With the increasing number of technical and economic changes affecting the power industry, the value of women in the workforce has never been higher. This follow-up to our 2008 special report, “Workforce Management Lessons from Women in Power Generation,” looks at how having women visible throughout the industry can make it more successful.

For our November 2008 issue, at the suggestion of my predecessor, Dr. Robert Peltier, PE, I researched and wrote “Workforce Management Lessons from Women in Power Generation,” the first substantial examination of women in this industry. Bob was curious about why there were so few women in power. When he went to meetings at plants or with companies serving the industry, he’d usually find, at most, one woman at the table. Things haven’t changed much since then, but if the power industry is to achieve optimal results going forward, employers should look seriously at recruiting women for jobs in all areas, from engineering and chemistry to the crafts and compliance.

One can take a short-term view of the challenges, which might focus on the exit of the Baby Boomer generation and the need to fill jobs, or a longer-term view, which would seek to build a sustainable supply chain that includes a diverse pool of potential future candidates for positions at all levels. In either case, there are increasingly compelling reasons to develop a more diverse workforce.

One is that the new variables that both power generators and their supporting industry partners must juggle—from an increasing number of regulations to new industry entrants to unfamiliar market changes—require something other than business-as-usual thinking and operations. Greater complexity requires greater creativity, which often results from teams that can bring a variety of experiences, perspectives, and problem-solving approaches to the table.

Why Women in Power Matter

Yes, that subhead has a double meaning. Most studies of women in the workplace focus on women in higher-level roles, especially in executive positions and on corporate boards. That’s important, both for women’s value as role models and the economic value they bring to their organizations.

However, especially in fields like power, where women have been traditionally underrepresented, looking at career entry points is equally important. After all, unless women are interested in a field, they are unlikely to enter it, build a career, and reach the highest levels. There are more signs now than in 2008 that efforts to encourage girls and young women to consider science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) education are building momentum. The Engineer Girl website (see the web supplement “Resources for Women in Power Generation” associated with this issue at powermag.com) is just one. Others include local, industry, and government initiatives.

I’ll get to why having women in power matters to the industry shortly, but here’s one reason that having women in power and other STEM fields matters to women: “Women in STEM jobs earn 33 percent more than those in non-STEM occupations and experience a smaller wage gap relative to men,” according to the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP). Another, according to OSTP is that STEM careers “offer women the opportunity to engage in some of the most exciting realms of discovery and technological innovation.”

Women at the Top Improve the Bottom Line

If you’ve been reading or listening to any mass media in recent years, you’ll have heard about some of the many research studies that have found that having women in management and on corporate boards results in higher earnings. That pattern holds true around the world and for different types of businesses, as multiple reports by the likes of McKinsey & Co. have shown.

For a global view of this issue from a woman who holds one of the most powerful positions in the world, consider comments made by Christine Lagarde, the first woman to head the International Monetary Fund (IMF). In a March 2014 interview, Managing Director Lagarde mentioned an IMF study on women in the workforce: “We found that if females were working in the same proportion as men do, the level of [gross domestic product] in a country like Egypt would be up 34 percent, up 27 percent in a country like India but also up 9 percent in Japan and up 5 percent in the United States. All economies have savings and productivity gains if women have access to the job market. It’s not just a moral, philosophical or equal-opportunity matter. It’s also an economic cause. It just makes economic sense. It’s a no-brainer.”

In particular, she noted that Japan and South Korea policymakers “have decided to put women at the center of their budget and policies going forward. Why is that? Well, first of all, they have aging populations and they need to respond to that problem—they need more people to come to the workforce. They have available talented, well-educated, very often hard-working female workers that they can tap.” Does that sound like any scenario in the power industry that you’re familiar with? (For the full interview, visit http://n.pr/QmBjh8.)

Within the power industry, a March report by Ernst & Young LLP (EY), “Talent at the Table: Women in Power and Utilities Index 2015,” found that utilities with more women in leadership ranks performed better than their peers. Its analysis showed that “the top 20 utilities for gender diversity, with a combined average return on equity (ROE) of 8.5%, significantly outperform the lower 20, with a combined average ROE of 7%.” As the EY report notes, “Given the asset-heavy nature of this industry, a 1.5% difference in ROE between the two groups can translate into millions less in profit.”

At the top of its global top 20 list for women in boardrooms is Eskom (South Africa)—with seven women on its 12-member board, followed by Duke Energy (U.S.) and Sempra Energy (U.S.). Looking at senior management teams (SMTs), the utilities with five or more women were:

■ BC Hydro (Canada)

■ CLP Holdings (Hong Kong)

■ CMS Energy Corp. (U.S.)

■ Dominion Resources (U.S.)

■ Empresas Públicas de Medellin (Columbia)

■ Manila Electric Co. (Philippines)—the overall leader, with eight women on an 18-member SMT

■ NRG Energy (U.S.)

■ Singapore Power Ltd. (Singapore)

Whether the CEO is male or female may in some cases be less critical to financial success than whether a company is a regulated utility, with an ensured rate of return, or an independent power producer, subject to the market. In any case, one female CEO in particular, Lynn Good, has been gaining plaudits for her leadership of Duke Energy, in part for her decision to move the largest utility in the U.S. away from wholesale market generation. (See “Duke Energy Generation: Wholesale Retreat” in this issue.)

A Nov. 8, 2014, Fortune.com article asks, “Is Lynn Good the smartest (new) CEO in the energy industry?” The answer that author provides is essentially, yes. In terms of the bottom line, in Good’s first year and a half at the helm, the article notes, Duke “provided a total return of 32%, beating the S&P 500 by almost four points.” (Profits fell in the fourth quarter of last year, however.) True, the company has had several recent difficulties, including troubles concerning its Edwardsport integrated gasification combined cycle facility and coal ash spills, but those problems were many pre-Good years in the making.

Particularly during times of industry stress and change, which the power industry is facing in spades, having a more gender-balanced workforce and leadership can be an advantage. Lagarde has suggested that if Lehman Brothers had been Lehman Sisters, the financial industry catastrophe might have been averted.

To that point, she said, “I do believe women have different ways of taking risks, of addressing issues… of ruminating a bit more before they jump to conclusions…. I’m not suggesting that all key functions and roles should be held by women. But I think that there would have to be a much bigger diversity and a better sharing of those functions and roles. If you look at the studies… it’s apparently very clear now that those companies that have several female directors on their boards and females in their top management actually do better, are more profitable, and actually give a better return to their shareholders.”

The EY report also noted the “glacial pace of change” in the power and utilities industry. Only 5% of board positions are held by women (a 1% increase from last year), while non-executive directors are at 17%, down 1% from last year. In order to benefit from the value of having women in corporate leadership positions (see sidebar “What’s in a Name?”), it helps to have a plan for career development that provides industry entry points all along the way.

What’s in a Name?As this article was being written, POWER Associate Editor Sonal Patel was working on a news story about a corporate name change and passed along this timely anecdote. The French energy group formerly known as GDF SUEZ is changing its name to ENGIE. Deputy CEO Isabelle Kocher, 49, who is soon to replace 66-year-old CEO Gérard Mestrallet, reportedly said the new name looks and sounds like a woman’s first name. Mestrallet said a female name is “a coincidence that doesn’t displease” him, as the company will soon be run by two women, Ms. Kocher and CFO Judith Hartmann. |

So, Why Aren’t There More Women in Power Generation?

Determining the percentage of women in the power industry, even in just the U.S., is difficult. There is no single industry group that gathers such data, even by fuel or technology breakout, and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data is difficult to parse for exactly these purposes. However, BLS data for 2014 indicate that in the “Electrical power generation, transmission, and distribution” industry, women accounted for 23.3% of all employees. Note that this accounts for all job functions across the industry, from power plant operators to line workers to office workers.

Other estimates place women in the industry at between 1% and 25%, depending on the sector. Kristen Graf, executive director of Women of Wind Energy, supplied POWER with a June 2013 National Renewable Energy Laboratory report (“A National Skills Assessment of the U.S. Wind Industry in 2012”) that found: “According to our survey, which only captures a segment of the domestic wind industry, women comprise approximately 20% of the known wind workforce. The variance across occupations is large. Six occupations of the 26 in our survey exhibited a majority of women in their workforce. These six included paralegals, admin/clerical, government regulatory workers, operations and maintenance accountants/bookkeepers, supply chain/purchasing managers, and development finance. The occupations with the lowest female representation were assembly workers, construction laborers, transportation/logistics workers, and wind technicians, each with less than 10%. One note of caution in this section is that according to BW Research staff, companies asked about numbers of female employees tend to over-report the number of women working in their company” (emphasis added).

A 2013 job census by The Solar Foundation found that 19% of all solar workers were women.

I was unable to find numbers for the thermal power sector, despite contacting major industry groups.

Respondents to our 2015 survey (the largest share of whom are working in the coal sector) indicated that the percentage of women in their plant or division was no more than 10%. (For full survey results, see “POWER’ s 2015 Women in Power Generation Survey” in this issue.)

Many, often competing, theories have been advanced to explain the under-representation of women in STEM fields in general and in the power industry in particular. There are surely some women, as well as men, who rule out this industry because many plants are located in remote or sparsely populated areas. Some people enjoy small town, rural life; some don’t. Others will rule out the thermal generation sector of the industry because they don’t want to work in a sometimes noisy and dirty environment. On the other hand, I’ve talked with one woman in charge of a coal yard who beamed when she spoke about her job. Another cohort of workers and potential employees will be interested in only specific generation types—either for environmental reasons or technology reasons. Someone who is fundamentally opposed to fossil fuels is unlikely to seek a job at a coal plant, while someone who is fascinated by physics will likely be drawn more to the nuclear or solar sector than the others. Personal preferences are neither right nor wrong; they just are.

Beyond personal preferences, the reasons for a dearth of women in any given industry are typically a mix of factors that cut across industries and ones that are more industry-specific. For example, an August 2014 Associated Press story noted that the construction industry is increasing its efforts to recruit women. In addition to stereotypes about that industry, the National Women’s Law Center found that “pervasive sexual harassment of women at work sites” was another factor responsible for low numbers of women in construction.

Generally speaking, “Gender bias, workplace exclusion, and a lack of support structures are some of the factors contributing to the lack of women working in engineering and computing,” according to a March 2015 report by the American Association of University Women (you’ll find a link to that report in the “Resources for Women in Power Generation” web supplement associated with this issue in the archives at powermag.com).

In the power industry, shift work may pose an obstacle for some, whereas others may find the work and schedules manageable but the work environment less conducive to job satisfaction. I have heard more than one woman in the power industry comment that you have to have a thick skin and a strong sense of humor to survive the culture of power plants. Some women may be willing to put up with everything from snarky to sexist comments and attitudes; some of those women may have little choice because of where they live or want to live. But others may decide that their energy is better used where it is appreciated.

Some, after giving a particular plant or company a try, may decide that the effort and growing ever-thicker layers of skin just isn’t worth it. Women in that situation, when they can, may decide to move to a different segment of the industry or may leave with their skills and talents to seek their fortunes in completely different areas. (See the previously mentioned survey article for more on job satisfaction and career change plans.)

Even someone as clearly qualified as the IMF’s Lagarde has faced such decision points. When starting out as a lawyer, she interviewed at a high-profile French firm that bluntly told her she’d never be more than an associate—because she was a woman. She rejected their offer. “And I just left because I wasn’t going to waste my time with those people,” she said in the previously mentioned interview. “And I went to another firm which was great and which was based on respect and on equal opportunity for those who delivered.”

The Culture Challenge

How can power companies avoid that sort of talent loss? No solution will be equally successful everywhere, but one effort that is never wasted is cultivating a workplace culture that is conducive to professional success for all workers—men and women, young and old, military veterans and other career-shifters, and promising employees from diverse cultural and economic backgrounds.

Workplace culture is shaped by a combination of leadership, written and unwritten policy, and individual workers at any given location. For example, does a company CEO’s attitude toward women in general and women within the company demonstrate respect or something else?

A recent case in point comes from Schneider Electric. A March 10 press release announced that Chairman and CEO Jean-Pascal Tricoire was awarded one of five awards from the Women’s Empowerment Principles (WEP) event this year “for his demonstrated commitment to and implementation of policies that advance and empower women in the workplace, marketplace and community. The 2015 Business Case for Action Award recognized [Schneider Electric] for its Diversity and Inclusion policy, which prioritizes communicating the business case for diversity and creating a company-wide gender balance environment that extends beyond the parent company to more than 10 Schneider Electric CEOs of its international branches in countries from Viet Nam [sic] to Turkey.”

Commenting on the award, Tricoire said, “Addressing gender diversity and equality is a business and growth challenge. It is a key priority which impacts not only the performance of our organization, but also its reputation as world-class employer. For many reasons, that we know all, gender diversity and equality is no more an option but a business imperative!”

Fields that have been historically male-dominated may have a tougher time adapting to these new business imperatives and cultural shifts. Doing so requires more than just hiring women or even setting up mentorships (see sidebar, “Fairbanks Morse Leverages the Benefits of Diversity”).

From Education to Career

One explanation for the small number of women in the power industry has been that too few women have the right technical education. Assuming that is true, measures to encourage more girls and young women to consider STEM education would be a necessary first step toward increasing their visibility. But even once women enter STEM fields, they may not stay in them. One recent three-year study of 5,300 women who had earned engineering degrees within the previous six decades found that, “Compared with other skilled professions such as accounting, medicine and law, engineering has the highest turnover of women.”

According to a report by National Public Radio, the study, by University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee psychologist Nadya Fouad, “found that only 17 percent of women left engineering because of caregiving reasons, which Fouad said dispels the notion that pregnancy plays a big part in keeping women out. But she does note that many of those who did leave to stay home with children did so because their companies did not offer flexible enough work-life policies.”

The same NPR report quoted aerospace engineer Elizabeth Bierman, president of the Society of Women Engineers, as offering a slightly different perspective: “The work environment may be one reason, but for the majority it is not the case.”

A Society of Women Engineers retention study “found that although women do leave the engineering workplace faster than men, they do so for a variety of reasons. Many of those reasons, such as lack of work-life balance, also resonate with men, Bierman said.”

Bierman told NPR that companies hoping to retain both women and men should improve their work-life balance policies. Even that concept can be contentious. When I spoke earlier this year with Cindy Simpson, chief business development officer for the Association for Women in Science, she noted that when conducting surveys, her group uses the term “work/life satisfaction.” There’s no such thing as “balancing” the two, she pointed out. Many women and men in the workforce would agree.

Yet another suggestion for attracting and retaining women in engineering was offered by Lina Nilsson, innovation director at the Blum Center for Developing Economies at the University of California, Berkeley, in an April 27 New York Times op-ed piece. Her experience suggests that “if the content of the work itself is made more societally meaningful, women will enroll in droves. That applies not only to computer engineering but also to more traditional, equally male-dominated fields like mechanical and chemical engineering.” Nilsson’s examples include “designing affordable solutions for clean drinking water, inventing medical diagnostic equipment for neglected tropical diseases and enabling local manufacturing in poor and remote regions.”

Nilsson has found the same dynamic at other engineering schools: “The undergraduate-level international minor for engineers at the University of Michigan reports that 51 percent of its students are women. Those women are predominantly majoring in some of the oldest and most traditional engineering fields—industrial operations and mechanical and chemical engineering—where, arguably, gender stereotypes are most entrenched.” Similar engineering programs at other schools that are focused on “societally meaningful” challenges “also report significant increases in the numbers of women participating.” None of these programs “were designed with the main goal of appealing to female engineers, and perhaps this is exactly why they are drawing us in,” Nilsson suggested.

Note that, although many jobs in the power generation industry do not require an engineering degree, studies such as those mentioned often serve as a proxy for the range of positions because there is more readily available data to study.

Although programs focusing on “socially meaningful” engineering may attract more female students than traditional engineering programs, some women in the traditional power sector see plenty of societal value in what they do. Take, for example, Sara McMurray, a materials scientist for ADA Carbon Solutions LLC (Figure 2), who commented on the “positive impact” her job has.

|

| 2. Positive results. Sara McMurray, materials scientist for ADA Carbon Solutions LLC, says, “I like working in the power industry because I feel that the work is relevant, important, that I have a positive impact, and the job engages a very diverse skill set.” Courtesy: Sara McMurray |

And then there are the women of Rawhide Energy Station in Colorado, who, organized by Plant Chemistry Supervisor Gale McGaha Miller, sent several photos of women at work (Figures 3 to 5) in response to a request posted to the POWER -sponsored Women in Power Generation (WIPG) LinkedIn group. Platte River Power Authority owns and operates the plant north of Fort Collins.

|

| 3. Rawhide Energy Station Plant Chemistry Supervisor Gale McGaha Miller. “I’ve been interested in water purification since sixth grade, and high-quality boiler makeup water is essential for fossil units. It feels great to provide all the water treatment needs for the Rawhide Energy Station, one of the cleanest, most efficient coal-fired power plants in the nation, if not the world.” Courtesy: Platte River Power Authority |

|

| 4. Rawhide Energy Station Plant Buyer Dawn Miller. “I am very thankful to have the opportunity to work for Platte River Power Authority at the Rawhide Energy Station. What a very productive work place with great work/life balance. I find that working here is very interesting and rewarding. You couldn’t ask for a better group of people to work with.” Courtesy: Platte River Power Authority |

|

| 5. Rawhide Energy Station Occupational Health & Safety Specialist Natalie Parson. “What we do here every day provides so many opportunities for people in their daily lives—the power we provide is so important to how we all live. I work with wonderful people and am glad to be a part of keeping them safe, so they can go home to their families at the end of the day.” Courtesy: Platte River Power Authority |

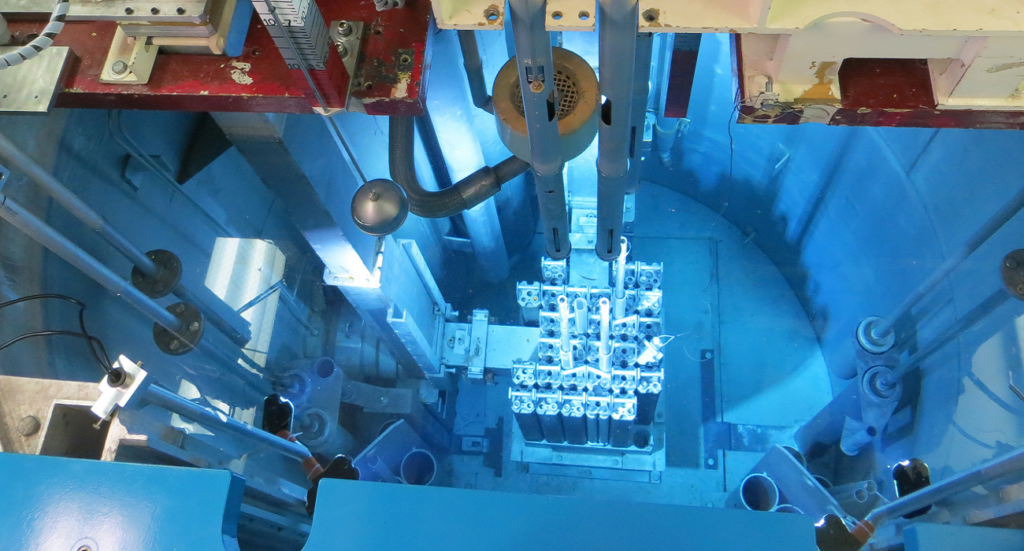

Rawhide Plant Operator Dana Belinski (shown in the photo that opens this article), said, “After 27 years at the Rawhide Energy Station, I feel very fortunate to have had the opportunity to make this my career. I work with a great group of people and a caring company.”

What Has and Hasn’t Changed Since 2008

Over the past seven years, more professional development and networking opportunities for women have developed across STEM fields and the energy industry (including POWER’ s Women in Power Generation group on LinkedIn). There has also been high-profile encouragement of professional women across fields, with Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In book and movement being arguably the most notable.

But a career in power generation still poses gender-specific challenges. Among them (unless you work at a plant like Rawhide) can be the loneliness of being the lone woman on a site. Some companies are paying attention to the fact that such under-representation short-changes both women and their employers. Both men and women are beginning to recognize the value of developing more gender-balanced teams, as was evident by the number of men who were in the audience for this year’s Women in Power Generation panel discussion at the ELECTRIC POWER Conference & Exhibition in Rosemont, Ill. (Figure 6).

|

| 6. Powerful panel. At the 2015 ELECTRIC POWER Conference & Exhibition in Rosemont, Ill., on Apr. 22, Colleen Campbell (AECOM, far right), moderated a Women in Power Generation panel discussion with impressive leaders. Left to right: Tracy Ortiz, fuels superintendent, Tucson Electric Power; Sharon Pfeuffer, director of engineering, DTE Energy; Karen Peery, vice president, IT, Exelon Generation LLC; Angela Deuitch, public affairs manager, NiSource Corp.; Teresa Mogensen, vice president, transmission and operations services, Xcel Energy. Source: POWER/Gail Reitenbach |

Though we don’t have enough space to summarize the entire session here, a few details will indicate the breadth, depth, and value of comments shared.

The companies the panelists work for have a variety of professional development and leadership programs for both men and women, but one of the most unusual is an employee resource group sponsored by DTE Energy—an elder care support group. Sharon Pfeuffer, director of engineering at DTE (and a member of POWER’s Generating Company Advisory Team), noted that while employees and employers typically anticipate work/life adjustments driven by children, few have come to grips with the challenges of managing the multifaceted concerns of aging parents. Especially as employees, often women, reach higher levels in their organizations, they may also become responsible for managing the affairs of the older generation. Workplaces that can provide access to support services for these challenges can help retain the presence and dedication of employees in whom they have invested years of development.

In the question and answer period, one man asked, “What mistakes do you see men making as managers?” Karen Peery, vice president, IT at Exelon Generation LLC, immediately responded, “You’re brave!” Pfeuffer followed with, “Thanks for standing up and asking. It’s understanding where some of the gaps are.” Before the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission existed, the issues were more obvious—like being fired for being pregnant. Now the issues are “more subtle and unintentional,” and “women have some of the same biases,” Pfeuffer said.

Angela Deuitch, public affairs manager for NiSource Corp., noted that the younger generation wants more flextime. Teresa Mogensen, vice president, transmission and operations services for Xcel Energy, added that you have to “actively think about diversity” in hiring and building a team. Peery suggested another strategy that can work while transitioning to more-diverse teams: Have diverse individuals from other teams join yours periodically so you can begin to understand the value of multiple perspectives and backgrounds.

Mogensen emphasized that in this industry, where engineers are traditionally thought of as awkward and poor communicators, “The communication skill is key, whether you are male or female.” Tracy Ortiz, fuels superintendent at Tucson Electric Power, agreed, noting that she’s received feedback from some of her team that she’s the best communicator they’ve had for a boss.

Opportunity, Not Preference

Did you happen to watch the 2014 WGN TV series Manhattan, about the interplay of personal and professional lives on “The Hill” (Los Alamos, N.M.) during development of the first atomic bomb? One of the characters was Helen Prins, a PhD physicist played by Katja Herbers. In one episode she tells a male colleague that she knows a black man has a better chance of having a post-war academic career than she does. So as long as there’s a war, she gets to do what she loves and is good at. After the war, she says, her best hope is an adjunct position at a no-name college. An equal opportunity to compete and contribute wasn’t an option in that era.

Ultimately, it’s not about how many women, or how many people of color, or how many individuals of other under-represented groups are employed by any industry. It’s about ensuring that unnecessary obstacles aren’t placed in the path of those who could be good employees. As Terri Omatick, principal for the power sector at Stantec, a design and consulting company, told me, her company doesn’t promote women above men, but women are “given an equal opportunity” to add their unique voice to any meeting or professional opportunity.

We invite the other women in power to share their stories, corporate best practices, as well as team and corporate benefits achieved through diverse workforces. You can start a discussion on our LinkedIn Women in Power Generation group page and/or add a comment below this article online at powermag.com. ■

— Gail Reitenbach, PhD is POWER’s editor.