The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) on Tuesday proposed its first-ever carbon pollution standard for new power plants, limiting carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from new fossil fuel-fired power plants to 1,000 pounds/MWh. The standard is achievable for new natural gas combined cycle units without add-on controls, but it would force new coal or petroleum coke units to install carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology, which is currently commercially unavailable, the agency acknowledged.

The proposed standard applies only to new gas and coal generating units that are larger than 25 MW. It would not apply to existing units, including those undertaking modifications to meet other air pollution standards, nor to new power plant units that have permits and start construction within 12 months of this proposal. It also would not apply to units in Hawaii and the territories, or to units looking to renew permits as part of a Department of Energy (DOE) demonstration project, provided that those units start construction within 12 months of the proposal.

“We have no plans to address existing plants and in the future, if we were to propose a standard, it would be informed by an extensive public process with all the stakeholders involved,” EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson told reporters on a conference call on Tuesday.

The EPA’s proposed standard reflects the "ongoing trend in the power sector to build cleaner plants, including new, clean?burning, efficient natural gas generation, which is already the technology of choice for new and planned power plants," the agency said. It is also in line with state efforts, such as those implemented in Washington, Oregon, and California, which limit greenhouse gas "pollution," and Montana and Illinois, which require CCS for new coal generation.

"New natural gas combined cycle (NGCC) power plant units should be able to meet the proposed standard without add?on controls," the agency said. "In fact, based on available data, EPA believes that nearly all (95%) of the NGCC units built recently (since 2005) would meet the standard."

For new coal units, which will be required to use CCS or other carbon-mitigating technologies, the agency proposes a compliance option to use a 30-year-average of CO2 emissions to meet the proposed standard, rather than meeting the annual standard each year.

For new coal units, which will be required to use CCS or other carbon-mitigating technologies, the agency proposes a compliance option to use a 30-year-average of CO2 emissions to meet the proposed standard, rather than meeting the annual standard each year. “To the extent market participants have alternative views of both the cost and development of CCS, new conventional coal-fired capacity (or [integrated gasification combined cycle (IGCC)] could be built and operated for some time, with the intention to apply CCS with high removal efficiency at some later date, in order to achieve the required average rate over the 30 year period,” the EPA said.

EPA: CCS Is the “Technology of Choice”

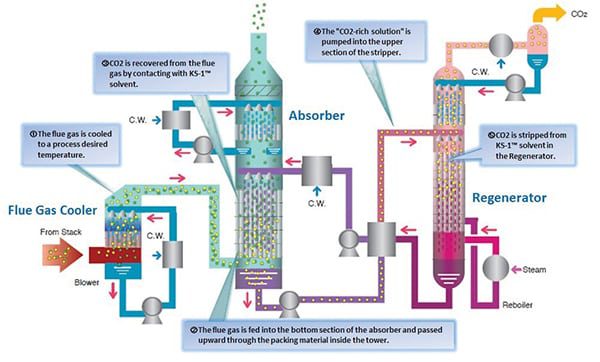

“Carbon Capture and Storage would be the technology of choice; however there are a range of technologies that could be used on both the capture and sequestration side,” EPA spokesperson Cathy Milbourn told POWERnews.

“On the sequestration side, it could range from using captured CO2 for purposes like enhanced oil recovery (which is currently being done in numerous sites across the U.S.) to dedicated sequestration. On the capture side, it can be done using IGCC technology, more traditional pulverized coal technology with post-combustion capture or oxy-combustion with post-combustion capture.”

Some projects in the U.S. have already shown carbon capture gains, Milbourn said, pointing to AES’s coal-fired Warrior Run and Shady Point power plants in Cumberland, Md., and Panama, Okla., which are both equipped with amine scrubbers developed by ABB/Lummus. At Warrior Run, about 110,000 metric tons of CO2 are captured per year, and 66,000 metric tons are captured annually at Shady Point for use in the food processing industry. The EPA also noted American Electric Power’s now-defunct pilot-scale CCS project at Mountaineer using Alstom’s chilled ammonia process, and Southern Co.’s ongoing Alabama Power Plant Barry demonstration project to capture 150,000 metric tons of CO2 annually.

According to the National Energy Technology Laboratory, which tracks existing and proposed U.S. coal-fired power projects, in 2011, five new coal plants totaling 2,343 MW were commissioned. At least 10 other coal plants with a total capacity of 6,619 MW were under construction, and a 320-MW project had obtained all permits and was nearing construction.

Meanwhile, at least 13 plants with a capacity of 8,934 MW were in the permitting phase, and 36 announced projects (11,871 MW) were in the early stages of development. Of the plants that were under construction, permitted, or nearing construction as of January 2012, four had proposed to use pulverized coal subcritical technology; six opted for circulating fluidized bed technology, seven would use supercritical technology, and seven others, IGCC. In comparison, seven announced projects proposed to use subcritical technology while 11 were announced IGCC plants.

CCS could potentially reconcile the widespread use of coal with the need to reduce carbon emissions, but that could be decades away, suggests the International Energy Agency in its November-released World Energy Outlook. "The demonstration phase, which is only just beginning, is likely to last for a decade." At the end of 2010, a total of 234 active or planned CCS projects had been identified, but only five of these demonstrated the full range of capture, transport, and permanent storage of CO2.

Challenges to full-scale demonstration and commercial deployment include high construction costs (assuming an average project cost for a CCS plant of $3,800/kW equates to around $2 billion for a 500-MW plant) and difficulties in financing large-scale projects. "The likelihood is that there will be, at best, no more than a dozen large-scale demonstration plants in operation by 2020," the agency projects.

Asked what carbon-mitigating technologies developers of coal-fired plants could install until CCS becomes commercially feasible—beyond costly precombustion and post-combustion capture technologies—the EPA pointed to “many small actions that can be undertaken, which, cumulatively, can result in notable efficiency improvements.” These include, it said, regular maintenance to sustain optimal operation conditions, maintaining furnace operations near peak efficiency, and ensuring furnace soot removal systems are functioning properly.

Otherwise, generators could switch to “lower-emitting fuels, increased generation share from lower-emitting sources, decreased loss of power via transmission and distribution systems, and improved end-use efficiency lowering electricity demand for the same level of service provided.”

No “Notable Costs”

According to the EPA, the new carbon standard for power plants is “in line” with sector investment patterns, which is why the proposed standard is not expected to have “notable costs” or impact reliability. "EPA, [the Energy Information Administration], and industry projections indicate that, due to the economics of coal and natural gas among other factors, new power plants that are built in the near future will already meet these proposed standards," Milbourn told POWERnews. "Therefore, EPA estimates that there are no additional costs or benefits associated with this proposed rule."

Milbourn pointed to the EPA’s Regulatory Impact Analysis, which says that "even in a baseline scenario without the proposed rule, the only capacity additions subject to this rule projected during the analysis period (through 2020) are compliant with the requirements of this rule (e.g., combined cycle natural gas and small amounts of coal with CCS supported by DOE funding)."

The analysis also says, however, that research into cost and efficiency of varying levels of capture relative to building other energy technologies indicates that lower levels of carbon capture at new coal facilities could be cost competitive, and the costs of meeting the proposed emission rate immediately could be achievable.

"For example, The Clean Air Task Force has compiled data that indicates the levelized cost of electricity for a new supercritical pulverized coal unit with 50 percent CCS (or 1,080 lb/MWh CO2, which is just above the proposed standard) could be $116/MWh compared to $147/MWh for 90 percent removal," it says. "However, investment decisions will be made on a case by case basis dependent upon a number of factors, all of which are difficult to estimate in advance."

An Achievable Rule?

Industry experts generally agree that the rule is unachievable by any coal-fired power plant, absent application of currently unavailable carbon sequestration technology. As Adam Kushner, partner in law firm Hogan Lovells’ Environmental practice and former director of the Office of Civil Enforcement at the EPA, told POWERnews, “EPA’s preamble effectively acknowledges that carbon capture and storage (CCS) is generally not available today. It is for that reason EPA established an emission limit based on a 30-year compliance averaging period. That is, EPA will give new coal plants 30 years to demonstrate they can meet the proposed standard, since the proposed numeric emission limitation for coal-fired power plants is based on a standard currently only achievable by combined cycle natural gas plants,” he said.

“In the preamble to the rule, EPA specifically states that it anticipates that the only way new coal-fired power plants can meet the standard is by carbon capture and storage (CCS) of approximately 50% of the CO2 in the plant’s exhaust gas during start-up or through more effective CCS as it is developed down the road.”

Perhaps the foremost implication of the rule is that it will “effectively halt the construction of new coal-fired power plants. Moreover, the effect of the rule, given the historic low price for natural gas, will be to provide further incentive for coal-fired power owners and operators to continue the trend of converting coal plants to natural gas,” Kushner added.

But the proposed rule won’t be finalized without hiccups, he noted. “EPA will face significant legal challenges to the rule.”

As required by the Clean Air Act for new source performance standards (NSPS) rules, the EPA will need to establish that the emission limit in the rule is “achievable through the application of the best system of emission reduction which . . . has been adequately demonstrated.” For that reason, the “EPA may be hard pressed to show that CCS is adequately demonstrated given its unavailability to many coal-fired power plants. In the face of that specific challenge, EPA will need to justify its reliance on a 30-year compliance standard, which suggests in and of itself that such technology is generally not available today. EPA is also likely to face challenges for predicating the proposed emission standard for coal-fired units on an emission standard EPA acknowledges can only currently be achievable by combined cycle natural gas units.”

Kushner said that several cases related to the EPA’s regulation of greenhouse gases were already being legally challenged. Among these are cases recently argued and fully submitted to the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, which challenge, among other things, the EPA’s finding that greenhouse gases threaten the public health and welfare of current and future generations, and the EPA’s “Tailoring” rule, which applies the Clean Air Act’s prevention of significant deterioration (PSD) program to greenhouse gas emissions emitted from both new and existing coal-fired power plants.

“The challenges that are ensuing in the D.C. Circuit will not necessarily impact the proposed NSPS for new plants. However, should the D.C. Circuit reject challenges to the EPA tailoring rule (which is currently in effect), and should EPA’s proposed NSPS be adopted as a final rule, then any PSD permits issued for new plants will have to include an emission limit that is not less stringent than the emission limit in the proposed NSPS for new coal-fired power plants,” Kushner said.

The EPA will accept comment on this proposed rule for 60 days following publication in the Federal Register.

Sources: POWERnews, EPA, Hogan Lovells, Pace Law school, IEA