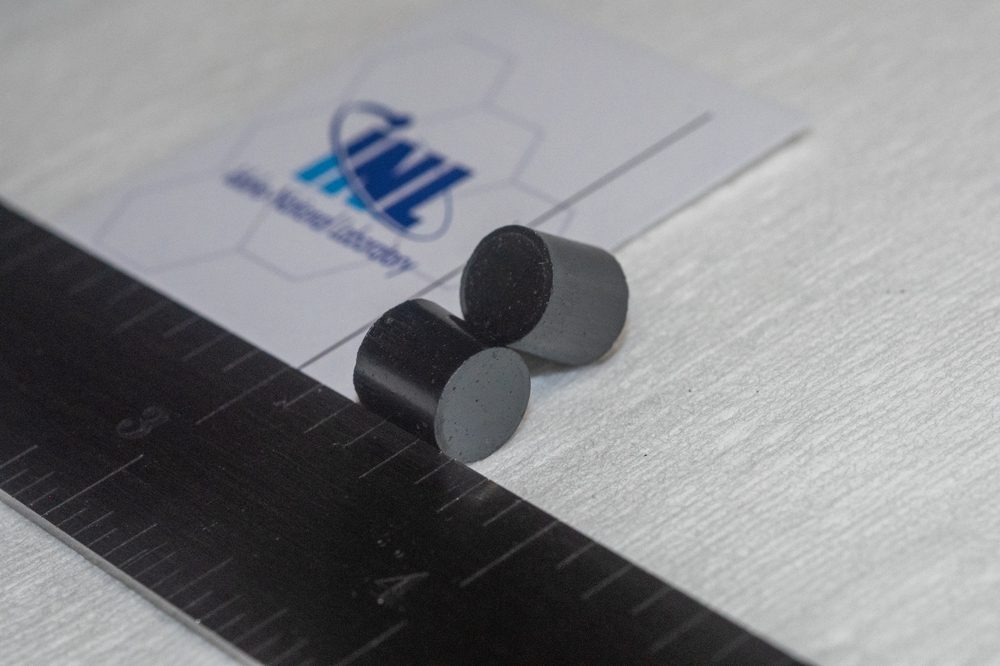

In order to jumpstart attainment of the 400 GW by 2050 goal, the EOs invoke the Defense Production Act and empower the Energy Secretary to coordinate and establish nuclear procurement agreements outside of antitrust regulations. Perhaps the most critical supply chain hurdle to several advanced reactor designs is a lack of high-assay low-enriched uranium (HALEU) fuel, which is currently only commercially available from Russia.

The Biden administration kickstarted domestic production of HALEU, supporting Centrus Energy’s demonstration cascade in October 2023, and through conditional HALEU allocations. The current orders build on this momentum with the additional release of up to 20 metric tons of HALEU fuel for data centers, and the creation of a fuel-purchasing consortium framework for LEU and HALEU, again with antitrust regulation exemptions. To round out the fuel supply chain, the orders have ceased current plans for long-term disposal of spent nuclear fuel, and have opened the door for the development of spent fuel reprocessing technology critical to several advanced reactor manufacturers, such as Oklo, and other advanced designs.

To catalyze innovation, the EOs require the demonstration of three new experimental reactors by July 4, 2026. International peers provide useful context. Russia launched its Akademik Lomonosov floating small modular reactor (SMR) in May 2020; it is now delivering power to Arctic regions. China connected its Generation IV high-temperature gas-cooled modular pebble bed (HTR-PM) reactor to the grid in December 2021, achieving full commercial operation in late 2023. These milestones are rapidly shifting the economics of reactor development, creating a cost curve that the U.S. must match to remain competitive.

On the export front, U.S. SMR developers have signed multiple memorandums of understanding in recent years with countries including Poland, Romania, Canada, and the UK, positioning American technology for a growing global market. Russia’s Rosatom currently has active projects in more than 10 countries. Korea Hydro & Nuclear Power (KHNP) secured an $18 billion contract for new reactors in the Czech Republic. Korea Electric Power Corp. (KEPCO) delivered the Barakah Nuclear Power Plant in the United Arab Emirates, that country’s first nuclear facility.

To increase its global competitiveness, the U.S. is actively strengthening its export network by recently signing new Section 123 agreements with Singapore, Thailand, and the Philippines, and the EOs target an additional 20 countries. The orders have directed the DOE’s LPO under Title 17 to open its portfolio to nuclear projects domestically, and is targeting the start of construction of 10 large reactors by 2030.

The recent EOs reflect a commitment to continuing the revitalization of the U.S. nuclear industry by streamlining licensing processes, strengthening domestic supply chains, and enhancing global competitiveness. We would prefer to see several of the provisions codified in law. In the near term, we expect HALEU shipments to developers, Title 17-backed financing deals, and rapid workforce and supply chain mobilization. Long-term success, however, will depend on delivering streamlined certainty in the licensing and permitting process. The goal of reaching 400 GW of nuclear capacity by 2050 remains within reach, but only with coordinated regulatory, financial, technical, and international trade strategies. If fully codified and implemented, these initiatives could reinvigorate American nuclear energy, positioning it as the backbone of climate-resilient grids, artificial intelligence-driven economies, and U.S. global energy leadership.

—Mike Granowski is partner, Americas Energy Platform Lead, at Roland Berger.