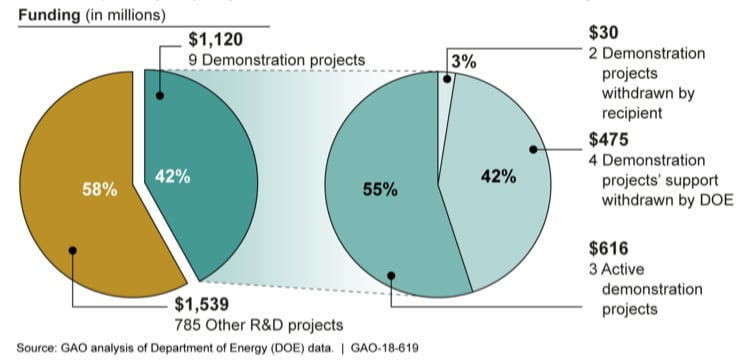

Nearly half of the $2.66 billion spent by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) since 2010 to develop advanced fossil energy technologies was dedicated to nine carbon capture and storage (CCS) demonstration projects—but only three were active at the end of 2017, and only one was at a power plant.

In a report prepared for the Senate Energy and Natural Resources that was released on October 1, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) says that the DOE provided $2.66 billion in funding or obligations to 794 fossil energy research and development (R&D) projects. Of the total $2.66 billion it spent since 2010 (the year that the DOE’s current data management system came into use), about $1.12 billion was provided—in amounts ranging from $13 million to $284 million—to nine “later-stage, large demonstration projects that were to assess the readiness for commercial viability of CCS technologies.” Six of these projects used coal, and the other three used methane, ethanol, and pet coke. Industry paid an additional $610 million in cost-share for these projects, the GAO found.

But out of these nine projects, the DOE withdrew its support for four projects (costing the DOE $475 million):

- Two large demonstrations associated with FutureGen 2.0, which it began in 2011 and scrapped in 2015, after the DOE spent $200 million. “DOE directed the suspension of FutureGen 2.0 project development activities in February 2015 because DOE concluded that there was insufficient time to complete the projects before the closure of the Recovery Act appropriations account on September 30, 2015,” the report notes.

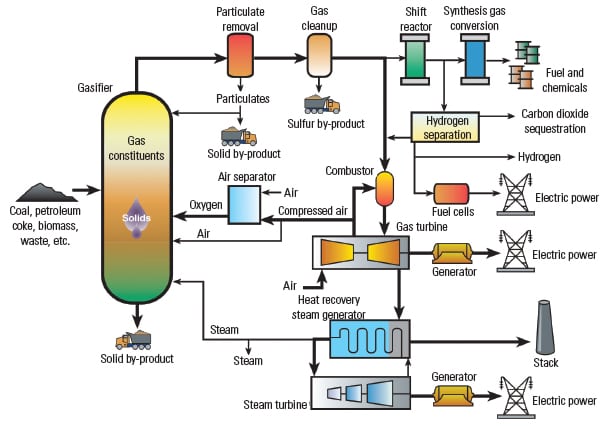

- Hydrogen Energy California, a proposed integrated gasification combined cycle (IGCC) plant and fertilizer plant with CCS, which was abandoned in July 2015, after the DOE spent $154 million. The project faced a number of challenges, “such as obtaining permits, planning a railroad extension, and securing additional financing sources for construction,” DOE officials told the GAO.

- Summit Texas Clean Energy, another IGCC project with CCS in Penwell, Texas, but which was officially dead in 2017, after the withdrew its support, despite $120 million in DOE funding.

The DOE said the project failed to achieve the technical objectives specified under the DOE award and had not secured financing for the project. In 2016, the DOE Office of Inspector General issued a report about its viability, the GAO noted, and a full audit report issued later in 2018 expressed concerns about the DOE’s management of its financial aspects.

Two other projects were withdrawn by the recipient (costing the DOE $30 million):

- American Electric Power’s Mountaineer project to capture CO2 from a coal plant near New Haven, West Virginia. AEP froze the project in 2011 for uncertainty in U.S. climate policy and the weak economy. The DOE provided $17 million.

- Lecadia Energy’s CO2 capture from a pet coke-to-chemicals gasification plant in Lake Charles, Louisiana. The DOE provided $13 million.

The DOE said that these six projects did not reach completion due to several factors, “such as a lack of technical progress, or changes in the relative prices of coal and natural gas that made the projects economically unviable.”

Only three major projects—just one of which was at a power plant—remained active at the end of FY2017 and cost the DOE a combined $615 million:

- Petra Nova (POWER’s 2017 Plant of the Year), a project that began capturing 90% of CO2 emitted from a flue gas stream from NRG Energy’s 3.7-GW W.A. Parish power plant in Texas in November 2016. The DOE, which will be involved in the project until December 2019, provided $190 million between 2010 and 2017. “While the economics of carbon capture and Petra Nova remain challenging, the plant is running as designed and has captured more than two million tons of CO2,” NRG spokesperson David Knox told POWER on October 9.

The project remains only one of two power-related operational CCS projects in the world. The second is Boundary Dam in Canada (POWER’s 2015 Plant of the Year). Southern Co.’s Kemper County, Mississippi, IGCC project would have been the third, but it was scrapped in June 2017 days before it was slated to go in-service after delays prompted cost overruns that put the total project price tag at $7.5 billion. According to the GAO, Kemper’s fate appears expected. “It is not unusual for projects in the demonstration phase of the R&D process to experience higher-than-anticipated costs, delays, and other challenges,” it said.

- Archer Daniels Midland of Illinois, which is demonstrating capture of CO2 as a by-product of fuel-grade ethanol production for sequestration in the Mt. Simon Sandstone formation (a saline reservoir) in Illinois. The DOE provided $141 million and will conclude participation in September 2019.

- Air Products and Chemicals of Pennsylvania, which designed and built a system to capture CO2 from two large steam-methane reformers, which produce hydrogen from methane, in Texas. The CO2 is used for enhanced oil recovery and sequestered. The DOE provided $284 million, and it ended participation at the end of 2017.

The DOE’s remaining $1.54 billion was dispersed among the other 785 R&D projects in much smaller amounts—more than half were for less than $1 million. For 661 of the 785 projects, the initially agreed-upon dollar amount to be covered by recipients was $617 million in cost-share—and the rest mostly received federal grants. About 89% of these 785 remaining projects (698 projects) were involved in R&D of coal technologies, such as coal gasification, and the other 11% were involved R&D of oil and gas technologies, such as development of technologies to find, characterize and recover methane from gas hydrates.

While it is unclear how projects it has funded have fared, the DOE’s full fossil energy R&D portfolio is highly interesting.

FuelCell Energy, for example, got $4 million in funding for a four-year project to test fuel cell carbon capture technology at Plant Barry, a coal plant in Alabama. The DOE also furnished the Institute of Gas Technology with $35 million for a six-year project for a supercritical pilot plant test facility that should be completed by 2022. At Ohio State University, a project, for which the DOE provided $600,000, could revolutionize gas turbine cooling, reducing coolant consumption and increase cooling effectiveness, achievements that could help the gas power industry achieve its goal of 65% combined cycle efficiency. The DOE is also backing projects that could convert carbon-containing material into synthesis gas, and develop rare earth separation and recovery from coal and coal by-products.

Despite Repeated $8B Solicitations, No Fossil Energy Loan Guarantees Have Been Issued

The GAO’s report surveys all R&D funding for advanced fossil energy R&D projects between 2010 and 2017. However, it also studied the DOE’s loan guarantees (under Title XVII), from fiscal year 2006 to August 2018.

While the DOE issued three solicitations during that period for applications for advanced fossil energy loan guarantees—in 2006 for up to $2 billion, in 2008, for up to $8 billion, and most recently in 2014, for $8 billion—no loans have actually been guaranteed as of August 2018, it notes. The report points out that the 2006 and 2008 solicitations were focused on projects that would incorporate CCS, coal gasification, and other beneficial uses for carbon.

It suggests that the solicitations failed in part because “natural gas prices fell, causing a shift in the market, which led to such coal-related projects no longer being economically competitive, according to DOE officials.” The 2014 solicitation attracted 19 applications, and five were “actively moving through the process of review” as of August 2018. These include a 2016 DOE conditional commitment to guarantee up to $2 billion in loansfor Lake Charles Methanol, a project that seeks to produce methanol from gasification of pet coke and capture the carbon dioxide produced for enhanced oil recovery (EOR).

In its report, the GAO noted that the $2.66 billion in funding for R&D came mainly from the DOE’s Office of Fossil Energy (FE), whose mission is to ensure reliable fossil energy resources. Most projects were overseen by the National Energy Technology Laboratory (NETL), which exists under FE as the only government-owned national laboratory (the others are owned by contractors), to provide technical and contract and project management, among other things.

The DOE began providing technical and financial assistance for fossil energy in 1979—under the Jimmy Carter administration. In the 1980s and early 1990s, its fossil energy R&D program primarily focused on slashing pollutant emissions—particularly of sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxide—from coal power plants. Efforts included large scale demonstrations of low-NOx burners, selective catalytic reduction, flue gas desulfurization, fluidized bed combustion, and even IGCC. (Those efforts paid off wildly. For more, see POWER’s July 2017 infographic, “The Big Picture: SO2 Success.”)

According to NETL, in the early 2000s, large demonstrations focused on refining costs of emissions controls and improving byproduct utilization, performance, and plant reliability. Projects included a neural network-intelligent soot-blowing system; conversion of spray dryer solid residue into lightweight aggregate; multi-pollutant control technology with SNCR, in-duct SCR, and low-NOX burners, and a circulating fluidized bed dry scrubber system.

Over the later 2000s, under the Bush and Obama administrations, R&D also focused on enhanced environmental performance and improved economics, demonstrating advanced gasification and mercury control. But R&D also began a marked shift toward addressing carbon emissions from coal combustion. While at first, efforts focused mainly on carbon capture, carbon utilization has also gained importance under the combined concept “carbon capture, utilization, and storage” (CCUS).

[For a full list of large-scale NETL coal demonstrations, see “A List of DOE-Funded Large Coal Demonstrations.”]

Can R&D Rescue Coal Power?

The GAO’s report comes as initiatives to rescue coal power by industry and government are converging amid concerns that nearly 40% of the U.S. coal fleet operating in 2010 has retired, converted to another fuel, or is slated for retirement by 2030.

But though the White House this June confirmed it has directed the DOE to “prepare immediate steps to stop the loss”of coal power facilities—which it claims are “fuel-secure”—the Trump administration also proposed to reduce FE R&D funding in its FY2018 and FY2019 budgets. As the Congressional Research Service noted in an August 2018 primer on CCS, the Trump administration’s proposal was unsupportive of initiatives spearheaded by the Bush and Obama administrations to ramp up R&D on CCS. Congress, however, refuted the Trump administration’s FE R&D budget proposal for FY2018, and instead increased funding by nearly $59 million (9%) compared to FY2017.

This February, Congress also enacted the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018, a part (Title II, Section 41119 of P.L. 115-123) of which amends Internal Revenue Code Section 45Q to increase the tax credit for capture and sequestration of “carbon oxide,” or for its use for EOR or natural gas development. The incentives are notable: Before the enactment, Section 45Q allowed for a tax credit of $20 per ton of CO2 captured and permanently sequestered, and $10 per ton for CO2used as a tertiary injectant, such as EOR.

The credit amounts, adjusted annually for inflation, were increased to $22.48 and $11.24 for 2017, though credits are capped at 75 million tons of qualifying CO2. “With congressional passage of the 45Q tax credit, carbon capture policy has become an important part of the national conversation on energy, job creation and emissions reductions,” declared Brad Crabtree, vice president of fossil energy at the Great Plains Institute and one of two co-conveners of newly formed Carbon Capture Coalition. That group is now actively campaigning for the USE IT Act, bipartisan carbon capture legislation that incentivizes development of direct air capture technology. The bill cleared the Senate Environment and Public Works in May and is awaiting Senate passage.

The coal industry, too, recognizes the significant role R&D could play to secure the future of coal power in markets disrupted by the proliferation of cheap gas and renewables. But it urges a focus outside of CCS.

The National Coal Council (NCC), a 35-year-old nonprofit that serves as an advisory group to the U.S. energy secretary, on October 3, for example, endorsed a reportprepared by its members that outlines an R&D roadmap. Priorities include improving technologies to reduce coal power plant cooling water consumption, treat water effluent, and manage byproducts; improve criteria emissions control systems (and gear them to increased flexible operation); improve co-firing; improve net plant efficiency; as well as development of high-temperature tolerant materials for units undergoing replacement of major subsystems. As significantly, the NCC urges demonstration of advanced ultrasupercritical componentsfor possible retrofit to improve efficiency, capacity factor, and reliability of existing plants.

Notably, however, the NCC’s roadmap does not specifically recommend carbon capture technology development for existing units. It said efforts to do so must consider costs, as well as “other site-specific issues such as access to EOR or other geologic storage options, and the amount of space available onsite to accommodate the equipment to capture and transport CO2.” Still, the NCC appears optimistic that “many types of CO2capture technologies designed for new facilities would also be practical for existing fossil-fired power plants if RD&D can sufficiently reduce costs and mitigate significant negative impacts on plant efficiency.”

—Sonal Patel is a POWER associate editor (@sonalcpatel, @POWERmagazine)