The Aug. 4–6 U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit shed light on the power plights faced by sub-Saharan African countries, but it also highlighted their massive power potential and the array of solutions under consideration to resolve Africa’s energy crisis. Here are a number of key insights gleaned from discussions at the summit—the first a U.S. president has held with African heads of state and governments—and peripheral events during the three-day event.

1. Economic growth in some African countries is booming. GE Chairman and CEO Jeff Immelt perhaps summed it up the best as he opened the company’s sponsored “Africa Ascending” event on Aug. 4: “Growth in Africa is real, and is happening now,” he said. Over the past 10 years, the continent has seen an average gross domestic product (GDP) growth of more than 5% per year—more than any country of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Six of the world’s 10 fastest-growing economies are in Africa.

2. But Africa’s current power situation is precarious. While Africa is highly diverse and rich in natural resources, its development has been impeded by a number of challenges. Foremost among them, arguably, is its crippling shortage of electricity. Much of the continent is plagued by regular blackouts and brownouts, and emergency power sources cost too much for many homes and businesses.

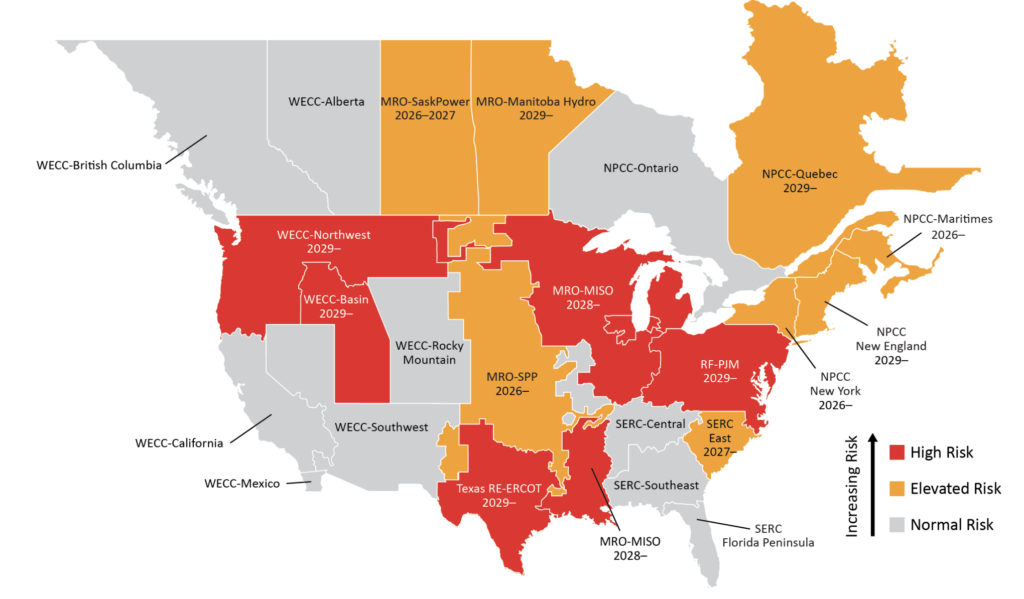

Here’s one startling statistic: 70%—or 600 million people—of the population of sub-Saharan Africa are without electricity. That means, of the 1.2 billion people in the world that live without electricity, half are in sub-Saharan Africa. Here’s another: Compared to the U.S., which has 3,360 MW per million people, sub-Saharan Africa has just 91 MW per million people.

Want more? Among the 20 countries in the world with the highest deficits in access to power, 12 are in sub-Saharan Africa—and eight of those 12 access rates are below 20%. “To put that in perspective, over the course of a year, a refrigerator in the U.S. uses six times more electricity than an average citizen of Tanzania,” notes the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). And, as staggering: “It takes an average Ethiopian two years to consume the amount of electricity an average American uses in just three days.”

3. Power Africa’s scope and funding has vastly increased. President Obama’s June 2013–launched “Power Africa” initiative to add more than 10 GW of new, “cleaner” power generation capacity got three times bigger during the summit. On Aug. 5, the president pledged a new level of $300 million to “expand the reach” of Power Africa and meet a new aggregate goal of 30 GW of additional capacity.

The initiative has meanwhile gained the backing of the World Bank, which has committed $5 billion for projects in six initial Power Africa “focus” countries: Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Liberia, Nigeria, and Tanzania. The African Development Bank has pledged $3 billion, approving about $670 million in support for those same six focus countries, where the International Energy Agency (IEA) claims 40% of Africa’s population without power (about 240 million people) live. The government of Sweden, too, has backed the initiative, committing $1 billion to help upgrade transmission and distribution in sub-Saharan Africa.

4. U.S. interest in Africa’s power sector is no challenge to China’s vested interest in the continent. The seemingly large pledges compare poorly, however, with what appears a bottomless well of direct aid and loans for energy and other infrastructure in Africa from China. China this year became Africa’s biggest trade partner, and the country has acquired immense political clout as well as lucrative contracts. Chinese state banks are financing the continent’s biggest hydropower projects, such as the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, as well as seemingly risky investments such as coal mines in economically flailing Zimbabwe to help ease power shortages.

But at the summit in Washington D.C. this August, President Obama said that the U.S. is interested in Africa for more than just its natural resources. “We don’t simply want to extract minerals from the ground for our growth. We want to build partnerships that create jobs and opportunity for all our peoples, that unleash the next era of African growth,” he said.

5. Private sector interest and participation is surging. According to the IEA, at least $300 billion in private sector funds are needed for sub-Saharan Africa to achieve universal access by 2030. So far, under Power Africa, total private sector commitments have reached $20 billion.

Transactions to build 2.8 GW of projects are being concluded, and the initiative is actively supporting another 5 GW of transactions, President Obama announced in August. Projects undertaken in the first year include ongoing negotiation of Corbetti Geothermal, the first phase of a potential 1-GW geothermal project and Ethiopia’s first independent power project; advancing nearly 500 MW of wind projects in Kenya; financial support for a 10-MW mini-hydro and a 5-MW solar project in Tanzania; and supporting power sector-wide privatization efforts in Nigeria.

6. Some roadblocks will seem insurmountable. Funding is only one part of the solution. Experts note that investment and progress has historically—but significantly—been hampered by poorly designed regulations, corruption, governance challenges, political uncertainties, and a general lack of technical and managerial expertise. All those issues still pose roadblocks for doing business in the continent.

For many participants at the summit, those challenges will have to be met creatively and with innovation. “We are not for African pessimism or Africa optimism, we are for African realism. People need to see Africa as it is,” said Dr. Mo Ibrahim, founder and chairman of the Mo Ibrahim Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to promoting African development, at the GE Ascending Africa event. Aliko Dangote, president and CEO of the Dangote Group, put it another way: “Are you going to wait until corruption is zero to invest, or are you going to invest and also encourage people [to fight against corruption]?” he asked.

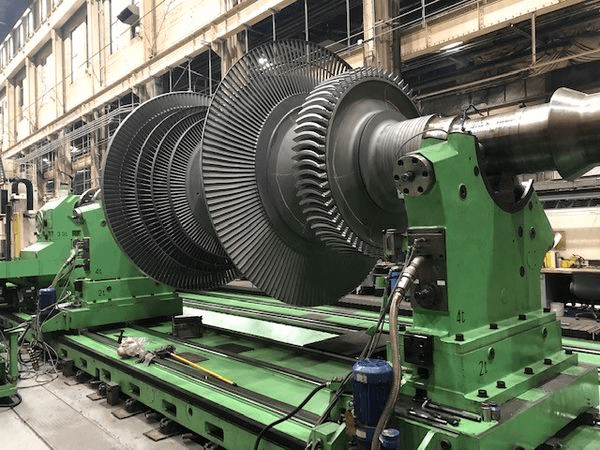

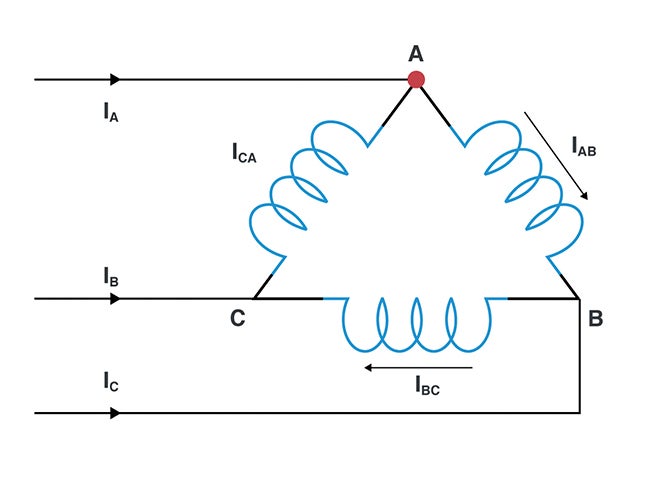

7. Some African countries are making progress toward reform, though with limited results. In 2013, Nigeria embarked on one of the boldest privatization initiatives in the global power sector over the last decade, breaking up the dysfunctional National Electric Power Authority and putting 80% of the government’s stake in 10 generating companies up for sale, with a transaction cost of about $3 billion. The measure is expected to increase generation over the next five years by more than 7.5 GW, doubling the current capacity for all of Nigeria—but it continues to be plagued by delays, uncertainties (such as just how dilapidated infrastructure has become), corruption, and other roadblocks, officials at the summit revealed.

Ethiopia, too, is engaged in negotiations that will introduce its first privately owned power producer, though some observers noted that the actual process would prove slow and ridden with controversy. Ghana is also committed to significant reforms to attract private investment. This August, that country and the U.S. signed the five-year Ghana Power Compact, which calls for investments of up to $498.2 million to catalyze more than $4 billion in private investment.

Meanwhile, Power Africa and other donors are “working closely” with countries like Liberia and Kenya to encourage adoption of new frameworks for energy legislation, officials at the summit said. USAID said these “proven commitments” to reform have specifically spurred commitments from private investors. Heirs Holdings has committed $2.5 billion of investment and financing for energy projects over the next five years; Aldwych International is catalyzing $1.1 billion to develop wind power in Kenya and Tanzania; and GE is committed to bringing 5,000 MW online by providing technology, expertise, and capital in Tanzania and Ghana.

8. The focus has expanded to encapsulate off-grid solutions. As World Bank President Dr. Jim Yong Kim pointed out, only 1% of the world’s private investment in energy is going to Africa. He asked whether the continent, in the context of these limited capital resources, should prioritize centralized power or focus on off-grid solutions. Both alternatives can be part of the solution, he concluded. “In terms of large-scale installed capacity, we really have to look at hydro all over again,” he said. Projects like the Grand Inga dam in the Democratic Republic of Congo could substantially increase total installed capacity. But diversification with renewables and other fuel sources will be equally important, he said.

Meanwhile, along with Power Africa, the White House is pushing “Beyond the Grid,” an initiative announced at the June 2014 U.S.-Africa Energy Ministerial in Ethiopia, to foster private investment in off-grid and small-scale energy solutions. The initiative was founded by 27 partners that have committed to invest more than $1 billion over the next five years to set up distributed energy solutions across the continent.

9. Renewables are poised to be an important part of the solution. Participants in the summit brought it up again and again: The region has a massive renewable potential that is barely exploited.

It has, for example, 10% of the global economically exploitable water reserves but is using only 17% of its 150-GW hydropower potential. Most African countries receive 325 days of sunlight a year and daily solar radiation between 4 kWh and 6 kWh per square meter. East Africa, in particular, harbors a 15-GW geothermal power potential. With its urgent power demand, and the consideration that it can take years to develop the necessary infrastructure to deliver power across large, remote areas, renewables are looking increasingly attractive for future installations.

10. Africa is determined to bridge its energy gap with fossil fuels. Nigeria’s Minister of Power Chinedu Ositadinma Nebo perhaps said it most poignantly. “Africa is hugely in darkness. Whatever we can do to get Africa from a place of darkness to a place of light . . . I think we should encourage that to happen,” he told attendees at the GE Ascending Africa event.

Renewables alone are not yet able to provide Africa’s needed baseload power for industrial growth, and it is important to let Africa “use its resources,” Nebo said. New, massive oil and gas discoveries in countries like Tanzania and Mozambique will mean those countries will grow their gas capacities, he said. Tanzanian Minister of Power Sospeter Muhongo, who outlined his country’s goals to grow its GDP by 9% annually, agreed.

The West’s industrialization was fueled with coal, and Europe is “going back to coal,” argued Muhongo. Africa’s greenhouse gas emissions are “completely negligible ” compared to other countries. “We will start intensifying the utilization of coal,” he said, drawing applause from event attendees. “Why shouldn’t we use coal when there are other countries where their [carbon dioxide emissions] per capita is so high? . . . We will just go ahead.”

Africa’s dependence on fossil fuels may even be encouraged by international development organizations. The World Bank’s Kim, who spoke about the “energy apartheid” afflicting Africa, stressed that for Africa to succeed, fossil fuels must be in the mix. “We have made a clear commitment to battle climate change. [But we are also] serious about African access to energy.

“In certain places where the only option is coal, we have said that we’re going to have to look at that, and look at that seriously,” he said.

—Sonal Patel, associate editor (@POWERmagazine, @sonalcpatel)