A divided Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) issued a long-awaited order on Dec. 19 in which it directed PJM Interconnection to dramatically expand its Minimum Offer Price Rule (MOPR) to nearly all state-subsidized capacity resources. The order will have a significant impact on PJM’s capacity market. While it was no surprise that the decision immediately elicited broad reactions from the wide swath of generators and states it affects, the order deserves a close look within its rich context. Here is all of it explained.

What Happened?

FERC’s commissioners last week voted 2–1 to direct PJM—the nation’s largest regional transmission organization (RTO) whose wholesale competitive market covers all or parts of 13 states and the District of Columbia—to require that nearly all state-subsidized power resources, inside and outside PJM’s footprint, hit a PJM-determined price floor to participate in PJM’s forward-looking capacity auctions.

It did so by adopting a PJM proposal that will essentially extend the grid operator’s MOPR—which currently applies to new natural gas-fired units—to include new and existing capacity auction resources of all fuel types, no matter the size, that receive or are entitled to receive “state subsidies.” As experts noted, the order only exempts specific resources from the rule—and these include non-subsidized existing resources that have previously cleared auctions and non-gas “merchant” resources built without subsidies outside of PJM-operated markets.

FERC also broadly expanded the reach of “state subsidy,” a term it created to replace “out-of-market payments.” The new definition encapsulates:

A direct or indirect payment, concession, rebate, subsidy, non-bypassable consumer charge, or other financial benefit that is (1) a result of any action, mandated process, or sponsored process of a state government, a political subdivision or agency of a state, or an electric cooperative formed pursuant to state law, and that (2) is derived from or connected to the procurement of (a) electricity or electric generation capacity sold at wholesale in interstate commerce, or (b) an attribute of the generation process for electricity or electric generation capacity sold at wholesale in interstate commerce, or (3) will support the construction, development, or operation of a new or existing capacity resource, or (4) could have the effect of allowing a resource to clear in any PJM capacity auction.

The 93-page Dec. 19 order follows FERC’s crucial market shakeup in June 2018, when commissioners voted 3–2 to reject approaches filed by PJM to reform its capacity market. In that order, the federal regulatory entity acknowledged that the integrity and effectiveness of PJM’s capacity market has been increasingly and “untenably threatened” by state subsidies for preferred generation resources.

In the June 2018 order, specifically, FERC found “out-of-market payments”—which it then defined as revenue that a state provides to a market supplier, including, for example, zero-emission credits (ZECs) and renewable portfolio standards (RPS) programs—render PJM’s Open Access Transmission Tariff (a document that forms the skeleton of PJM’s operations) “unjust and unreasonable” because the MOPR fails to address the price-distorting impact of resources receiving state support. However, FERC in June 2018 left the issue unresolved, saying it was unable to make a final determination regarding a “reasonable replacement rate” for PJM’s tariff based on the existing record.

While FERC had initially committed to issuing replacement rules by January 2019, the issue remained in limbo for more than a year, causing extraordinary uncertainty with major implications. PJM, for example, on Oct. 1 confirmed suspension of all deadlines and activities related to the base residual auctions for the 2022/2023 and 2023/2024 delivery years, and it had suggested it could also suspend approaching deadlines for the auction to be held in 2020. Meanwhile, compounding FERC’s inaction was that the five-member commission is currently functioning with only three commissioners, following the death of Commissioner Kevin McIntyre in January 2019, and the August 2019 departure of Commissioner Cheryl LaFleur. Commissioner Richard Glick, meanwhile, was recused from the cases until Nov. 29, 2019, owing to an ethics pledge that barred him from working on cases involving his former employer Avangrid.

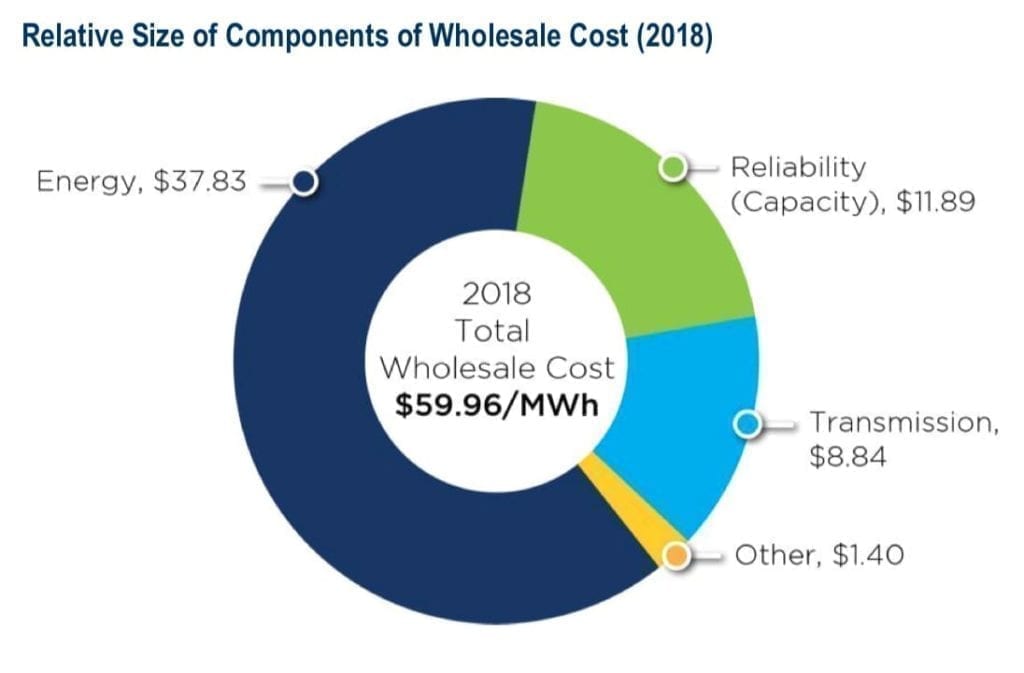

What Is the Minimum Offer Price Rule’s (MOPR’s) Role in PJM’s Markets?PJM operates several types of competitive wholesale markets through which large volumes of power are bought and sold across 13 states and the District of Columbia. Its operations are founded on a mission to provide reliability at the lowest-possible cost, but it also seeks to provide financial incentives to encourage build out of new capacity to ensure reliability. Here’s a brief snapshot of the markets it operates. Energy Market. The largest of PJM’s markets, the energy market makes up about 63% of wholesale power costs, and it operates much like a stock exchange, matching demand for power with offers to provide it in the near term. The energy market is divided into day-ahead and real-time markets, both of which match offers from power suppliers with bids from power consumers. “Day-ahead” essentially describes a forward market, which means prices are set for energy that will be delivered the next day. “Real-time” is a spot market, which means power is procured for immediate delivery. Ancillary Services Markets. These markets help balance power flowing on the grid with customer demand, essentially regulating resources and reserves—which are called ancillary services. Regulation is a reliability product that corrects short-term deficiencies and fluctuations, while reserves are generation resources that can quickly come online. Capacity Market. Making up a much smaller portion of wholesale power cost—about 20%—is the capacity market (also called the reliability pricing model or RPM). As PJM explains, “Capacity is the commitment of resources to deliver electricity or limit electricity demand when they are needed, particularly in an emergency.” Compared to the energy market, which addresses near-term needs, the capacity market prepares for three years into the future to ensure enough supply will be available to meet peak demand—and it has the core function of addressing reliability. Every year, PJM holds a competitive auction (the base residual auction, or BRA) three years before the delivery year to obtain future power supplies at the lowest price. The last one held in May 2018, for example, cleared a total 164 GW of unforced capacity for the period spanning June 2021 to May 2022, representing a 22% reserve margin for PJM’s footprint. “Cleared” generation resources are required to offer power into the energy market for the year they are committed, and importantly, they also commit to serve PJM’s emergency needs whenever called upon.

In 2006, as it introduced the capacity market, or RPM, PJM also established a minimum offer level to operate as a price floor, and it issued the Minimum Offer Price Rule (MOPR) to impose a minimum offer screening process to bar new generators from artificially depressing capacity auction clearing prices through below-cost bids. The current MOPR floor offer price is set as 90% for the applicable net cost of new entry (Net CONE) for the delivery year—which essentially represents the capacity revenue a new generator needs to enter the market. (In April 2019, FERC approved a reduction of the Net CONE, basing it on a newer, more-efficient combustion turbine, and experts suggested the action could further suppress capacity clearing prices.) PJM has traditionally posted Net CONE prices for combustion turbines and combined cycle generators on its website, and it sets Net CONE for nuclear, coal, integrated gasification combined cycle (IGCC), hydroelectric, wind, and solar facilities as $0/MW-Day. For a deeper look at how the MOPR has evolved, read: “A Brief History of the MOPR,” which follows. |

A Brief History of the MOPR

The MOPR evolved out of a settlement PJM reached with participants, and as originally envisioned, it basically set out the relevant conditions for determining when sellers could depress prices below the competitive level in PJM’s capacity auctions. Originally, it did not apply to baseload resources that required more than three years to build (such as nuclear, coal, integrated gasification combined cycle [IGCC] and hydropower plants, or certain upgrades at existing plants). It was mostly focused on all new, non-exempted natural gas-fired resources—and it required those resources to offer at or above the price floor, equal to the net cost of new entry (Net CONE) for the applicable asset class (by generator type and location). Also of note is that the original MOPR exempted planned resources that were being developed in response to a state regulatory or legislative mandate to resolve a projected capacity shortfall.

But the MOPR has since been reshaped by a series of revisions and court battles. In 2011, FERC accepted a PJM proposal to eliminate the state mandate exemption, though it ultimately allowed PJM and its independent market monitor (IMM) to review unit-specific cost justifications for sell offers that fell below the established floor. As part of the 2011 action, FERC ultimately added wind and solar generators to the list of generators—which already included nuclear, coal, IGCC, and hydroelectric resources—that were allowed to offer into the capacity market’s base residual auction at a price of zero.

“As PJM notes, wind and solar resources are a poor choice if a developer’s primary purpose is to suppress capacity market prices,” FERC determined at the time. “Due to the intermittent energy output of wind and solar resources, the capacity value of these resources is only a fraction of the nameplate capacity. This means that wind and solar resources would need to offer as much as eight times the nameplate capacity of a [combustion turbine] or [combined cycle] resource in order to achieve the same price suppression effect.”

In 2013, FERC accepted more categorical exemptions from PJM to address the market effects of new, state-backed natural gas–fired entrants, though it forced the grid operator to retain its unit-specific review process. FERC’s proceeding ultimately revised the MOPR so that it expressly applied only to gas-fired resources—namely combustion turbines and combined cycle resources. But after the D.C. Circuit threw out those changes in July 2017, the MOPR reverted to the 2011 version, essentially requiring all new, non-exempted natural gas-fired resources to offer at or above the default offer price floor (equal to the Net CONE for the resource type) or choose the unit-specific review process. That means, “Because only new, non-exempted natural gas-fired resources are subject to review under PJM’s current MOPR, it permits zero-priced offers by nuclear, coal, integrated gasification combined cycle, wind, solar, and hydroelectric resources,” FERC noted on Thursday.

Since the 2013 action, however, in a dramatic expansion of what began as limited state support for renewable resources, “thousands of megawatts of resources ranging from small solar and wind farms to large nuclear plants” has flooded PJM, as FERC noted Thursday. “In addition, renewable generation targets for state RPS programs continue to increase. Further, state subsidies for capacity resources continue to expand to cover additional resource types based on an ever-widening scope of justifications,” it said.

The trend has alarmed competitive power generators, who have come out forcefully against the MOPR’s application to only some new resources that receive out-of-market subsidies. FERC’s order Thursday, for example, responds directly to two consolidated dockets: a complaint (Docket No. EL16-49-000) filed in March 2016 by several independent power producers, led by Calpine Corp., that alleged the MOPR is unjust and unreasonable because it creates incentives for noncompetitive offers and may prevent the exit of uneconomic resources; and a second proceeding (Docket Nos. ER18-1314-000, et al.) in which PJM filed two alternate proposals to revise its tariff under section 205 of the Federal Power Act (FPA) to address the price suppressing effects of state out-of-market support for certain resources.

In one of the two April 2018–submitted proposals, PJM sought to expand the existing MOPR to apply to any generation resource that receives subsidies, with exemptions. The so-called “MOPR-Ex” approach sought to extend the geographic reach of the MOPR to apply to external capacity resources as well as internal capacity resources, without a resource size threshold.

In June 2018, however, FERC issued its ground-shaking order, which effectively amplified market uncertainty. In that order, though it agreed with the IPPs that the existing tariff wasn’t fair and failed to protect the integrity of competition in the capacity market, it rejected both of PJM’s alternative proposals because PJM did not demonstrate they were “just and reasonable, and not unduly discriminatory or preferential.”

PJM ultimately filed two new approaches on Oct. 2, 2018, that it said were designed to recognize a state’s authority to shape the makeup of its generation fleet. The first involves a coupling of MOPR-ex and a Resource Carve-Out (RCO) construct. The RCO sought to give states the alternative to remove state-subsidized generation assets (which are subject to MOPR) from the capacity market. The RCO would then allow subsidized resources to obtain a capacity commitment without having to clear the capacity market. In the second option, which PJM called an “extended RCO,” PJM sought to combine the RCO with a mechanism to restore the market clearing price to the most economic, “correct” competitive level. The extended RCO would also include price formation rules to thwart price suppression, which could result if the RCO stood alone.

What Does the Dec. 19 Order Do?

Last week, FERC essentially reversed its disdain for the MOPR-Ex approach, adopting it over the RCO and extended RCO because “FERC determined that those proposals would unacceptably distort the markets, inhibiting incentives for competitive investment in the PJM market over the long term,” it said in a statement.

Fundamentally, the order means PJM will now have 90 days—until March 18, 2020—to expand its current MOPR, which requires review of new natural gas–fired resources, to apply to both new and existing resources, internal and external, that receive (or are entitled to receive) certain out-of-market payments—unless an exemption applies. “Going forward, the default offer price floor for applicable new resources will be the Net Cost of New Entry (Net CONE) for their resource class; the default offer price floor for applicable existing resources will be the Net Avoidable Cost Rate (Net ACR) for their resource class,” it said.

The replacement rate’s exemptions, however, include a long list that reflect prior FERC actions: existing self-supply resources; existing renewable resources that now participate in state RPS programs; and existing demand response, energy efficiency, and storage resources. Exemptions also include new and existing competitive resources that are not subsidized (which is why they don’t generally require review). Significantly, in a bid to “preserve” flexibility, FERC also added new and existing suppliers that don’t qualify for a categorical exemption to justify a competitive offer below the price floor through a unit-specific exemption.

“Collectively, these exemptions underscore our general intent that most existing resources that have already cleared a capacity auction, particularly those resources the Commission has affirmatively exempted in prior orders, will continue to be exempt from review,” FERC explained. “Similarly, new resources that certify to PJM that they will not receive out-of-market payments will generally be exempt from review through the Competitive Exemption, with the exception of new gas-fired resources, which were already subject to review under the current MOPR and will remain so under the replacement rate.”

Also of note is guidance regarding exemptions in which FERC stressed that a new or existing resource that does not otherwise qualify for an exemption may seek a unit-specific exemption. It also noted that the expanded MOPR only applies to resources subsidized by states—not to federally subsidized resources.

What Happens Now?

FERC gave PJM until mid-March 2020 to submit a compliance filing, as well as to provide revised dates and timelines for the 2019 Base Residual Auction and related incremental auctions, as well as revised timelines for the May 2020 auctions.

In a statement to POWER on Friday, PJM said it was reviewing the order. “As we prepare our compliance filing, we will engage with our stakeholders and members to discuss the substance of the order and its impact beginning at the Jan. 8 Market Implementation Committee meeting,” it said.

Over the short term, at least, as a variety of legal experts told POWER, a rehearing on the issue is highly likely. In last week’s order, FERC itself acknowledged it hadn’t tied up the issue neatly. “[T]his replacement rate does not purport to solve every practical or theoretical flaw in the PJM capacity market asserted by parties in these consolidated proceedings, or in related proceedings,” it said. “There continue to be stark divisions among stakeholders about various issues that we cannot resolve on this record.” FERC’s key aim, it said, was to concentrate on the core problem presented in the Calpine complaint and in PJM’s April 2018 rate proposal—“that is, the manner in which subsidized resources distort prices in a capacity market that relies on competitive auctions to set just and reasonable rates.”

FERC Chairman Neil Chatterjee in a statement last week sounded almost apologetic. “I recognize, and wholeheartedly respect and support, states’ exclusive authority to make choices about the types of generation they support and that get built to serve their communities. They still can do so under this order,” he said.

Why Is It Such a Deeply Divisive Issue?

A sharply worded dissent—which spans 28 pages—authored by Commissioner Richard Glick, the only voting Democrat, perhaps best describes how contentious the issue has grown. “From the beginning, this proceeding has been about two things: Dramatically increasing the price of capacity in PJM and slowing the region’s transition to a clean energy future,” Glick alleged in his opening. “It is a bailout, plain and simple.”

Glick has pushed for giving regional markets a reasonable pathway to accommodate state policies. At the National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners’ (NARUC’s) annual meeting in San Antonio this November, for example, he told the group’s former president, Nick Wagner, that if FERC blocked the flood of subsidized generation in PJM and other wholesale electric markets, it would be “short-sighted.” In his dissent, he said FERC, which had “bungled the proceeding from the beginning,” provided “almost no guidance,” yet it gave PJM only 90 days to work out the changes “that go to the very heart of its basic market design.”

At the core of Glick’s objections about the order was its “sweeping” definition of “subsidy,” which he said could subject “much, if not most, of the PJM capacity market to a [MOPR].” He also took issue with the vast reach of the exemptions, which he said “will have the principal effect of entrenching the current resource mix by excluding several classes of existing resources from mitigation.” And finally, the order “unceremoniously discards the so-called ‘resource-specific FFR [fixed resource requirement] Alternative,’ which had been the crux of the Commission’s proposal in the June 2018 Order that sent us down the current path.” The FRR Alternative, he noted, was the one “fig leaf” that FERC extended to state authority in its June 2018 order, and without it, the capacity market would likely “culminate in a system of administrative pricing that bears all the inefficiencies of cost-of-service regulation, without any of the benefits.”

The order’s effect would be far-reaching, he warned. It would increase capacity prices in PJM’s base residual auction—causing rates to surge for PJM customers—as well as increase PJM’s “already extensive quantity of redundant capacity.” It would also “ossify the current resource mix,” because it “is carefully calibrated to give existing resources a leg up over new entrants and to force states to bear enormous costs for exercising the authority Congress reserved to the states when it enacted the Federal Power Act (FPA),” Glick said.

“We all know what is going on here: The costs imposed by today’s order and the ubiquitous preferences given to existing resources are a transparent attempt to handicap those state actions and slow—or maybe even stop—the transition to a clean energy future,” said Glick.

Reactions from industry, however, were mixed. While competitive generators generally lauded the decision, public power producers lambasted it, saying it threatened their core business model. Trade groups that separately represent coal, nuclear, wind, and solar generators also pointed to specific issues that could stymy their businesses. See an in-depth analysis of industry reactions here: “Mixed Reactions to FERC’s Recent MOPR Order from Power Generators.”

| Read POWER’s in-depth coverage of the MOPR issue here:

Mixed Reactions to FERC’s Recent MOPR Order from Power Generators (December 2019) FERC Nixes PJM’s Fixes for Capacity Market Besieged by Subsidized Resources (July 2018)States to FERC: Promote Market Designs That Recognize State Priorities (October 2019) |

—Sonal Patel is a POWER senior associate editor (@sonalcpatel, @POWERmagazine)