PJM Interconnection will not run a base residual auction (BRA) until the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) approves recalculated Minimum Offer Price Rule (MOPR) floor prices for new and existing resources as directed by the federal entity’s ground-shaking Dec. 19 capacity market order. But when that will occur is still highly uncertain.

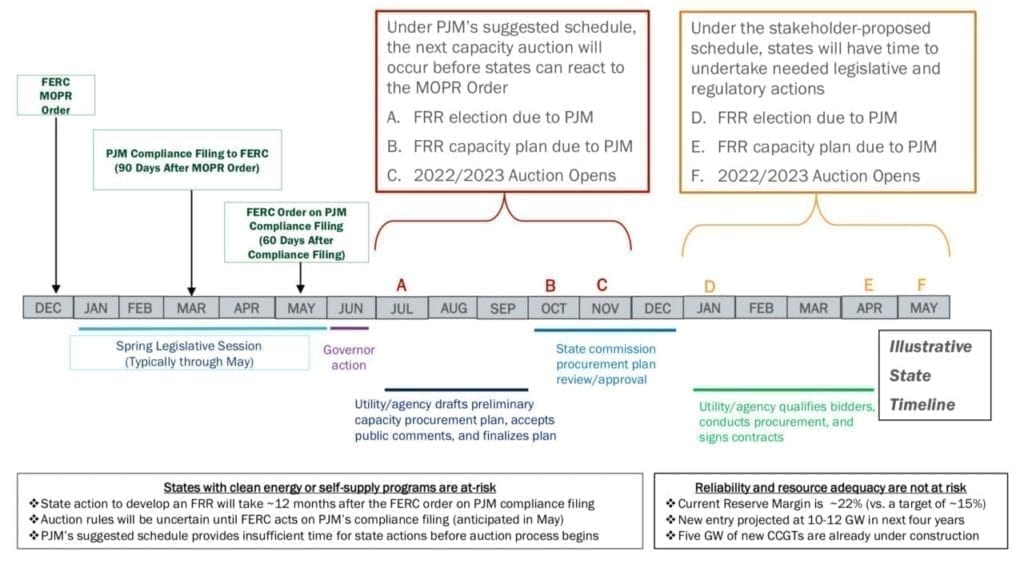

In a presentation at the grid operator’s Jan. 8 Market Implementation Committee meeting, Paul Scheidecker, senior lead engineer of PJM’s Capacity Market Operations, noted PJM has not determined a proposed schedule for the 2022/2023 and 2023/2024 BRAs, but he said that “even with [an] accelerated schedule,” auction timelines will be “delayed up until the 2024 [BRA] for 2027/2028,” which essentially means delays for five auctions. Schedules will depend upon a timely FERC order on PJM’s compliance filing, which is due on March 18.

After FERC’s approval, PJM will embark on pre-auction activities for the 2022/2023 auction. Pre-auction activities typically span nine months, but the “majority happens in the 6 months” prior to an auction, Scheidecker explained. However, he urged PJM and stakeholders to look for opportunities “to condense pre-auction activity timelines or otherwise accelerate the auction timing.”

Meanwhile, as Adam Keech, PJM vice president of Market Operations, told stakeholders Wednesday, PJM has much to accomplish before it can submit a compliance filing to FERC within the tight 90-day timeframe that the Dec. 19 order gives it.

[For an in-depth look at FERC’s Dec. 19 order, see, “The Significance of FERC’s Recent PJM MOPR Order Explained.”]

First, PJM, whose footprint extends across 13 states and the District of Columbia, will need to update its Open Access Transmission Tariff—a document that forms the skeleton of PJM’s operations—to expand the MOPR’s application to all units receiving state subsidies under FERC’s broad new definition of “state subsidy,” as well as the long list of exemptions. Then, it must also develop and submit new floor prices for all resource classes, Keech said.

FERC’s order determined that in calculating the MOPR for new resources—generators which have not cleared an annual BRA or an incremental auction—PJM should use the net cost of new entry (CONE). CONE reflects a new resource’s capital investment and fixed operations and maintenance expenses, he explained. Meanwhile, existing resources—which FERC’s order redefined as having successfully cleared an auction, executed an interconnection construction service agreement, or an unexecuted interconnection agreement filed by PJM at FERC prior to the order—should use the net avoidable cost rate (ACR). ACR reflects an existing resource’s annual “going-forward” costs—costs that would be avoided if the unit was to retire—but which do not incorporate costs to enter the market, essentially reflecting a “resource’s lower threshold to remain in market than to enter it,” he explained in a presentation. “Net CONE and Net ACR remove expected energy and ancillary service (E&AS) market revenues,” and it reveals “the capacity revenue necessary for a resource to remain profitable,” he noted.

PJM will also need to calculate CONE values for new demand response with behind-the-meter generation and energy efficiency, and many other resource types—such as black liquor, coal mine gas, and landfill gas, for example—will need CONE values in addition to what PJM originally filed, Keech said. Finally, PJM’s compliance proposal will also need to establish updated auction timelines for the 2022/2023 and 2023/2024 delivery years, as well as include modified schedules for implicated incremental auctions, he said.

PJM Seeks Input from Stakeholders on How to Proceed on MOPR Order Compliance

PJM will begin the mammoth task under new leadership. Noting it was his third day on the job as PJM’s new president and CEO, Manu Asthan said PJM’s primary purpose for the Jan. 8 meeting was to gather input from stakeholders. “Obviously this is a complicated issue and there are very different perspectives in our stakeholder group related to this order,” he said. “So we’re going to have to sit down and weigh what we think of all of the input that we’ve received. But we’re not going to do that until after we have received the input.”

But as publicly available presentations submitted for discussion at the meeting suggest, PJM’s many stakeholders, including generators that participate in the wholesale electric market, have a variety of concerns about the order. Many want clarification on different parts of the order. And while several generators urged the grid entity to hold the forthcoming annual auction without delay, others called on it to file an extension for submission of its compliance proposal to FERC to iron out pressing concerns.

Competitive generator LS Power, for example, lauded FERC’s order as a “pragmatic approach to striking the appropriate balance between grid reliability and states’ desires to support certain resources.” Addressing concerns from the wider industry and Commissioner Richard Glick, who issued a scathing dissent of the order on Dec. 19, the company posited that the order “does not prevent states from determining their resources,” nor is the order “expected to deter renewable energy projects as those projects do not rely on the capacity market to support investment.” LS Power added, pointedly: “In fact, wind and solar resources comprise only 1.2% of PJM’s capacity requirement.” Non-exempt subsidized units may also continue to participate in the auction on a competitive basis by “rejecting the state subsidy or petitioning PJM for the unit-specific exemption,” it said.

However, echoing other competitive generators, including Calpine and Vistra Energy, LS Power urged PJM to “promptly” resume the two delayed BRA auctions, asking that the 2022/2023 event be held no later than August 2020, and the 2023/2024 auction be held by year-end 2020. It also asked for guidelines for unit-specific exemptions, as well as clarifications for the treatment of aggregated distributed energy and energy efficiency resources, and significantly, the definition of “subsidy” as it applies to regional cap and trade programs, such as the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI).

Calpine, which filed the 2016 complaint that partly spurred FERC’s Dec. 19 order, reiterated that subsidies harm competitive markets and cause uncertainties for generators that depend exclusively on wholesale electric markets for revenue. “The order is not a war on renewables nor is it a preference for certain technologies over others; rather, it is a clear indication by FERC that it will not permit the competitive markets that it oversees to be undermined by state actions,” it said. “There is nothing to debate—FERC issued its order, an order we have been waiting for over a year, and it’s time to proceed,” it added. “Investment and retirement decisions cannot be made until the BRA is run; 18 months have passed, and it is now PJM’s responsibility to hold the auction as soon as possible.”

States May Need More Time to Address the Order

Exelon, a utility that lobbied for many of the legislative measures to keep its uneconomic nuclear plants in Illinois and New York open—and that failed to clear a record amount of nuclear capacity at PJM’s last BRA—however, urged PJM to accommodate all states in its footprint by scheduling the next auction with “reasonable time” for legislative and regulatory action “to avoid over-payment by consumers under the new MOPR.” Some states will require a year to respond to FERC’s MOPR order, it said.

Exelon also called for several clarifications in the compliance filing, including that utility distributed energy and energy efficiency programs in retail choice states should quality as “existing” resources despite daily customer switching, and that RGGI does not comprise an action subsidy to any resources.

PSEG, which owns more than 8 GW of merchant generation in PJM’s footprint, as well as 3.6 GW of nuclear generation in New Jersey that receives zero-emission credits, urged states with clean energy programs to evaluate a fixed resource requirement (FRR) option, noting that the MOPR creates a “double payment” risk for state-supported resources. It also called on PJM to address FRR implementation and time auctions appropriately.

American Municipal Power (AMP)—a public power cooperative that has said the order threatens the public power business model because it deems it a subsidy—urged PJM to request more time and seek an extension for its compliance filing. That could avoid “further litigation, delays, and uncertainty,” and “ensure transparency, inclusive of [PJM’s independent market monitor’s] feedback,” AMP said. It also called for a discussion on how PJM would “inoculate itself and/or prepare for any reversals if rules change from anticipated future litigation,” such as rehearing requests and filing related to the Federal Power Act.

AMP offered a long list of recommendations to remedy what it suggests is PJM’s inexperience with the public power business model. It suggested, for example, that PJM develop “multiple CONE values for each technology type by business model”—such as for merchant and non-merchant businesses. The importance of the issue could not be understated, it said. “Repeated rule churn such as this MOPR Order only serve to reinforce the comments we have made and continue to believe in wholeheartedly—self-supply serves to insulate our members and our not-for-profit organizations from otherwise unhedgeable price volatility and regulatory uncertainty,” it said. “If not ever more apparent to us all then now, [the reliability pricing model, PJM’s name for its capacity market ] is not a market but instead an administratively determined, non-market construct with no end in sight for litigation and major modifications that has now severely crippled prudent investment decisions for future new build.”

EPSA Explains Significance of MOPR Order

As the day-long PJM Market Implementation Committee meeting unfolded, the Electric Power Supply Association (EPSA) on Jan. 8 separately published an “explainer” that lays out how the MOPR could affect its members, which are competitive power suppliers that own and operate 150 GW of capacity nationwide.

In its document, EPSA lauded FERC’s action as having helped “resolve regulatory uncertainty and uphold competitive markets.” Addressing industry-wide criticism that the order serves as a “bailout” for fossil generators, EPSA stressed that many of its members, including Vistra Energy, NRG Energy, Calpine, Competitive Power Ventures, BP, and others have adopted emissions reductions goals, joined the Climate Leadership Council, and supported tools such as carbon-pricing to help advance clean energy objectives. “At the national level, EPSA members have invested in generation facilities that today include nearly 4,000 MW of capacity from renewable resources in addition to increasingly efficient natural gas plants,” it noted.

FERC’s order “does not stand in the way of continued renewable integration or our shared environmental goals; it simply directs us to do so using tools consistent with the competitive market,” EPSA said. “We share Americans’ collective goals when it comes to building a reliable, affordable, and clean energy future. That is exactly why we must keep competitive markets intact—well-functioning, transparent, competitive energy markets are the most effective way to encourage sustainable environmental progress without harming reliability or burdening consumers with unneccessarily high costs.”

EPSA, which has battled a variety of out-of-market interventions in competitive markets across the nation, noted approaches in FERC’s order could be adopted by other U.S. wholesale electricity markets. However, it pointed specifically to California ISO as an example that “reveals the pitfalls of relying on intermittent resources as a substitute for firm capacity.” CAISO, it noted, has been forced to use reliability must run (RMR) contracts to obtain firm capacity as the share of intermittent renewables soar. FERC’s MOPR order “provides a pragmatic approach to avoid the challenges currently being faced by California,” it said.

At PJM, “Competitive power suppliers have invested in renewable resources in PJM at their own risk without subsidies or a guaranteed rate of return from customer bills,” said EPSA. However, FERC’s order will only affect the capacity portion of the market for new renewables, which, EPSA said “currently account for a small portion of revenue for those developers.” The order does not apply to existing renewables, whether state-sponsored or not, it noted. Out of 180 GW of generation in PJM, including 15 GW of installed wind and solar capacity, only 2 GW of renewables cleared in the capacity market in the 2018 auction—“accounting for just 1% of capacity being sourced from wind and solar capacity,” it said.

FERC’s order, meanwhile, also applies to any resource receiving a state subsidy, “including outdated, costly nuclear and coal facilities such as those recently granted support in Ohio,” EPSA said. “There already exists a Unit Specific Exemption process that remains in place for resources that believe their true costs, excluding subsidy payments, are below the minimum price floor established by PJM. If a resource’s true cost is below the floor price [the “MOPR level”], those resources may be permitted to offer into the auction at their lower price,” it explained.

EPSA also rejected criticism that the order infringes on states’ rights. “It does address state policies’ impact on federally regulated wholesale power markets,” it said. “It bears remembering a bit of history when understanding the origins of FERC’s Order. In January 2018, FERC submitted a letter to the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals supporting the Court’s later finding that zero-emission credits (ZECs) did not preempt federal law. However, in that same letter, FERC argued that the appropriate place to mitigate the effects of state subsidies was in the FERC jurisdictional markets. So, while the ZECs and other subsidies may be legal, FERC still has a mandate to ensure that the wholesale market is just and reasonable. The FERC Order does just that.”

—Sonal Patel is a POWER senior associate editor (@sonalcpatel, @POWERmagazine).