For the first time in decades, a wave of nuclear projects across the U.S. is advancing in parallel—from test reactors to early construction. POWER examines how first movers are navigating execution risk, supply chain constraints, and the race to achieve criticality by 2026.

For the first time since the 1970s, multiple nuclear projects are under simultaneous construction in the U.S. Between now and July 4, 2026, nearly a dozen companies have set out to achieve criticality at authorized test sites in Idaho, Tennessee, Texas, Wyoming, Kansas, and Utah—a milestone that, in recent history, might have taken a decade to accomplish. Alongside these demonstration reactors, two first-of-a-kind commercial advanced reactor projects are advancing toward deployment by decade’s end.

In Tennessee, after a series of regulatory triumphs, Kairos Power has begun pouring nuclear-related concrete and executing site works at Oak Ridge for its Hermes demonstration reactors. A key facet of the company’s iterative fluoride salt–cooled design strategy, the engineering will ultimately anchor a commercial partnership with Google that targets up to 500 MW of clean power deployment between 2030 and 2035.

In Texas, X-energy’s Xe-100 high-temperature gas-cooled (HTGR) reactors are entering site preparation and early project execution at Long Mott Energy’s pioneering industrial power facility, a project that will scaffold a stunning fleet expansion beyond Dow’s four-unit Seadrift Operations, including the Amazon-backed 12-unit Cascade Advanced Energy Facility in Washington, and a 6-GW fleet planned with UK firm Centrica.

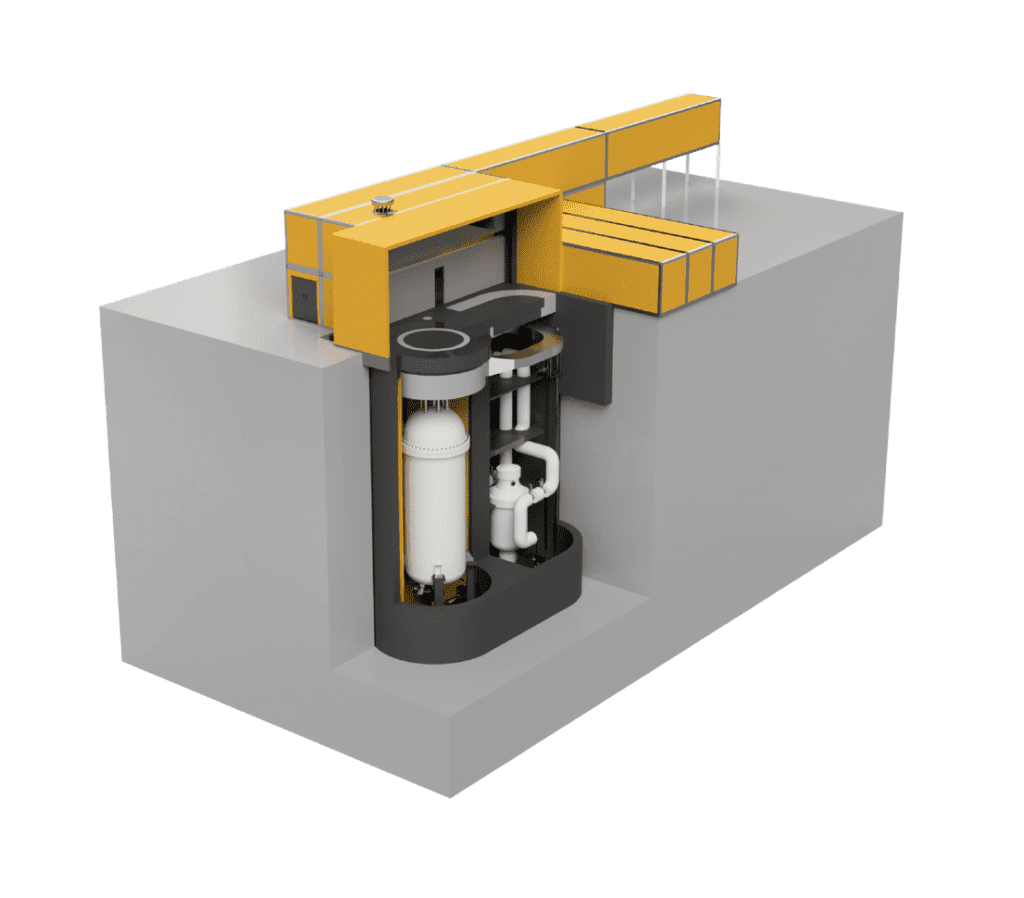

And in Wyoming, TerraPower’s Kemmerer 1 Natrium project (Figure 1) has moved decisively from planning into early physical construction, with site works underway and long-lead procurement accelerating (see sidebar: “Q&A: Chris Levesque on TerraPower’s Path to First-of-a-Kind Execution”). The company has filed its combined operating license application and is deploying capital at scale—raising more than $500 million during 2025 alone—to lock in manufacturing slots and secure supply chain commitments. Natrium, distinctive as it is revolutionary, will pair the 345-MWe sodium-cooled fast reactor with molten-salt energy storage, setting the stage for an innovative load-following asset.

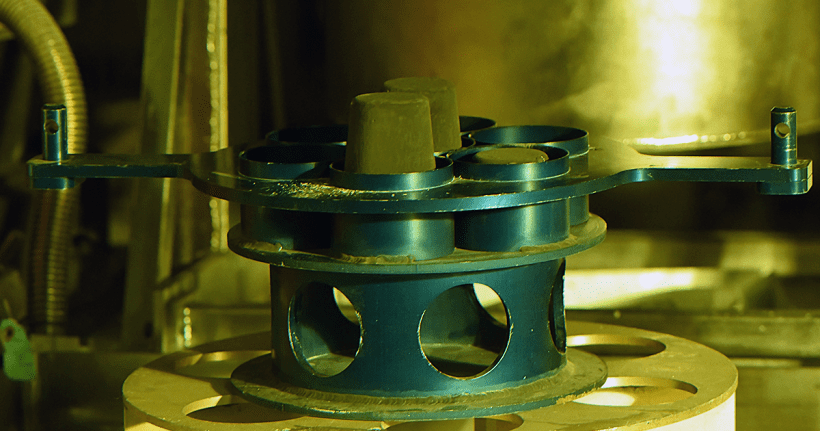

Q&A: Chris Levesque on TerraPower’s Path to First-of-a-Kind ExecutionTerraPower’s Natrium reactor represents perhaps the most advanced first-of-a-kind nuclear project under construction in the U.S. With a Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) construction permit expected imminently, fuel loading planned for 2030, and commercial operation targeted for 2031, the company is now gearing up to translate its advanced reactor innovation into disciplined, repeatable execution at scale. To understand how TerraPower moved from concept to real-world project delivery—and what it reveals about the broader nuclear renaissance—POWER spoke with Chris Levesque (Figure 2), the company’s president and CEO, in January 2026. The conversation ranged from how the company transformed its culture as it moved from research and development (R&D) into execution, to the fuel supply strategy that emerged after Russia became an untenable source, to the Meta agreement that will test whether Natrium can scale from a single demonstration into a commercial fleet of up to eight units. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity; questions and responses reflect the substance of a longer discussion.)  POWER: TerraPower began with a formidable team of PhDs focused on fundamental physics. How did the company’s approach evolve as you moved from design to execution? Levesque: It was critical that Bill Gates and the founders realized innovation was necessary. In the nuclear industry I grew up in, you were told, “Don’t do anything new, just do what was done last time.” That raised capacity factors and made the industry very safe, but if you do that for 30 or 40 years, you miss opportunities to employ advanced computing and advanced materials. In our early years, we designed a reactor that wasn’t limited by what’s been done before—it was limited by what science allows. You might go into a conference room and see multivariate calculus on the board, because we asked, “What does nature allow?” But as you move from R&D across the valley of death and engage the supply chain and constructor, you have to convey things in their terms. With Bechtel, there was a realization that our plant consumes far less concrete, steel, and labor—leading to lower costs. That’s what will let future Natrium plants be built in 36 months, when today’s light-water reactors take 10 years or more. We’ve moved from talking about Navier-Stokes equations to asking, “How many tons of concrete do we need to pour per day?” Our team went from 40% PhDs to 20%. Some folks left to go back to national labs because they wanted to remain ideas people. But when you get into execution and things don’t go right, it’s great to reach back to people who know the governing equations—so you can use physics to solve problems, not just ask how someone fixed it last time. POWER: How did you approach the regulatory process, given both the technical novelty and the evolving regulatory framework? Levesque: Even before we talk about regulation, it starts with a strong belief that we’re building a very safe nuclear reactor. If we’re going to have nuclear energy all over the world—in Africa, Indonesia—we really need Generation IV plants that are at the next level of safety. Plants that in a Fukushima scenario will cool themselves naturally with absolutely no human interaction. Today’s plants are very safe in the U.S. and Europe, but Gen IV reactors are something like 1,000 times safer probabilistically. For us, the experience with the regulator began with communication—not just submitting our application and letting them process it, but multiple training sessions with the NRC and Wyoming regulators on the Kemmerer Unit 1 construction permit application. We were the first to employ the Licensing Modernization Project. When we submitted our 14,000-page application in March 2024, that was the culmination of years of pre-application engagement. The process has gone really well as a result. The NRC already issued the safety evaluation, and we expect to receive the construction permit in the coming weeks. POWER: High-assay low-enriched uranium (HALEU) fuel availability delayed the project by two years. How are you de-risking fuel supply and other critical components for a multi-billion-dollar project? Levesque: Even before de-risking, we had to create capabilities that didn’t exist. There was no HALEU enrichment in the U.S. When the war started four years ago, we made the decision not to utilize Russian fuel—for business reasons and public acceptance reasons. We recognized that ASP Isotopes in South Africa had this capability, and we’re procuring HALEU from them. We made an investment and did serious technical due diligence. They’re progressing and will support our schedule. For metalization, these processes existed around the world, but nothing recently on the commercial side. With just private investor money—no DOE [U.S. Department of Energy] money—we contracted with Framatome to pilot the metalization line in Richland, Washington. We recently publicized production of the first uranium metal pucks. Eventually, those pucks will be extruded into fuel rods. We do need multiple paths. That’s why we’re encouraging DOE to award grants under the HALEU Availability Program. DOE has been given over $3 billion by Congress to invest in American LEU and HALEU production. We have a plan we’re managing closely for the first core load for Kemmerer in 2030, but we’re going to follow the first plant quickly with scale-up. We need lots of capacity and a diverse supply chain. We’ve invested in one fuel manufacturing facility with Global Nuclear Fuel in North Carolina, but as we deliver additional units, we’ll need to expand that industrial capacity. Bill Gates always asks me two things: how we stay on time for the first unit, and how fast can we scale. Just last week at Davos, he met with HD Hyundai’s chairman about scaling up to build multiple Natrium reactors per year at their facility in Korea. POWER: The Meta agreement announced in January calls for up to eight Natrium units. What’s the biggest execution risk in scaling from a single unit to fleet deployment? Levesque: If you think of typical challenges—regulatory risk is well in hand. We’re about to get a construction license early. That’s a really new story for nuclear. Long schedule durations? For us, it begins with less steel, less concrete, less labor. That’s how you have a faster schedule. We’re in the phase with Bechtel where we really understand those quantities and can validate an aggressive schedule. My biggest concern is labor and supply chain. We haven’t been building plants in the U.S., so we don’t have enough craft labor. It’s important that Natrium consumes less labor—that’s part of solving it. But mobilizing many reactors simultaneously requires tens of thousands of workers. We talk with DOE about how to manage this. University presidents come to us wanting to discuss PhD programs. I try to pivot them: “Can we talk about your work with community colleges on apprentice programs for welders and electricians?” For supply chain, the few reactors built in the free world have been done one at a time, as a project, not a product. We really need to think about continuous flow manufacturing. HD Hyundai makes over 50 ships a year, so they have this operating model down. That’s why we’re working with them on our reactor enclosure system. POWER: Natrium pairs a sodium reactor with molten-salt energy storage—a distinctive innovation. How has this shaped your business model as the power industry evolved? Levesque: About six years ago, we were hearing from multiple utilities that it would be great if we could load-follow. Even though nuclear had been baseload, utilities were saying this because of renewables on the grid. Large gigawatt-scale light-water reactors have limitations in how quickly they can change power. We had this innovation where we realized we could keep our reactor running at the same power all the time, but use molten salt tanks like a thermal battery to flex our power. The 345-MW plant can vary its output up to 500 MW for five hours. A big collateral benefit we didn’t realize at first: by placing the molten salt tanks between the turbine and the nuclear island, we decoupled the whole secondary plant from the reactor. We made a case to the NRC that our whole energy island—the molten salt tanks and turbine—is non-nuclear. So, when we procure those components and build that part of the plant, it’s done with non-nuclear controls. The paradigm was that the NRC oversees everything onsite. For Natrium, really only about a third of the plant is under NRC cognizance. About two-thirds of Kemmerer is under Wyoming’s cognizance. That was a pretty big regulatory breakthrough as well. POWER: What advice would you give other advanced nuclear developers navigating today’s opportunities and uncertainties? Levesque: At a macro level, we can see the electricity demand. Nuclear has a great story—small land area, small consumption of materials. Multiple technologies make sense. It’s really going to be about putting together delivery teams. This is hugely capital intensive, not a business for the faint of heart. Did we need regulatory changes? Yes, we’ve been supportive. But you should really prioritize communication with communities and the regulator over a speedy process. That approach has worked for us and will lead to a faster approval in the end. It’ll also help with subsequent plants. As we look at the UK and South Korea, we already have significant engagement with regulators. We want to show them the rigor we went through with the NRC. That’s super important. If you’re focused on safety and rigor, you shouldn’t have to worry about expediting the regulator. |

While these projects represent the first wave of groundbreakers, they are the first excavations in ground that has not been worked in half a century. For an industry long stalled by cost overruns, licensing drag, and broken construction continuity, they herald a decisive break from the past. But they also reveal a broader national expansion already underway. Alongside advanced reactor demonstrations, feasible prospects through 2030 include microreactors for defense and remote power, the fiercely defended restart of shuttered commercial plants, and fresh optimism, or at least solid renewed consideration, of a new fleet—of up to 10—large, grid-scale reactors.

As Nuclear Energy Institute (NEI) President Maria Korsnick noted during a Congressional hearing in January, for now, industry expects to invest roughly $22 billion to optimize and expand its current fleet. Plant owners are pursuing license renewals at 26 units, power uprates at 29 units, and extended fuel cycles at another 12 reactors facilitated by accident-tolerant fuel programs, she noted. “By making even greater use of existing assets,” Korsnick told lawmakers, “the industry will add more than 8 GW of additional nuclear capacity.”

However, that work is unfolding with efforts to expand the nation’s nuclear capacity. Signaling industry’s confidence in new nuclear, NEI member utilities report approximately 23.4 GW of new nuclear capacity under active planning over the next 15 years. “To ensure new deployments are constructed in a timely and cost-effective manner, the industry is applying construction and project-management best practices to improve schedule discipline, enable repeatability, and significantly reduce costs as deployment expands,” she said.

Why Innovation Became Inevitable

In some ways, as experts have explained to POWER, the breaking of new ground across the global nuclear sector has been a delayed consequence of forces already in motion. In 2020, POWER reported on the industry’s quest for reinvention, as it grappled with multiple factors, including an aging fleet, market forces, and policy pressures. At the time, the shift felt incremental. But in 2026, it looks inevitable.

“This moment differs from past nuclear ‘renaissances’ in fundamental ways,” Idaho National Laboratory (INL) Director Dr. John Wagner explained to lawmakers in January. “Historic energy demand growth driven by data centers and artificial intelligence (AI) infrastructure, unprecedented private-sector investment flowing into nuclear technologies, the emergence of new innovative reactor developers, and critical national security needs requiring reliable baseload power have converged with bipartisan Congressional support and a federal commitment to removing decades of regulatory barriers,” he said.“For the first time in decades, market forces, national security imperatives, and federal policy have aligned. The question is no longer whether America needs nuclear energy, but how much, how quickly, and how to make it happen.”

The urgency is underscored by an interesting interplay of geopolitical factors, Wagner noted. China and Russia now dominate global nuclear construction, accounting for roughly 94% of reactors under construction worldwide, while U.S. deployment has remained largely stalled for nearly four decades, aside from the long-delayed completion of Vogtle Units 3 and 4 in Georgia. And while China alone has more than 30 reactors under construction, Russia’s state-owned Rosatom is building units across multiple foreign markets, pairing construction with export models designed to lock in long-term influence. “We must reclaim nuclear leadership,” Wagner said, warning that nuclear technology has become a strategic asset shaping energy security, industrial competitiveness, and global standards for decades to come.

The Biggest Lever: Policy

In February 2025, adding to a substantial bipartisan buildup (including from previous administrations) championing new nuclear power, the Trump administration outlined an ambitious goal to make nuclear a “pillar of American dominance.” Pivotally, it set out an imperative to expand from 100 GW of nuclear capacity to 400 GW by 2050. It followed that policy in quick succession in May 2025 with four sweeping executive orders that addressed several longstanding systemic barriers (see sidebar: “The 2025 Executive Orders That Transformed Nuclear’s Trajectory”). These, for example, include regulatory delays that have historically stretched licensing to five years or more, fuel supply vulnerabilities that foster a dependence on foreign enrichment services, and the absence of a coherent federal framework for siting advanced reactors on public lands.

The 2025 Executive Orders That Transformed Nuclear’s TrajectoryIn May 2025, President Trump signed four executive orders that seek to quadruple U.S. nuclear capacity by 2050—from 100 GW to 400 GW—through fuel security, regulatory reform, accelerated testing, and national security deployments. EO 14302: Reinvigorating the Nuclear Industrial Base

EO 14300: Reforming the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC)

EO 14301: Modernizing DOE Reactor Testing

EO 14299: Deploying Advanced Nuclear for National Security

At the American Nuclear Society’s Winter Conference in November 2025, while experts generally acknowledged that the four orders represent an unprecedented alignment of policy, capital, and customer demand, they pointed to several nuanced considerations. First, panelists stressed that nuclear fuel supply is strategically existential. Because the U.S. now relies on imports for roughly 99% of its enrichment, private fuel-cycle investments—such as new domestic enrichment capacity—must ramp in parallel with reactor deployment, potentially creating a significant coordination challenge between government policy, utilities, and suppliers. Second, while cultural transformation at the NRC is underway, reforms will only succeed if its unprecedented collaboration with DOE and industry firmly embraces that safety and efficiency can genuinely coexist, so that faster processes are seen as disciplined and risk-informed rather than less rigorous, they said. Third, panelists warned that execution capacity—not intent—may be the binding constraint. While executive order–driven targets such as first criticality by July 4, 2026, are real, even if highly aggressive, they assume timely fuel delivery, DOE authorizations, NRC alignment, and on‑schedule construction from a still‑immature supply chain. Success will require DOE, the national labs, and vendors to sustain “concierge‑style” project ownership, iterate rapidly on first‑of‑a‑kind builds, and avoid treating the pilot program as a one‑off victory rather than the start of a repeatable, scalable deployment model, experts suggested. And finally, experts generally were optimistic that the Department of War’s commitment to programs like Project Janus—the Army’s new microreactor program of record, which is built on a NASA‑style, milestone‑based model with multiple vendors and up to nine initial bases—could break the first‑mover problem. By designating an executive agent, funding milestones, and sharing first‑reactor risk in partnership with DOE, Idaho National Laboratory, and the Defense Innovation Unit (the Pentagon’s rapid-procurement arm for commercial technology), the Pentagon is giving vendors confidence that successful demonstrations will unlock subsequent commercial orders—and that could create a market flywheel that transcends government procurements. |

The orders build on progress already established by past Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Nuclear Energy efforts to deploy first-of-a-kind nuclear technologies, including its Advanced Reactor Demonstration Program (ARDP), under which several awardees—notably TerraPower’s Natrium and X-energy’s Long Mott project—have completed critical design milestones and attracted substantial private investment. In tandem, the DOE has continued to advance Biden-era programs, including the Generation III+ Small Modular Reactor Program, the Demonstration of Operational Microreactor Experiments (DOME), and ongoing efforts to support fuel qualification, materials testing, and spent fuel recycling across the national laboratories.

In December 2025, the department awarded up to $800 million in cost-shared funding under its Generation III+ Small Modular Reactor Program to Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) and Holtec Government Services, supporting TVA’s GE Vernova Hitachi BWRX-300 project at the Clinch River site in Tennessee and Holtec’s planned SMR-300 deployment at the Palisades site in Michigan. Earlier, in July 2025, the DOE made its first conditional selections for testing at the DOME facility at INL, choosing Radiant Nuclear’s Kaleidos reactor and Westinghouse’s eVinci design for fueled experiments in the repurposed Experimental Breeder Reactor II containment. Testing is slated to begin as early as spring 2026, and additional application rounds are planned annually. The May executive orders, meanwhile, have kick-started new initiatives, most notably the Reactor Pilot Program, the Fuel Line Pilot Program, and the DOE’s updated authorization process.

Finally, and as significantly, the DOE’s financing office—now called the Office of Energy Dominance Financing (EDF)—has implemented a range of commercialization initiatives. In November, Energy Secretary Chris Wright suggested nuclear would be the primary beneficiary of that authority. “I think the strong pull of AI for more electricity is going to bring billions of dollars of equity capital in from very creditworthy providers. And then that’ll be matched three to one, maybe even up to four to one with low-cost debt, dollars from the Loan Programs Office,” he said.

Regulatory Momentum and Roadblocks

For now, the DOE’s work builds on nearly a decade of bipartisan Congressional groundwork, a foundation that began in 2018 with passage of the Nuclear Energy Innovation and Modernization Act (NEIMA) and the Nuclear Energy Innovation Capabilities Act (NEICA), continued through the Energy Policy Act of 2020’s provisions to address fuel availability and commercialization, and culminated in the Accelerating Deployment of Versatile, Advanced Nuclear for Clean Energy (ADVANCE) Act of July 2024, which mandates a sweeping modernization of NRC licensing timelines and processes.

In parallel, Congress has appropriated $3.4 billion to strengthen domestic nuclear fuel supply chains through the HALEU (high-assay low-enriched uranium) Availability Program as a response to vulnerabilities laid bare by Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine and to the lingering reliance on Russia as the sole commercial supplier of HALEU required by many advanced reactor designs.

The measures have been pivotal for first movers, noted Nuclear Innovation Alliance President Judi Greenwald. Over the past five years, the NRC has made licensing “more risk-informed, performance-based, technology-inclusive, and efficient,” progress driven less by abstract rulemaking than by “more than a dozen advanced reactor developers engaging one-on-one with the NRC under existing rules,” she said. For example, while Kairos Power’s pioneering Hermes 1 construction permit took roughly two years, Hermes 2 was approved in 16 months with 60% fewer NRC resources (Figure 3). TerraPower’s Natrium review was completed in 18 months—nine months faster than initially estimated and under budget, and NuScale’s US460 design approval came in two months early and 13% below cost. The NRC now estimates construction permit reviews of 18 months for X-energy’s Long Mott project in Texas and 17 months for TVA’s Clinch River BWRX-300.

And beyond schedule compression, Greenwald pointed to structural reforms that lower execution risk across the entire pipeline. Under the ADVANCE Act, the NRC finalized licensing fee reform effective October 2025, cutting hourly fees for advanced reactor applicants by more than 50%, extended reactor design certifications from 15 to 40 years to support repeat deployment, and adopted a risk-informed approach to right-sizing emergency planning zones, steps that she said reduce cost, improve predictability, and materially improve fleet viability. At the same time, under NEIMA, the NRC has “nearly completed” the Part 53 rulemaking to establish a “risk-informed, performance-based and technology-inclusive” licensing framework for advanced reactors, potentially moving those gains from case-by-case execution into a durable regulatory backbone.

Still, even with those gains, Greenwald cautioned that execution now hinges on capacity as much as policy. The speed and scope of reform have placed sustained pressure on federal agencies, particularly the NRC and DOE, as they manage staffing constraints, technical expertise, and institutional continuity. Continued progress, she told lawmakers, will require “maintaining staffing levels at various federal agencies,” preserving the NRC as “a trusted independent regulator,” and ensuring transparency as licensing timelines compress—and that balance will demand steady appropriations, workforce retention, and disciplined coordination across the NRC, DOE, and Department of War. Missed targets, uneven implementation, or erosion of transparency, she said, risk repeating past deployment setbacks that “damaged the industry’s credibility for decades.”

Ultimately, early movers will carry a substantial burden of proof, she suggested. “In recent years, industry, advocates, policymakers, and stakeholders have worked hard to rebuild that credibility through technology and commercial innovation, setting more realistic expectations, implementing federal programs and regulatory reforms, and demonstrating steady progress,” she noted. “Public support for nuclear energy is growing again, but successful early mover projects and maintaining public trust are essential to sustain that momentum.”

A Multi-Pronged Execution Landscape

Perhaps the most elaborate, distinctive factor driving the current momentum for nuclear is the scope of its architecture. Federal policy seems to have essentially opened four lanes at once, each advancing under distinct authorities, financing models, and timelines.

One lane runs through DOE-authorized demonstrations, and it includes programs such as the Reactor Pilot and the ARDP, honing in on first-of-a-kind performance, fuel qualification, and construction sequencing. These projects, however, are being propelled by a compressed schedule (see sidebar: “The July 4 Reactor Pilot Gambit”).

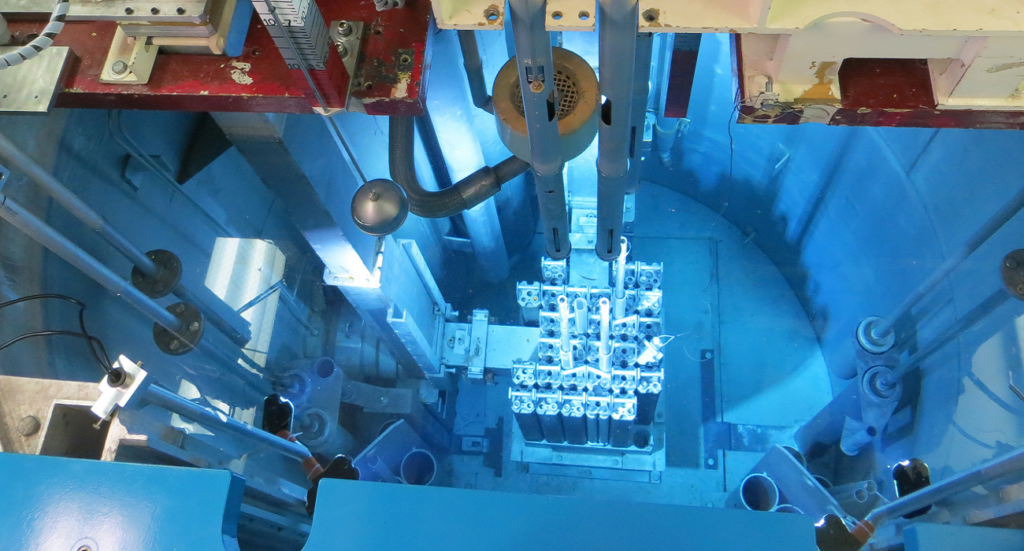

The July 4 Reactor Pilot GambitIn June 2025, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) unveiled an audacious challenge rooted in four Trump administration executive orders signed in May 2025: to demonstrate three reactors achieving criticality by July 4, 2026, the U.S.’s 250th anniversary. Under the DOE Reactor Pilot Program, which operates outside traditional Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) licensing pathways, participating reactors are subject to DOE safety review and NRC technical coordination, but do not require an NRC operational license for demonstration purposes. While sometimes miscast as a regulatory “shortcut,” the DOE’s longstanding authority is limited to federally owned research, test, and fuel‑cycle facilities, and does not bypass the NRC’s role over the commercial fleet. So far, as of January 2026, the 11 projects from 10 companies picked under the DOE’s Reactor Pilot Program have announced notable progress toward criticality. As Idaho National Laboratory (INL) Director John Wagner explained in January Congressional testimony, “When enough fissile material is assembled in the right configuration, it achieves criticality, which is a sustained fission chain reaction”—a foundational physics milestone every reactor must reach to validate its design, safety case, and readiness. “So, it’s a normal progression of the technology testing and demonstration that occurs. It’s sort of an early step in that process.” Energy Secretary Chris Wright tempered expectations in November 2025, saying, “We will have at least one, maybe two, by [the] July 4 date, and others next year, and several others in the following year.” In January, Wagner offered his perspective. “I doubt they will all make it,” he said, referring to the 11 reactors pursuing DOE authorization. “But the thing that’s really exciting is that I do think three can make it and the others will follow quickly thereafter. So, while July 4 is a major milestone, there’s an August and a September and October that will follow, and I think we will see quite a number of these reactors again as their initial demonstration in 2026 that will lead to commercial deployment,” Wagner predicted optimistically. For now, POWER‘s analysis shows that at least seven projects have signed Other Transaction Authority (OTA) agreements with the DOE, while four have broken ground, and three have reached major design milestones within the past 60 days. Antares Nuclear—MARK-0 500-kWth Sodium Heat-Pipe Microreactor | INL. Antares Nuclear cleared a decisive regulatory barrier on Jan. 25, 2026, when the DOE approved its Preliminary Documented Safety Analysis (PDSA), making it the first reactor to receive that approval under the DOE Reactor Pilot Program. Mark-0, which relies on passive sodium heat-pipe thermosyphon circulation, is slated to go live “before July 4,” and will “validate fueling operations, reactor controls, and core physics,” the company said. “This demonstration is a critical step toward generating electricity from advanced microreactors. Mark-0 uses a full-scale core and the same facility and fuel that will support our next reactor test in 2027,” it said. Antares began machining the graphite core on January 12 at its Antares Prime facility, locking in one of the project’s most schedule-sensitive components. The company’s fabrication of high-assay, low-enriched uranium (HALEU) tristructural isotropic (TRISO) fuel began in October, following a DOE allocation in August. While the company closed a $96 million Series B round in December—bringing total capital raised to $130 million—its active contracts with the Department of War and NASA tally to more than $13 million. Final DOE operational authorization is expected within roughly 90 days. If that timeline holds, Antares positions itself as one of the clearest candidates to achieve demonstration-level criticality in 2026, with power ascension testing planned for later this summer or fall. Oklo—Aurora-INL 75-MWe Liquid-Metal Fast Reactor | INL. Oklo broke ground on Sept. 22, 2025, at INL, marking the first private-sector fast-reactor construction at a U.S. national laboratory. Kiewit Nuclear Solutions is serving as the engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) contractor under a master services agreement signed in July 2025. Oklo has secured five metric tons of HALEU fuel down-blended from the Experimental Breeder Reactor-II (EBR-II), the same facility on which Aurora’s design is based. Fuel fabrication will occur at Oklo’s Aurora Fuel Fabrication Facility at INL, which the DOE approved for its Nuclear Safety Design Agreement in November 2025. Oklo began major procurements in 2025, including in-vessel and ex-vessel handling machines, primary and intermediate sodium pumps, and reactor trip systems. The company has mobilized heavy equipment for site earthwork and scheduled controlled blasting and excavation to begin in late 2025 and early 2026. Aurora scales proven sodium-cooled fast-reactor technology demonstrated at EBR-II between 1964 and 1969 to 75 MWe. Oklo is pursuing DOE authorization to accelerate the timeline to initial operations at Aurora INL and will transition to NRC licensing for full commercial deployment. Power ascension is projected in the fourth quarter of 2026. Valar Atomics—Project NOVA/Ward-250 100-kWth High-Temperature Gas-Cooled Reactor | Utah San Rafael Energy Lab. Valar Atomics achieved zero-power criticality on Nov. 17, 2025, at Los Alamos National Laboratory’s National Criticality Experiments Research Center at the Nevada National Security Site. Project Nova is a critical assembly—a zero-power physics experiment, not a power-producing reactor—that used the same graphite, TRISO fuel elements, fuel-to-moderator ratio, B4C control rods, and cladding specifications planned for Ward-250, Valar’s DOE Reactor Pilot Program project, which targets power criticality by July 4, 2026, at Utah’s San Rafael Energy Lab. Over a week-long campaign in November at Project Nova, the company conducted 10 critical configurations and 26 subcritical tests, generating 100 GB of experimental data, including foil activation measurements and external helium-3 detector readings to validate neutronics codes and control rod worth calculations. CEO Isaiah Taylor emphasized that Valar is the first startup to design and build a reactor core from scratch and achieve criticality—distinct from companies that place fuel in existing reactors for irradiation. Project Nova validated Valar’s neutronics predictions before Ward-250 construction. The power plant will follow the same commissioning sequence: cold zero-power critical, hot zero-power critical, then power ascension. Series A funding of $130 million closed in November 2025. Construction broke ground in September 2025, with Kiewit Nuclear Solutions as the EPC contractor. Aalo Atomics—Aalo-X 10-MWe Sodium-Cooled Microreactor | INL. While Aalo completed a major design review on Jan. 22, 2026, that involved DOE and NRC participation, its 40,000-square-foot Austin manufacturing facility is already fabricating reactor modules for on-site assembly at INL, demonstrating factory-built deployment readiness. Construction kicked off at the previously disturbed INL parcel already approved for the canceled Versatile Test Reactor program, accelerating siting approvals (Figure 4).  In 2025, Aalo scaled its team five times, launched a pilot manufacturing factory in Austin, Texas, and completed major DOE milestones including design reviews and the Critical Assembly Facility at INL. “They said you can’t even build a tool shed at the desert site [in] under 2 years,” noted Chief Technology Officer Yasir Arafat. “Well, at Aalo Atomics, we just built the building for our first reactor in 36 days.” Aalo’s vertical basalt-drilling approach and standardized module design seek to reduce construction cost and schedule versus conventional builds. Series B funding ($100 million) provides runway through criticality. CEO Matt Loszak has committed to “founding to fission in less than three years,” with July 4 a stated target. Natura Resources—MSR-1 1-MWth Molten Salt Reactor | Abilene Christian University (ACU), Texas. Natura Resources‘ MSR-1 project at ACU has fully installed its reactor vessel and is awaiting fuel insertion. On Jan. 4, 2026, the DOE allocated FLiBE coolant salt—a lithium fluoride–beryllium fluoride mixture containing 99.99% enriched lithium-7 sourced from Oak Ridge’s historic Molten Salt Reactor Experiment. The DOE separately committed HALEU fuel for the reactor. Detailed engineering is complete and procurement is underway at ACU’s Science and Engineering Research Center. The university holds the NRC research reactor construction permit issued in September 2024, and MSR-1 operates under DOE Authorization for Experiment. Natura’s design builds on proven molten-salt technology from the 1965–1969 Oak Ridge operations with modern safety enhancements. CEO Doug Robison said the salt allocation “ensures we can remain on track to deploy our MSR-1 in 2026.” Power ascension is targeted for the third quarter 2026. The company has secured $120 million in private funding and a $120 million state commitment from Texas. Last Energy—PWR-5 5-MWe Pressurized Water Microreactor | Texas A&M-RELLIS. Last Energy closed Series C funding of more than $100 million in December 2025, allocating about $35 million to complete the PWR-5 pilot at Texas A&M-RELLIS campus. The company procured a full-core load of LEU fuel in December 2025 and secured a land lease at RELLIS. The PWR-5 and commercial PWR-20 share identical physical designs, so pilot testing will directly advance commercialization pathways. Texas A&M and Last Energy signed a collaboration agreement in October 2025. Testing is slated to begin in summer 2026, targeting safe low-power criticality. Separately, Last Energy is advancing a 30-unit data center project in Haskell County, Texas. Radiant Industries—Kaleidos 1-MWe Helium-Cooled Microreactor | INL Demonstration of Microreactor Experiments (DOME) Facility. Radiant is targeting a spring 2026 installation and 60-day operation at INL’s DOME facility. The company secured the first Western commercial HALEU contract with Urenco in September 2025, de-risking fuel supply for commercial production. Series D funding of more than $300 million in December 2025 will bring its total capital above $500 million and accelerate the groundbreaking of the R-50 factory in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, targeting 50 reactors annually by 2030. Heat rejection systems are being tested in California ahead of installation. Founded by former SpaceX engineers, Radiant has demonstrated execution velocity across procurement, regulatory approval, and manufacturing scale-up. It suggests a July 4 criticality is an explicit company target. Terrestrial Energy—Project TETRA/Project TEFLA Integral Molten Salt Reactor (IMSR) Pilot and Fuel Facility | Texas. Terrestrial Energy signed an OTA with the DOE on Jan. 6, 2026, for Project TETRA, a molten salt reactor pilot that runs on standard-assay LEU (<5% U-235), sidestepping the HALEU bottleneck entirely. A parallel OTA for Project TEFLA, signed Jan. 22, covers a fuel fabrication pilot. The commercial IMSR design produces 822 MWth (390 MWe). CEO Simon Irish said the agreement “allows the company to expedite key elements of its program to prepare licensing applications for commercial plant operation.” The siting and construction timelines remain unannounced. Deep Fission—Gravity Reactor 15-MWe Pressurized-Water Reactor, Underground Borehole | Parsons, Kansas. Deep Fission held a groundbreaking on Dec. 9, 2025, at the Great Plains Industrial Park in Parsons, Kansas, a 14,000-acre site formerly used for munitions production. The Gravity reactor sits one mile underground in a 30-inch borehole, where bedrock provides passive shielding and natural containment. The approach eliminates costly above-ground structures, the company says. Deep Fission estimates a 70% to 80% cost reduction compared to conventional plants and a six month timeline from groundbreaking to operation. The design combines established nuclear, oil-and-gas drilling, and geothermal technologies, using standard LEU fuel. Deep Fission targets July 4, 2026, criticality pending DOE authorization. The company, founded in 2023 by father-daughter team Richard and Elizabeth Muller, reported 12.5 GW in letters of intent from potential customers in Kansas, Texas, and Utah. A letter of intent with the Great Plains Development Authority supports future commercial expansion at the same site. Atomic Alchemy—VIPR 15-MWth Light-Water Reactor for Radioisotope Production | Texas. Atomic Alchemy, an Oklo subsidiary, signed an OTA with the DOE on Jan. 7, 2026, for the Versatile Isotope Production Reactor (VIPR), a 15-MWth light-water reactor designed to produce medical and industrial radioisotopes including molybdenum-99 and actinium-225. The facility will irradiate targets for diagnostics, disease treatment, medical research, and national security applications. CEO Jacob DeWitte said the OTA “establishes a framework for execution and risk reduction. By building and operating a pilot reactor, we generate the data and experience to streamline future commercial deployments.” VIPR uses established light-water technology optimized for neutron flux rather than power generation. Atomic Alchemy withdrew its previous NRC construction permit application for the Meitner-1 commercial facility at INL to focus on the pilot. The facility location has not been announced. Atomic Alchemy projects first isotope revenues following pilot operations, positioning VIPR as one of the few DOE pilot projects with near-term commercial revenue potential outside electricity generation. |

The second lane centers on commercial deployment backed by long-term offtake. Utilities and industrial customers are pairing new reactors with committed demand from hyperscalers, manufacturers, and grid operators, and it includes a series of lucrative deals and power purchase agreements (PPAs) that POWER has reported on in detail from companies such as Amazon, Meta, Google, Microsoft, and Dow. These projects serve to anchor financing decisions and pull projects forward from demonstration into scale.

A third lane involves government-led projects, which Wagner described as mission-oriented deployments advancing on a separate track from commercial power—citing the Department of War’s Project Pele (Figure 5) developed by BWX Technologies, DOE-led test reactors such as MARVEL at INL, and the Army’s Project Janus program, which seeks to deploy microreactors at multiple military installations by 2027–2028.

The fourth lane, which involves a resurgence for large reactors, appears to be now coming to the fore. Executive Order 14300 requires at least 10 new large reactors under construction by 2030, and as Wagner noted, “An August 2024 INL analysis identified 65 potential sites across the U.S., finding that 18 sites are particularly promising for near-term AP1000 deployment, with an additional 29 sites having strong potential.” While no projects have broken ground, in October 2025, Westinghouse owners Brookfield and Cameco announced an $80 billion agreement with the U.S. government centered on large reactor deployment using Westinghouse reactors, though no details have yet been disclosed.

Westinghouse has suggested it is fielding a substantial pipeline, including efforts to restart construction at the V.C. Summer site in South Carolina (where Brookfield has partnered with Santee Cooper), as well as proposals by Fermi America to build four AP1000 units in Texas. Other potential projects include sites that already hold NRC early site permits, including Clinton in Illinois, Grand Gulf in Mississippi, North Anna in Virginia, Vogtle in Georgia, PSEG’s Salem-Hope Creek site in New Jersey, TVA’s Clinch River site in Tennessee, and Turkey Point Units 6 and 7 in Florida, where the NRC has authorized construction but no work has begun.

“We are past what we call the first-of-a-kind stage,” said James Wyble III, Westinghouse’s vice president of AP1000 project development, who emphasized that the AP1000’s design is complete, supply bottlenecks are mapped, and the company now views the challenge as moving rapidly into “next-of-a-kind and Nth-of-a-kind” construction by reinvigorating domestic manufacturing, labor, and long-lead procurement.

Still, John Williams of Southern Nuclear Operating Company, drawing directly on Southern’s experience completing Vogtle Units 3 and 4, cautioned that despite AP1000 design maturity, new large reactors remain constrained by high upfront capital costs, exposure to construction “tail risk,” balance-sheet and credit pressures on sponsors, and an underdeveloped domestic supply chain. “The construction of Vogtle Units 3 and 4 is a textbook example of how these kinds of events, over which the developer has no control, can cause disruption, impede progress, and raise costs,” Williams recently told lawmakers, arguing that targeted federal risk mitigation is necessary to bridge the gap from early projects to true “Nth-of-a-kind” deployment. Some specific policy mechanisms that could serve as evidence-based solutions include enhanced investment tax credits for early projects, federal cost-sharing to address construction tail risk, and reforms to tax-credit transferability to improve cash flow during construction, he suggested.

The Supply Chain Bottleneck: Five Constraints on First Movers

As several first movers told POWER, however, the biggest challenge that lays ahead is rooted less in policy ambition and more in the physical realities of fuel supply, manufacturing capacity, and labor availability. Gaps, they suggested, persist across multiple, interdependent layers.

HALEU Enrichment Remains an Immediate Choke Point. Many advanced reactor designs require HALEU, fuel material enriched up to 19.75% U-235, compared with roughly 5% for today’s operating fleet. But, “Currently, no commercial-scale HALEU production exists in the U.S.,” Wagner noted. While Centrus Energy’s Ohio demonstration facility began limited HALEU production in October 2023—producing roughly 900 kilograms by mid-2025—and INL can supply small quantities from existing inventories for fuel qualification and testing, neither pathway supports sustained commercial deployment. So far, the DOE’s January 2026 award of $2.7 billion to enrichment projects under the HALEU Availability Program marked progress, but deconversion capacity—a step required to turn enriched uranium into reactor-ready fuel—has yet to be awarded.

Advanced Fuel Fabrication Is an Emerging Constraint. Beyond enrichment, several advanced reactor designs depend on specialty fuels that are significantly more complex to manufacture than conventional fuel assemblies. High-temperature gas-cooled reactors and some microreactors require TRISO fuel—uranium kernels encased in multiple ceramic and carbon layers designed to retain fission products under extreme conditions. While DOE-supported production has allowed limited quantities for defense and demonstration projects, including early fuel for Department of War programs, experts note that current fabrication capacity is insufficient to support scaled commercial deployment. Even where enrichment pathways exist, fuel qualification, throughput, and quality assurance remain gating steps that must expand in parallel with reactor construction schedules.

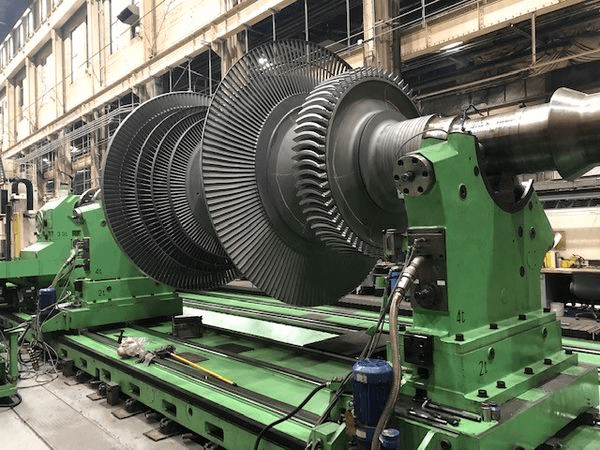

Large-Component Manufacturing Presents a Parallel Constraint. Another key consideration is that reactor pressure vessels, steam generators, and other nuclear-grade forgings require specialized capabilities that the U.S. largely lost during decades of inactivity. Wagner warned that domestic production of long-lead components “remains insufficient to meet expected demand,” forcing developers to rely on overseas suppliers. Southern Nuclear’s Williams noted that although Vogtle Units 3 and 4 retired major technology and licensing risks, the lag in follow-on projects has already led to some atrophy in the workforce and supply chain advances achieved during construction. Today, notably, nuclear-grade forgings are sourced primarily from Japan, South Korea, and France, and industry estimates suggest rebuilding certified domestic capacity could require five to seven years—and a sustained multi-unit order book—to justify the capital investment.

Workforce Availability Compounds Both Challenges. Finally, several experts have pointed out to POWER that deploying new nuclear capacity at the scale envisioned will require tens of thousands of additional engineers, licensed operators, technicians, and craft workers. The bottleneck appears most acute in nuclear-qualified trades. While Vogtle alone employed roughly 9,000 craft workers at peak construction, the simultaneous builds of multiple large reactors would require multiples of that workforce. Without a visible, continuous pipeline of projects, experts caution that training capacity, credentialing, and labor retention remain fragile.

“Rebuilding and scaling these supply chains takes time and sustained investment,” noted Korsnick. “Clear demand signals, execution certainty, and federal support can help manufacturers make the investments needed to deliver components reliably and at scale.” For now, continued coordination among Congress, the Trump administration, states, educational institutions, labor, and industry could help the U.S. ensure it has the people, capabilities, and industrial capacity needed to deliver nuclear energy over the long term.

- Aalo Atomics

- Abilene Christian University

- advanced reactors

- Amazon

- ASP Isotopes

- Atomic Alchemy

- Bechtel

- Brookfield

- BWX Technologies

- Cameco

- Centrica

- Centrus Energy

- Deep Fission

- Defense Innovation Unit

- DOE nuclear programs

- Dow

- Fermi America

- Framatome

- GE Vernova Hitachi

- Global Nuclear Fuel

- HALEU

- HD Hyundai

- Holtec Government Services

- Idaho National Laboratory

- Kairos Power

- Kiewit Nuclear Solutions

- Last Energy

- Long Mott Energy

- Los Alamos National Laboratory

- Meta

- microreactors

- Microsoft

- NASA

- Natura Resources

- nuclear construction

- nuclear demonstration projects

- Nuclear Energy Institute

- Nuclear Innovation Alliance

- nuclear licensing

- Nuclear Supply Chain

- NuScale

- Oak Ridge National Laboratory

- Oklo

- PSEG

- Radiant Industries

- Santee Cooper

- small modular reactors

- Southern Nuclear Operating Company

- Tennessee Valley Authority

- TerraPower

- Terrestrial Energy

- Texas A&M

- URENCO

- Valar Atomics

- Westinghouse

- x-energy